Refine search

Actions for selected content:

5316 results in Phonetics and phonology

Glossary

-

- Book:

- Stress and Accent

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp 315-318

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- Stress and Accent

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp 319-349

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Stress and Accent

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Summary and Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Stress and Accent

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp 297-310

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Stress and Accent

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Stress and Accent

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp 350-354

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- Stress and Accent

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Typology

-

- Book:

- Stress and Accent

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp 66-110

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Correspondence: Map and Match

-

- Book:

- Stress and Accent

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp 111-150

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Second Language Phonology

- Phonetic Variation and Phonological Representations

-

- Published online:

- 20 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025

-

- Element

- Export citation

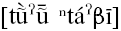

Uzbek

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Phonetic Association / Volume 55 / Issue 1-2 / August 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 March 2025, pp. 152-168

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Stress and Accent

-

- Published online:

- 15 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025

Issues in Metrical Phonology

- Insights from Ukrainian

-

- Published online:

- 28 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2025

-

- Element

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

IPA volume 54 issue 2 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Phonetic Association / Volume 54 / Issue 2 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2025, pp. b1-b2

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

San Martín Peras Mixtec

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Phonetic Association / Volume 54 / Issue 2 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2025, pp. 811-852

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Sasak, Meno-Mené dialect – ADDENDUM

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Phonetic Association / Volume 54 / Issue 2 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2025, p. 883

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

San Juan Piñas Mixtec

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Phonetic Association / Volume 54 / Issue 2 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2025, pp. 853-882

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

IPA volume 54 issue 2 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Phonetic Association / Volume 54 / Issue 2 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2025, pp. f1-f2

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Zhongjiang Chinese

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Phonetic Association / Volume 54 / Issue 3 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 February 2025, pp. 1071-1099

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

How tight is the link between alternations and phonotactics?

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

or

or  ) is an Otomanguean language spoken by roughly 11,500 people in the municipality of San Martín Peras, in Oaxaca, Mexico (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2020), as shown in Figure 1. The municipality is in the district of Juxtlahuaca, bordering the state of Guerrero. As of 2020, approximately 97% of the population of the municipality over three years old is a speaker of an Indigenous language. Of those that speak an Indigenous language, approximately 60% also speak Spanish, meaning that around 37% of the total population is monolingual in Mixtec (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2020). Despite these figures, it is difficult to estimate the total number of native speakers of the language, as many community members have migrated to other parts of Mexico and the United States, especially to several towns in California (Mendoza, 2020).

) is an Otomanguean language spoken by roughly 11,500 people in the municipality of San Martín Peras, in Oaxaca, Mexico (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2020), as shown in Figure 1. The municipality is in the district of Juxtlahuaca, bordering the state of Guerrero. As of 2020, approximately 97% of the population of the municipality over three years old is a speaker of an Indigenous language. Of those that speak an Indigenous language, approximately 60% also speak Spanish, meaning that around 37% of the total population is monolingual in Mixtec (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2020). Despite these figures, it is difficult to estimate the total number of native speakers of the language, as many community members have migrated to other parts of Mexico and the United States, especially to several towns in California (Mendoza, 2020).