Refine listing

Actions for selected content:

15726 results in ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- Contentious Belonging

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 06 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 27 May 2019, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - ‘Normalising’ the Orang Rimba: Between Mainstreaming, Marginalising and Respecting Indigenous Culture

- from PART 4 - RELIGION AND ETHNICITY

-

-

- Book:

- Contentious Belonging

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 06 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 27 May 2019, pp 232-252

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

PART 4 - RELIGION AND ETHNICITY

-

- Book:

- Contentious Belonging

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 06 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 27 May 2019, pp 153-154

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Indonesia Update Series

-

- Book:

- Contentious Belonging

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 06 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 27 May 2019, pp 281-282

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

After the Coup

- The National Council for Peace and Order Era and the Future of Thailand

-

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 23 May 2019

- Print publication:

- 07 January 2019

The Elderly Must Endure

- Ageing in the Minangkabau Community in Modern Indonesia

-

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 16 May 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2018

The Indonesian Economy in Transition

- Policy Challenges in the Jokowi Era and Beyond

-

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 16 May 2019

- Print publication:

- 06 March 2019

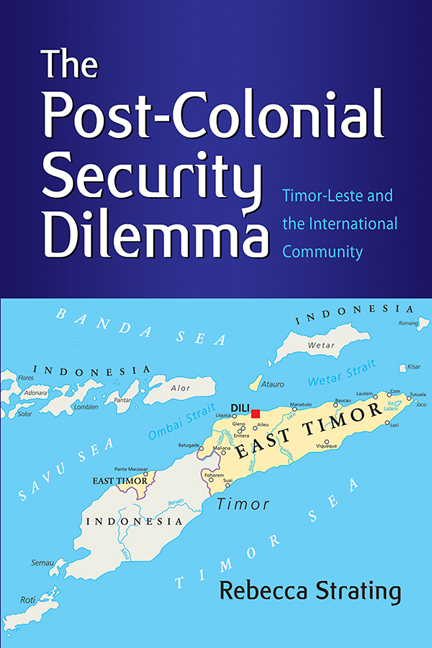

The Post-Colonial Security Dilemma

- Timor-Leste and the International Community

-

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 16 May 2019

- Print publication:

- 20 November 2018

Part I - Structural Constraints and Opportunities

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 57-58

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction: Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition

-

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 1-56

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

18 - The Tea Shop Meets the 8 O'clock News: Facebook, Convergence and Online Public Spaces

- from Part IV - Society and Media

-

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 327-365

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Covering Rakhine: Journalism, Conflict and Identity

- from Part II - Journalism in Transition

-

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 229-238

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Burma or Myanmar? A Note on Terminology

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp xvii-xx

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 395-407

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - The Metamorphosis of Media in Myanmar's Ethnic States

- from Part II - Journalism in Transition

-

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 210-228

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - New Video Generation: The Myanmar Motion Picture Industry in 2017

- from Part III - Creative Expression

-

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 287-306

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Precarity and Risk in Myanmar's Media: A Longitudinal Analysis of Natural Disaster Coverage by The Irrawaddy

- from Part II - Journalism in Transition

-

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 177-200

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp v-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Journalism in Transition

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 149-150

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - Creative Expression

-

- Book:

- Myanmar Media in Transition

- Published by:

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Published online:

- 07 September 2019

- Print publication:

- 13 May 2019, pp 265-266

-

- Chapter

- Export citation