3356294 results

Leaving the Fight

- Surrender, Prisoners of War, and Detainees in Western Warfare

-

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 February 2025

Middle Eastern and European Christianity, 16th-20th Century

- Connected Histories

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2023

East Asian Film Remakes

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 July 2023

State Atrophy in Syria

- War, Society and Institutional Change

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023

The Eye of the Cinematograph

- Lévinas and Realisms of the Body

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 February 2023

Medieval Syria and the Onset of the Crusades

- The Political World of Bilad al-Sham 1050-1128

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 June 2023

The Apocalypse of the Birds

- 1 Enoch and the Jewish Revolt against Rome

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 July 2023

Modernism, Material Culture and the First World War

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2023

Revolutionaries and Global Politics

- War Machines from the Bolsheviks to ISIS

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 February 2023

Modern Philosopher Kings

- Wisdom and Power in Politics

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2023

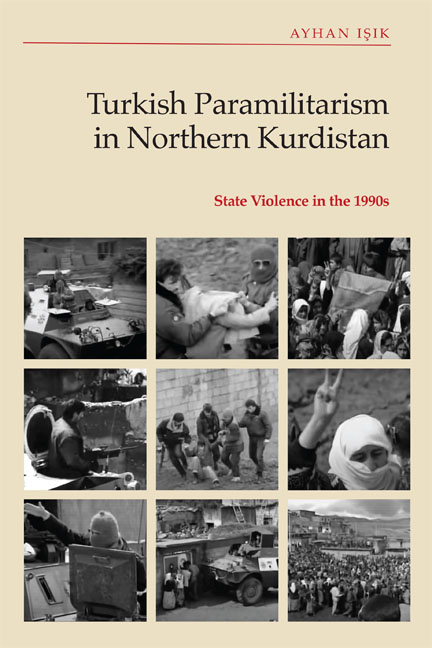

Turkish Paramilitarism in Northern Kurdistan

- State Violence in the 1990s

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 January 2024

Silicon Valley Cinema

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 June 2023

Dominance Through Division

- Group-Based Clientelism in Japan

-

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 March 2025

Invisible Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Literature

- Rethinking Urban Modernity

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 January 2024

Performance, Theatricality and the US Presidency

- The Currency of Distrust

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 May 2023

On Performance and Disability: Differentiated Bodies and the Aesthetics of Invasion

-

- Journal:

- TDR: The Drama Review / Volume 69 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 March 2025, pp. 86-111

- Print publication:

- March 2025

-

- Article

- Export citation

ICE volume 46 issue 3 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology / Volume 46 / Issue 3 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 March 2025, pp. f1-f8

- Print publication:

- March 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Rethinking Bach Bettina Varwig, ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022 pp. xiv + 408, ISBN 978 0 190 94389 9

-

- Journal:

- Eighteenth-Century Music / Volume 22 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 March 2025, pp. 125-127

- Print publication:

- March 2025

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Debt Crisis of the 1980s: Law and Political Economy. By Jérôme Sgard. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023. Pp. 354. $165.00, hardcover.

-

- Journal:

- The Journal of Economic History / Volume 85 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 March 2025, pp. 299-302

- Print publication:

- March 2025

-

- Article

- Export citation

Notes on a Scattered Subject in Montmartre: The Self-Portrait of Susan Marie Ossman

-

- Journal:

- TDR: The Drama Review / Volume 69 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 March 2025, pp. 21-35

- Print publication:

- March 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation