Refine search

Actions for selected content:

25647 results in Literary texts

Textual Note

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare, the Reformation and the Interpreting Self

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 13 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Hamlet, the Fall and Hermeneutical Tragedy

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare, the Reformation and the Interpreting Self

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 13 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp 94-162

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare, the Reformation and the Interpreting Self

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 13 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp 398-420

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare, the Reformation and the Interpreting Self

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 13 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp 372-397

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Epilogue

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare, the Reformation and the Interpreting Self

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 13 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp 360-371

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Seeing Mercy, Staging Mercy in Measure for Measure

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare, the Reformation and the Interpreting Self

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 13 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp 229-293

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare, the Reformation and the Interpreting Self

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 13 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp vi-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare, the Reformation and the Interpreting Self

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 13 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Series Editor’s Preface

-

- Book:

- Shakespeare, the Reformation and the Interpreting Self

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 13 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

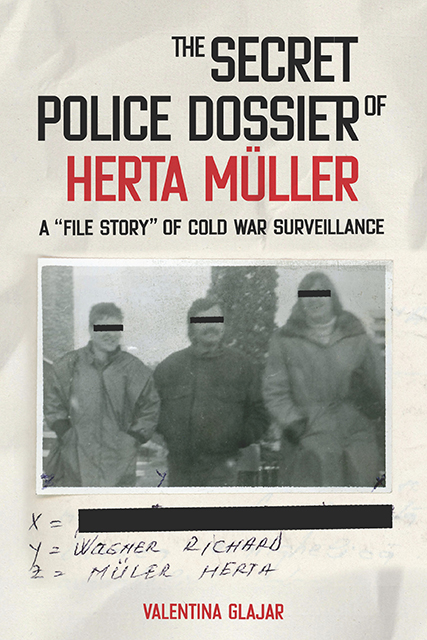

The Secret Police Dossier of Herta Müller

- A 'File Story' of Cold War Surveillance

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 10 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 February 2023

Nostromo

- A Tale of the Seaboard

-

- Published online:

- 08 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 29 June 2023

The Edinburgh Companion to Modernism and Technology

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 07 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 September 2022

Visionary Company

- Hart Crane and Modernist Periodicals

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 07 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 September 2022

The Edinburgh Companion to Vegan Literary Studies

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 07 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 September 2022

British Romanticism and Denmark

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 07 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 31 August 2022

Metaphor in Illness Writing

- Fight and Battle Reused

-

- Published by:

- Edinburgh University Press

- Published online:

- 07 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 September 2022

-

- Book

- Export citation

Part 1 - Literary and Sociohistorical Context

-

- Book:

- Petrarch and the Making of Gender in Renaissance Italy

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 13 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 June 2023, pp 43-44

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Illustrations

-

- Book:

- Petrarch and the Making of Gender in Renaissance Italy

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 13 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 June 2023, pp 9-12

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Afterword

-

- Book:

- Petrarch and the Making of Gender in Renaissance Italy

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 13 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 June 2023, pp 255-260

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part 2 - Making Gender Through Petrarchism

-

- Book:

- Petrarch and the Making of Gender in Renaissance Italy

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 13 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 June 2023, pp 123-124

-

- Chapter

- Export citation