Refine search

Actions for selected content:

5162 results in Prehistory

Chapter 2 - Is Determinism Dead?

-

- Book:

- Subsistence and Society in Prehistory

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019, pp 23-49

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendix II - Rock Art Panels and Themes Discussed in This Book

-

- Book:

- Birds in the Bronze Age

- Published online:

- 10 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019, pp 354-378

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Subsistence and Society in Prehistory

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Birds in the Bronze Age

- Published online:

- 10 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019, pp viii-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tables

-

- Book:

- Birds in the Bronze Age

- Published online:

- 10 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019, pp xiii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Incorporating New Methods IV: Phytoliths and Starch Grains in the Tropics and Beyond

-

- Book:

- Subsistence and Society in Prehistory

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019, pp 123-136

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Subsistence and Society in Prehistory

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019, pp 1-22

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Gulf Coast Influence at Moxviquil, Chiapas, Mexico

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Archaeological Journal / Volume 30 / Issue 2 / May 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 October 2019, pp. 183-199

-

- Article

- Export citation

Thinking Gender Differently: New Approaches to Identity Difference in the Central European Neolithic

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Archaeological Journal / Volume 30 / Issue 2 / May 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 October 2019, pp. 201-218

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Trypillia Megasites in Context: Independent Urban Development in Chalcolithic Eastern Europe

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Archaeological Journal / Volume 30 / Issue 1 / February 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 October 2019, pp. 97-121

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Mortuary Pottery and Sacred Landscapes in Complex Hunter-gatherers in the Paraná Basin, South America

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Archaeological Journal / Volume 30 / Issue 1 / February 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 October 2019, pp. 21-43

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

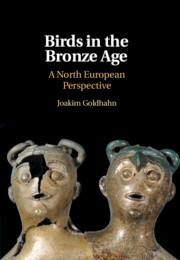

Birds in the Bronze Age

- A North European Perspective

-

- Published online:

- 10 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019

Sometimes Defence is Just an Excuse: Fortification Walls of the Southern Levantine Early Bronze Age

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Archaeological Journal / Volume 30 / Issue 1 / February 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 October 2019, pp. 45-67

-

- Article

- Export citation

Subsistence and Society in Prehistory

- New Directions in Economic Archaeology

-

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019

The Materiality of Shabtis: Figurines over Four Millennia

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Archaeological Journal / Volume 30 / Issue 1 / February 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 September 2019, pp. 123-140

-

- Article

- Export citation

3 - How Far Back Can We Go?

-

- Book:

- Bushmen

- Published online:

- 11 July 2019

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2019, pp 38-55

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Bushmen

- Published online:

- 11 July 2019

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2019, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Naro

-

- Book:

- Bushmen

- Published online:

- 11 July 2019

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2019, pp 101-117

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Bushmen of the Okavango

-

- Book:

- Bushmen

- Published online:

- 11 July 2019

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2019, pp 148-156

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Bushmen

- Published online:

- 11 July 2019

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2019, pp ix-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation