Refine search

Actions for selected content:

25562 results in Classical literature

5 - Places: Black Consciousness Ecologies of Futurity

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp 147-172

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp ix-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

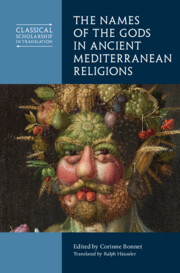

The Names of the Gods in Ancient Mediterranean Religions

-

- Published online:

- 23 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 March 2024

Chapter 4 - Motion Images in Ecphrases

- from III - Complex Cinematism

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 123-155

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 467-523

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - Arrow and Axes in the Odyssey; or, The Case of the Insoluble Enigma

- from IV - The Cinema Imagines Difficult Texts

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 377-429

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Fade-In

- from I - Prolegomena

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 3-24

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - The Face of Tragedy: Mask and Close-Up

- from III - Complex Cinematism

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 295-344

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

II - Progymnasmata: Ways of Seeing

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 25-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - The Cinematic Nature of the Opening Scene in Heliodorus’ An Ethiopian Story

- from III - Complex Cinematism

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 267-294

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Static Flight: Zeno’s Arrow and Cinematographic Motion

- from III - Complex Cinematism

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 215-232

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 524-530

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 13 - Fade-Out

- from V - Epilegomena

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 459-466

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Douris’ Jason: Reckless Interpretations and the Ongoing Moment

- from II - Progymnasmata: Ways of Seeing

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 27-71

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Illustrations

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp x-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

IV - The Cinema Imagines Difficult Texts

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 345-456

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp xv-xxii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

I - Prolegomena

-

- Book:

- Classical Antiquity and the Cinematic Imagination

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 1-24

-

- Chapter

- Export citation