Refine search

Actions for selected content:

2006 results in Discourse analysis

Figures

-

- Book:

- Understanding the Language of Virtual Interaction

- Published online:

- 05 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 25 September 2025, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

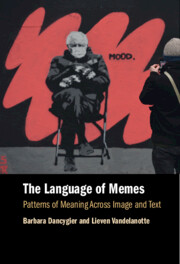

The Language of Memes

- Patterns of Meaning Across Image and Text

-

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025

2 - Memes and Multimodal Figuration

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 11-25

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp xvii-xviii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp xiv-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tables

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp xiii-xiii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Memetic Form and Memetic Meaning

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 151-170

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Memetic Use of Personal Pronouns

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 90-110

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Memetic Discourse on Social Media Platforms

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 171-201

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp x-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Embedding Discourse Spaces without Say Verbs

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 131-150

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - One Does Not Simply Draw a Conclusion

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 217-233

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Labelling Memes

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 43-67

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp vii-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Say, Tell, and Be Like Meme Constructions

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 111-130

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 234-242

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Memes and Advertising

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 202-216

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Image Macro Memes

-

- Book:

- The Language of Memes

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 26-42

-

- Chapter

- Export citation