Refine search

Actions for selected content:

15401 results in Military history

Select Bibliography

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp 193-198

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Christian and Muslim Sources for the Battle of Manzikert: Making Sense of Numbers and Local Topography

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp 63-80

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - The Aftermath of the Battle of Manzikert

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp 165-176

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Illustrations

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp viii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Christian and Muslim Sources for the Battle of Manzikert: Making Sense of the “Battle-Piece"

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp 23-62

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - The Prelude to the Battle of Manzikert

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp 111-132

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp 199-201

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Christian and Muslim Sources for the Battle of Manzikert: Making Sense of the Professional and Cultural Milieu

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp 1-22

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - The Geopolitical and Military Background to the Battle of Manzikert

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp 81-110

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - The Battle of Manzikert

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp 133-164

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp ix-xx

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- The Campaign and Battle of Manzikert, 1071

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 08 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 March 2024, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

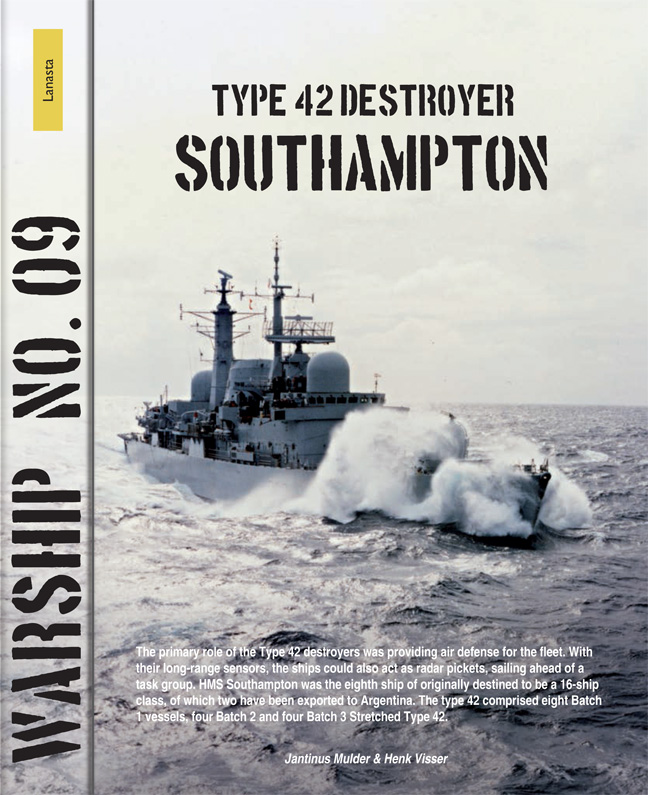

Type 42 Destroyer Southampton

-

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 27 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 29 August 2019

-

- Book

- Export citation

Frigate HMS Leander

-

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 27 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 November 2014

-

- Book

- Export citation

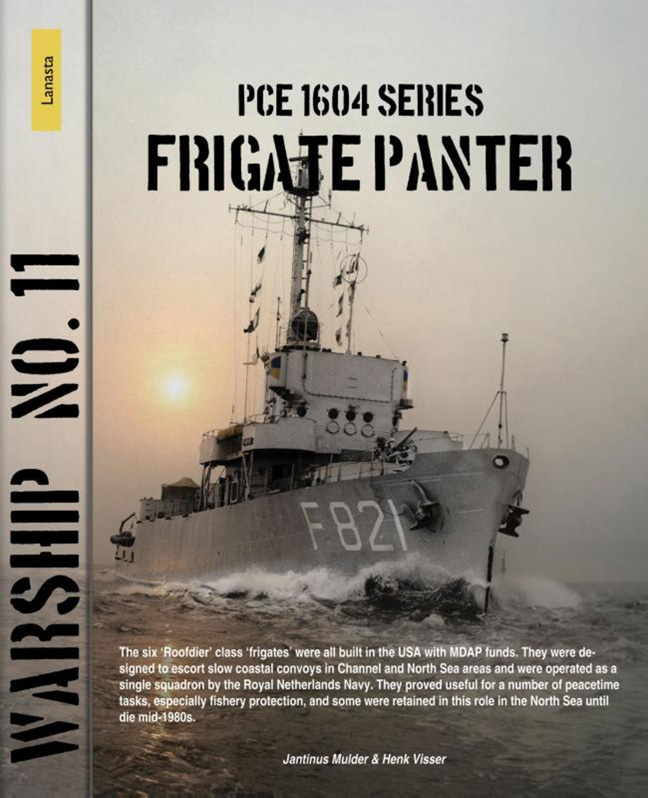

PCE 1604 Series, Frigate Panter

-

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 27 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2021

-

- Book

- Export citation

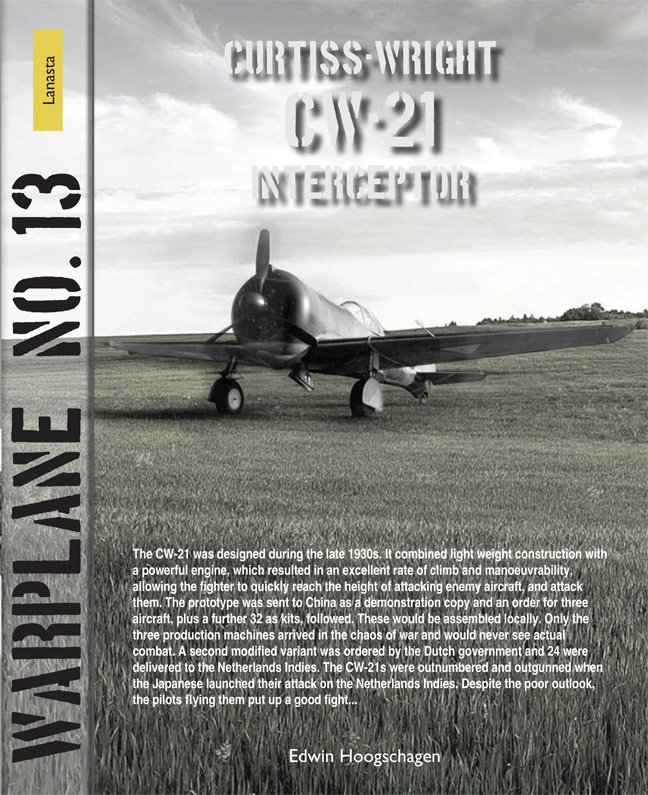

CW-21 Interceptor

-

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 27 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 10 February 2023

-

- Book

- Export citation

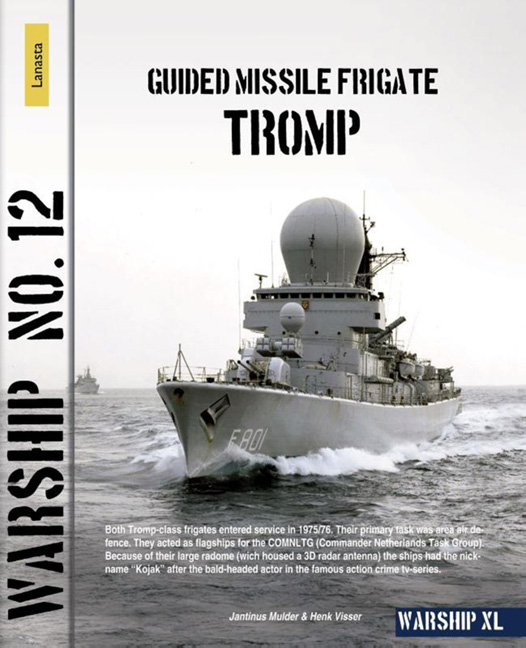

Guided Missile Frigate Tromp

-

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 27 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 October 2021

-

- Book

- Export citation

Fast Combat Support Ship HNLMS Zuiderkruis

-

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 27 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 29 December 2016

-

- Book

- Export citation