Refine search

Actions for selected content:

106116 results in Materials Science

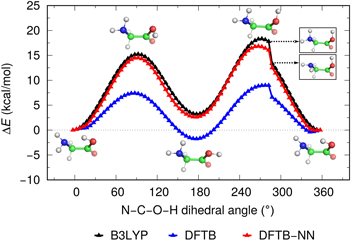

Artificial neural network correction for density-functional tight-binding molecular dynamics simulations

-

- Journal:

- MRS Communications / Volume 9 / Issue 3 / September 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2019, pp. 867-873

- Print publication:

- September 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

JMR volume 34 issue 12 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 12 / 28 June 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2019, pp. f1-f5

- Print publication:

- 28 June 2019

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Laser-induced structure transition of diamond-like carbon coated on cemented carbide and formation of reduced graphene oxide

-

- Journal:

- MRS Communications / Volume 9 / Issue 3 / September 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2019, pp. 910-915

- Print publication:

- September 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

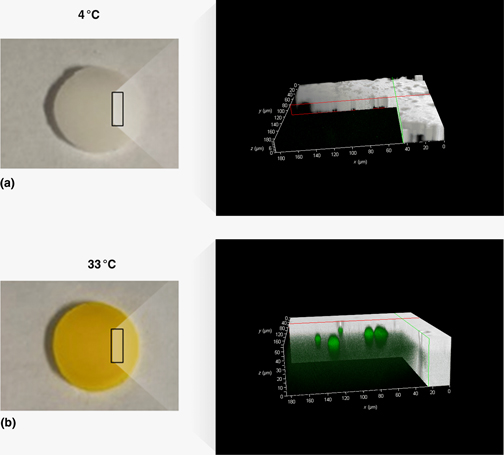

Loading and release of a model high-molecular-weight protein from temperature-sensitive micro-structured hydrogels

-

- Journal:

- MRS Communications / Volume 9 / Issue 3 / September 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2019, pp. 1041-1045

- Print publication:

- September 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

JMR volume 34 issue 12 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 12 / 28 June 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2019, pp. b1-b5

- Print publication:

- 28 June 2019

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Effect of Gd3+ doping on structural, morphological, optical, dielectric, and nonlinear optical properties of high-quality PbI2 thin films for optoelectronic applications

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 16 / 28 August 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2019, pp. 2765-2774

- Print publication:

- 28 August 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

Powder X-ray structural studies and reference diffraction patterns for three forms of porous aluminum terephthalate, MIL-53(A1)

-

- Journal:

- Powder Diffraction / Volume 34 / Issue 3 / September 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 June 2019, pp. 216-226

-

- Article

- Export citation

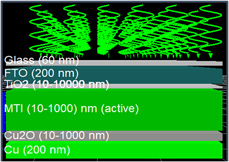

Simulation studies of Sn-based perovskites with Cu back-contact for non-toxic and non-corrosive devices

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 16 / 28 August 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 June 2019, pp. 2789-2795

- Print publication:

- 28 August 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

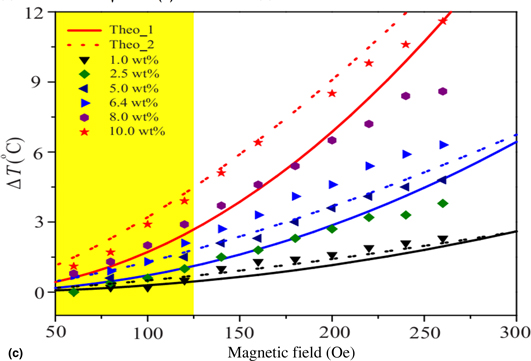

Role of nanoparticle interaction in magnetic heating

-

- Journal:

- MRS Communications / Volume 9 / Issue 3 / September 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 June 2019, pp. 1034-1040

- Print publication:

- September 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

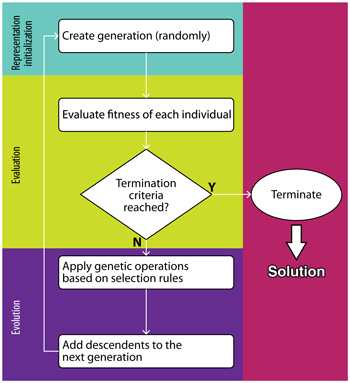

Symbolic regression in materials science

-

- Journal:

- MRS Communications / Volume 9 / Issue 3 / September 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 June 2019, pp. 793-805

- Print publication:

- September 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Molecular Modeling Applications in Crystallization

-

-

- Book:

- Handbook of Industrial Crystallization

- Published online:

- 14 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2019, pp 136-171

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Melt Crystallization

-

-

- Book:

- Handbook of Industrial Crystallization

- Published online:

- 14 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2019, pp 266-289

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Corn stover–derived biochar for efficient adsorption of oxytetracycline from wastewater

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 17 / 16 September 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 June 2019, pp. 3050-3060

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

Chapter 14 - Crystallization of Proteins

-

-

- Book:

- Handbook of Industrial Crystallization

- Published online:

- 14 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2019, pp 414-459

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Crystal Nucleation

-

-

- Book:

- Handbook of Industrial Crystallization

- Published online:

- 14 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2019, pp 76-114

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Crystallizer Mixing

-

-

- Book:

- Handbook of Industrial Crystallization

- Published online:

- 14 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2019, pp 290-312

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A novel and facile way to synthesize diamondoids nanowire cluster array

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Materials Research / Volume 34 / Issue 17 / 16 September 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 June 2019, pp. 2976-2982

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2019

-

- Article

- Export citation

Chapter 15 - Crystallization in Foods

-

-

- Book:

- Handbook of Industrial Crystallization

- Published online:

- 14 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2019, pp 460-478

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Solutions and Solution Properties

-

-

- Book:

- Handbook of Industrial Crystallization

- Published online:

- 14 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2019, pp 1-31

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Handbook of Industrial Crystallization

- Published online:

- 14 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2019, pp v-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation