3356294 results

State violence against migrant women: Ontological security, threat, and legitimacy

-

- Journal:

- Review of International Studies , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-17

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Taking Account of Blackness Among Latinos: Afro-Latino Oversample

-

- Journal:

- PS: Political Science & Politics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 6-8

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-15

-

- Article

- Export citation

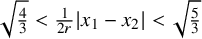

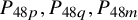

Isometric dilation and Sarason’s commutant lifting theorem in several variables

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Canadian Journal of Mathematics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-33

-

- Article

- Export citation

Modeling phase noise estimation in air borne pulse Doppler RF sensor using range correlation and inline flicker

-

- Journal:

- International Journal of Microwave and Wireless Technologies , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-15

-

- Article

- Export citation

Causal Effect Between Natural Hair Color and Endometriosis in a European Population: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization

-

- Journal:

- Twin Research and Human Genetics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-11

-

- Article

- Export citation

Surveying Native Americans: Early Lessons from the CMPS

-

- Journal:

- PS: Political Science & Politics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 10-14

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Elastic textile-based wearable modulation of musculoskeletal load: A comprehensive review of passive exosuits and resistance clothing

-

- Journal:

- Wearable Technologies / Volume 6 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, e11

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Design and evaluation of AE4W: An active and flexible shaft-driven shoulder exoskeleton for workers

-

- Journal:

- Wearable Technologies / Volume 6 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, e12

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

POLYNOMIALS REPRESENTED BY NORM FORMS VIA THE BETA SIEVE

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Institute of Mathematics of Jussieu , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-57

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Adoption of Paid Sick Leave in US States

-

- Journal:

- State Politics & Policy Quarterly ,

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-22

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Popular music studies behind the Iron Curtain: the constitution of popular music research in East-Central Europe before 1989

-

- Journal:

- Popular Music , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-34

-

- Article

- Export citation

Anticipating Office: Does the Populist Radical Right Decrease Its Populist Communication When It Has the Opportunity to Join Government?

-

- Journal:

- Government and Opposition , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-24

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Sphere packings in Euclidean space with forbidden distances

-

- Journal:

- Forum of Mathematics, Sigma / Volume 13 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, e49

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Toward a Qualitative Study of the American Voter

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-17

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Politics of Police Reform in the States

-

- Journal:

- State Politics & Policy Quarterly ,

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-19

-

- Article

- Export citation

International Management Behavior

- Global and Sustainable Leadership

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- February 2025

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2025

-

- Textbook

- Export citation

Covert contraceptive use among women with a previous unintended pregnancy in Nigeria: A multilevel investigation of individual- and contextual-level factors

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Biosocial Science , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-18

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Prison before the Panopticon: Incarceration in Ancient and Modern Political Philosophy. By Jacob Abolafia. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2024. 256p.

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 February 2025, pp. 1-2

-

- Article

- Export citation