Refine search

Actions for selected content:

26207 results in Theoretical Physics and Mathematical Physics

11 - The Path Integral

-

- Book:

- Quantum Mechanics

- Published online:

- 14 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 December 2022, pp 268-298

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - Why Quantum Mechanics?

-

- Book:

- Quantum Mechanics

- Published online:

- 14 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 December 2022, pp 337-344

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Axioms of Quantum Mechanics and their Consequences

-

- Book:

- Quantum Mechanics

- Published online:

- 14 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 December 2022, pp 58-88

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

C - Further Reading

-

- Book:

- Quantum Mechanics

- Published online:

- 14 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 December 2022, pp 354-355

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - The Hydrogen Atom

-

- Book:

- Quantum Mechanics

- Published online:

- 14 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 December 2022, pp 201-240

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Finite quasisimple groups acting on rationally connected threefolds

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society / Volume 174 / Issue 3 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 December 2022, pp. 531-568

- Print publication:

- May 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

Pseudo-holomorphic dynamics in the restricted three-body problem

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society / Volume 174 / Issue 3 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 December 2022, pp. 663-693

- Print publication:

- May 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

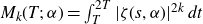

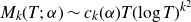

Moments of the Hurwitz zeta function on the critical line

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society / Volume 174 / Issue 3 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 November 2022, pp. 631-661

- Print publication:

- May 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

Most numbers are not normal

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society / Volume 175 / Issue 1 / July 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 November 2022, pp. 1-11

- Print publication:

- July 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Fillability of small Seifert fibered spaces

-

- Journal:

- Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society / Volume 174 / Issue 3 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 November 2022, pp. 585-604

- Print publication:

- May 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

Continuous Groups for Physicists

-

- Published online:

- 24 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 05 January 2023

15 - Applications to Galaxies

- from Part III - Applications

-

- Book:

- Noether Symmetries in Theories of Gravity

- Published online:

- 10 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 November 2022, pp 294-309

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

18 - Strings, Swampland, Renormalizability, and Viability

- from Part III - Applications

-

- Book:

- Noether Symmetries in Theories of Gravity

- Published online:

- 10 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 November 2022, pp 351-375

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Extensions with Higher Derivatives of R and T

- from Part II - The Noether Symmetry Approach

-

- Book:

- Noether Symmetries in Theories of Gravity

- Published online:

- 10 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 November 2022, pp 165-173

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- Noether Symmetries in Theories of Gravity

- Published online:

- 10 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 November 2022, pp 398-423

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

16 - Applications to Cosmology

- from Part III - Applications

-

- Book:

- Noether Symmetries in Theories of Gravity

- Published online:

- 10 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 November 2022, pp 310-333

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notation

-

- Book:

- Noether Symmetries in Theories of Gravity

- Published online:

- 10 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 November 2022, pp xxii-xxiii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Two Noether Theorems

- from Part I - Preliminaries

-

- Book:

- Noether Symmetries in Theories of Gravity

- Published online:

- 10 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 November 2022, pp 16-33

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - The Noether Symmetry Approach

-

- Book:

- Noether Symmetries in Theories of Gravity

- Published online:

- 10 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 November 2022, pp 105-106

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Toward Quantum Gravity

- from Part I - Preliminaries

-

- Book:

- Noether Symmetries in Theories of Gravity

- Published online:

- 10 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 November 2022, pp 88-105

-

- Chapter

- Export citation