Refine search

Actions for selected content:

708 results in Archaeological Science

10 - Hunting Big Game

- from Part III - Non-symbolic Behaviours

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 128-138

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright Permission for Images

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp xii-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Preliminaries

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 1-28

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Beautifying Bodies

- from Part II - Symbolic Behaviours

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 83-87

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Producing Cave Art

- from Part II - Symbolic Behaviours

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 69-82

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Images

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp ix-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 204-210

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Symbolic Behaviours

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 29-108

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Telltale Neanderthal Teeth

- from Part I - Preliminaries

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 11-28

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Making Stone Tools

- from Part III - Non-symbolic Behaviours

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 111-121

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Teaching Stone-Tool Making

- from Part III - Non-symbolic Behaviours

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 122-127

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Dispersing the Murk

- from Part IV - Implications

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 141-157

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Pursuing an Intriguing but Murky Matter

- from Part I - Preliminaries

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp 3-10

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Neanderthal Language

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020, pp v-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

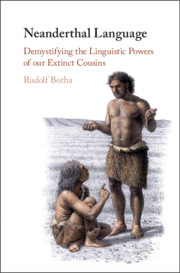

Neanderthal Language

- Demystifying the Linguistic Powers of our Extinct Cousins

-

- Published online:

- 26 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2020

19 - Luminescence Dating

- from Part VI - Absolute Dating Methods

-

-

- Book:

- Archaeological Science

- Published online:

- 19 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 424-438

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Archaeological Science

- Published online:

- 19 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 439-454

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

18 - Radiocarbon Dating

- from Part VI - Absolute Dating Methods

-

-

- Book:

- Archaeological Science

- Published online:

- 19 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 407-423

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part V - Materials Analysis

-

- Book:

- Archaeological Science

- Published online:

- 19 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 333-404

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Dental Histology

- from Part III - Bioarchaeology

-

-

- Book:

- Archaeological Science

- Published online:

- 19 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 170-197

-

- Chapter

- Export citation