Refine search

Actions for selected content:

16123 results in Animal behaviour

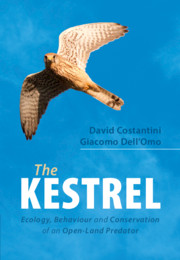

The Kestrel

- Ecology, Behaviour and Conservation of an Open-Land Predator

-

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020

Zooplankton summer composition in the southern Gulf of Mexico with emphasis on salp and hyperiid amphipod assemblages

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom / Volume 100 / Issue 5 / August 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 August 2020, pp. 665-680

-

- Article

- Export citation

8 - Environmental Toxicology

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 134-145

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp ix-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Habitat Use

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 38-47

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Movement Ecology

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 146-157

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The Reproductive Cycle: From Egg Laying to Offspring Care

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 81-107

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Colourations, Sexual Selection and Mating Behaviour

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 57-80

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Systematics and Evolution of Kestrels

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 1-17

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Feeding Ecology

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 18-37

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Ecological Physiology and Immunology

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 108-133

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp v-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Plate Section (PDF Only)

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 215-222

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Conservation Status and Population Dynamics

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 158-175

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 212-214

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 176-211

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Breeding Density and Nest Site Selection

-

- Book:

- The Kestrel

- Published online:

- 29 August 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 August 2020, pp 48-56

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Allometric models for sex ratio determination in all stages of ontogeny of Chelonia mydas from Bahía de los Ángeles, México

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom / Volume 100 / Issue 5 / August 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 26 August 2020, pp. 825-830

-

- Article

- Export citation

Age, growth and reproduction of the golden grey mullet, Chelon auratus (Risso, 1810) in the Golden Horn Estuary, Istanbul

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom / Volume 100 / Issue 6 / September 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 26 August 2020, pp. 989-995

-

- Article

- Export citation