Refine search

Actions for selected content:

13409 results in Environmental science

17 - “Intelligent” Water Transfers

- from Part IV - Response

-

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 246-259

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The multiple landscapes of Biedjovággi: Ontological conflicts on indigenous land

-

- Journal:

- Polar Record / Volume 57 / 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 September 2021, e35

-

- Article

- Export citation

12 - The Limarí River Basin

- from Part III - Engineered Rivers

-

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 152-163

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - The Anthropocene and the Earth System

-

- Book:

- Extinctions

- Published online:

- 01 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 11-28

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

16 - River Basin Management and Irrigation

- from Part IV - Response

-

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 235-245

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Declining Environmental Flows

- from Part II - Challenge

-

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 66-76

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - Engineered Rivers

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 77-232

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

14 - The Rio Grande / Río Bravo Basin

- from Part III - Engineered Rivers

-

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 181-219

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part V - Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 271-281

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Extinctions

- Published online:

- 01 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp xi-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 282-294

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Extinctions

- Published online:

- 01 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp xviii-xx

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Reservoirs

- from Part II - Challenge

-

-

- Book:

- Sustainability of Engineered Rivers In Arid Lands

- Published online:

- 16 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 31-45

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendices

-

- Book:

- Extinctions

- Published online:

- 01 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021, pp 211-214

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frozen data? Polar research and fieldwork in a pandemic era

-

- Journal:

- Polar Record / Volume 57 / 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 September 2021, e34

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

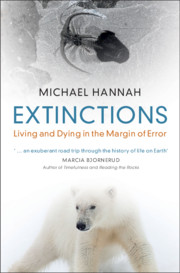

Extinctions

- Living and Dying in the Margin of Error

-

- Published online:

- 01 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 September 2021

Bridgeman Island, Antarctica, ‘burning mount’ or old eroded volcano?

-

- Journal:

- Polar Record / Volume 57 / 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 August 2021, e33

-

- Article

- Export citation

Undecided dreams: France in the Antarctic, 1840–2021

-

- Journal:

- Polar Record / Volume 57 / 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 August 2021, e32

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Mawson’s views on use of natural resources in the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic

-

- Journal:

- Polar Record / Volume 57 / 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 August 2021, e31

-

- Article

- Export citation