Refine search

Actions for selected content:

46 results

16 - Reading Wounds in Women’s Prison Writing

- from Part IV - Survivors

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to American Prison Writing and Mass Incarceration

- Published online:

- 02 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 October 2025, pp 261-274

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - The Sailor’s Daughter

-

- Book:

- Maritime Relations

- Published online:

- 23 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 September 2025, pp 140-181

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

- from Part III - The Downfall

-

- Book:

- The Generalissimo

- Published online:

- 31 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 229-234

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 34 - Biographers, Memoirists, and Reminiscers (1823–1878)

- from Part IV - Afterlives

-

-

- Book:

- Percy Shelley in Context

- Published online:

- 17 April 2025

- Print publication:

- 24 April 2025, pp 260-267

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - The Camaraderie of Influence

- from Part II - Being

-

-

- Book:

- Latinx Literature in Transition, 1848–1992

- Published online:

- 10 April 2025

- Print publication:

- 17 April 2025, pp 126-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A Diplomat-cum-Historian’s Chronicle of US Diplomacy vis-à-vis Africa - US Policy Toward Africa: Eight Decades of Realpolitik Herman J. Cohen. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2020. Pp. 280. $35.00, paperback (ISBN: 9781626378698).

-

- Journal:

- The Journal of African History / Volume 65 / Issue 3 / November 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 March 2025, pp. 464-467

-

- Article

- Export citation

3.10 - Self-Writing

- from History 3 - Forms

-

-

- Book:

- The New Cambridge History of Russian Literature

- Published online:

- 31 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2024, pp 624-642

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

“Embodying” the Intellectual: Edward Said, Public Sphere and the University

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Public Humanities / Volume 1 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 December 2024, e28

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

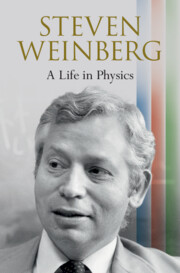

Steven Weinberg: A Life in Physics

-

- Published online:

- 22 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2024

Teaching Pathographies of Mental Illness

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics / Volume 34 / Issue 3 / July 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 October 2024, pp. 321-329

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

8 - Between Public and Private: Letters, Diaries, Essays

- from Part I - Forming the British Essay

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the British Essay

- Published online:

- 31 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 04 July 2024, pp 105-119

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

27 - History Touches Us Everywhere

- from Queer Genre

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of Queer American Literature

- Published online:

- 17 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 470-486

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Artistic Forms of Shaping Ukrainian National Identity by Leon Getz

-

- Journal:

- Nationalities Papers / Volume 53 / Issue 3 / May 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 May 2024, pp. 682-701

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 18 - Re-framing and Re-forming Disability and Literature

- from Part III - Applications: Politics

-

-

- Book:

- Literature and Medicine

- Published online:

- 17 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 313-329

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - African American Soundscapes

- from Part IV - Critical Approaches

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Contemporary African American Literature

- Published online:

- 14 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023, pp 227-238

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

26 - World War Two to #MeToo: The Personal and the Political in the American Feminist Essay

- from Part III - Postwar Essays and Essayism (1945–2000)

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the American Essay

- Published online:

- 28 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 441-459

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 13 - Re-imagining the War

- from Part III - The Memory of War

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to British Theatre of the First World War

- Published online:

- 19 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 October 2023, pp 225-243

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

16 - American Women’s Lives in Graphic Novels

- from Part II - Graphic Novels and the Quest for an American Diversity

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to the American Graphic Novel

- Published online:

- 10 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 272-290

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Life Writing in Comics

- from Part II - Readings

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Comics

- Published online:

- 17 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 31 August 2023, pp 185-203

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

- from Part I - Context

-

- Book:

- Vagabonds, Tramps, and Hobos

- Published online:

- 27 July 2023

- Print publication:

- 10 August 2023, pp 3-23

-

- Chapter

- Export citation