Refine search

Actions for selected content:

15418 results in Military history

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- African Americans and the Pacific War, 1941–1945

- Published online:

- 10 September 2018

- Print publication:

- 20 September 2018, pp 261-276

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - A Sexualized South Seas?

-

- Book:

- African Americans and the Pacific War, 1941–1945

- Published online:

- 10 September 2018

- Print publication:

- 20 September 2018, pp 95-135

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- African Americans and the Pacific War, 1941–1945

- Published online:

- 10 September 2018

- Print publication:

- 20 September 2018, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- African Americans and the Pacific War, 1941–1945

- Published online:

- 10 September 2018

- Print publication:

- 20 September 2018, pp xi-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- African Americans and the Pacific War, 1941–1945

- Published online:

- 10 September 2018

- Print publication:

- 20 September 2018, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Behaving Like Men

-

- Book:

- African Americans and the Pacific War, 1941–1945

- Published online:

- 10 September 2018

- Print publication:

- 20 September 2018, pp 176-218

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

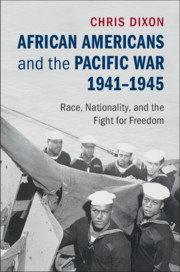

African Americans and the Pacific War, 1941–1945

- Race, Nationality, and the Fight for Freedom

-

- Published online:

- 10 September 2018

- Print publication:

- 20 September 2018

2 - The Structure of Discipline and the Spectre of Indiscipline

-

- Book:

- Morale and Discipline in the Royal Navy during the First World War

- Published online:

- 17 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp 53-91

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- War Stuff

- Published online:

- 16 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Morale and Discipline in the Royal Navy during the First World War

- Published online:

- 17 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - 1865 and After

-

- Book:

- War Stuff

- Published online:

- 16 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp 155-172

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Works Cited

-

- Book:

- War Stuff

- Published online:

- 16 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp 211-246

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - ‘Addressing’ Pay and Conditions

-

- Book:

- Morale and Discipline in the Royal Navy during the First World War

- Published online:

- 17 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp 92-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Ethos on the Eve of War: The Foundations of Paternalism and Democratism

-

- Book:

- Morale and Discipline in the Royal Navy during the First World War

- Published online:

- 17 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp 20-52

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes

-

- Book:

- War Stuff

- Published online:

- 16 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp 173-210

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Morale and Discipline in the Royal Navy during the First World War

- Published online:

- 17 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp 261-266

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Breakdown

-

- Book:

- War Stuff

- Published online:

- 16 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp 131-154

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- War Stuff

- Published online:

- 16 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Sustenance

-

- Book:

- War Stuff

- Published online:

- 16 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp 54-81

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- War Stuff

- Published online:

- 16 August 2018

- Print publication:

- 30 August 2018, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation