Refine search

Actions for selected content:

25647 results in Literary texts

A Celebration of The Plutzik Poetry Series

- 1962-2022 at the University of Rochester

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

Foreword

-

-

- Book:

- A Celebration of The Plutzik Poetry Series

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024, pp vii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Editors and Contributors

-

- Book:

- A Celebration of The Plutzik Poetry Series

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024, pp 35-36

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Seventh Avenue Express

-

-

- Book:

- A Celebration of The Plutzik Poetry Series

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024, pp 1-30

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- A Celebration of The Plutzik Poetry Series

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024, pp i-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Afterword: Publication History of The Seventh Avenue Express

-

-

- Book:

- A Celebration of The Plutzik Poetry Series

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024, pp 31-34

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Satire, Comedy and Tragedy

- Sterne's 'Handles' to Tristram Shandy

-

- Published by:

- Anthem Press

- Published online:

- 01 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 10 October 2023

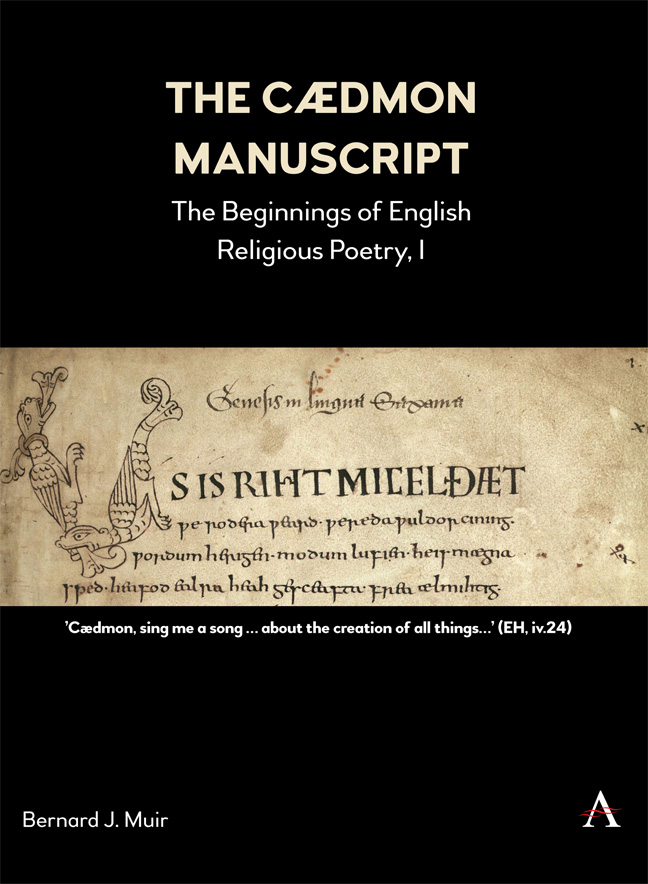

The Cædmon Manuscript

- The Beginnings of English Religious Poetry, I

-

- Published by:

- Anthem Press

- Published online:

- 29 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 September 2023

Quantitative Literary Analysis of the Works of Aphra Behn

- Words of Passion

-

- Published by:

- Anthem Press

- Published online:

- 28 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 09 May 2023

Contents

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - A Writing Life – A Riting Life –A Rioting Life

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp 33-60

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Names: Mother, What is My Name?

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp 61-90

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Coda

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp 173-190

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: Elsewhere

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp 1-32

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Songs: Native Sons Dancing Like Crazy

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp 91-116

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp 191-202

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Miscellaneous Endmatter

-

- Book:

- Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2024, pp 212-212

-

- Chapter

- Export citation