Refine search

Actions for selected content:

25562 results in Classical literature

Chapter 2 - Sappho and Sedgwick as Reparative Readers

- from Part I - Reparative Reading

-

- Book:

- Sappho and Homer

- Published online:

- 07 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023, pp 35-56

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Reparative Intertextualities

- from Part I - Reparative Reading

-

- Book:

- Sappho and Homer

- Published online:

- 07 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023, pp 19-34

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Sapphic Remembering, Lyric Kleos

- from Part II - Sappho and Homer

-

- Book:

- Sappho and Homer

- Published online:

- 07 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023, pp 175-192

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

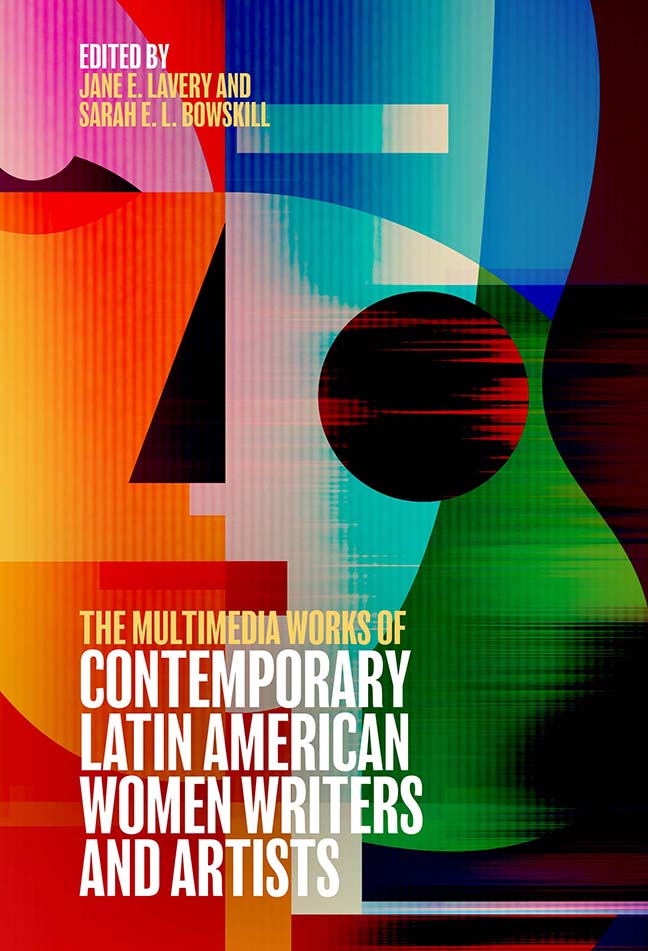

The Multimedia Works of Contemporary Latin American Women Writers and Artists

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 17 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 29 August 2023

Conclusion: Assembling the Future

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 234-251

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: Looking and Looking Back

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 1-35

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Interlude: Colonial Visions

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 171-198

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Blindness and Spectatorship

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 199-233

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Blindness as Metaphorical Death

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 109-132

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Blindness and / as Punishment

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 75-108

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Blindness as Second Sight

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 133-170

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements (Situating Knowledges)

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp xii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp xi-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 252-292

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Towards Visual Activism

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 36-74

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp vi-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 293-295

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp ix-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes on the Text

-

- Book:

- Blindness and Spectatorship in Ancient and Modern Theatres

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp xv-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation