Refine search

Actions for selected content:

52494 results in American studies

Appendices

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 207-252

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Crystal Clear

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 92-108

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendix

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 229-252

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Not All Talk Is Cheap

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 131-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - What If It Fails? Is Rhetorical Representation without Legislation Valuable in the Eyes of the Constituents

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 171-186

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 1-27

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Pushing the Agenda or Reacting to the Moment

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 28-49

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 275-280

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 187-206

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

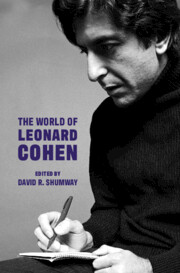

The World of Leonard Cohen

- Coming soon

-

- Expected online publication date:

- January 2026

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026

-

- Book

- Export citation

3 - Who Racializes? Exploring the Demographic Factors of Members of Congress Who Provide Racial Rhetorical Representation through an Intersectional Perspective

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 50-69

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Data and Methods Appendix

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 207-228

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Can Racial Rhetorical Representation Improve Approval Ratings?

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 149-170

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp 253-274

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tables

-

- Book:

- Black Voices in the Halls of Power

- Published online:

- 27 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2026, pp ix-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Emerson, the Philosopher of Oppositions

- Published online:

- 20 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The “Stubborn” Declaration

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to the Declaration of Independence

- Published online:

- 18 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp 76-89

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Reading “Manners”

-

- Book:

- Emerson, the Philosopher of Oppositions

- Published online:

- 20 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp 117-136

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Emerson and Hinduism

-

- Book:

- Emerson, the Philosopher of Oppositions

- Published online:

- 20 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp 179-197

-

- Chapter

- Export citation