Refine search

Actions for selected content:

1405 results in Computational linguistics

Contents

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp v-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Functional Programming with Haskell

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 33-62

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 397-405

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Foreword

-

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp ix-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp xiii-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Handling Relations and Scoping

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 261-286

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - Communication as Informative Action

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 351-386

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - The Composition of Meaning in Natural Language

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 149-182

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Parsing

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 205-260

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Afterword

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 387-388

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Extension and Intension

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 183-204

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Formal Study of Natural Language

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 1-14

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Lambda Calculus, Types, and Functional Programming

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 15-32

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 389-396

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Continuation Passing Style Semantics

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 287-302

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Formal Semantics for Fragments

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 87-124

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Discourse Representation and Context

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 303-350

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Formal Syntax for Fragments

-

- Book:

- Computational Semantics with Functional Programming

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2010, pp 63-86

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

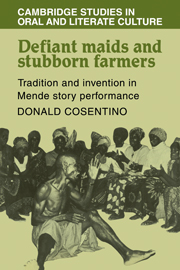

Defiant Maids and Stubborn Farmers

- Tradition and Invention in Mende Story Performance

-

- Published online:

- 04 August 2010

- Print publication:

- 03 June 1982