Refine search

Actions for selected content:

35446 results in Ecology and conservation

5 - Fish Consumption and Provisioning

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Sea Fisheries, 1400-1600

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 22 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2023, pp 194-222

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Sea Fisheries, 1400-1600

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 22 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2023, pp 266-293

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Diversity and Cooperation in Sixteenth-Century Fisheries

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Sea Fisheries, 1400-1600

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 22 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2023, pp 47-88

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendices

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Sea Fisheries, 1400-1600

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 22 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2023, pp 255-265

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Sea Fisheries, 1400-1600

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 22 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2023, pp xii-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Remnant Rhine delta population of Great Reed Warblers maintains high diversity in migration timing, stopping sites, and winter destinations

-

- Journal:

- Bird Conservation International / Volume 33 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 December 2023, e77

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Evaluation of the limiting factors affecting the Seychelles Kestrel Falco araeus on Praslin Island (Seychelles) and considerations regarding a possible reintroduction of the species

-

- Journal:

- Bird Conservation International / Volume 33 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 December 2023, e79

-

- Article

- Export citation

An updated checklist of Stomiiformes from Indian waters with nine new records

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom / Volume 103 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 December 2023, e95

-

- Article

- Export citation

Latitudinal shift of the associated hosts in Sagamiscintilla thalassemicola (Galeommatoidea: Galeommatidae), a rare ectosymbiotic bivalve that lives on the proboscis of echiuran worms

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom / Volume 103 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 December 2023, e94

-

- Article

- Export citation

Logbooks and Antarctic sealing. Approaching early- and late-19th-century exploitation strategies and their archaeological footprint

-

- Journal:

- Polar Record / Volume 59 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 December 2023, e39

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Thomas Blanky (1804–1848/51?)

-

- Journal:

- Polar Record / Volume 59 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 December 2023, e38

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

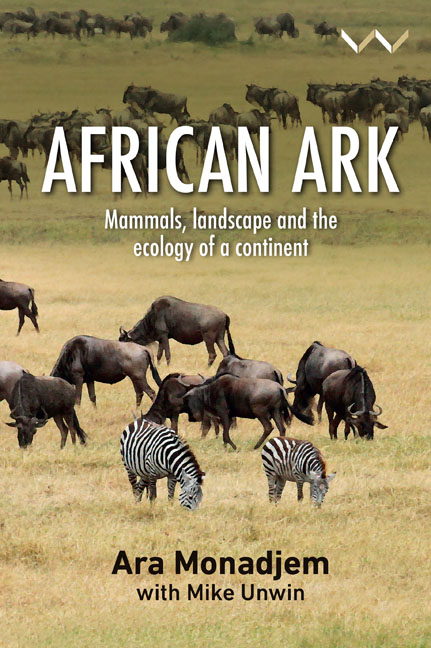

African Ark

- Mammals, Landscape and the Ecology of a Continent

-

- Published by:

- Wits University Press

- Published online:

- 29 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 February 2023

Thamnolecania yunusii (Ramalinaceae) – A new species of lichenised fungus from Horseshoe Island (Antarctic Peninsula)

-

- Journal:

- Polar Record / Volume 59 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 November 2023, e37

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The first validated record of Epinephelus areolatus (Forsskål, 1775) (Perciformes: Serranidae) from Syrian marine waters

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom / Volume 103 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 November 2023, e93

-

- Article

- Export citation

Impact of historic sediment characterisation on predicting polychaete distributions: a case study of so-called muddy habitat shovelhead worms (Annelida: Magelonidae)

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom / Volume 103 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 November 2023, e92

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

3 - Taxonomic Status of the African Buffalo

- from Part I - Conservation

-

-

- Book:

- Ecology and Management of the African Buffalo

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 49-65

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

12 - African Buffalo and Colonial Cattle: Is ‘Systems Change’ the Best Future for Farming and Nature in Africa?

- from Part III - Diseases

-

-

- Book:

- Ecology and Management of the African Buffalo

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 320-350

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

14 - Management Aspects of the Captive-Bred African Buffalo (Syncerus caffer) in South Africa

- from Part IV - Management

-

-

- Book:

- Ecology and Management of the African Buffalo

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 382-406

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

9 - Infections and Parasites of Free-Ranging African Buffalo

- from Part III - Diseases

-

-

- Book:

- Ecology and Management of the African Buffalo

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 239-268

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

2 - The Evolutionary History of the African Buffalo: Is It Truly a Bovine?

- from Part I - Conservation

-

-

- Book:

- Ecology and Management of the African Buffalo

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 25-48

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation