9.1 Introduction

Preferential trade agreements (PTAs) are usually viewed as policy devices that can help increase trade flows between countries and promote economic growth and development. In recent decades, however, a progressive expansion of PTAs has been witnessed, both in the number of economies that participate, and in the topics they address and the depth of obligations that are agreed upon (Mansfield and Pevehouse Reference Mansfield and Pevehouse2013; Chacha and Nussipov Reference Chacha and Nussipov2022). From originally mostly trade-only treaties, PTAs have become complex instruments that address aspects of trade liberalization and a variety of non-trade issues, many of which can impact domestic regulations (Limão Reference Limão2007; Lechner Reference Lechner2016; Milewicz et al. Reference Milewicz, Hollway, Peacock and Snidal2018; Lake and Krishna Reference Lake, Krishna and Banerjee2019).

Including provisions related to trade in services is a good reflection of these agreements’ evolution (Marchetti and Roy Reference Marchetti, Roy, Marchetti and Roy2008; Roy Reference Roy, Sauvé and Shingal2014). Due to their characteristics and modes of international trade supply, service agreements contain provisions that consolidate market access and nondiscriminatory regulations concerning foreign competitors and domestic suppliers (Francois and Hoekman Reference Francois and Hoekman2010; López and Muñoz Reference López and Muñoz2016). Service provisions are different from those for trade in goods in that they typically affect regulations of a domestic nature that act as a barrier to trade. To date, the nature and drafting of these provisions and the lack of disaggregated trade data have made it difficult to assess their impact (Francois and Hoekman, Reference Francois and Hoekman2010). Moreover, it has been recognized that reforms driven by PTAs may go beyond those governing international trade flows, for which impact assessments should not be limited to bilateral exchanges of goods.

At the same time, there is an increasing awareness of the differentiated impact of trade policy and PTAs on men and women (Brussevich Reference Brussevich2018; World Bank and WTO 2020; Cáceres et al. Reference Cáceres, Muñoz, Alarcón, Chávez, Fierro, Guzmán and Rogaler2021). Economies have an inherently “gendered structure,” making it important to assess economic policies’ impact on gender inequality (Ridgeway and Correll Reference Ridgeway and Correll2004; Ridgeway Reference Ridgeway2011; Rai Reference Rai, Elias and Roberts2018; Momsen Reference Momsen2019). Specifically, while some economic policies may contribute to reducing gender disparities and enhancing women’s economic autonomy, others may have a negative impact, increasing the gaps between different population groups, such as men and women (Cáceres and Muñoz Reference Cáceres, Muñoz, Baisotti and Moscuzza2023a).

This chapter looks at the case of Chile to analyze the impact of the inclusion of service provisions in PTAs on the gendered structure of the economy. Chile is characterized by both an open economy based on a dense PTA network and deep gender inequalities. Chile has further been recognized as a small open economy whose economic development strategy was based on the integration of international trade, with an active policy toward the use of PTAs, including service provisions (López and Muñoz Reference López and Muñoz2015, Reference López, Muñoz, Mulder, Fernández-Stark and Álvarez2020; López et al. Reference López, Muñoz, Mulder, Fernández-Stark and Álvarez2020). Over the years, Chile has built one of the largest PTA networks worldwide, which in 2022 reached thirty-three agreements with sixty-five economies, covering developed and developing economies in the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Oceania, which represented 67 percent of the world population and 88 percent of the global gross domestic product (GDP) (SUBREI 2022). At the same time, the country faces substantial disparities between men and women, with inequalities that range from unequal participation in labor markets and wages earned from these activities to the uneven allocation of housework and gender differences in time use (De Paula Reference De Paula2018; Fuentes and Vergara Reference Fuentes and Vergara2018).

The chapter’s objective is to assess the impact of the inclusion of trade in service provisions on the participation of women in the labor force, particularly within the services sector. In the case of Chile, women tend to have more robust involvement in tertiary activities (services) rather than primary (mining, forestry, aquaculture) or secondary (mainly mining processed goods). Following previous studies that have linked trade in services and gender (Sauvé Reference Sauvé2020; Johannesson and Nordås Reference Johannesson and Nordås2021), this chapter works with the hypothesis that the inclusion of solid service provisions within PTA may enhance the development of this sector and should, in turn, have a positive impact for women’s employment. For this reason, a more substantial effect of PTA on women’s employment rather than men’s should be observed, which should help reduce the gender gaps in this sector.

To address these conjectures, the chapter builds on two streams of literature. On the one hand, it engages with scholarship that focuses on the drafting and inclusion of service provisions in trade agreements. On the other hand, it speaks to research on the gendered impact of trade agreements, particularly in women’s employment. The chapter is structured as follows. The first section reviews the literature regarding the economy as a gendered structure, its implication for trade policy, particularly for trade in services, and how Chile has included this topic in its PTAs. The second section presents some stylized facts on the evolution of women’s participation in the Chilean economy. In the third section, the methodological framework of analysis is discussed. The fourth section presents and discusses the chapter’s key results, which is that the inclusion of solid service provisions in PTAs could enhance the development of this sector and positively impact women’s employment. The results from the estimations suggest that the inclusion of deep service provisions in Chilean PTAs positively impacted women’s employment, particularly in the services sector. For men, the results showed a negative or nonsignificant effect. Finally, when analyzing the impact of these provisions on gender gaps, it shows that these agreements have contributed to reducing gender gaps in the workforce.

9.2 Gendered Impact of Trade Policy

9.2.1 Gender and Trade

While traditional theories of international and development economics do not directly address the existence of a gender-differentiated impact of economic and trade policies, it has become increasingly relevant to assess how these policies affect men and women differently. The “gender neutral” approach toward economics has been increasingly challenged (Elson Reference Elson1993; Benería Reference Benería1995). New theoretical and policy works highlight that human interactions are embedded in social contexts, dominated by norms and preconceptions leading to gender-based regimes. In this sense, there are social constructs related to gender, which foster segregation of jobs, division of labor, and differences in social positions in authority, among others (Ridgeway and Correll Reference Ridgeway and Correll2004).

The first challenges to traditional economic theories came from liberal feminist approaches toward international development, in which authors’ stated that the marginalized position of women in the economy could be explained due to their lower pay compared to men (Boserup Reference Boserup1970). Along these lines, they argued that including gender equality would reinforce the development processes, empowering the different stakeholders in the economy (Buvinic Reference Buvinic1976; Tinker and Bramsen Reference Tinker and Bramsen1976; Rogers Reference Rogers2005). As a gendered structure in the economy is recognized, heterodox approaches, such as basic needs theory, human capability theory, and ecofeminism theory, have also incorporated gender differences as a critical element in understanding socio-economic relationships. These theories have generated increased attention to the power relations within households and how this can affect labor issues, including women’s decision to participate in the workforce as well as the nature of that participation (Calasanti and Bailey Reference Calasanti and Bailey1991; Davies and Carrier Reference Davies and Carrier1999; Rai Reference Rai, Elias and Roberts2018).

For example, analyzing labor issues regarding the basic needsFootnote 1 approach often overlooks family power relations. However, human capability theory offers a comprehensive approach that includes legal, political, and human rights (Nussbaum and Sen Reference Nussbaum and Sen1993; Sen Reference Sen2001). The latter approach challenges the traditional view of the family, in which there is a common understanding and even distribution of tasks and activities. It highlights the impact of gender relations on women’s participation in the workforce. Ecofeminist theory takes this a step further in the context of sustainable development and advocates for an interdependent, anti-patriarchal model (Dreze and Sen Reference Dreze and Sen1990; Lahar Reference Lahar1991; Arriagada Reference Arriagada2002; Elias and Roberts Reference Elias and Roberts2018; Rai Reference Rai, Elias and Roberts2018). Theories on women and gender in development increasingly influence current economic perspectives. Gender equality is now a central topic, with an increasing focus on gender mainstreaming as the strategy to achieve it (Cáceres and Muñoz Reference Cáceres, Muñoz, Bahri, Remy and López2023b).

The underlying idea of gender approaches is that the economy functions as a “gendered structure” where both market and non-market activities impact its development (Ridgeway and Correll Reference Ridgeway and Correll2004; Ridgeway Reference Ridgeway2011; Rai Reference Rai, Elias and Roberts2018; Momsen Reference Momsen2019). Der Boghossian (Reference Der Boghossian2019) emphasizes that women experience unequal pay, underrepresentation, and barriers such as limited access to formal loans. The normative construction and division of responsibilities between men and women result in a division of paid and unpaid tasks that give way to an unequal distribution of resources and rewards in the economy. The context in which social relations are inscribed forms gender relations, conditioning the division of labor, differences within economic activities, and social authority, among others (Ridgeway and Correll Reference Ridgeway and Correll2004).

Likewise, it is essential to recognize that the differences in women’s access to resources – productive, financial, technology, and information – limits their ability to take advantage of gains from international trade and the possibility of expanding participation in domestic and international markets. In this way, understanding how social context affects gender relations permits the establishment of frameworks to empower women to benefit from the changes caused by international trade. This understanding will enable the formulation of public policies that promote the positive effects of international trade, strengthen women’s economic autonomy, and reduce existing gender inequalities (Bezanson and Luxton Reference Bezanson and Luxton2006; Rai and Waylen Reference Rai and Waylen2014). Therefore, promoting gender equality by increasing women’s participation in the economy is a common theme and strategy discussed by world leaders and development agencies.

International trade affects women and men differently depending on their economic positions as workers, traders, producers, consumers, etc. The roles assigned to women and men impact their economic autonomy, empowerment, and well-being. At the same time, various studies show that gender inequality affects the performance and competitiveness of economies (Juhn et al. Reference Juhn, Ujhelyi and Villegas-Sanchez2014; Audi and Ali Reference Audi and Ali2017; UNCTAD 2017; Bøler et al. Reference Bøler, Javorcik and Ulltveit-Moe2018; Kis-Katos et al. Reference Kis-Katos, Pieters and Sparrow2018; Nasser de Carvalho Reference Nasser de Carvalho2020; Sauvé Reference Sauvé2020). In this context, international trade has proven instrumental in promoting faster, sustainable economic development, as long as policymakers acknowledge the complex relationship between trade and gender and incorporate the necessary policies to guarantee even participation and distributional benefits. Gender-responsive trade policies can ultimately open new opportunities for women as employees and entrepreneurs (UNCTAD 2020).

In recent years, there has been increased attention to the gendered impact of trade policies (Keating Reference Keating2004; Gibb Reference Gibb2008; Frohmann Reference Frohmann2017), as well as increased interest in the inclusion of gender-sensitive provisions within trade agreements (Zarrill Reference Zarrilli2017; Bahri Reference Bahri2019, Reference Bahri2020; Cáceres et al. Reference Cáceres, Muñoz, Alarcón, Chávez, Fierro, Guzmán and Rogaler2021; Laperle-Forget Reference Laperle-Forget2022). Although the literature on the links between gender inequalities and trade is not conclusive, it has been determined that increasing the participation of women in economic activities can help reduce poverty and increase their income levels. This is because women’s participation leads to higher levels of economic activity and economic autonomy (Novta and Wong Reference Novta and Wong2017; WTO 2017b; CEPAL 2021). The literature has begun to analyze the impacts of trade policies on gender gaps, paying particular attention to their impact on poverty, wage differences, and feminized economic sectors (Çagatay Reference Çagatay2001; Fontana Reference Fontana, Bussolo and Hoyos2009). In particular, it is recognized that high levels of gender inequality are associated with countries with less commercial intensity and diversification (Kazandjian et al. Reference Kazandjian, Kolovich, Kochhar and Newiak2019). Using data on employment and wages, various authors have studied how trade liberalization can reduce the gap in employment participation, or wages, between men and women by strengthening sectors that are intensive in female labor or by expanding demand for work in the economy (Berik et al. Reference Berik, van der Meulen and Zveglich2004; Arndt et al. Reference Arndt, Robinson and Tarp2006; Villalobos and Grossman Reference Villalobos and Grossman2008; Menon and Van der Meulen Rodgers Reference Menon and Van der Meulen Rodgers2009).

In the 1990s, PTAs began progressively incorporating gender-related provisions through general provisions, specific chapters, and gender mainstreaming. The first references to the relationship between gender and trade in PTAs can be found in the instruments linked to labor issues and eliminating discrimination between men and women in workplaces and equal pay (Monteiro Reference Monteiro2018). The first chapter on trade and gender contained in a PTA – worldwide – was included in the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Chile and Uruguay in 2017. From here, the literature has focused on the analysis of the incorporation of gender in other preferential agreements and regional integration processes (López and Muñoz Reference López and Muñoz2018; López et al. Reference López, Muñoz and Cáceres2019; Cáceres et al. Reference Cáceres, Muñoz, Alarcón, Chávez, Fierro, Guzmán and Rogaler2021).Footnote 2

The year 2017 also marked a turning point in incorporating gender issues in the World Trade Organization (WTO). In December, at the 11th WTO Ministerial Conference held in Buenos Aires, Argentina, 118 members and observers supported the Buenos Aires Declaration on women and trade to eliminate obstacles to women’s economic empowerment (WTO 2017a). The declaration is based on the gender and trade chapters contained in Chile’s agreements with Uruguay and Canada. It follows what is expressed in goal 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Although the incorporation of the gender perspective has been slow at the multilateral level, mainly due to the complexity of reaching consensus, notable advances have been seen at a preferential level in the past decade.

9.2.2 Gender and Trade in Services

There is consensus that services have contributed to economic development as inputs to other productive activities and end-user consumption (Cali et al. Reference Cali, Elis and Willem2008; Francois and Hoekman Reference Francois and Hoekman2010; UNCTAD 2010). Therefore, they have become integral to trade policymaking, particularly negotiating PTAs. Trade in services faces barriers that differ from trade in goods (Borchert et al. Reference Borchert, Gootiiz and Mattoo2013; Benz and Jaax Reference Benz and Jaax2022). Specifically, because services are intangible, they do not need to cross borders physically, nor are they observable before purchase or physically storable, and their production and consumption typically occur in the same location. Thus, barriers to trade in services differ from those to goods, as they are not typically imposed on the border but rather at the domestic level. For this reason, services-related provisions do not have the same structure or impact as provisions for goods (Hoekman Reference Hoekman2006; Francois and Hoekman Reference Francois and Hoekman2010). Because of this, service commitments in international agreements do not involve tariff reductions but aim to consolidate countries’ policies and regulations vis-à-vis services.

Nevertheless, these agreements anchor openness and provide clear frameworks for developing the services sector for the benefit of domestic and foreign providers of services. In recent years, following the increasing mainstreaming of a gender perspective within trade policy, the literature has analyzed how trade in services impacts men and women differentially. Sauvé (Reference Sauvé2020) points out that services could become a source of inclusive growth, particularly when looking into the skills and job positions that women may hold. A robust services sector could enhance women’s participation in the workforce. Using data from India, Johannesson and Nordås (Reference Johannesson and Nordås2021) found that services sectors had lower wage gaps than those related to manufacturing. Furthermore, expanding services trade reduces wage gaps, contributing to more inclusive economic growth and development.

In the past decades, Chile has built an extensive network of PTAs to guarantee market access for its main export products and expand and diversify its export basket (López and Muñoz Reference López and Muñoz2015; Albertoni et al. Reference Albertoni, López, Montt, Muñoz, Rebolledo, Cornick, Frieden, Mesquitao and Stein2022). Within this strategy, services have been identified as a sector where the country could specialize, moving away from primary commodities linked to mineral extraction and agriculture. For this purpose, Chile has included services as a pillar of its trade negotiation mandates. While some commitments were made during the Uruguay Round in the context of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), Chile was not an active participant in multilateral service negotiations. Instead, the inclusion of services as an important issue within the negotiation mandates of Chilean trade agreements began in the mid-1990s when the country was pursuing its failed incorporation into the North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA). This process led to the first negotiations for a comprehensive FTA with Canada and Mexico, including topics beyond market access for goods, such as services, intellectual property, and investment (Muñozet al. Reference Muñoz, Cáceres and Rojas2021). By December 2022, out of thirty-three agreements signed by Chile, twenty-three include service provisions (SUBREI 2022).

Some common characteristics can be described when looking into the services-related content of Chilean PTAs. First, Chile has included these provisions in dedicated chapters on cross-border services. They have been complemented by specific chapters for sectors and topics such as telecommunications, financial services, transport services, movement of natural persons, and e-commerce. Mode 3 (commercial presence) is covered by chapters dedicated to investment.Footnote 3 While all chapters follow the same structure and include standard provisions and definitions, the main difference is using positive or negative list approaches (Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Cáceres and Rojas2021). When comparing Chilean agreements to others using data from the design of trade agreements (DESTA) project (Dür et al. Reference Dür, Baccini and Elsig2014), Chilean PTAs stand out regarding their degree of commitment and levels of liberalization. The country’s PTAs contain the main elements that characterize deep services integration, including references to GATS, national treatment and most favored nation provisions, sectorial provisions, and a relatively low number of excluded sectors.

It is recognized that an important element regarding service provisions in trade agreements is that beyond the additional liberalization achieved through these instruments, they bound economies’ existing policies (Findlay et al. Reference Findlay, Stephenson, Prieto, Macrory, Appleton and Plummer2005; Hoekman and Mattoo Reference Hoekman and Mattoo2013), which signal economies trajectories and reinforce reforms that may have been adopted unilaterally. Moreover, the agreements following negative list approaches tend to liberalize all service trade except sensitive areas, including specific sectors or modes of provisions (especially Mode 4).Footnote 4 Chile made significant efforts to liberalize its services sector starting in the early 2000s. The openness of Chile’s services sector was mainly bound in the first agreements signed during the early 2000s, particularly in the FTA with the United States. Since the subscription of this agreement in 2003, Chile has used it as a template for upcoming negotiations, following its structure and trade liberalization commitments, being recognized as a landmark concerning services liberalization. While some liberalization has been achieved in the latter agreements, we should not expect a huge effect at the margin with each additional PTA. However, the net effect of all these PTAs is potentially quite profound. Finally, while the objective to diversify the Chilean export basket has not achieved the expected results (López et al. Reference López, Muñoz, Mulder, Fernández-Stark and Álvarez2020; López and Muñoz Reference López, Muñoz, Mulder, Fernández-Stark and Álvarez2020; Prieto et al. Reference Prieto, Sáez, Goswami and Sáez2011), it is believed that the inclusion of service provisions within trade agreements may have helped to foster the participation of women in the economy, as men could have moved toward other economic activities and the expansion of domestic services.

9.3 Female Labor Participation in Chile: Stylized Facts

While the previous section reviewed the incorporation of service provisions within Chilean PTAs, this section presents some stylized facts regarding the participation of women in the Chilean workforce. This section mainly investigates the involvement of women in the services sector and the evolution of the participation gender gaps in the country. Data from other Latin American countries are included as a comparative basis of analysis. The studied period comprises thirty-two years, from 1990 until 2021, covering all democratic governments following the military dictatorship in Chile and the period in which most preferential trade liberalization took place (López and Muñoz Reference López and Muñoz2015).

Despite decades of sustained economic growth and poverty reduction, Chile has been described as an unequal country in terms of income and wealth (Contreras Reference Contreras2003; Contreras and Ffrench-Davis Reference Contreras and Ffrench-Davis2012; Mieres Brevis Reference Mieres Brevis2020). The roots of inequality in the country may be explained by factors such as income disparities, uneven capital accumulation, educational gaps, social networks, and access to social services and infrastructure, amongst others (Núñez and Tartakowsky Reference Núñez and Tartakowsky2011; Contreras et al. Reference Contreras, Otero, Díaz and Suárez2019; Flores et al. Reference Flores, Sanhueza, Atria and Mayer2020; Gutiérrez and Muñoz Reference Gutiérrez and Muñoz2022). Furthermore, this inequality affects indigenous populations and women most, particularly when reviewing income disparities (Agostini et al. Reference Agostini, Brown and Roman2010; Gammage et al. Reference Gammage, Alburquerque and Durán2014; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez, Bértola and Williamson2017). One cause of this difference may be explained by the uneven participation of women in the formal workforce (Undurraga Reference Undurraga2011; Ipsen Reference Ipsen2022).

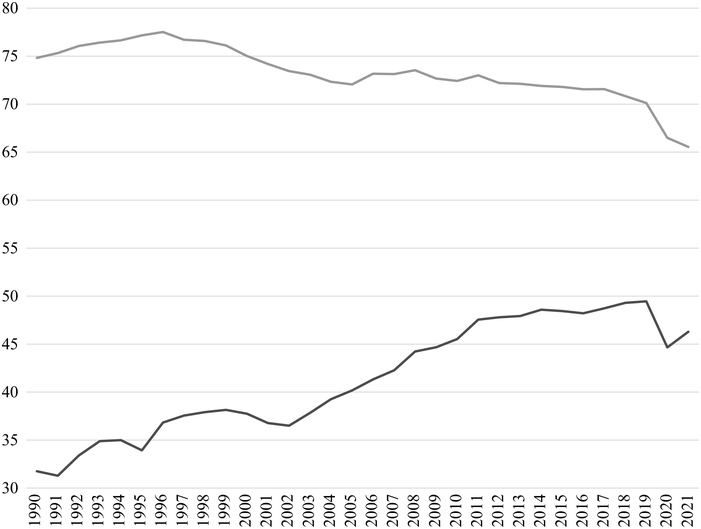

As shown in Figure 9.1, Chile’s female workforce participation is one of the lowest in the world (Contreras and Plaza Reference Contreras and Plaza2007; Rau Reference Rau2010). Since 1990, men’s participation in the labor force has stayed at over 70 percent, except during the COVID-19 crisis, which dropped to 65 percent in 2021. On the contrary, women’s participation has never surpassed the 50 percent threshold. In the early 1990s, women’s participation in the labor force was only 31 percent, slowly increasing to 37 percent by the end of that decade. The commodity boom of the 2000s created rapid growth in the women’s labor force (Ocampo Reference Ocampo2008), which grew over 10 percent in a decade, reaching maximum participation of 49.5 percent in 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic. As social and economic activity restrictions were enacted to control the COVID-19 pandemic, these policies profoundly impacted labor participation.

This impact was uneven between genders (Arteaga-Aguirre et al. Reference Arteaga-Aguirre, Cabezas-Cartagena and Ramírez-Cid2021; Velasco Reference Velasco2021). While men’s participation in the labor force dropped by four percentage points, representing a 5.7 percent reduction, for women participation decreased by five percentage points, representing a 10 percent overall reduction. Hence, both the absolute and relative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on men’s and women’s work participation was stronger for women than men, increasing the gaps between both groups.

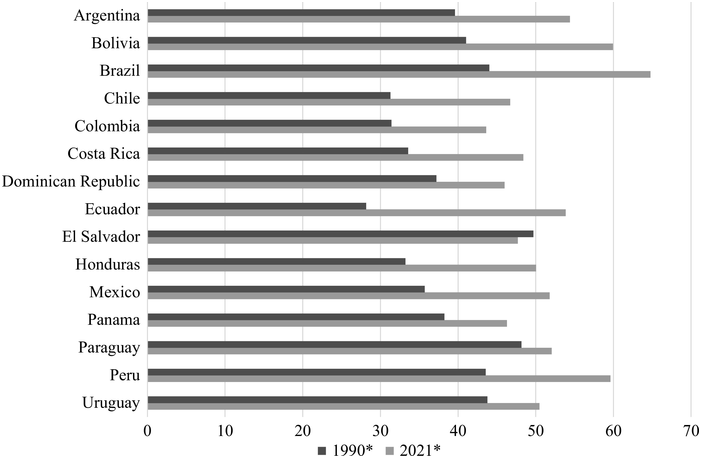

Participation of women in the workforce in Chile is among the lowest in Latin America. As shown in Figure 9.2, in 1990, Chilean women’s participation in the workforce was the second lowest (31.2 percent), only topped by Ecuador (28,1 percent), but a total fifteen percentage points lower than El Salvador, which had the highest participation rate (49.6 percent). In thirty-two years, between 1990 and 2021, women’s participation grew in all Latin American economies. In the case of Chile, women’s participation rate rose to 46.7 percent but still ranks among the lowest in the region. For example, Brazil’s rose from 44 percent to 64.7 percent, currently making it the region’s highest. During this period many countries – including Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Argentina, Ecuador, Paraguay, Mexico, Uruguay, and Honduras – passed the 50 percent threshold. Chile and countries such as Colombia, Panama, and the Dominican Republic still have participation rates of less than 50 percent. Nevertheless, it must be stated that the figures reflect the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, which reduced women’s participation in the workforce throughout the region. However, this does not change that Chile still has a gap in women’s participation vis-à-vis other Latin American economies.

Figure 9.2 Women’s participation in the workforce. Selected Latin American economies (ILO estimates). 1990/2021*

Note: *Data for Bolivia, Dominic Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, and Uruguay correspond to 2020.

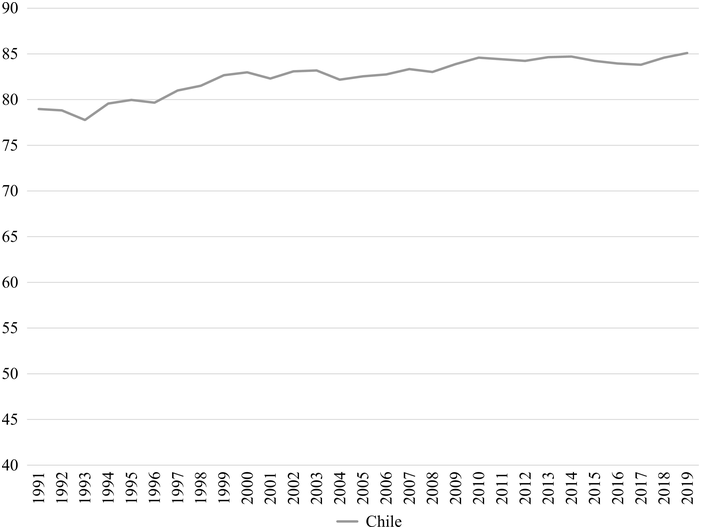

Concerning the participation of women in the services sector, Figure 9.3 shows that most women in the workforce in Chile, approximately 85.1 percent in 2019, are employed in the services sector. This information reflects the gendered structure of the overall economy, as most women are expected to engage in domestic and care activities and, therefore, do not participate prominently in industrial activities. Their participation in agricultural activities is mainly linked with subsistence and familiar agriculture or informal activities such as harvesting during spring and summer.

Figure 9.3 Women’s participation in the services sector, as a share of total women’s employment. Chile. 1991–2019.

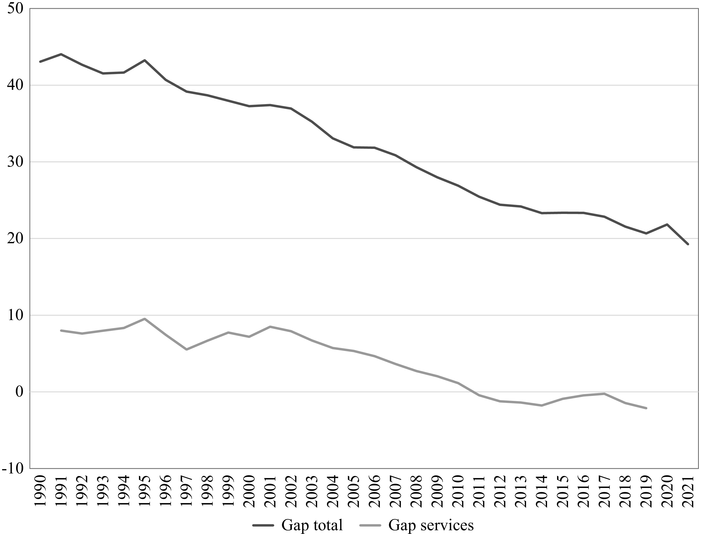

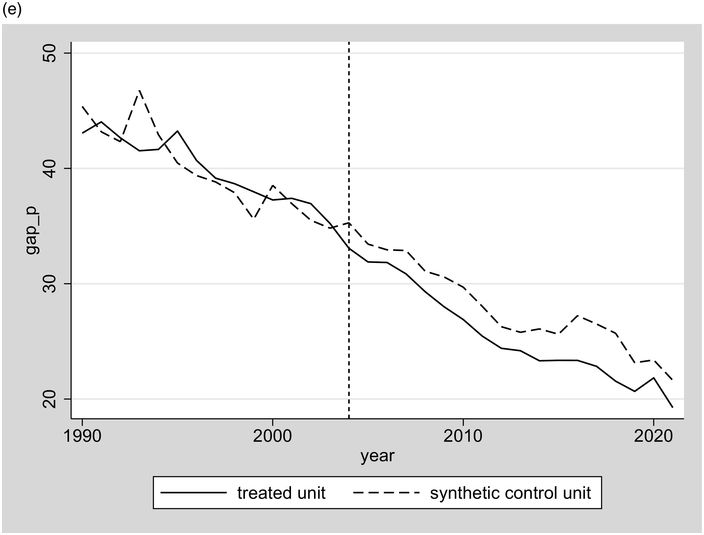

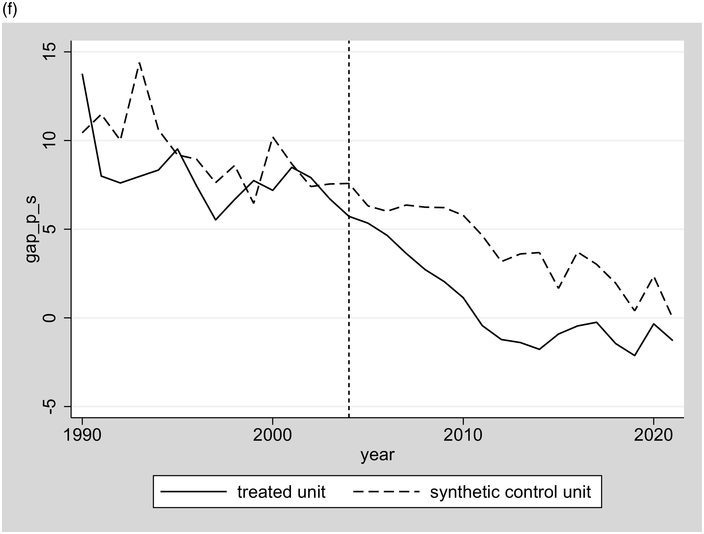

Although the increased participation of women in the Chilean workforce has reduced the gender gap in the labor force in the Chilean labor market, the gap continues to be among the highest in the Latin American region. As shown in Figure 9.4, the total workforce gender gap (the rate of men participating in the labor market compared to women) has decreased from over 40 percent in the first years of the 1990s to almost 20 percent by the end of 2021. Within the services sector, there was a ten-point gender gap at the beginning of the 1990s, but parity was achieved in the early 2010s. Since then, the gap has fluctuated within two points for men and women, which reflects normal year-to-year variations.

Figure 9.4 Gaps in women’s and men’s labor participation (total and services). 1990–2021.

9.4 Theoretical Assumptions and Hypothesis

The theoretical assumption that expanded trade in services may increase women’s labor participation is grounded in the understanding of the unique characteristics of the service sector and its alignment with the existing skill sets and employment preferences of women. Traditionally, the service industry has been considered more inclusive and flexible, often offering part-time, remote, or flexible working arrangements that appeal to women who may juggle work with family responsibilities (Steiger and Wardell Reference Steiger and Wardell1995; Leschke Reference Leschke, Eichhorst and Marx2015; Stichter Reference Stichter, McDowell and Sharp2016). As global trade in services grows, driven by technological advancements and the increasing digitization of many service roles, new opportunities arise for women to engage in the workforce (Krieger-Boden and Sorgner Reference Krieger-Boden and Sorgner2018; Larsson and Viitaoja Reference Larsson, Viitaoja, Larsson and Teigland2019; Charles et al. Reference Charles, Xia and Coutts2022). One of the main characteristics of services and digital trade is that this expansion may not be limited by geographical boundaries (as it happens for goods), allowing women to participate in the global economy from their local environments. The growth in service trade could potentially lead to a higher demand for new skills, resulting in increased employment opportunities for women. This alternative, in turn, can contribute to greater economic independence and empowerment for women, further promoting gender equality in the workforce (Foley and Cooper Reference Foley and Cooper2021; Parmer Reference Parmer2021). However, it is important to note that this positive outcome is contingent on supportive policies and frameworks that ensure fair employment practices and address any gender biases in the workplace.

Moreover, trade agreements that specifically encompass services can significantly influence the job market by creating new opportunities and setting the standards for labor practices. Including services-related provisions within these agreements may lead to a surge in demand for service-oriented jobs, many of which align closely with the sectors where women traditionally have a stronger presence or competitive advantage. For instance, women have historically played a dominant role in sectors like healthcare and education. The liberalization of these services through trade agreements can lead to a proliferation of jobs in these sectors, potentially increasing employment opportunities for women.

PTAs can also include provisions directly addressing gender-related issues (Bahri Reference Bahri2019; López et al. Reference López, Muñoz and Cáceres2019; Cáceres and Muñoz Reference Cáceres, Muñoz, Bahri, Remy and López2023b). These might involve encouraging gender equality in the workplace, promoting women’s entrepreneurship, and ensuring equitable treatment in employment. This approach can create an enabling environment that increases women’s participation in the labor force and enhances their status within it. However, it is crucial to recognize that the positive impacts of trade agreements on women’s labor participation are not automatic. They depend significantly on how these agreements are structured and implemented. A conscious effort must be made to ensure these agreements are inclusive and consider the unique challenges and barriers women face in the workforce. This effort includes addressing wage gaps, supporting skill development, and ensuring access to necessary resources and technology. With thoughtful implementation, trade agreements that include services have the potential to be a powerful tool in promoting gender equality and empowering women economically.

From here, this chapter aims to understand the impact of PTAs on women’s labor participation, particularly those with service provisions. Using Chile as a case study, due to its long-lasting trade policy openness and relatively low female participation in the workforce, the following working hypotheses are stated:

H1: The subscription of PTAs with deep service commitments might increase women’s labor force participation in Chile.

9.5 Methodological Approach and Dataset

Having outlined the theoretical basis of our research and reviewed the main trends of women’s participation in Chile’s labor market, this section briefly presents our methodological approach. Following the literature (Sauré and Zoabi Reference Sauré and Zoabi2014; Gaddis and Pieters Reference Gaddis and Pieters2017; Rocha and Winkler, Reference Rocha and Winkler2019), the chapter proposes the following model specification to capture the impact of including deep services commitments in Chilean PTAs on female labor participation and workforce gender gaps:

where k indicates country and t periods (years). The dependent variable ![]() is set to describe female labor participation or gender gaps in the workforce. The model specification presented in equation (9.1) proposes both trade (

is set to describe female labor participation or gender gaps in the workforce. The model specification presented in equation (9.1) proposes both trade (![]() ) and country-specific x (

) and country-specific x (![]() ) control variables. Two parameters of interest are included as explanatory variables: a dummy variable to capture the existence of a PTA covering deep service provisions (D_ser), taking value 1 for those countries having PTA with deep service provisions in force in year t, and an interaction variable identifying those provisions for the case of Chile (I_ser_cl), so to have a differentiated effect for this country. These variables are constructed from revising PTAs using existing coding datasets and the authors’ analysis and classification of commitments (Dür et al. Reference Dür, Baccini and Elsig2014; Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Cáceres and Rojas2021). Hence, it is said that a PTA includes deep services provisions if the commitments covered by the agreement include references to GATS, national treatment and most favored nation provisions, sectorial provisions, and a relatively low number of excluded sectors. The latter variable intends to capture the impact of these provisions on Chilean labor force participation to correctly assess the effect on women’s involvement in the country.

) control variables. Two parameters of interest are included as explanatory variables: a dummy variable to capture the existence of a PTA covering deep service provisions (D_ser), taking value 1 for those countries having PTA with deep service provisions in force in year t, and an interaction variable identifying those provisions for the case of Chile (I_ser_cl), so to have a differentiated effect for this country. These variables are constructed from revising PTAs using existing coding datasets and the authors’ analysis and classification of commitments (Dür et al. Reference Dür, Baccini and Elsig2014; Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Cáceres and Rojas2021). Hence, it is said that a PTA includes deep services provisions if the commitments covered by the agreement include references to GATS, national treatment and most favored nation provisions, sectorial provisions, and a relatively low number of excluded sectors. The latter variable intends to capture the impact of these provisions on Chilean labor force participation to correctly assess the effect on women’s involvement in the country.

Therefore, equation (1) can be restated as follows:

where ![]() represents the dependent variable, for which six specifications have been selected and constructed using information from the World Bank and the International Labor Organization statistical datasets. First, the ratio of women’s labor participation (wom_par) and participation in the services sector (wom_par_s) are included. Both indicators were chosen due to gendered structures; women tend to participate more actively in the services sector. Second, to test whether there are differentiated impacts between men and women, the same indicators for men are included (men_par and men_par_s, respectively). Finally, differential participation indicators are included to observe gaps between men and women in the workforce and the services sector (gap and gap_ser, respectively). In addition to the chapter’s parameters of interest, as control variables, equation (9.2) includes the natural logarithm of the country’s k GDP in year t (

represents the dependent variable, for which six specifications have been selected and constructed using information from the World Bank and the International Labor Organization statistical datasets. First, the ratio of women’s labor participation (wom_par) and participation in the services sector (wom_par_s) are included. Both indicators were chosen due to gendered structures; women tend to participate more actively in the services sector. Second, to test whether there are differentiated impacts between men and women, the same indicators for men are included (men_par and men_par_s, respectively). Finally, differential participation indicators are included to observe gaps between men and women in the workforce and the services sector (gap and gap_ser, respectively). In addition to the chapter’s parameters of interest, as control variables, equation (9.2) includes the natural logarithm of the country’s k GDP in year t (![]() , the share of services in their gross domestic value added (

, the share of services in their gross domestic value added (![]() ), and the value of export services (

), and the value of export services (![]() ) extracted from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators dataset.

) extracted from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators dataset.

Having set the model to be estimated, to test the chapter’s hypotheses, a panel dataset comprising seventeen countries in Latin America was built for the period 1990 to 2021. The sample selection was based on an ad hoc selection of control countries that matched with observable and unobservable similarities to the country under study, Chile. Economic and export structures, economic cycles, and women’s participation in economic activity were the most important factors. From here, it is shown that Latin American economies have faced similar economic development processes (Hofman Reference Hofman2000; Bértola and Ocampo Reference Bértola and Ocampo2012), and particularly those in South America have similar trade patterns, with a high dependency on the export of natural resources, including mineral and agriculturally based commodities (Cypher Reference Cypher2010; Svampa Reference Svampa2013; Giraudo Reference Giraudo2020). Following the crisis in the decade of 1980s, various countries in the region have followed an active integration process, including the signing of PTAs with regional and overseas partners (Agosin and Ffrench-Davis Reference Agosin and Ffrench-Davis1993; Choksi et al. Reference Choksi, Michaely, Papageorgiou, Köves and Marer2019; Cornick et al. Reference Cornick, Frieden, Mesquita Moreira and Stein2020). Finally, while Chile has a lower share of female participation in the region’s labor force, Latin America’s countries share substantial gender inequalities, including access to the formal labor market (Costa et al. Reference Costa, Silva and Vaz2009; Alonso Reference Alonso2020).

9.6 Results and Discussions

A generalized least square regression was used to estimate the value of the coefficients associated with the control parameters, considering the nature of the data. Table 9.1 shows the results for the six specifications of the dependent variable. The first model uses women’s participation in the workforce as a dependent variable, aiming to understand how services PTAs may impact the participation of women in the various economic activities of the countries. First, we may point out that, while positive as expected, coefficients associated with GDP and services exports are not statistically significant. This result presents some challenges in its interpretation, as it would be expected that a higher economic activity could be linked to an increased participation of women in the workforce. A possible explanation for this may be the selected pool of countries (i.e., Latin American economies), in which for relatively smaller economies, women tend to have higher participation in employment due to being the sole contributor to their households, and many times in informal activities which are not well registered.

| Dep. var. | Women part. | Women part. in services | Men part. | Men part. in services | Gap labor part. | Gap services part. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural logarithm GDP | 1.13 (0.23) | 0.98 (0.160) | 0.759 (0.142) | 3.179*** (0.000) | −1.33 (0.182) | 1.313** (0.040) |

| Service value added | −0.18*** (0.004) | −0.25 (0.60) | −0.17*** (0.000) | 0.07** (0.021) | 0.004 (0.935) | 0.113** (0.012) |

| Services exports | 0.90 (0.228) | 1.28** (0.02) | 0.524 (-0.069) | 0.278 (0.471) | −0.619 (0.376) | −0.751 (0.145) |

| Dummy services | −0.36 (0.649) | −0.98* (0.09) | 0.037 (0.905) | −0.225 (0.568) | 0.483 (0.508) | 0.673 (0.221) |

| Interaction dummy services Chile | 0.10** (0.041) | 0.07** (0.047) | −0.034* (0.078) | -0.020 (0.421) | −0.142*** (0.002) | −0.94*** (0.007) |

| Trend | 0.29*** (0.000) | 0.31*** (0.000) | −0.197*** (0.000) | 0.052* (0.068) | −0.438*** (0.000) | −0.251*** (0.000) |

| R2 | 0.1264 | 0.3570 | 0.029 | 0.3716 | 0.2893 | 0.2163 |

| Obs. | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 |

| Groups | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

Note: Standard deviation in parenthesis. * 10 percent significance; ** 5 percent significance; *** 1 percent significance.

On the other hand, the coefficient associated with the share of services in the economy’s value added is negative and statistically significant. This result may be counterintuitive, as a higher share of services in the economy would imply a higher use of labor, and normally the service economy is a sector in which women have relatively higher participation. When one looks into the parameters of interest, it is noted that the dummy variable associated with agreements with strong service provisions is negative and non-statistically significant. This parameter would imply that lower participation of women in the workforce would be expected for those economies subscribing to a PTA with service provisions. Nevertheless, as shown, the hypothesis that the parameter’s value is zero cannot be rejected. Moreover, when looking specifically into the case of Chile, the main case study of this chapter, the value of the parameter associated with the country’s interaction term with services PTA shows a positive and statistically significant relationship. Hence, the data suggest that the subscription of PTAs with strong service provisions for Chile has positively impacted women’s participation in the workforce. This result reinforces the chapter’s first working hypothesis, as the inclusion of service provisions in PTA would increase the participation of women in the workforce, as shown for Chile. This could be explained by the expansion of tradable sectors’ activity and the overall economic growth associated with these agreements, which have implicated an increase in the demand for productive factors, including labor.

The second model specification uses the participation of women in the services sector as a dependent variable, as the inclusion of deep service provisions in PTA should positively impact the development of this sector in signatory countries and, therefore, expand the participation of women in this market. The estimation shows that GDP (positive coefficient) and the share of services in the economy (negative coefficient) are not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the export of services is positive and statistically significant, with an associated coefficient of 1.28, meaning that an increase in 1 percent of services exports would be associated with a 1.28-point increase in women’s participation in the services sector. This result is interesting, as it may show a link between the development of a more robust export services sector and the increased participation of women in this sector’s workforce. The interpretation of the coefficients associated with the variables of interest shows that, while the inclusion of service provisions would be linked with lower participation of women in the services sector for other countries, this would be the opposite for Chile. The service dummy’s result suggested that including deep service provisions in PTA would reinforce this sector and, therefore, increase demand for productive factors, including women’s labor. This alternative is suggested for Chile’s case. On the one hand, these results can be explained by the fact that the sample may present in terms of economic output and the subscription of PTAs, as the smaller economies in the sample have subscribed to PTAs. In contrast, countries such as Argentina or Brazil – the biggest economies in the sample – have not engaged in these agreements. Besides, the econometric specification could be over-representing lagged results. An AR(1) model is estimated below to overcome the second hypothesis.

The third and fourth models replicate the previous analysis, using men’s participation in the labor market and the services sector, respectively. For the participation of men in the labor market, results are equivalent to those for women, except for the interaction term for Chilean PTAs, which is negative and statistically significant. This result, while counterintuitive, can be explained due to the high participation rate of men in the economy before signing these agreements. In the 1990s, Chile’s economy grew by double digits, expanding the demand for various productive factors, including labor. In the decade of the 2000s, while the expansion of GDP continued, it was also accompanied by an increase in tertiary education enrollment and women’s participation. These factors may explain a relative drop in men from the workforce.

Nevertheless, it must be stated that the share of men participating in the workforce continues to be higher than that of women, for which this decrease associated with the subscription of PTA may not be interpreted as an overall decrease in work participation but a relatively smaller increase for women. Finally, the fifth and sixth models are particularly interesting, as they reflect the changes in gender gaps in labor market participation. For both models, the coefficient associated with Chile’s subscription of PTAs with deep service provisions (Interaction dummy services Chile) shows a negative and significant value. These values, representing a reduction in the gap between men and women, reaffirm the hypothesis that these agreements have been functional in reducing gender disparities as they expand women’s participation in the workforce, both in general and in the services sector.

The presence of an autoregressive model can be one of the main problems with econometric estimations based on panel data. This may be the case when the model’s past values predict future values, which can be stated for various economic variables – particularly those related to labor markets – as there are a series of determinants that do not allow for a quick change or that have little or no variation in their values (including the existence of contracts and inertia). As seen in Table 9.1, the Trend parameter is statistically significant for all specifications, suggesting an autoregressive model is present. For this reason, the equation (9.2) is rerun using a GLS with an autoregressive process, AR(1), in which the value of the actual observation is based on the immediate past one. Results of this second estimate are presented in Table 9.2 for the six specifications of the dependent variable. Overall, it can be stated that no significant changes are observed between both specifications, as most coefficients have values and statistical significance similar to the previous equations. The main difference in women’s participation in the labor force is that the coefficient associated with services exports is positive and highly significant under the new specification. The coefficient of interest, Interaction dummy services Chile, continues to be positive and statistically significant, reinforcing the hypothesis that these agreements promote women’s participation in the Chilean labor market. Similar conclusions can be drawn regarding women’s participation in the services sector, with the positive and high significance of the parameters associated with services exports and Chilean PTAs.

| Dep. var. | Women part. | Women part. in services | Men part. | Men part. in services | Gap labor part. | Gap services part. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural logarithm GDP | 0.617 (0.564) | 0.630 (0.454) | −2.758*** (0.000) | 3.733*** (0.000) | −1.919 (0.092)* | 1.412** (0.045) |

| Service value added | −0.149* (0.077) | 0.025 (0.699) | −0.139*** (0.000) | 0.176*** (0.003) | −0.036 (0.651) | 0.052 (0.390) |

| Services exports | 3.528*** (0.000) | 3.950*** (0.000) | 2.151*** (0.000) | 1.537*** (0.006) | −4.193*** (0.000) | −2.446*** (0.000) |

| Dummy services | 0.807 (0.403) | 0.521 (0.490) | −0.593 (0.103) | 0.387 (0.553) | −1.378 (0.128) | −0.742 (0.292) |

| Interaction dummy services Chile | 0.126* (0.067) | 0.117** (0.031) | −0.067* (0.079) | 0.042 (0.422) | −0.196*** (0.002) | −0.126** (0.014) |

| R2 | 0.3153 | 0.3153 | 0.0137 | 0.4929 | 0.4808 | 0.2387 |

| Obs. | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 | 537 |

| Groups | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

Note: St. dev. in parenthesis. * 10 percent significance; ** 5 percent significance; *** 1 percent significance.

When one looks into men’s participation, the main conclusion is that service exports positively impact men’s participation, and the inclusion of deep service provisions in trade agreements has a negative effect on men’s workforce participation and is nonsignificant for the services sector. More notable results are found when analyzing gender gaps in labor participation. On the one hand, services exports have a largely negative and significant coefficient for the total labor and services sector. This result would reinforce the idea that the higher the export of services, the lower the gender gaps in the labor market would be observed, as higher demand for productive resources would lead to a more egalitarian participation of men and women in the economy. The same conclusion can be drawn for a parameter associated with Chilean PTAs with deep service provisions, as both specifications show a negative and statistically significant coefficient. Overall, the results support the chapter’s hypotheses, as the coefficients associated with Chilean PTAs positively impact women’s participation and negatively impact gender gaps. Therefore, it could be concluded that these agreements foster the development of the services sector, enhance the participation of women, and help reduce gender disparities.

9.6.1 Robustness Checks

Two alternative methodologies are presented below to check the robustness of the previously shown results. First, to eliminate possible unobservable country-fixed effects that may impact the estimations, the first differences of the variables were taken, such that the model presented in equation (9.2) can be rewritten as:

where the subscript s denotes the change within periods t – t −1; results for this alternative specification are shown in Table 9.3 for the variable of interest (Interaction dummy services Chile). While not all parameters are reported, it can be stated that, except for the coefficient associated with participation in the services sector gap, all results are statistically significant. When looking at women’s participation in the workforce and the services sector, the existence of PTAs with deep service provisions is associated with a substantial increase in women’s labor participation in Chile. While this is not looking directly into economic growth, these findings may support the hypothesis that these agreements foster economic development, as they show that they may increase women’s participation in the workforce. Particularly in a country such as Chile, where men’s participation in the workforce was already high before the signing of these agreements, the potential to grow in the services economy is mainly related to creating opportunities for women to occupy jobs in the services sector.

Women part. | Women part. in services | Men part. | Men part. in services | Gap labor part. | Gap services part. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction dummy services Chile (1 vs 0) | 3.534*** (0.950) | 2.706** (0.997) | −0.922* (0.510) | −1.972** (0.790) | −1.189** (0.503) | −0.455 (0.285) |

Note: St. dev. in parenthesis. * 10 percent significance; ** 5 percent significance; *** 1 percent significance; ATET estimate adjusted for covariates, panel effects, and time effects.

In contrast, the results given in Table 9.3 show that the existence of PTAs with deep service sector provisions is associated with a reduction in men’s labor force. This result may be counterintuitive, as agreements should increase labor participation. To account for this phenomenon, two explanations are presented. First, during the 1990s, the Chilean economy was overheating, for which the labor market in the 2000s was adjusting, increasing the share of the population acceding to formal tertiary education instead of joining the workforce after high school. Second, the increasing participation of women in the economy, particularly in the services sectors, has begun to level the field. While there is still a profound participation gap in the overall workforce, this has been reduced in the services sector. These explanations are consistent with the results of the final two specifications, in which signing PTAs with deep service provisions reduces the overall gap in labor markets. In contrast, this effect is statistically nonsignificant for the services sector, as the gap between men and women is lower in this sector. Nevertheless, the services sector comprises various activities, and it may be pointed out that women are still mainly employed in domestic, reproductive, and care jobs. For this, a detailed analysis of the subsectors in which men and women are employed within the services sectors could bring additional light to reducing gender gaps in the economy.

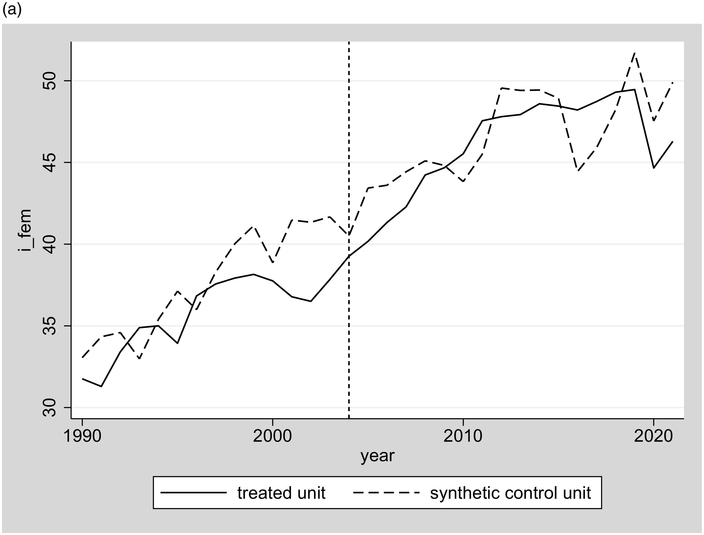

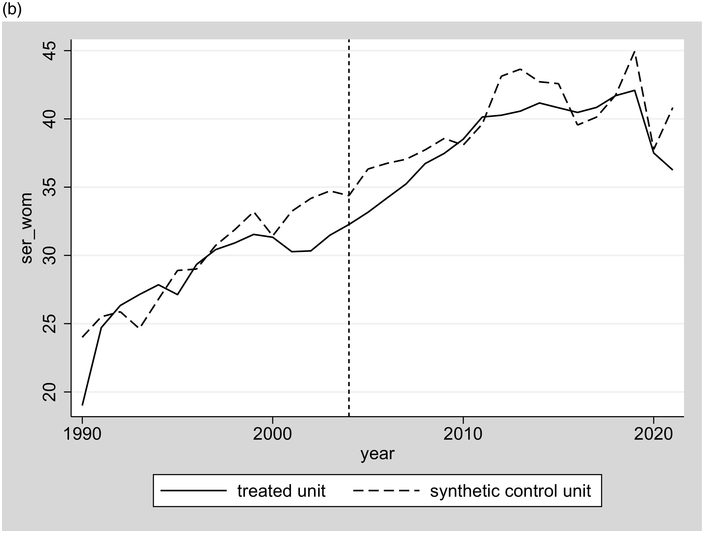

A second method used as a robustness check for this chapter is a synthetic control method (SCM). The SCM is proposed as an alternative method to estimate the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable. This method relies on constructing a synthetic control of the outcome variable to compare pretreatment and aftertreatment results (Abadie et al. Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2010; Billmeier and Nannicini Reference Billmeier and Nannicini2013; López et al. Reference López, Muñoz and Cáceres2022). Based on the database built for the estimations, a synthetic Chile was constructed from countries that have not signed PTAs with strong service provisions. As for determining the treatment year, the Chile–United States agreement has been identified as a milestone for its structure, extent, and policy implications. Therefore, the year 2003 is used as a threshold. Figure 9.5 presents the results for the SCM for the six specifications of the dependent variable. The first two graphs (Figures 9.5a and 9.5b) show the results for women’s participation in the workforce and women’s participation in the workforce of the services sector. The SCM is inconclusive regarding the difference between the treated and non-treated units in these two scenarios. In both cases, a positive trend can be observed throughout the studied period, including the decrease caused by the COVID-19 pandemic at the end of the series. While this result does not suggest a significant impact of PTAs, it is still positive and does not rule out previous conclusions.

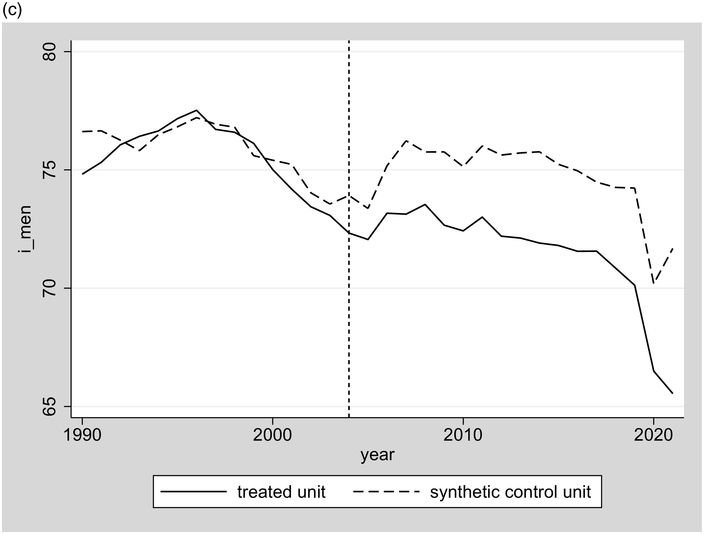

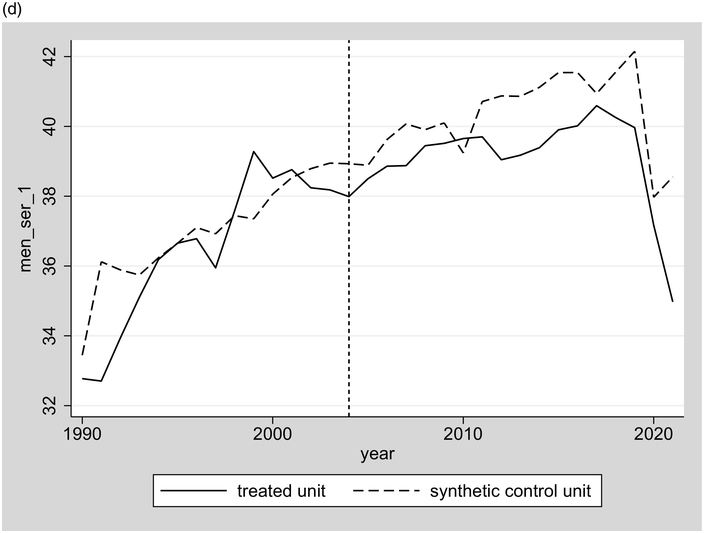

Moreover, from an examination of the following graphs (Figures 9.5c and 9.5d), it can be stated that for men’s participation, there is indeed a negative impact on their labor participation, as suggested by previous methods. The values in the y-axis are scaled for each graph, for which the reduction of men’s participation oscillates between 65 percent and 80 percent, while for women, it was between 30 percent and 50 percent. This result is relevant because, for men, it can be stated that full occupation has been achieved. Not all men over fifteen years old are expected to be actively part of the workforce, as some may still be studying, retired, or taking care of domestic activities. The most interesting results are found in the specifications looking into gaps in the workforce.

Figures 9.5e and 9.5f show that the treated unit values are lower for overall labor and services sector participation. These values reinforce the hypothesis that PTAs with strong service provisions have positively impacted the reduction of gender gaps by fostering this sector and, through it, the participation of women in the economy. Furthermore, this effect can be understood as both the growth of women’s participation and the relative reduction of men’s participation. Both effects imply a decrease in the gender gap in Chilean labor markets.

9.7 Final Remarks

The uneven distribution of wealth and income between men and women is one of the main challenges of current economic policymaking. This is a long-lasting problem developed and developing economies pursuing sustainable development objectives face. To overcome this situation, understanding the economy as a gendered structure becomes a valuable tool to study the causes of inequalities and how different policies, amongst them trade policies, impact gender disparities.

The purpose of this chapter was to analyze how the inclusion of service provisions in PTAs affects the gendered structure of the economy in Chile. The working hypotheses that guided the research were that the inclusion of solid service provisions in PTAs might enhance the development of this sector and positively impact women’s employment. Hence, a more substantial impact of PTAs on women’s employment than on men’s should be encountered, which should help reduce the gender gaps in this sector. The estimations’ results suggest that including deep service provisions in Chilean PTAs positively impacted women’s employment, particularly in the services sector. For men, the results showed a negative or nonsignificant effect. Finally, when analyzing the impact of these provisions on gender gaps, it shows that these agreements have contributed to reducing gender gaps in the workforce.

These results reinforce the idea that strengthening the services sector allows for a relatively higher expansion of women’s employment compared to men, reducing gender gaps. Before signing the agreements, men in Chile already showed high labor participation, so there was less potential or scope for an increase in occupation. Therefore, women can benefit the most from the economic expansion resulting from trade agreements. This increased participation is the first step toward a more gender-balanced economy. It shows that trade policy can become instrumental in reducing gender gaps.

In a broader sense, the results reinforce the thesis that their impact beyond trade flows should be considered when analyzing PTAs. Following Dür et al. (Reference Dür, Baccini and Elsig2014), the design of these agreements extends into matters beyond trade, including the institutional organization of the economy in areas such as labor, environment, and competition policy. Therefore, a careful examination of their results in those issues should be considered, especially when governments’ objectives go far beyond the expansion of trade flows, and in which these flows are an instrument for promoting inclusive and sustainable development.

Nevertheless, it must be stated that the results of this chapter looked at aggregate data, for which new avenues of research need to be explored. First, even though female labor force participation increased in Chile, this does not mean that the gendered structure of economic activity has been completely dismantled. While women’s participation in the workforce increased, this participation is primarily within the services sector. We do not know if these jobs are concentrated around jobs linked to reproductive and care activities, which might reinforce traditional gender norms. Moreover, the services sector comprises high-value-added activities requiring specialized jobs and low-value-added activities in which employment is focused on low-skill positions. Therefore, increased participation in the services sector, per se, does not necessarily imply a better economic position. Second, the results only reflect workforce participation but not the remuneration of this participation.

Gender gaps are not reduced to participation but also wages and working conditions. Even though a more significant number of women participate in formal jobs, this does not necessarily imply that the salaries are similar, for which huge gaps could still be observed. Third, other related issues, such as domestic and unpaid work, are not considered within current statistics. Evidence suggests that women sacrifice their time in the workforce, as they still take care of most domestic and unpaid household activities. This situation leads to an uneven distribution of unpaid tasks and the prevalence of gender differences in time spent in remunerated and unpaid activities. So, while this chapter provides insights into the effects of trade agreements and service provisions on women’s labor participation, much more research is needed to understand the causes and consequences of gender disparities.

The chapter also opens new avenues for future research on how trade agreement design and implementation may become instrumental in achieving gender equity objectives. First, while the chapter looked into agreements with service provisions, it was stated that new PTAs are increasingly including gender-related provisions, either in general terms, as part of existing chapters, or even as new chapters in the agreements.Footnote 5 Hence, it may be necessary to understand if service chapters and service-related provisions may also benefit from a gender perspective and, if so, how existing commitments should be modified to meet gender equity objectives. Second, the chapter benefits from the case of Chile, which may be considered an outlier in terms of its trade policy. Therefore, new analysis covering other economies facing different challenges concerning their trade policies and gender structures may contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between trade policy, services, and gender equity. Third, in times of economic and political turmoil, getting to know the impacts of trade agreements beyond trade flows may allow us to extend the discussion on these international instruments. Moreover, it is likely that if PTAs are linked with the consecution of other objectives such as sustainability, environment protection, or gender equity, the general population may positively perceive them.