Refine search

Actions for selected content:

106116 results in Materials Science

MRS MOVERS & SHAKERS: Spread the good news!

-

- Journal:

- MRS Bulletin / Volume 45 / Issue 1 / January 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 January 2020, p. 72

- Print publication:

- January 2020

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Reliability implications of partial shading on CIGS photovoltaic devices: A literature review

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 24 / 30 December 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 30 December 2019, pp. 3977-3987

- Print publication:

- 30 December 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

JMR volume 34 issue 24 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 24 / 30 December 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 30 December 2019, pp. f1-f5

- Print publication:

- 30 December 2019

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

JMR volume 34 issue 24 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 24 / 30 December 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 30 December 2019, pp. b1-b7

- Print publication:

- 30 December 2019

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

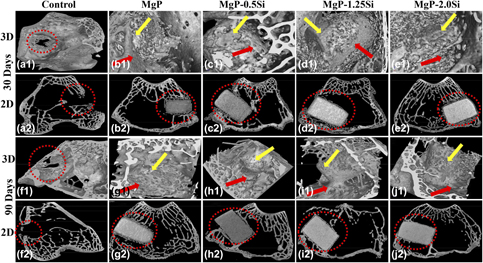

Quantitative assessment of degradation, cytocompatibility, and in vivo bone regeneration of silicon-incorporated magnesium phosphate bioceramics

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 24 / 30 December 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 30 December 2019, pp. 4024-4036

- Print publication:

- 30 December 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

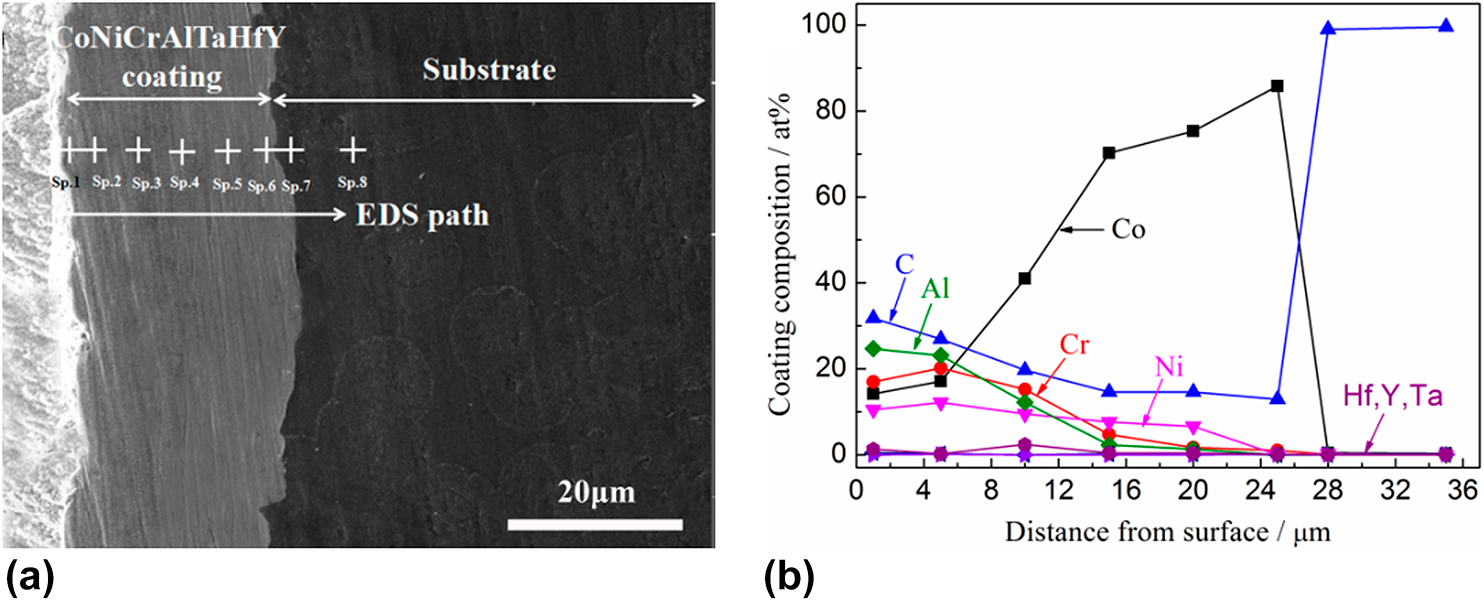

Improved oxidation resistance of CoNiCrAlTaHfY/Co coating on C/C composites by vapor phase surface alloying

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 35 / Issue 5 / 16 March 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 December 2019, pp. 500-507

- Print publication:

- 16 March 2020

-

- Article

- Export citation

Planet–satellite nanostructures from inorganic nanoparticles: from synthesis to emerging applications

-

- Journal:

- MRS Communications / Volume 10 / Issue 1 / March 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 December 2019, pp. 112-122

- Print publication:

- March 2020

-

- Article

- Export citation

A perspective on overcoming water-related stability challenges in molecular and hybrid semiconductors

-

- Journal:

- MRS Communications / Volume 10 / Issue 1 / March 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 December 2019, pp. 98-111

- Print publication:

- March 2020

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Enhanced light-matter interactions in size tunable graphene–gold nanomesh

-

- Journal:

- MRS Communications / Volume 10 / Issue 1 / March 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 December 2019, pp. 135-140

- Print publication:

- March 2020

-

- Article

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp 519-572

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Imaging Physics

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp 71-198

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Radiation Damage and Cryo Microscopy

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp 457-495

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp 573-579

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Applications, and Future Prospects

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp 496-514

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Foreword

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp xiii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp v-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - X-Ray Microscope Systems

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp 241-258

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - X-Ray Microscope Instrumentation

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp 259-320

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - A Bit of History

-

- Book:

- X-ray Microscopy

- Published online:

- 28 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2019, pp 5-22

-

- Chapter

- Export citation