Refine listing

Actions for selected content:

1299955 results in Books

Index

-

- Book:

- Art and Anti-Racism in Latin America

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 305-312

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Family, Vocation, and Humanism in the Italian Renaissance

- Published online:

- 18 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 1-17

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Art and Anti-Racism in Latin America

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 277-304

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Making Babies in Early Modern England

- Published online:

- 12 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 209-245

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Making Babies in Early Modern England

- Published online:

- 12 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 1-16

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

3 - Antinomies and Aporias in Official Human Rights Solidarity Argumentation across the Global South/North Axis

-

-

- Book:

- The Question of Solidarity in Law and Politics

- Published online:

- 22 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 50-70

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

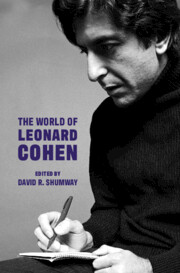

The World of Leonard Cohen

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026

-

- Book

- Export citation

12 - International Law and the Messianic Promise of Solidarity

-

-

- Book:

- The Question of Solidarity in Law and Politics

- Published online:

- 22 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 255-280

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Ottoman Reform at Work

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Regional Trade Agreements, Prosperity and the Global South

- Published online:

- 23 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 255-260

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes on Contributors

-

- Book:

- The Question of Solidarity in Law and Politics

- Published online:

- 22 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp vii-x

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

List of Illustrations

-

- Book:

- George Frideric Handel

- Published online:

- 23 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp vi-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1754–1755

- from The Documents 1750–1755

-

- Book:

- George Frideric Handel

- Published online:

- 23 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 579-680

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Petrarch’s Father, Brother, Son, and the Literary Life

-

- Book:

- Family, Vocation, and Humanism in the Italian Renaissance

- Published online:

- 18 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 18-62

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

maps

-

- Book:

- Peasants to Paupers

- Published online:

- 24 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp xviii-xviii

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

5 - ‘Safe’ Delivery and Recovering from Birth

-

- Book:

- Making Babies in Early Modern England

- Published online:

- 12 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 136-165

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

3 - Who Racializes? Exploring the Demographic Factors of Members of Congress Who Provide Racial Rhetorical Representation through an Intersectional Perspective

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 50-69

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendix C - List of Interviews

-

- Book:

- Triage Bureaucracy

- Published online:

- 24 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 311-315

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

6 - Enclosing Property, Containing Envy

-

- Book:

- Peasants to Paupers

- Published online:

- 24 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 181-204

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

3 - Challenging Whiteness and Europeanness in Argentine Cultural Production

- from Part I - Art and Anti-Racism in the Nation

-

-

- Book:

- Art and Anti-Racism in Latin America

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 97-126

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation