8.1 Introduction

Chile is recognized worldwide for its broad and extensive network of preferential trade agreements (PTAs). According to data from Chile’s Undersecretary of International Economic Relations (2022), 95 percent of exports go to markets that have signed PTAs with Chile, and these exports are responsible for more than 17 percent of new jobs. This strategy of actively negotiating market access through PTAs is a key pillar of Chile’s foreign economic policy and is central to the implementation of its development model, particularly after the return to democracy in 1990. The negotiation of PTAs has enabled Chile to engage with international markets, leading to further trade liberalization. Since the 1990s, the strategy has enjoyed a high degree of national consensus and very low degree of politicization. In recent years, however, questions have arisen, particularly after the protests of October 2019 and the subsequent process of constitutional rewriting. For example, the social outburst and disagreement with the current economic model and its distributive effects led to a high debate on the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership/Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP/TPP), which was finally approved in parliament in 2023. From 2018 to 2023, expressions of civil disorder have been multiplied in the media and social networks. Questions have arisen regarding the continuation of signing PTAs.Footnote 2 The objections mainly come from concerns regarding the unequal distribution of benefits from trade openness and demands to implement a more active development policy. This opposition to trade policy as usual, primarily from public and civil society organizations, played an important role in the 2021 general elections when voters rejected the traditional parties and ultimately elected the youngest president in Chilean history. During his campaign and first year in government, he raised the need to rethink trade policy, and in particular his apprehensions about some provisions in agreements such as the TPP and about the treaty modernization project with the European Union (EU).

However, this study finds that a positive perception of PTAs still seems to be dominant in many segments of the private sector and in key government authorities. The political-economy literature has studied the features that shape public and elite perceptions toward free trade, focusing on various economic and sociotropic factors, and mainly for the cases where the EU and the United States were involved. Chile is a particularly interesting case to study, as free trade has long been seen as an important and successful element of its export-led growth economic model, and it has enjoyed significant public support. Yet, after the October 2019 demonstrations there has been a significant shift in public debate over the role of free trade in Chile, with significant concerns about its distributional and social effects becoming key topics. Much of these concerns catalyzed opposition to the CPTPP.

To determine to what degree perceptions toward PTAs have in fact changed, this chapter develops a mixed methodology based on stakeholder’s surveys, expert interviews, and media analyses. First, a stakeholder survey was conducted. Second, a content analysis of the two main Chilean newspapers was carried out covering the past five years to identify changes in media coverage over time. Finally, the results were contrasted with interviews with key stakeholders, such as former trade diplomats – Chilean Ambassadors to the World Trade Organization (WTO), Undersecretary of International Economic Relations Directors, and government officials – academics, and scholars at higher education institutions.

This chapter finds skepticism increasing, but at a low rate, among large segments of Chilean societies. Civil society laments negative distributional effects and costs on society and demands more access and inclusion to trade policy formulation and implementation. Also visible are continued fears that increasing market integration could lead to important structural changes in the future.

This disquiet has been more evident recently than at other times in its history, possibly because of the social and productive results of the Chilean model and the high expectations that trade policy would lead to structural economic changes. During the social unrest of October 2019, the number of TPP opponents and of anti-TPP slogans seen on banners or written on the walls of streets was striking. The debate regarding ratification and implementation of this agreement featured more prominently in the media than had any of the previously signed agreements. However, this does not seem to be evidence of a radical change in the perception of the country’s trade policy.

The chapter is divided into four sections. The first reviews the literature on perceptions regarding trade agreements. In the second section, the trajectory of Chile’s trade policy is described to provide understanding of key moments in time where turning points in general perceptions have occurred. In the third, the results of the surveys, the media analysis, and the interviews are presented and discussed. Finally, some conclusions are presented.

8.2 Literature on Perceptions of PTAs

Past literature has examined the factors shaping people’s attitudes toward free trade for at least two decades. These explanations range from classical economic models of factors of production to nationalism, fear of foreign cultures, and gender differences, amongst others (Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov2015). One area in which new studies have emerged is analyzing how PTAs shape attitudes toward trade liberalization. Initially, attention has been paid to identifying what makes some people support trade liberalization and others oppose it, and to characterizing the mechanisms behind this formation of preferences. There are different approaches ranging from direct economic self-interest to those that stress sociotropic concerns, as well as noneconomic concerns, which include cultural or social factors that shape attitudes.

The economic approach to people’s perceptions of trade liberalization predicts that individuals act and behave based on their income, which is related to factors of production or factor endowments possessed (Rogowski Reference Rogowski1989; Irwin Reference Irwin1995; Hiscox Reference Hiscox2001; O’Rourke and Sinnott Reference O’Rourke and Sinnott2001; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001; Margalit Reference Margalit2012). Yet, in recent years, this conventional wisdom has been challenged by a variety of studies showing that noneconomic factors matter as well. This work suggests that there are many other factors, not directly related to economic aspects, that may explain the observed variation in public opinion about free trade, including education, culture, gender, and nationalism (Mansfield et al. Reference Mansfield, Milner and Rosendorff2002; Walter Reference Walter2021).

Regarding noneconomic factors, education has received ample attention that effects attitudes toward trade. Hainmueller and Hiscox (Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2006) argue for example that education increases knowledge about the general benefits of trade to the economy, boosting support for trade liberalization among the more educated. Another differentiating factor is people’s age and their aversion to what is new.

Gender has been singled out as well as an important factor because women are systematically less inclined than men to favor trade liberalization (O’Rourke and Sinnott Reference O’Rourke and Sinnott2001; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001; Drope and Chowdhury Reference Drope and Chowdhury2014). In addition, Drope and Chowdhury (Reference Drope and Chowdhury2014) find that it is not women, per se, who favor protectionism, but, more precisely, economically vulnerable women because, as the factor endowment approach suggests, women are more sensitive than men to issues of economic security. More recent work demonstrates that women remain systematically less likely to favor trade because they are affected indirectly. Mansfield et al. (Reference Mansfield, Mutz and Silver2015) argue that “this gender difference is rooted in attitudes toward competition, relocation, and involvement in world affairs.”

Moreover, several authors highlight social and cultural consequences. Individuals who are concerned with these social-cultural effects are more disposed to view economic integration as harmful (Wehner Reference Wehner2007; Margalit Reference Margalit2012; Baccini Reference Baccini2019). Other studies find that respondents’ positive perception (or support) for trade liberalization is found to have a strong negative correlation with patriotic, nationalist, and chauvinistic views (O’Rourke and Sinnott Reference O’Rourke and Sinnott2001; Mayda and Rodrik Reference Mayda and Rodrik2005; Mayda et al. Reference Mayda, O’Rourke and Sinnott2007). Similarly, Mansfield and Mutz (Reference Mansfield and Mutz2009) found that the impact of nationalism on trade preferences must be considered, given the tendency for some individuals and cultures to be ethnocentric and isolationist.

The literature regarding the role of interest groups that support or oppose trade has been well developed in the case of the European Union and the United States (Grossman and Helpman Reference Grossman and Helpman2002; Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2014; Gheyle and De Ville Reference Gheyle, De Ville, Dialer and Richter2019; De Bièvre and Poletti Reference De Bièvre and Poletti2020; De Bièvre et al. Reference De Bièvre and Poletti2020). These contributions increase our understanding of the interaction among lobbying groups, public opinion, and the increasing legitimizing pressure of trade agreements.

Some studies demonstrate that country characteristics seem to matter in the public’s eyes. Dür and Huber (Chapter 3) find that political ideology, and to a lesser extent, geopolitical concern, seem to play a role in determining which individuals are viewed as favorable PTA partners. Citizens in developing countries prefer countries that are culturally similar, democratic, and consider security issues and high environmental and labor standards (Spilker et al. Reference Spilker, Bernauer and Umaña2016; Cherry Reference Cherry2018; DiGiuseppe and Kleinberg Reference DiGiuseppe and Kleinberg2019; Bush and Prather Reference Bush and Prather2020). For example, Minard and Landriault (Reference Minard and Landriault2015) find that the public is unwilling to support treaties with China due to the characteristics of the regime’s political system.

In short, the perception of trade policy, of which PTAs are an integral part, will depend, then, on several factors including levels of education, culture, exposure, and economics. Individuals’ views about the effect of liberalization are driven by sociotropic concerns, rather than a direct assessment of the effect of trade liberalization in purely economic terms (Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov2015).

In this context, the world has seen a rising backlash against globalization. Recent research shows, that contrary to a popular narrative, the backlash is not associated with a large swing in public opinion against globalization but is rather a result of its politicization (Walter Reference Walter2021). Both material and nonmaterial causes drive the globalization backlash, and these causes interact and mediate each other. The consequences are shaped by the responses of societal actors, national governments, and international policymakers. These results are more complex if we distinguish between the perceptions of elites and citizens. A recent study, published by Dellmuth et al. (Reference Dellmuth, Scholte, Tallberg and Verhaegen2022), mapped legitimacy beliefs toward six key international organizations, among them the UN, drawing on elite and citizen survey data from Brazil, Germany, the Philippines, Russia, and the United States. They found a notable elite–citizen gap for all six organizations studied in four of the five countries. This gap between what contemporary elites and citizens think about globalization might bode ill for the future of global institutions and trade agreements.

This section has limited itself to reviewing some of the findings in the literature that studies the perception vis-à-vis free trade, focusing on PTAs. As seen, there is limited literature for Latin America. In the following sections we will assess to what degree a change in attitudes in Chile can be explained by existing arguments, or whether additional country- or context-specific factors need to be brought in.

8.3 Chilean Trade Policy

Trade policy in Chile is an essential part of its foreign and economic policies. Even more so, it is considered a key element of the development strategy since integration into the world economy has been seen as a growth engine. Thus, various contributions to trade policy have reflected the growing importance in the framework of Chilean foreign policy (Frohmann Reference Frohmann1991; Agosin Reference Agosin1993; Hachette Reference Hachette1993; Velasco and Tokman Reference Velasco and Tokman1993; Sáez and Valdés Reference Sáez and Valdés1999; Lopez et al. Reference Lopez2022).

During Pinochet’s regime, under the paradigm of liberalism, an aggressive trade opening plan was implemented. Given the country’s partial international isolation, the government followed both a path of unilateral reduction of tariff and nontariff barriers on the one hand (Hachette Reference Hachette, Larraín and Vergara2000; Ffrench-Davis Reference Ffrench-Davis2003) and of multilateral negotiations within the framework of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) on the other (Jara Reference Jara, Estevadeordal and Macau2005; López and Muñoz Reference López and Muñoz2018).

With the return of democracy in 1990, the foreign affairs priorities of Chile were an expression of a political discussion that placed emphasis on finding a consensus on a development model and increasing trade relations with countries. This reasoning was initially marked by the narrative of “international reinsertion” (Tomassini Reference Tomassini1990; Heine Reference Heine1991). Along with the decision to maintain and deepen the neoliberal model, a strong push led to the negotiation of PTAs as well as the strengthening of the idea of joining subregional integration schemes such as Mercosur or the Andean Pact (DIRECON 2009). The main objective was to speed up the integration of Chile into the world economy after years of international isolation during the dictatorship period. In fact, since the third United Nations Conference on Trade and Development which took place in Santiago in 1972, Chile has enjoyed a society-wide consensus on the importance of integration in the world and cooperating closely with other trading partners (UNCTAD 1973).

In 1990, with the beginning of the democratic period, the country started a process of bilateral negotiations (Economic Complementarity Agreements (ECAs)), focused mainly on goods, within the framework of the Latin American Integration Association (LAIA).Footnote 3 This process became known as “open regionalism” (Rojas and Solis Reference Rojas and Solís1993; Van Klaveren Reference Van Klaveren1994) and guided Chile’s economic integration model when Chile was a young democracy seeking PTAs with the major markets in the world. These agreements rested on a discourse focused on Latin American integration. This has been defined in the trade policy of Chile as a different strategy to accelerate the economic integration process (Wilhelmy and Durán Reference Wilhelmy and Durán2003).

For several years there was wide consensus over the virtues of an open integration strategy. However, a few critical voices were raised during the negotiations with Mercosur between 1994 and 1996. Few sectors that still maintained protection (e.g., in agriculture) were in direct competition with imports from the South American bloc. To address internal pressures from the import-competing sectors and unions, the government compensated groups that claimed to be damaged through increased competition (Porras Reference Porras2003). This was done to appease opposition while the decision was taken to submit the signed agreement to Congress for ratification, even though this was not needed within the framework of the LAIA (Porras Reference Porras2003). The opposition consisted mainly of the National Agricultural Society (SNA) and of interest groups that did not want the country to be subject to a common tariff regime and instead favored another type of “insertion” model.

After Mercosur, the trade debate centered around a potential membership of Chile in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (López and Muñoz Reference López and Muñoz2018; Lagos Reference Lagos2001; Porras Reference Porras2003; DIRECON 2009). In this case, the government saw NAFTA as a more attractive agreement to join than Mercosur. However, the internal resistance of unions in the United States, together with the fact that President Clinton failed to obtain the necessary fast-track authority from the US Congress, complicated Chile’s inclusion in this treaty. As a result, the Chilean government began separate negotiations with Mexico and Canada. Thus, Chile signed a PTA with Canada in 1997. This agreement proved to be very important since it provided a seal of approval signaling that Chile was continuing its strategy of active economic integration. It also kept open the possibility of joining NAFTA at a later stage. In 1998, it broadened its economic complementation agreementFootnote 4 (ACE) with Mexico, bringing it even closer to a trade agreement model more applied by Northern countries. The last NAFTA country with which Chile signed a PTA was the United States in 2003. It was wide-ranging and one of the most progressive trade treaties at the time, because it was one of the first to include provisions on labor and environment.

After these initial successes, momentum to negotiate PTAs continued. Civil society and the business community appeared to support the idea that this was the path to growth and development. Thus, in 2003, the Economic Partnership Agreement with the European Union was signed, which expanded the classical trade treaty structure by incorporating political, economic, and cooperation aspects.Footnote 5 The decade of the 2000s was characterized by the increasing emergence and role of Asian economies on the international stage, what the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) would later refer to as the “Asian factory” phenomenon. In addition, China entered the scene with its accession to the WTO in 2001, eventually becoming the largest economic actor in world trade. In 2004, Chile hosted the sixteenth (XVI) annual meeting of the Forum for Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in Santiago, with the motto of One Community, Our Future. This was of great symbolic importance, as it was the first time that an Andean country held the presidency of the organization.

Chile has continued to focus extensively on the Asia-Pacific region. In April 2004, a PTA between Chile and South Korea was concluded. Shortly after, in 2006, an agreement with the People’s Republic of China was finalized.Footnote 6 During that same year, negotiations of the Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement with Brunei Darussalam, New Zealand, and Singapore, known as P4 (the predecessor of the TPP-11 initiative), were concluded.

These were years of intense activity for trade policy. In 2007, a partial scope economic agreement with India and an Economic Association Agreement with Japan entered into force. The partial agreement with India includes trade disciplines in limited areas of market access, rules of origin, customs procedures, safeguards, and dispute settlement while in contrast, the PTA with Japan has had a broader scope, including disciplines on services, intellectual property, and investment among others. In 2008, a PTA with Panama was signed, while in 2009, PTAs with Peru and Colombia came into force, through a process of expansion of the ECAs. These agreements include most of the disciplines that each country commits to in their PTAs with the United States and go beyond goods and services. Similar agreements were later finalized with Australia (2009), Malaysia (2012), Hong Kong, Vietnam (2014), and Thailand (2015).

In 2009, based on the P4, the United States pushed to shape a regional agreement that would have broad membership and high standards (Gallegos Zúñiga and Polanco Reference Gallegos Zúñiga and Polanco Lazo2013). Australia, Canada, Japan, Malaysia, Peru, and Vietnam joined this project. It was an ambitious agreement and one that included a large number of issues that have caused internal debates, such as the strengthening of intellectual property rights, a new deal for state-owned enterprises, which is based on the principle of competitive neutrality and seeks to harmonize the internal policies of each Member State in this matter. Likewise, a chapter on small- and medium-sized companies is included, which is novel since it is the first time that there are provisions on this topic, and its content is informative although it does not fall under the dispute resolution chapter of the agreement.

Today, Chile has a network of thirty-three trade agreements of different depths and scopes. More recently, it has embarked on modernizing some of these and has explored the inclusion of new topics such as gender and the digital economy, among others. Within the context of modernizing the agreement with Canada, important progress was made by including a chapter on gender and trade, which was signed in 2016. This chapter was included for the first time in any world agreement in the PTA with Uruguay. The attention to gender is closely linked to the leadership of President Michelle Bachelet, who served as president from 2014 to 2018 (López and Muñoz Reference López and Muñoz2021). As a result, Chile has been an active participant in the creation of a technical group on gender and trade in the Pacific Alliance and in the APEC Forum. More precisely, in the APEC’s Roadmap on Women and Inclusive Growth, Canada, Chile, and New Zealand established the Inclusive Trade Action Group (ITAG) on the sidelines of the 2018 APEC leaders’ summit. Chile has also been engaged actively in another new issue area: the digital economy. In 2020, Chile was the first country to sign the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA), an agreement on the digital economy that the Chilean Undersecretariat for International Economic Relations (SUBREI) has highlighted as innovative in its structure and negotiation.Footnote 7

Chile has continued its policy of entering into trade agreements, in 2022, the PTAs with Brazil and Ecuador, countries which usually are reluctant to engage in any trade negotiations, came into force. It is also working on the modernization of its agreements, such as with Mexico; finalized the agreement with Paraguay in 2024; and is in negotiations with India, among others.

However, not all trade projects have been free of criticism. When Chile began to study the “modernization” of the Agreement with the European Union, as well as during the TPP negotiations, some controversial issues emerged – concerned with topics such as natural resources and investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).

On natural resources, the EU proposed an article on export prices, which would have prevented Chile from offering preferential prices for lithium and other raw materials to companies offering “value added.” Regarding the resolution of investment disputes, the government considered signing “side letters” to exclude recourse to ISDS, following New Zealand’s practice. However, this strategy yielded few results. Chile reached such an agreement just with New Zealand on February 17, 2023, and, apparently, similar side letters with Mexico and Malaysia, although they are not publicly available.

Whereas politicization has increased over the years, overall support for trade has not in any significant way decreased but rather increased, as various surveys have documented. The Public Studies Center (CEP) has developed and conducted a national public opinion survey about attitudes and perceptions of the population since 1987.Footnote 8 Some questions in the survey focus specifically on free trade. The data in 2023 has shown that 72 percent of the respondents considered that Chile can have access to better products, thanks to international trade;Footnote 9 81 percent agree that Chile should continue to expand trade with other countries; and 68 percent consider that foreign investment should be encouraged.

When questions relate to imports more specifically, the CEP surveys actually show that compared to twenty years ago, more people see imports in a positive way. When the statement was formulated as follows: “Chile should limit the import of foreign products to protect its national economy,” 58 percent of respondents answered that they strongly agreed with the statement. By 2022, the level of agreement with the statement fell from 58 percent to 43 percent. The size of the group that neither agrees nor disagrees increases slightly from 14 percent to 18 percent, and the percentage that strongly disagrees with the statement increases from 22 percent to 36 percent.

Similarly, the surveys conducted by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), through the Latinobarómetro cross-regional survey, reveal that popular support for international trade remains strong, with 73 percent of citizens in 2018 in favor of increasing trade. However, surveys also show that if politicians warn of job losses due to lower trade barriers, and if the media and social media promote such arguments, support for trade may wane through such framing effects. This also means that the stability of preferences might be somewhat volatile, and it makes a difference how, and by whom the arguments for and against free trade, are presented.

In summary, since the implementation of what has been defined as the neoliberal model during the 1970s, trade liberalization and international insertion have benefited from a broad consensus. With respect to PTAs, some disagreement became visible as witnessed in the talks with Mercosur on agricultural liberalization, with New Zealand on dairy products, as well as with the United States on investment protection. But in general, the opposition was largely limited to affected sectors. These concerns were addressed by the government and therefore did not spill over to significant public discussions. This changed with the debates about TPP, where the involvement of Chilean society was evidently greater, also driven by a notable increase in news coverage. This led to greater politicization and a questioning of the dominant “neoliberal model.”

8.4 Perception of PTAs: Insights from a Stakeholder Survey, Media Analysis, and Interviews

The recent emergence of increased politicization of trade agreements in Chile can be observed in both discussions and debates in the traditional media and on social media. Trade policy is today a more salient issue among different stakeholders than it was prior to the TPP. To identify the perception of trade and PTAs and potential shifts, this study uses insights from three complementary sources.

First, data from an elite stakeholder’ survey provides valuable insights on elite perceptions. The sample consists of fifty-one respondents ranging from trade diplomats, academics, and private sector representatives. Second, the chapter carries out a media content analysis to capture the PTAs’ politicization over time. Third, information from twenty-one in-depth interviews with experts on Chile’s trade policy is used to complement the analysis. The interview partners are drawn from a mix of former trade diplomats (Chilean ambassadors to the WTO, SUBREI Directors, and government officials), academics, and scholars at higher education institutions. Due to confidentiality reasons, the interviews have been anonymized.

Regarding the elite survey, the response rate has been 17 percent, totaling fifty-one overall, and are valid responses to the questionnaires sent to experts. The sample consists of 74 percent men and 24 percent women. The questionnaire was sent by email with a purposive sampling. Moreover, 52 percent of the sample live in the Metropolitan Region, 46 percent in other regions, and only 2 percent outside Chile. Regarding the educational level, 16 percent hold a doctoral degree, 46 percent a master’s degree, 62 percent a bachelor’s degree, and one had only finished high school education. The data was collected between March and August 2022.

The print media review was conducted through a content analysis including the two newspapers with the largest readership in Chile: La Tercera and El Mercurio, from January 1, 2017, to August 8, 2022. After subscribing to the journals to access the historical files, a total of forty-six relevant news items were identified through the search functions for subscribers of each journal. Subsequently, a sentiment analysis was carried out following Bardin (Reference Bardin2002) to identify positive and negative news. In addition, concepts and their frequency were mapped out. As for the general procedure of sentiment analysis, the news was manually separated into positive and negative in relation to how much they promoted or opposed trade agreements. Figure 8.1 provides an overview of thirty-one news with positive sentiments and fifteen with negative sentiments. As the frequency analysis shows, we divided different concepts falling in the positive and negative categories, respectively, and counted the number of times they were mentioned (frequency) (see Figure 8.2).

The purpose of the twenty-one interviews with specialists in Chilean trade policy experts was to deepen our understanding regarding the identified issues in the survey and the media review. These interviews also made it possible to contrast the critical views of PTAs found in public discourse with those of the experts. The interviews were conducted in person as well as remotely. The questionnaire was semi-structured with an emphasis on exploratory questions. The authors are cognizant that for former officials, their support in favor of liberalization and a policy of openness may be conditioned by their experiences occurring during the military regime where the country was closed to international trade.

8.4.1 General Perception Regarding Trade and PTAs

We proceed by first conducting a comparative analysis with the data collected from the three different methods to identify the importance attributed to international trade. The survey data shows that respondents overwhelmingly see trade as “very important” (96 percent), and only one respondent considers it to be “fairly important” and one respondent “indifferent.” This confirms that integration into international markets is still perceived to be a very positive strategy by trade experts. Approval drops a bit when the question focuses on PTAs specifically, with 84 percent of respondents indicating that they are “very important” and only one respondent that they are “fairly important.” One possibility is that this reflects growing negative sentiments toward the TPP/CPTPP after 2019 or a minority view of a fairly limited impact on society.

Using the data retrieved from the two main newspapers, we observe that since 2017 the number of news items addressing PTAs in general has increased consistently, indicating that the issue has potentially become more salient. We observe a drop in attention for 2020, when the COVID pandemic likely took center stage and PTA negotiations were also stalled. Also, 65 percent of the news items could be classified as positive in their description of trade agreements.

Between 2017 and 2020, news items with a positive message outnumbered negative ones, even during the period of social unrest in 2019, when opposition to the TPP was observed (Figure 8.3). The trend started to shift in 2021 and in 2022 we see a steep rise in negative news. It is important to consider that both newspapers are privately owned and are considered to editorially reflect conservative and right-leaning positions. Therefore, the negative news trends could also be explained by opposition to President Boric’s type of trade policies, something these newspapers have questioned since the presidential campaign.Footnote 10

As Figure 8.3 shows, after 2020 the negative news increased in frequency. This could be related to the 2019 social movements directly questioning the neoliberal economic model and, as a representation of this, the network of PTAs. During the political campaign and the first year of President Boric’s administration, there was a lot of criticism of the so-called free trade policy of former governments. What was also questioned was the dependence and reliance on exporting natural resources, in particular copper.

Turning to interviews, in general, trade experts hold the view that PTAs have benefited the country because they have improved market access, led to growth due to the reduction of tariffs and trade barriers, lowered consumer prices, and strengthened Chile’s position abroad. One respondent illustrates this sentiment

well: In general, Chile’s trade policy – what it was, and what has been Chile’s integration strategy in commercial economic matters during the last three decades – has been fundamental for the country’s growth. It has been a pillar from the point of view of its contribution in terms of expanding markets. … In addition, it seems to me that it has given the country a brand.

Most interviewees, when asked to share their view on PTAs, held that they were a tool to boost exports and imports of the country for two main reasons: (i) because of tariff reductions and the elimination of trade barriers and (ii) by allowing the exchange of goods and services in profitable conditions and without discrimination. Overall, there is a strong perception that PTAs have positive effects for both producers and consumers as they provide better development opportunities for the country because the economy becomes more competitive. The rest of the respondents, close to 40 percent, answered that PTAs were just agreements between two countries, but they did not elaborate more on their effects.

Below, we show the results of a “word cloud” that summarizes the most used words when respondents were asked about the meaning of a PTA for them. We can see that answers are oriented around economic and trade concepts. And the answers tend to describe PTAs economic objectives.

We contrast above word cloud (Figure 8.4) with a second one (Figure 8.5) drawing from the media analysis. We can see that for this data, the most common words are not necessarily related to classic economic concepts except for the term “growth.” Also, trade-related and non-trade issues tend to appear most frequently. The results show that the “survey respondents” are focusing on economic matters, whereas the right-leaning media is covering many noneconomic objectives, such as sovereignty, democracy, and potentially the costs as evidenced by the word “consequence.”

In the survey, the respondents were also asked explicitly what positive attributes they give to the agreements, providing a set of multiple-choice answers. Table 8.1 shows the responses according to frequency. The most critical aspects are closely related to the fact that they are associated with facilitating investments, trade in goods and services, and supporting diversification in export baskets.

If we focus on the data from the content analysis of the media, the most frequently used words related to PTA effects were country-reputation, sovereignty, neoliberalism, revise, trust, democracy, growth, protectionism, incorporation of new topics, integration, negative consequences of updated PTAs, negative impacts of PTA. These are broader than the expressions found in the responses to our questionnaire, where the topics were primarily commercial in nature.

Taking a closer look at the media content analysis, we see the different categories also in Figure 8.6 and how they are associated with positive and negative attributes of the agreements.

In the following, we look in more detail at some of the categories.

8.4.1.1 Modernization

In the first category, modernization,Footnote 11 most of the news items reviewed suggested that Chile continues on the path of deepening and expanding the network of agreements. In particular, it must strengthen its bilateral ties and not abandon its path toward lifting barriers in order to increase trade. The government should continue improving the existing agreements, exploring new topics (e.g., gender), and strengthening economic relationships.

8.4.1.2 Growth

On growth, the second-most mentioned category, the role of PTAs was underscored as a fundamental element in the country’s growth and development, terms that were used synonymously in most cases. Export-led growth is also pictured as a stimulus to employment and innovation, as well as higher wages. PTAs were also described as instruments that make the economy more dynamic, as they help increase the availability of products for consumers, lead to lower prices, and improve access to technologies.

8.4.1.3 Integration

Interesting to note is the perception that PTAs are an obstacle to integration within Latin America, particularly with Mercosur. This perception may be shaped by the Chilean government’s argument that Chile could not join Mercosur as a full member because of the common tariff imposed. However, Chile wanted to join NAFTA, and increase relations with more open economies and developed countries.

8.4.1.4 Revision

Since 2019, the idea of opting for unilateral revisions of PTAs and the possibility of derogation of existing commitments received increased attention in the public debate. This then resulted in a counter-campaign by different sectors, arguing that such a move would damage the country’s image or reputation. Furthermore, during the period in 2021 in which the work of the Constitutional Convention took place, the discussion of considering to go through the PTAs was present in the media analysis.

8.4.1.5 Sovereignty

The most critical view can be observed in relation to the sovereignty category. Many news items pointed out that the agreements impose conditions that limit the countries’ freedom of action. These comments are related to criticism leveled against the TPP, such as the lack of civil society participation in the negotiations, an argument expressed for the first time in any PTA negotiation process.

The fact that Congress can only authorize trade talks and reject outcomes of the negotiations without being involved in the process of negotiations began to be questioned. Some of the criticism regarding the lack of the parliament’s involvement went hand in hand with negative views on job protection, concerns about the lack of inclusiveness, and unbalanced distributive impacts.

Contrasting these media views with information from the elite interviews, we observe that the latter shows more pragmatism when it comes to sovereignty. Interviewees pointed out, for instance, that any treaty or agreement naturally implies ceding some degree of sovereignty. Yet, none of the treaties that Chile has signed restricted its core ability to act or its sovereignty. Indeed, specific clauses in the treaties provide protection in this respect. One interviewee stated the following: The WTO in general and all the bilateral treaties that Chile has signed explicitly state that the regulatory capacity of the State remains intact, that is, there is no limitation of sovereignty (Interviewee 4).

Equally, all the interviewees pointed out that the most negative perceptions of the plurilateral treaties were due more to the political situation after 2019, the constitutional discussion, and the approval of the TPP, than being a concrete criticism of specific PTAs. The following three responses by interviewees illustrate this stance:

That break is determined by the TPP, not by the type of agreement. There is not a criticism against multilateralism per se, but it is a criticism against the TPP. (Interviewee 1)

This is because the discussion focused on the TPP, but I don’t see why public opinion can understand the difference between a bilateral or plurilateral agreement. (Interviewee 2)

8.4.2 Specific Perceptions regarding PTA Provisions

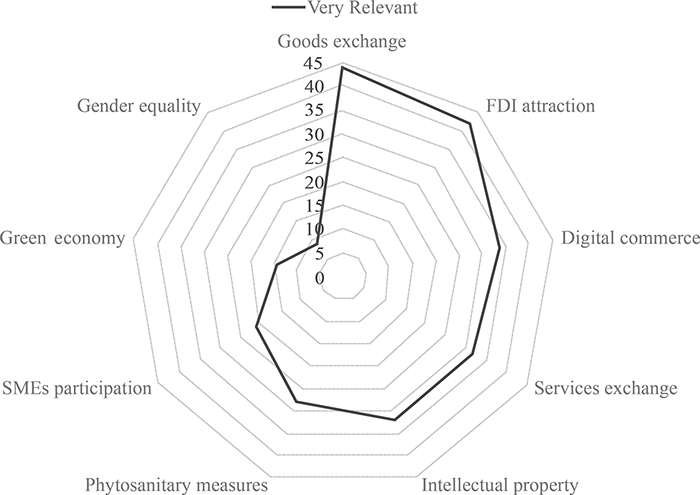

Dür et al. (Reference Dür, Huber, Mateo and Spilker2023) argue that interest groups’ positions toward trade agreements depend on the specific design features of trade agreements. Depending on which issues are covered in a trade agreement, a group may be supportive of that agreement. In the survey we asked the participants to indicate how important an agreement is in relation to different objectives. A list was provided, and they were asked to rate them according to their relevance (see table in the Appendix). This allowed us to make a comparison and to rank their importance. In Figure 8.7, the results are shown according to the order of importance from the highest to the lowest.

Figure 8.7 How important is a PTA for the following reasons.

8.4.2.1 Intellectual Property, FDI Promotion, and Digital trade

The most supported categories are Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) promotion, digital commerce, intellectual property, phytosanitary measures, and services trade. The category “Small and Medium enterprises” received support but to a lesser degree. This finding is consistent with one of the criticisms against PTAs that they have not been a substantial instrument to strengthen the role of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). The increasing inclusion of SMEs and trade in services, however, could be explained by the willingness of recent governments to improve opportunities for service providers, increase export diversification, and reflect the important role of agriculture, and smaller-scale farmers, in the Chilean economy.

The importance given to FDI promotion could be both positive and negative. On the one hand, concerns about the slowing of investment (as also present in media reports) would suggest more importance to FDI concerns. On the other hand, the salience of FDI is also related to increasing concerns about private investors suing the Chilean state and therefore needing clear rights and obligations in the PTAs.

When it comes to the increasing importance of digital trade that entered the political debate in Chile, this is often related to the role of media platforms, the taxing of international streaming services, such as Netflix, but also more generally important to digitalization as an effect of the pandemic.

Finally, the moderate attention to “intellectual property” could be a result of the debates during the TPP negotiations. In one interview, it was argued that Chile lost out in terms of intellectual property in the PTA with the United States. In this sense, it was mentioned that the PTAs can have a chilling effect on public policies in the country, especially those related to the promotion of industrial policies.

8.4.2.2 Gender and Green Economy

From the survey, we observe that gender and green economy topics appear to be less relevant. By contrast, these topics are frequently covered in the media. From the interviews, we can gather some more nuanced perspectives on their growing importance. Some suggest that Chile should aspire to similar levels of ambition as witnessed in most developed countries.

One interviewee put it as follows: It is important and necessary that these issues [gender] are included in the agreements. Above all for a small or at the most a middle-sized country like ours [Chile] (11).

However, although interviewees differed on the effectiveness of integrating these nontraditional issues into PTAs, they shared the view that these topics needed more attention.

Gender: In recent years gender policies have become a more important topic in Chile. This is in line with the contribution by Bahri (Chapter 4), who shows that several countries, including Chile, have been at the forefront of incorporating gender provisions in PTAs. Similarly, the chapter by Caceres and Munoz (Chapter 9) demonstrates that trade agreements enhance women’s service sector employment, which can have positive effects, potentially, for the goal of gender equality. Figure 8.8 plots perception of survey respondents about the PTA relevance for gender equality according to their place of residence (urban vs. rural).Footnote 12 The data shows that survey respondents who reside in rural areas are slightly more in agreement that PTAs are relevant for gender equality.

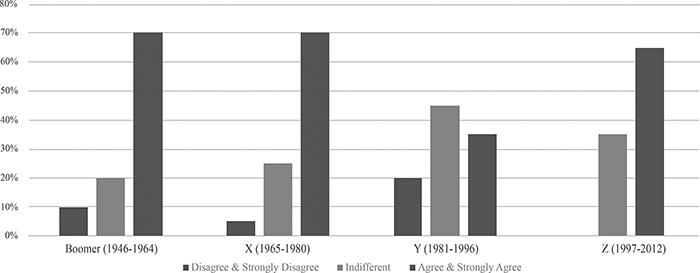

The generational rift is less evident in perceptions of the gender perspective. However, there is a tendency for younger generations such as millennials (category Y) to agree less that PTAs have a positive impact on reducing gender gaps (Figure 8.9).

The interviewees mentioned that these differences in perception observed between generations are mainly due to specific life experiences. One interviewee shared the following explanation:

This is partly because the list of concerns is different for an older generation than it is for a younger generation. For example, the challenges related to the environment and climate change were not so dramatic a few years ago.

Moreover, some interviewees added that, although the millennial generation is, in comparison to other age groups, more critical in its views of free trade and international treaties, this does not mean that they want more protectionist measures to be applied. On the contrary, this is a generation that enjoys freedom of choice. It could be argued then that millennials’ critiques are directed more at the standards used in international trade on issues such as the environment, gender, or labor rights than at trade itself. One interviewee stated the following:

Millennials are a generation that operates in a tremendously open and connected world. They are a very libertarian generation, with a position towards life in which they want freedom of expression and thought and are free to consume what they want. And even if they have critical views, that does not translate into formulas that amount to protectionism.

Green economy: The survey also focused on the relevance of the topic of green economy to be included in PTAs. Similar to gender provisions, more and more PTAs in Latin America include environmental provisions as documented in the chapter by Klotz and Ugarte (Chapter 6). Results of the survey show that most respondents considered this topic important (57 percent). When focusing on survey respondents’ place of residence, we observe that outside the Metropolitan RegionFootnote 14, the support for the statement that PTAs are significant for the green economy received less support. Also, 19 percent of people living outside the Metropolitan Region found no relevance in relation to the green economy (see Figure 8.10).

Looking more closely at the survey data on whether any generational difference exists in perceptions of the role of PTAs in matters related to the green economy, the results are mixed. As far as perception of the green economy is concerned, younger generations are more skeptical regarding the role that this type of agreement can play on this issue. As shown in Figure 8.11, a smaller percentage of both millennials (Generation Y) and Generation Z respondents agree that PTAs support the green economy. Older generations such as baby boomers and Generation X, meanwhile, tend to be more in agreement that PTAs have a positive relationship with the green economy.Footnote 15 This may be a result of the priority given to environmental issues, which have become an increasingly important part of people’s lives over time.

8.4.2.3 Other Relevant Regional Results

The survey found a difference in perception between people from Chile’s more urban regions and the Metropolitan Region. The experts pointed out that the difference may be due to the different role played by the regions compared to the Metropolitan Region in the production of the different goods that Chile exports. It is important to recall that the mining sector is highly concentrated in the north of the country, being close to 60 percent of the country’s exports. And the south center regions are the main agricultural exporters, representing the second-most important commercial sector for Chile. One interviewee stated the following:

People from the Regions, not from Santiago or Metropolitan Region,Footnote 16 are much closer to their personal experience with export results. Because 80% of the goods that Chile exports come from the regions.

People are more likely to benefit from exports, for example in terms of employment.

On the scope that PTAs should cover, opinions differed as well amongst interview partners. Some voices were particularly skeptical about issues beyond the core objective of trade liberalization as captured in the following statement:

PTAs are not an instrument of economic policy to solve all problems. … I am a bit skeptical that PTAs can help to correct gender issues. The same applied to climate change. I would be in favor of alternative instruments; the fact is that those issues are lost among the hundreds of articles and chapters that a PTA contains …, It is better to explore more ad hoc instruments.

8.4.2.4 Additional Insights from Interviews

In this final section, we briefly discuss additional views shared by interviewees that might deserve further exploration. First, regarding the increasing politicization of Chile’s trade policy and the negotiation of PTAs, the interviewees did not consider this development negatively. There was no opposition to citizens and civil society showing more interest in trade policy as illustrated by the following statement:

Ideologization is not bad in itself, in the sense that it does not seem bad to me that an agreement becomes politicized when it is discussed. I understand that this gives it more content. … We have even gained something from all that happened with the TPP—we have made people talk about issues that they had never talked about … that is a positive side-effect.”

Second, it was also stressed that information needs to be fact-driven and should lead to better knowledge. This aspect was also prominent in the media coverage, in which it was pointed out that the issues, being rather technical, were more difficult for the general population to understand, making it more likely that misinterpretations would occur, or fake news would spread. This was captured by the following statement:

There is a lot of ignorance about the content of the treaties, caricatures have been made about them that do not help the discussion much.

Third, while the TPP led to increased politicization, the content of TPP was not that novel as stated by one interview partner:

8.5 Conclusions

This chapter has shown that the past consensus view related to Chilean trade policy has undergone a change. However, contrary to our expectations, the views regarding PTAs are not as negative as expected due to the social outbreak/unrest in 2019 and the politicization over TPP. It seems that many of the issues raised by the protesters were not necessarily related to the PTAs itself.

Our results from different data sources suggest that Chileans’ elites and media seem to have reached a consensus that PTAs are necessary for economic growth. The perceptions of PTAs are still dominantly positive, whereas the media coverage has tended to become more negative. The chapter finds that not even the most critical voices related to PTAs seek to return to protectionist policies; rather they demand that PTAs become more inclusive and focused on achieving development objectives. Specifically, they show strong preferences for sovereignty, democracy, gender, and the environment. Clearly, further research is needed to better capture the degree of individuals’ knowledge and understanding of PTA effects.

The results further suggest that the population from Chile’s regions and older generations have a more positive perception of PTAs, mainly due to the importance of the exporting sector in rural areas. The results also show the older the individuals the more positive their assessment. This may be explained by their exposure to successful trade liberalization after the military regime. The criticism of younger generations needs to be interpreted as nuanced, as they don’t oppose trade per se, but wish to see more attention paid to the environment, gender, or community rights, and the impact of trade on development. It also suggests, related to the trade policy literature, that older generations’ attitudes reflect more egocentric and economic preferences, while younger generations are increasingly driven by sociotropic preferences.

Finally, this chapter calls for more research into public opinion and how it will affect the conduct of trade policy in Chile in the future. Will a more informed and engaged public demand changes for the future content of PTAs and treaty partners? How will policymakers engage with a more politicized trade policy environment? And finally, will PTAs remain a dominant instrument of shaping trade cooperation, or will new instruments arise?