8.1 Introduction

The question of transport was central to the original design of European economic integration. However, the inclusion of a specific Transport Title in the Treaty of Rome generated fierce debate on state–market relations. A fundamental source of conflict, which has not fully abated, had to do with the primacy of public services with clear social goals over economic freedoms and competition. Other sources of conflict stem from the existence of different modalities – road, rail, air, and sea. Over the decades, each modality has developed its own technology, management, and operating procedures in a bid to increase its competitiveness and gain market share, usually at the expense of other modalities. Hence, the liberalisation of one modality, be it at national or at EU level, directly impacts the functioning of another (Héritier, Reference Héritier1997). Today, the EU governance of transport can be characterised as ‘recent, gradual, uneven, complex and crisis-driven’ (Kaeding, Reference Kaeding2007: 35).

This chapter examines the extent to which EU governance interventions have been prescribing a commodification of (public) transport services. First, we assess the EU governance of the transport sector prior to the onset of the 2008 financial crisis. In this period, the adoption of a growing number of EU laws, through the ordinary legislative procedure, led to the gradual commodification of transport services, even though the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC) exempted transport services from its free movement of services provisions (Art. 61(1) TEEC, now Art. 58 TFEU) and emphasised the relevance of the ‘concept of a public service’ in the transport sector (Art. 77 TEEC, now Art. 93 TFEU). Despite this, the EU has over time succeeded in commodifying many transport services, particularly in road haulage, aviation, and shipping (Héritier, Reference Héritier1997; Stevens, Reference Stevens2004; Kaeding, Reference Kaeding2007; Kassim and Stevens, Reference Kassim and Stevens2010). In the port, rail, and local public transport sector however, several commodification attempts by the Commission did not fully succeed because of mobilisations by European transport workers and their unions that found allies in the European Parliament and the Council of transport ministers. In a second step, we analyse the prescriptions issued under the new economic governance (NEG) regime (Chapter 2). Analysing the country-specific prescriptions for Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Romania in their semantic, communicative, and policy contexts (Chapters 4 and 5), we are able to show that the commodification of transport services, having stalled in the 2000s, was targeted afresh under the aegis of the NEG regime. Thirdly, we address the extent to which European transport workers’ unions were able to oppose the commodifying governance pressures exerted by ordinary EU laws, the enhanced horizontal market pressures that they in turn triggered, and the EU’s NEG interventions.

8.2 EU Governance of Transport Services before the Shift to NEG

After 1945, most policymakers thought that European reconstruction could not be left entirely to the market and that public utilities should remain in public ownership (Millward, Reference Millward2005). Thus, the drafters of the EEC Treaty gave transport special treatment.

Protecting Transport from the EEC Treaty’s Liberalisation Bent

In the 1950s, the transport sector accounted for a fifth of the combined gross national product of the six original EEC countries and employed 16 per cent of the workers in the industrial sector (Lindberg and Scheingold, Reference Lindberg and Scheingold1970: 142). Because of this and explicit political commitments to social and regional cohesion, the question of transport was bedevilled by fierce debates between governments, their transport ministries, and the European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT), established in 1953, whose ‘opinions counted as authoritative’ (Schot and Schipper, Reference Schot and Schipper2011: 283). A clear division emerged over whether transport should be treated as any other economic sector or whether its peculiarities, such as the public service aspect, should be addressed by emphasising cooperation over competition. Already there were concerns ‘that only a European authority would be able to close unprofitable railway lines because it alone could operate free from national public service considerations’ (Henrich-Franke, Reference Henrich-Franke2008: 67). The ECMT, on the other hand, ‘feared that transport integration would be misused for a political purpose, and that supranational European integration could lead to wasteful or ruinous competition’ (Patel and Schot, Reference Patel and Schot2011: 399).

The extent of these concerns was so grave and progress so slow that its drafters ‘faced the choice to delay the Treaties or to exclude transport’ (Schot and Schipper, Reference Schot and Schipper2011: 274). Neither option was considered acceptable. Thus, a separate Transport Title was included in the EEC Treaty that envisaged a common transport policy; however, there was ‘a great deal of disagreement over how such a policy would be constructed’ (Aspinwall, Reference Aspinwall1995: 480). Provisions were put in place to safeguard isolated inland modes of transport from its overall liberalising bent, and aviation was excluded altogether on national security grounds.Footnote 1

Additional safeguards included the permissibility of state aid insofar as such subventions were for the ‘co-ordination of transport or if they represent reimbursement for the discharge of certain obligations inherent in the concept of a public service’ (emphasis added) (Art. 77 TEEC). Also, unanimity was required where transport was ‘liable to have a serious effect on the standard of living and on employment in certain areas and on the operation of transport facilities’ (Art. 75(3) TEEC). This provision protected the interests of transport users and workers in the sector and remained in force until the Lisbon Treaty. According to most member states, the separate Transport Title in the EEC Treaty protected the transport sector from the application of other Treaty articles governing such matters ‘as competition, state aids and the freedom to provide services’ (Stevens, Reference Stevens2004: 44). Despite the Commission’s enthusiasm for creating a common transport market (Commission, Memorandum, COM (61) 50 final; Tindemans, Reference Tindemans1976), the Council staunchly defended decommodified transport services. In the 1970s, the Council exempted, for instance, the question of transport from the first wave of procurement directives. Whereas EEC policymakers reached ‘almost magical compromises’ in the agricultural sector, which was also governed by a specific Treaty Title, there was an ‘almost total deadlock’ in the transport sector (Lindberg and Scheingold, Reference Lindberg and Scheingold1970: 163).

Towards the Commodification of Transport Services by EU Law

Following the first EU enlargement in 1973, liberalising transport became again a political issue. UK governments, along with Dutch ones, spearheaded the deregulatory drive but, with unanimity voting prevailing in the Council, their efforts were initially readily prevaricated. The application of neoliberal paradigms to transport, however, was also assisted by developments that originated outside Europe, namely, the deregulation of US aviation in the late 1970s (Kassim and Stevens, Reference Kassim and Stevens2010). Following this, the Commission, in the first half of the 1980s, published three reports on inland (1983), maritime (1984), and air (1985) transport with the objective of launching ‘an irreversible liberalisation process’ that ‘was intended to work like a snowball getting both larger and faster as it rolled down hill’ (Stevens, Reference Stevens2004: 57).

For the reasons cited, civil aviation and maritime transport were excluded from the EEC Treaty (and therefore fatefully also from the protections of its Transport Title) and were instead regulated by intergovernmental agreements. In an important European Court of Justice (ECJ) case, known as Nouvelles Frontières,Footnote 2 inter-airline agreements were found to be illegal ‘in the absence of any Community regulation exempting them from the normal application of Treaty competition rules’ (Stevens, Reference Stevens2004: 58). This case was a ‘turning point for EU aviation’ (Kaeding, Reference Kaeding2007: 47), which received a further boost when the European Parliament, along with the Dutch government, brought the Council before the ECJ, which ruled that the Council had infringed the Treaty by failing to ensure freedom to provide services in the sphere of international transport.Footnote 3 Constituting a ‘watershed for supranational transport policy’ (Kerwer and Teutsch, Reference Kerwer, Teutsch and Windhoff-Héritier2001: 29), this ruling meant that the Council could no longer insist on harmonisation as a precondition to liberalisation (Erdmenger, Reference Erdmenger1983; Héritier, Reference Héritier1997). This emboldened the pro-commodification advocates reorganising themselves at European level (Jensen and Richardson, Reference Jensen and Richardson2004).

In 1985, the Commission (White Paper, COM (85) 310: 27) once again emphasised that transport was ‘of prime importance’ for the internal market and framed it as a normal economic activity without mentioning its role as a public service. That said, the rail sector was spared and considered as being ‘not of direct relevance to the internal market’ (White Paper, COM (85) 310: 30). Under the Single European Act, qualified majority voting was extended to many areas including aviation and maritime. This change ‘made it harder to resist the neoliberal agenda embedded in the Treaties’ (Stevens, Reference Stevens2004: 246), but not impossible. The successful adoption of three liberalisation packages between 1987 and 1992 created the single European aviation market. Buoyed by this, the EU turned its liberalisation sights on road haulage, rail, and other network industries (Chapter 7). The liberalisation of road haulage was contentious on the question of cabotage (the operation of non-resident hauliers in foreign markets); however, on account of the ‘weakened position of the anti-liberalization actors’ (Héritier, Reference Héritier1997: 541), agreement on a liberalisation package between member states was possible, formally at least (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2002). Several member states, including Italy and Germany, regulated road haulage to protect their railways from intermodal competition. The latter proposed a road toll for trucks from other member states to protect its railways and contribute to road-building costs. This, at the behest of the Commission, was deemed illegal by the ECJ. Hence, railways were to be susceptible to competition from road haulage, thereby contributing to its liberalisation.

Regarding the question of rail liberalisation, Directive 91/440/EEC ‘is the most important Community measure to improve the competitiveness of rail transport’ and required the organisational separation of railway operations and infrastructure management (Commission, Communication (1998) 202/final). This separation is also important in the context of monetary union, a point we return to below. In the 1990s, EU rail legislation (e.g., the Directives 95/18/EC on licensing of railway undertakings or 95/19/EC on railway infrastructure capacity) constituted a false start, as it focused on ‘less demanding’ reforms (Knill and Lehmkuhl, Reference Knill and Lehmkuhl2002: 272) and was characterised by a high degree of ambiguity, which mirrored the resistance by governments, such as the French (Kerwer and Teutsch, Reference Kerwer, Teutsch and Windhoff-Héritier2001: 46), and by the state-owned railway companies, represented by the Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies (CER). To overcome that resistance, the Commission (White Paper, COM (96) 421) first favoured a ‘big bang’ liberalisation; but, once the Commission realised that support from the Council was not forthcoming, it adopted a more gradual approach (Dyrhauge, Reference Dyrhauge2013: 56). Hence, rail liberalisation really began in earnest only in the 2000s. By then however, the Amsterdam Treaty had enhanced the status of the European Parliament in EU transport policymaking. Subsequently, the Parliament became a co-legislator with the Council; this also meant becoming a target for both pro- and anti-commodification groups (see section 8.4).

Under their Lisbon growth agenda for the 2000s, EU leaders envisaged greater service liberalisation as well as the curbing of state aid (European Council, 2000: 20). The conservative Spanish EU Transport Commissioner Loyola de Palacio spearheaded this endeavour and sought to liberalise the rail sector, public transport, and port services, with mixed results. All three legislative attempts triggered countermovements by unions and other public sector advocates. Regarding railways, three packages of EU railway laws were agreed, between 2001 and 2007, with the emphasis placed first on rail freight given its role in the movement of goods and its lesser political standing in terms of public salience. The first package envisaged competition on Trans European Rail Freight Network routes from 2003 and for all international rail freight from 2008. The second package, adopted in 2004, accelerated the liberalisation of rail freight services by fully opening the rail freight market to competition as of January 2007. The third package, adopted in 2007, aimed to open international passenger transport to market mechanisms by 2010. We return to the rail acquis below, but first let us consider one of the most overlooked pieces of EU legislation for public transport (Finger and Messulam, Reference Finger, Messulam, Finger and Messulam2015: 4).

Public services obligations (PSOs) have been central to the state’s provision of public transport services and ‘can best be described as an activity carried out in the public interest, either directly by the authorities or by private undertakings under the control or supervision of the public authorities’ (Degli Abbati, Reference Degli Abbati1987: 21). Questions pertaining to state aid and competition come under the remit of the Commission’s DG Competition, which by the 2000s was no longer ‘a sleepy, ineffectual backwater of Community administration’ (Wilks and McGowan, Reference Wilks, McGowan, Wilks and Doern1996: 225).Footnote 4 Building on both the 2001 transport White Paper (COM (2001) 370) and the 2004 White Paper on services of general economic interest (COM (2004) 374), the Commission proposed a new Regulation that sought to streamline rules governing state aid by introducing compulsory competitive tendering in public transport. A protracted process ensued, involving three attempts by the Commission to have the regulation adopted. Following a landmark caseFootnote 5 on state aid in the public transport sector, the ECJ ruled that ‘where subsidies are regarded as compensation for the services provided by the recipient undertakings in order to discharge public service obligations, they do not constitute state aids’ (emphasis added) (Bovis, Reference Bovis2005: 572). This Altmark ruling, along with amendments introduced by the European Parliament and the Council, meant that PSO Regulation 1370/2007 allowed for the possibility both of direct award and of competitive tendering, that is, member-state discretion in the awarding of public contracts prevails. This was welcomed by pro-public services advocates, such as the European Transport Workers’ Federation (ETF) and several member states, as the adopted regulation differed from the Commission’s original market-oriented proposal (ETF, 2010).

Rail liberalisation followed the same logic as other network industry liberalisations, such as telecommunications and electricity (Chapter 7). This logic centres on privatisation, regulatory independence, unbundling, and competition (Florio, Reference Florio2013). EU legislators are limited by Art. 345 TFEU regarding privatisation (Akkermans and Ramaekers, Reference Akkermans and Ramaekers2010), but the dividing of services from infrastructure, that is, unbundling and fostering competition, overseen by an independent regulator, remain paramount to EU liberalisation, which can indirectly, but not unintentionally (Clifton, Comín, and Diaz Fuentes, Reference Clifton, Comín and Diaz2003), put pressure on governments to pursue (partial) privatisation. This gradual approach seeks to foster competition by establishing a regulatory framework that ensures that national governments stay at arm’s length. Here, the Commission, in relation to unbundling, has a clear and long-standing preference for vertical separation ‘as a more effective means to alleviate the infrastructure monopoly problem, ensure neutrality and allow new entrants on the market of train operations’ (van de Velde, Reference van de Velde, Finger and Messulam2015: 53). However, alternative governance structures also exist (Dyrhauge, Reference Dyrhauge2013: 42–50).

The three rail liberalisation packages sought to restrict state interference by promoting vertical separation, which concretely involves (1) splitting up the state-owned railway company into separate passenger and freight units; (2) establishing an infrastructure manager to oversee non-discriminatory charging and the granting of access to the rail network, based on an economic rationale rather than social needs; and (3) creating an independent rail regulator ‘to whom applicants can appeal if they consider that the rules have not been applied fairly’ (Stevens, Reference Stevens2004: 99). The Commission depends on disgruntled private enterprises taking anti-competition cases (Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2011) to ensure liberalisation. However, cases taken by private rail companies challenging state-owned rail companies’ (alleged) abuse of position have not materialised.

Following the Swedish and British national liberalisation processes, the Commission pushed for vertical separation. Each of its three legislative liberalisation packages ended in conciliation between the European Parliament and Council (Dyrhauge, Reference Dyrhauge2013: 88). In the legislative process, vertical separation was resisted by key member states, notably Germany and Italy, ensuring a degree of heterogeneity. In 2010, the Commission nonetheless filed actions against thirteen member states, including GermanyFootnote 6 and Italy,Footnote 7 for having allegedly breached the first railway package. Most member states undertook only a minimum separation, thereby allowing the preservation of national rail holding groups, such as Deutsche Bahn. The Commission argued that the rail acquis means that the infrastructure manager, such as Deutsche Bahn Netz, cannot form part of a holding company that also comprises the railway undertakings. In other words, holding companies, such as Deutsche Bahn, were problematic. In addition, the Commission was critical of the fact that the German and the Italian infrastructure operator’s independence was not supervised by an independent agency. Following the opinion of Advocate General Niilo Jääskinen, the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) rejected the Commission’s complaint regarding Germany and Italy. Moreover, the Court noted that the rail acquis requires only legal and accounting separation, which are present in the holding company model (Rail Gazette, 7 September 2012). Despite evidence to the contrary (van de Velde, Reference van de Velde, Finger and Messulam2015), the neoliberal Estonian EU Transport Commissioner Siim Kallas said after the ruling that the Commission ‘remains convinced that a more effective separation between an infrastructure manager and other rail operations is essential to ensure non-discriminatory access for all operators to the rail tracks’ (emphasis added) (Politico.eu, 28 February 2013).

Another key development in EU transport governance is the Lisbon Treaty (Schweitzer, Reference Schweitzer and Cremona2011: 52), which abolished the unanimity requirement in the Council for transport sector-specific laws that ‘might seriously affect the standard of living and level of employment in certain regions’ (Art. 75(3) TEEC). When adopting EU laws in the field, EU legislators are henceforth tasked only to consider the following: ‘account shall be taken of cases where their application might seriously affect the standard of living and level of employment in certain regions, and the operation of transport facilities’ (emphasis added) (Art. 91(2) TFEU). In other words, a significant institutional safeguard that protected the initial social purpose of European transport service governance was finally removed. Whereas the Commission’s (MEMO/09/531) corresponding explanatory memo simply failed to mention it, trade unionists overlooked this change in the Lisbon Treaty debates (Béthoux, Erne, and Golden, Reference Béthoux, Erne and Golden2018). This modification was still very much welcomed by pro-commodification advocates, as it facilitated the adoption of new EU laws in the field, which we assess at the end of the post-financial crisis developments section below. Before turning to the EU’s response to the 2008 crisis and its implications for public transport services, we must assess a precursor to the NEG regime that is bound up in economic and monetary union (EMU). We briefly consider this next.

EMU and the Commodification of Public Transport Services

The EMU accession criteria involved a forensic surveillance process resulting in a strong conditioning effect on state–market relations, especially on public transport infrastructure (Savage, Reference Savage2005). To join the eurozone, national governments had, among other things, to have a public deficit of less than 3 per cent of GDP. Albeit indirect, pressures arising from the EMU criteria were particularly relevant for the rail sector, which ‘had become a growing burden on the public finances’ (Finger and Messulam, Reference Finger, Messulam, Finger and Messulam2015: 1). In addition to liberalisation, EU rail legislation accordingly sought ‘to reduce railway debt to a level that does not impede sound financial management’ (Commission, COM (1998) 202 final: 2). Here, member states devised novel ways to manage public debt, which included reforming the transport sector. For some member states, reforms constituted a significant reversal of the entire post-World War II policy paradigm (Clifton, Comín, and Diaz Fuentes, Reference Clifton, Comín and Diaz2003). Italy, for example, topped the OECD privatisation ranking between 1995 and 1999 (Savage, Reference Savage2005: 129). These initiatives, all in the name of meeting the EMU criteria, were complemented by a hiring freeze, hospital closures (see Chapter 10), and reduced rail subsidies.

In this context, the Commission promoted three interrelated measures of immediate relevance for public transport services and their gradual commodification. The first has already been mentioned above in terms of establishing an environment for competition, namely, the separation of infrastructure managers from incumbent rail companies so as ‘to prevent state subsidies for public service obligations being used to finance commercial activities’ (Dyrhauge, Reference Dyrhauge2013: 85–86). Secondly, there was the creation of independent regulatory agencies, and once again there was a fiscal aspect. For instance, in the rail sector, regulatory agencies were envisaged as operating not only to ‘prevent conflict of interests’ and enhance competition but equally importantly ‘to reduce its reliance on public financing’ (Dyrhauge, Reference Dyrhauge2013: 54). Thirdly, there was the question of EU cohesion funds, which went towards the construction of infrastructural projects. Although often portrayed as a side-payment to the EU’s periphery in exchange for EMU (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2001), the cohesion funds were ‘anything but a value-free pursuit’ (Nanetti, Reference Nanetti and Hooghe1996: 60). Rather, they were a vehicle for ‘stimulating the mobilisation of domestic private capital and attracting private capital from outside the country’ (1996: 66). This was achieved by public–private partnership (PPP), which can ‘dramatically improve the deficit position of member states’ (Savage, Reference Savage2005: 149).

The question of excessive deficits never really went away; however, EU executives lacked the teeth to deal with member states in troubled fiscal waters in the first half of the 2000s (Heipertz and Verdun, Reference Heipertz and Verdun2010). Following the 2008 crisis, EU leaders remedied this weakness through the adoption of the NEG regime (Chapter 2). From the above, it is clear that the liberalisation of rail and local public transport has faced numerous obstacles, including diverging member-state preferences and counter-mobilisations (see section 8.4). On rail liberalisation, Helene Dyrhauge (Reference Dyrhauge2013: 160) writes that ‘EU railway market opening is not a highspeed train which is quickly reaching its destination … instead it is a slow regional train stopping at all stations’. Such ‘stations’ include a general transposition deficit (Kaeding, Reference Kaeding2007), a lack of infringement proceedings by private litigants against incumbents, failed infringement proceedings by the Commission, and consequently persistent regulatory heterogeneity regarding both the degree of independence of the regulator and the degree of vertical separation. Might the NEG regime provide the Commission and national finance ministries with a new avenue whereby awkward national transport ministries, the European Parliament, a not always reliable CJEU, and recalcitrant transport unions can be circumvented?

8.3 Governing the Transport Sector through Commodifying NEG Prescriptions

In this section, we assess the extent to which the EU’s NEG regime allowed the Commission to circumvent the strong anti-commodification contingent that it inevitably faces in the more democratic governance mechanisms of the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure. Here, we analyse the policy orientation of NEG prescriptions relevant for transport. Hundreds of country-specific recommendations (CSRs) have been issued by the EU but, rather than attempting to analyse all NEG prescriptions contained in CSRs for all countries from 2009 to 2019 without regard to their context-specific meaning (see Chapters 4 and 5), our focus is on Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Romania, which we know very well and are in different positions in the EU’s integrated but also uneven political economy. The objective is to determine whether the prescriptions further a commodification agenda across countries, whilst taking into consideration prescriptions’ coercive power, which relates to the position of a country within NEG’s enforcement regime at a given time (Chapter 5). Doing so enables us to go beyond broad-brush, macro-theories of neoliberalism and commodification (Bruff, Reference Bruff2014; Baccaro and Howell, Reference Baccaro and Howell2017; Hermann, Reference Hermann2021) and offers a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms underpinning the Commission’s transport-related policies across space and time.

Following the analytical framework outlined in Chapters 4 and 5, we first identified the NEG prescriptions on the provision of public transport services and people’s access to them, identifying common themes (i.e., common formulations of semantically similar prescriptions). In contrast to the water (Chapter 9) and the healthcare (Chapter 10) sectors, EU executives issued no prescriptions relating to people’s access to transport services. We therefore assessed the transport-related NEG prescriptions in terms only of the remaining three categories of our analytical framework, pertaining to (a) resource levels and the (b) sector- and (c) provider-level governance mechanisms for the provision of public transport services. Whereas the resources category has a quantitative dimension, the sector- and provider-level mechanisms categories have a qualitative dimension. Together, these dimensions can shed light on whether we can speak of a transnational commodification script informing the EU’s NEG prescriptions in transport and, if so, along what dimensions it has been applied.

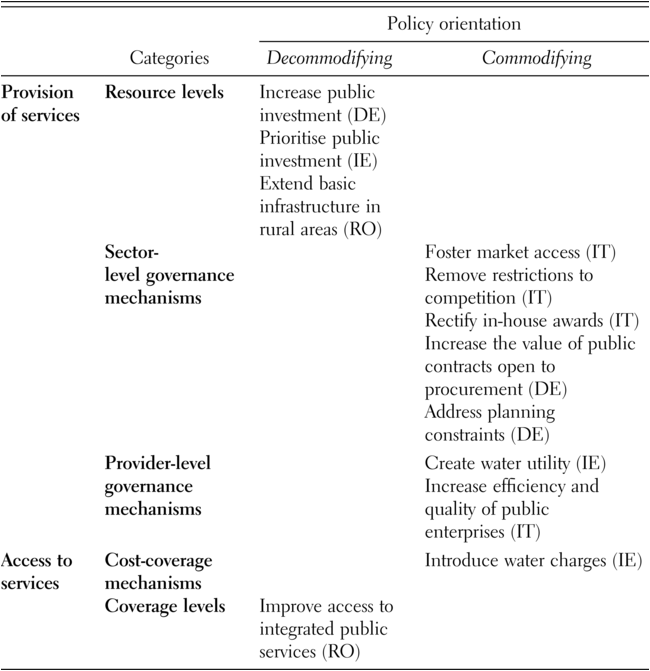

Table 8.1 presents the themes of all transport-related NEG prescriptions for Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Romania from 2009 to 2019. We assess not only the prescriptions that mention transport services explicitly but also those for network industries and local public transport services where there is a semantic link to transport, typically in CSRs’ recitals.

Table 8.1 Themes of NEG prescriptions on transport services (2009–2019)

| Categories | Policy Orientation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Decommodifying | Commodifying | ||

| Provision of public services | Resource levels | Increase public investment (RO/DE) Improve infrastructure capacity (IT) Prioritise public investment (IE) Focus investment in infrastructure quality (IT) | Close railway lines (RO) |

| Sector-level mechanisms | Restructure Transport Ministry and regulatory agency (RO) Strengthen regulator’s independence (RO/DE) Lease railway lines (RO) Increase efficiency of rail passenger services (RO) Increase efficiency in railway planning (RO) Reform rail sector to make it more attractive for cargo (RO) Promote competition in the transport sector (RO/IT/DE) Implement performance management scheme (RO) Promote competition in the local transport sector (RO/IT/DE) Set-up regulatory authority (IT) Operationalise regulatory authority (IT) | ||

Provider-level mechanisms | Privatise state-owned company (RO) Reduce payment arrears of state-owned rail company (RO) Restructure state-owned enterprises (RO/IT) Restructure local public services (IT) | ||

Access to public services | Cost-coverage mechanisms | ||

| Coverage levels | |||

Country code: DE = Germany; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; RO = Romania.

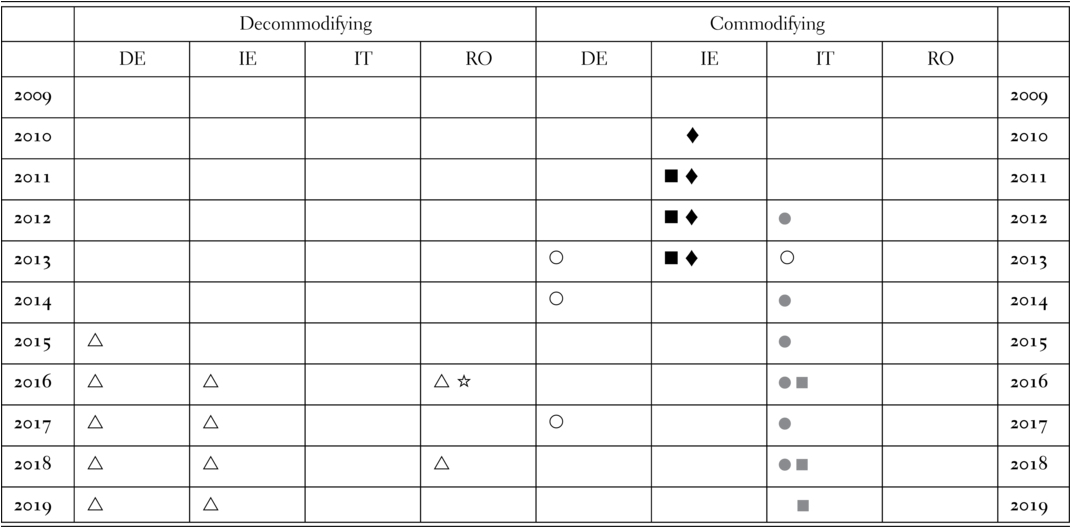

Table 8.2 represents all transport-related NEG prescriptions across our four countries and time, based on the categories to which they belong, their policy direction, and their coercive power.

Table 8.2 Categories of NEG prescriptions on transport services by coercive power

| Decommodifying | Commodifying | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | ||

| 2009 | ⦁4 | 2009 | |||||||

| 2010 | ⦁2 ■ | 2010 | |||||||

| 2011 | ⚪2 | ▲ ⦁18 ■2 | 2011 | ||||||

| 2012 | ⚪ | ▲ ⦁12 ■2 | 2012 | ||||||

| 2013 | △ | ⚪ | ⚪3 | ⦁6 ■6 | 2013 | ||||

| 2014 | ⚪ | ⚪ □ | 2014 | ||||||

| 2015 | ⚪ | □ | 2015 | ||||||

| 2016 | △ | △ | △ | ⚪ □ | 2016 | ||||

| 2017 | △ | 2017 | |||||||

| 2018 | △ | △ | 2018 | ||||||

| 2019 | △ | △ | △ | □ | 2019 | ||||

Thematic area: △ = resources; ⚪ = sector-level governance; □ = provider-level governance.

Country code: DE = Germany; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; RO = Romania.

Coercive power:⦁▲■ = very significant; ![]()

![]()

![]() = significant; ⚪△□ = weak.

= significant; ⚪△□ = weak.

Superscript number equals number of relevant prescriptions.

A simple glance at Tables 8.1 and 8.2 reveals that all qualitative NEG prescriptions on sector- or provider-level governance mechanisms point in a commodifying policy direction. It is equally noteworthy that Germany, Italy, and Romania received commodifying prescriptions. Regardless of the countries’ unequal locations in the EU’s political economy, the Commission and the Council of finance ministers clearly tasked all governments to foster the marketisation of the public transport sector but, whereas the constraining power of the NEG prescriptions for Germany was weak, those for Romania and Italy were much more constraining, as indicated by the respective black and grey colours of the symbols in Table 8.2 (see Chapter 2).

Contrariwise, most quantitative, resource-level-related prescriptions point in a decommodifying direction. By contrast to the commodifying prescriptions mentioned above, the coercive power of the decommodifying ones has always been weak, with two exceptions. We must reiterate that transport services were also affected by the intersectoral prescriptions on employment relations and public services in general, discussed in Chapters 6 and 7. This is significant, as most NEG prescriptions on the curtailment of spending on public services were intersectoral. This was also relevant in the Irish case.

Table 8.2 indicates that EU executives issued only decommodifying NEG prescriptions for Ireland. This, however, does not indicate a lack of commodifying policy interventions in Irish transport services. Sure, Ireland’s island location reduced the relevance of its domestic transport networks for the European single market. Because of this, Ireland had already received a derogation from the liberalising EU rail acquis before the financial crisis. More important for the single market, however, were Ireland’s ferry and air links to the United Kingdom and the continent. As successive Irish governments had already commodified aviation and ferry services (Sweeney, Reference Sweeney2004: 35; Mercille and Murphy, Reference Mercille and Murphy2016: 697), there was no need for corresponding NEG prescriptions. Irish governments had also increased the role of private operators in local public transport services, ‘not by head-on confrontation with the unions, but by ensuring that the existing state companies only play a limited role in new services’ (Wickham and Latniak, Reference Wickham and Latniak2010: 163). In 2004, for example, the government increased the competitive pressures on Dublin Bus by conceding the operation of Dublin’s new light rail service to the French transnational corporation Veolia. For the same reason, Irish governments also supported Aer Lingus’ low-cost competitor, Ryanair, at crucial moments of its history (Allen, Reference Allen2007: 226–227; Golden and Erne, Reference Golden and Erne2022).

After the financial crisis, the commodification of Irish public transport services gained even more traction, even before the arrival of the Troika in Ireland in December 2010. In 2009, Irish legislators had already transferred the task of public transport governance from both the national transport ministry and the Dublin Transportation Office to an independent National Transport Authority (NTA). In July 2010, the Irish finance minister tasked a Review Group on State Assets and Liabilities (2011: 1) to propose a list of measures ‘to de-leverage the state balance sheet through asset realisations’. In 2011, the Group recommended ‘that the Aer Lingus shares’ (2011: 87) and stated-owned ‘bus businesses competing directly with private operators should be disposed of’ (2011: 99). Furthermore, the government should seek ‘to limit the level of public subsidy’ for public transport providers and the amount of ‘capital to be invested in further transport projects’ and envisage ‘the privatisation of all or part of Dublin Bus’ (2011). In turn, the NTA conceded 10 per cent of Dublin’s bus routes to private operators (Mercille and Murphy, Reference Mercille and Murphy2016: 697), but Irish governments curtailed public transport expenditure so radically that even EU executives felt obliged to issue countervailing NEG prescriptions after 2016, as we shall see below.

Hence, the absence of commodifying NEG prescriptions for Ireland does not indicate EU support for decommodified public transport services but rather overzealous spending cuts and marketising reforms by Irish governments that made such NEG prescriptions needless. This once more shows that the meaning of NEG prescriptions can only be understood in their specific semantic, communicative, and policy context. To make better sense of the NEG regime’s quantitative and qualitative dimensions in the transport sector across all our four countries, we now assess the orientation of all transport-related NEG prescriptions in more detail category-by-category.

Prescriptions on the Provision of Services

Resource levels: This section speaks to NEG’s quantitative dimension and to the question of commodification and decommodification. From Table 8.2 we can see that on the right, commodification side of it there is a singular, but repeated, resource-level-related commodifying prescription, which tasked the Romanian government to ‘identify and close … lowest cost recovery segments of the railway lines’ (P-MoU, Romania, 29 June 2011: 12). Subsequently, around 1,200 km of line were closed or leased out (European Commission, 2013: 51). The upshot of this was to restrict users’ access to (rural) transport services either because of cessation of the service or via an increase in prices, which were implemented (European Commission, 2014a: 17). In essence, their closure put important public services and goods beyond even commodification, all in the name of cost reduction. In 2015, the Commission nevertheless lamented that some ‘unsustainable railway lines are still not closed’ (Commission, Country Report Romania SWD (2015) 42: 27). Hence, Romania’s line closures represent ‘a real cautionary showcase’ (Global Railway Review, 24 September 2015) that unwittingly contradicted the enhanced role for rail laid out in the EU’s 2011 White Paper on transport.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the Irish Government also cut its capital expenditure on public transport, from €900m in 2008 to a low point of €254m in 2012, and its current expenditures from €343m in 2008 to a low point of €236m in 2015 (Hynes and Malone, Reference Hynes and Malone2020). These cuts, however, were triggered not by explicit, transport-related NEG prescriptions but by the intersectoral NEG prescriptions on public expenditure cuts and the Irish government’s turn to austerity that predated the arrival of the Troika (see Chapter 7). The Italian and German governments equally curtailed their public spending on transport to such an extent that EU executives in turn felt obliged to later issue countervailing prescriptions.

Looking at the left side of Table 8.2, we see that all countries under study also received prescriptions on resource levels that pointed in a decommodifying direction. Between 2012 and 2019, EU executives repeatedly tasked governments to increase or prioritise public investment in transport. For instance, the German government received an NEG prescription to ‘achieve a sustained upward trend in public investment, especially in infrastructure’ (Council Recommendation Germany 2016/C299/05) on account of Germany’s ‘sound fiscal position overall’ (Commission, SWD (2014) 406 final: 3). Despite federal spending on transport infrastructure having increased from an average of around €10bn annually over the period 2010–2014 to €12.3bn in 2016, EU executives stated that this ‘still falls short to meet the additional annual public investment requirement’ (Commission, Country Report Germany SWD (2016) 75: 46). Here, it needs to be borne in mind that Germany’s enduring underinvestment in transport preceded the debt break, enacted in its federal constitution in 2009, and German finance ministers’ proclaimed goal of a Schwarze Null: ‘black zero’. Consequently, ‘spending on public infrastructure has been on a downward trend for a long time’ (emphasis added) (Commission, SWD (2014) 406 final: 7), with ‘transport infrastructure’ being ‘affected in particular’ (2014: 9). The upward investment is seen as necessary to ‘maintain and modernise Germany’s public infrastructure’ (2014: 9), which is ‘crumbling’ (Economist, 17 June 2017).

Ireland too received transport-related decommodifying prescriptions on an annual basis between 2016 and 2019, but the gist of these prescriptions differed from those issued to Germany. The NEG prescriptions issued to the Irish government were: ‘Enhance the quality of expenditure … by prioritising … public infrastructure, in particular transport’ (emphasis added) (Council Recommendation Ireland 2016/C 299/16) and better ‘target government expenditure, by prioritising public investment in transport’ (emphasis added) (Council Recommendation Ireland 2016/C 299/16; Council Recommendation Germany 2017/C 261/07). As these decommodifying prescriptions tasked the government to divert public money away from other public sectors towards maintaining and upgrading public transport infrastructure however, they were still speaking to the austerity doctrine of doing more with less (Hermann, Reference Hermann2021). After the continued deterioration in the financial positions of Ireland’s transport providers triggered waves of strike action in 2016 and 2017 at Luas, Bus Éireann, and Iarnród Éireann, respectively (Palcic and Reeves, Reference Palcic and Reeves2018; Maccarrone, Erne, and Regan, Reference Maccarrone, Erne, Regan, Müller, Vandaele and Waddington2019), the government at last increased its spending on public transport once again. Since then, capital investment rose to €496m and current spending to €302m in 2019 (Hynes and Malone, Reference Hynes and Malone2020).

In 2019, all four countries received a transport-oriented decommodifying prescription. These came in the wake of the Italian Morandi Bridge disaster in August 2018, which killed 43 people and left 600 people homeless. A symbol of Italy’s miracolo economico, the Morandi bridge had been privatised in the late 1990s along with 4,000 miles of toll roads in the context of satisfying the Maastricht public deficit criteria (New York Times, 5 March 2019). The prescription urged the Italian government to focus on ‘the quality of infrastructure’ (Council Recommendation Italy 2019/C 301/12). Consequently, EU executives granted Italy an allowance of €1bn to secure its infrastructure, as the ‘state of repair is a clear source of concern’ (Commission, Country Report Italy SDW (2019) 1011: 52). The ailing state of transport infrastructure also informed the corresponding prescriptions for the other three countries. Furthermore, the 2019 prescriptions on public investments in transport infrastructure were linked semantically to another emerging policy script, namely, the looming climate emergency and the transition to a greener economy (von der Leyen, Reference von der Leyen2019). As seen above however, these concerns had hardly been a priority in the preceding years.

Sector-level governance mechanisms: Prescriptions under this category are the most prevalent, recurring in tranches across Germany, Italy, and Romania. This prevalence arises because EU public sector liberalisation occurred primarily at sectoral level (Héritier, Reference Héritier1997; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2002; Smith, Reference Smith2005: Leiren, Reference Leiren2015). At the same time, liberalisation attempts were limited, as EU legislators were able to prescribe only new regulatory frameworks that sought to foster competitive dynamics by gradually removing the exclusive rights of public operators (Florio, Reference Florio2013). Thus far however, the power of the supranational, regulatory governance agencies that have emerged in the transport sector is very limited.Footnote 8 Hence, the governance of the sector, namely, in rail and local public transport, still resides predominately with member states. This has produced mixed results with regard to the independence of transport governance from partisan, democratic governments – hence, the focus of NEG prescriptions on public transport governance across three of the four countries under study.

Romania received numerous prescriptions on the sectoral governance of rail. For instance, EU executives tasked the Romanian government to ‘pursue the restructuring of the Ministry of Transport’ (MoU, Romania, 23 June 2009: 5), with similar prescriptions returning in follow-up (supplementary) agreements (MoU, Romania, 1st addendum, 22 February 2010; MoU, Romania, 2nd addendum, 20 July 2010: 8; P-MoU, Romania, 29 June 2011: 12). Additionally, ‘a strong and independent regulatory body for the railway sector’ (P-MoU, Romania, 29 June 2011: 12) was envisaged. Another prescription insists that ‘the regulator has the necessary powers to request data and to take independent decisions on infrastructure charges’ (MoU, Romania, 2nd supplemental, 22 June 2012: 32).

Similarly, EU executives tasked the Italian government to set up ‘the Transport Authority as a priority’ (emphasis added) (Council Recommendation Italy 2013/C 217/11, see also Council Recommendation Italy 2014/C 247/11). Following these prescriptions, national legislators established new transport authorities in Italy (Autorità di Regolazione dei Trasporti) and Romania (Autoritatea pentru Reformă Feroviară), which became operational in 2016. By contrast, the NTA set up by Irish legislators in 2009 had begun operating in 2011; this explains the absence of corresponding NEG prescriptions for Ireland.

The primary objective of these agencies is to ensure competitive neutrality in the transport sector and to bring about organisational change and cost-cutting in state-owned operators so that they behave like private companies. Increasing the power of the infrastructure manager must also be seen as part of the vertical separation between the state-owned rail company and the management of the state-owned infrastructure. Interestingly, the objective was to ‘end political interference in tariff setting and to allow the rail infrastructure company (CFR Infrastructura) to independently determine rail track access charges’ (European Commission, 2013: 51). A euphemism for preventing practices of corruption, the prescription implies that fully liberalised sectors are free of such meddlesome sins, but as Helene Dyrhauge (Reference Dyrhauge2013: 111–112) showed, such processes can be ‘precarious … even when there is no state-owned incumbent’ (see also Crouch, Reference Crouch2016).

Despite the existence of a regulatory agency for network industries, EU executives told the German authorities to ‘strengthen the supervisory role of the Federal Network Agency in the rail sector’ (Council Recommendation Germany 2011/C 212/03). For some time, the EU had been deeply suspicious of the German integrated governance structure in the rail sector and the power of the German incumbent, Deutsche Bahn, to thwart competition and maintain its almost 90 per cent market share in passenger services and almost 80 per cent of the freight market (Dyrhauge, Reference Dyrhauge2013: 45–50). In 2013, 2014, and 2015, NEG prescriptions thus tasked the German government to ‘take further measures to eliminate the remaining barriers to competition in the railway markets’ (Council Recommendations Germany 2013/C 217/09; 2014/C 247/05) generally, and in ‘long-distance rail passenger transport’ in particular (Council Recommendation Germany 2015/C 271/01).

There were also several prescriptions on the subject of PSOs and competitive tendering. The prescriptions that targeted Romania urged its government to ‘continue competitive tendering in the public service obligation contract’ (P-MoU, Romania, 29 June 2011: 12) and to ‘improve the efficiency of public procurement’ (Council Recommendation Romania 2019/C 301/23). The prescriptions for Italy directed its government to promote competition in local public transport services through ‘the use of public procurement … instead of direct concessions’ (Council Recommendation Italy 2013/C 217/11). Uncoincidentally, most of the public transport service contracts between the incumbent stated-owned operator (Ferrovie dello Stato) and Italy’s regional governments expired at the end of the following year. Similar prescriptions were repeatedly issued to the Italian government in 2015 and 2016. The latter was more explicit and stated: ‘take further action to increase competition in … transport … and … the system of concessions’ (Council Recommendation Italy 2016/C 299/01). In 2011, an Italian law that imposed compulsory competitive tendering for all local utilities was repealed through a popular abrogative referendum initiated by the Italian water movement, unions, and other public sector advocates (see Chapter 9). Even so, the EU continued to push its commodifying agenda in the field by repeatedly advocating the adoption of a controversial, national competition law (2015, 2017, 2018, 2019). As most Italian legislators remained confident that EU executives would not dare fine Italy for non-compliance, they resisted implementing the prescription. On 2 August 2022 however, the Italian Parliament adopted the Annual Law No. 118/2022 on Market and Competition as requested, after the EU made its post-Covid resilience and recovery funding conditional upon the execution of its NEG prescriptions, as discussed in Chapter 13.

On the surface, some sector-level governance prescriptions seemed rather innocuous, but on closer inspection a different story emerged. For instance, the Romanian government was urged to adopt ‘a comprehensive long-term transport plan’ and ‘implement’ it (MoU, Romania, 2012: 32; Council Recommendation Romania 2016/C 299/18). Although this might appear to be a perfectly understandable request, it was private capital that benefitted immediately, with US consulting company AECOM, ‘the world’s premier infrastructure firm’, being awarded the €2.2m contract to develop the masterplan (Railway Gazette, 20 April 2012). More ominously however, the adoption of the master plan was ‘an ex-ante conditionality for EU funding of transport infrastructure in Romania during the 2014–20 EU funds programming period’ (European Commission, 2015b: 33). Hence, EU executives used the cohesion funds as a carrot to further a commodification agenda according to Common Provisions Regulation 1303/2013 (Chapter 2) – prefiguring the conditionalities attached to the EU’s post-Covid resilience and recovery funding (Chapter 12). It was by no means a coincidence that such enticement came at a time when the degree of coercion of NEG prescriptions for Romania had significantly diminished, as Romania was no longer involved in any very significant or significant NEG enforcement procedure. Hence, EU executives deployed other mechanisms to ensure compliance, using Romania’s dependence on EU structural and investment funding.

Provider-level governance mechanisms: The clearest form of commodification in the provider-level governance mechanisms category is privatisation. To this end, the MoU of 2010 tasked the Romanian government to take concrete steps towards the privatisation of CFR Marfă (MoU, Romania, 2nd addendum, 20 July 2010: 8), the state-owned rail freight company. The Romanian government in turn put up CFR Marfă for sale, but its privatisation collapsed in 2013 after the winning bidder, Grup Feroviar Roman, pulled out of the deal. EU executives nonetheless largely succeeded in turning freight transport into a private affair, as the opening of the sector to competition from private rail and road operators reduced CFR Marfă’s market share to less than 20 per cent (ADZ.ro, 7 July 2021).

As documented in Chapter 7, EU executives tasked Italy to ‘swiftly and thoroughly implement the privatisation programme’ (Council Recommendation Italy 2015/C 272/16). Although this prescription did not mention Trenitalia’s parent company, Ferrovie dello Stato, explicitly, the intended target became clear shortly afterwards when the Italian government announced its plan to sell up to 40 per cent of the company (Financial Times, 18 November 2015). This proposal, however, provoked mayhem, not only within its workforce but also within its senior management, and led to the resignation of the entire company board, as its members could not agree on how to privatise the railway, thereby stalling the government’s privatisation plans. This, however, did not prevent Italy’s state-owned railway company – like its German (DB) and French (SNCF) counterparts – from buying up privatised rail companies elsewhere in the EU (Gevaers et al., Reference Gevaers, Maes, Van de Voorde, Vanelslander, Finger and Messulam2015).

Other than privatisations, NEG prescriptions promoted the corporatisation of state-owned rail operators. EU executives tasked the Romanian railway management company, CFR Infrastructura, ‘to complete the present business plan with market-oriented information’ (MoU, Romania, MoU, 2nd supplemental, 22 June 2012: 32; P-MoU, Romania, 29 June 2011: 12). The following year, 2013, they tasked the Romanian government to continue their ‘corporate governance reform of state-owned enterprises’ in the ‘transport sector’ (Council Recommendation Romania 2013/C 217/17). With progress being too slow and ‘insufficient’ (European Commission, 2014b: 4), EU executives urged the government yet again to accelerate the corporate governance reform of state‐owned enterprises in the ‘transport sectors and increase their efficiency’ (Council Recommendation Romania 2014/C 247/21). As outlined above, increasing efficiency meant reducing costs through either labour shedding or line closures, both of which negatively affected the quality of public services. Even so, the NEG prescriptions echoed this approach in 2016 and 2019.

The 2016 prescription for the Italian government tasked it to implement ‘all necessary legislative decrees’, namely, those ‘reforming publicly-owned enterprises’ local public services’ (Council Recommendation Italy 2016/C 299/01). The latter included local public transport companies, whose ‘inefficiency’ was identified as being ‘particularly critical’ (European Commission, 2015a: 57). Unsurprisingly, publicly-owned (local) enterprises were targeted again by NEG prescriptions in 2019. In response, the Italian government introduced a new legislative framework that ‘aims to regulate systematically state-owned enterprises in line with the principles of efficient management, protection of competition and the need to reduce public expenditure’ (Commission, Country Report Italy SWD (2016) 81: 66). Furthermore, the government of Prime Minister Renzi announced that the number of publicly owned enti locali would be significantly reduced from 8,000 to 1,000 (Il Foglio, 13 January 2016). As the national government tasked its regions with the regulation of its local public transport and water services, different regional governance patterns emerged (Di Giulio and Galanti, Reference Di Giulio and Galanti2015). Nonetheless, even the centre-left government of Tuscany, once a heartland of Italian communism, awarded the operation of all public transportation services in the region in a single bundle to the French RATP Group ‘with subsidies amounting to €4bn’ (2015: 9). This put Tuscany’s municipal public transport providers (e.g., the Azienda Trasporti dell’Area Fiorentina: ATAF) out of business.

Prescriptions on Users’ Access to Services

As outlined above, several NEG prescriptions explicitly targeted the provisions of transport services. By contrast to those on water (Chapter 9) or healthcare services (Chapter 10), EU executives did not issue any NEG prescription that targeted primarily users’ access to public transport services, either on cost-coverage mechanisms (user charges) or on coverage levels (scope) of public services. That said, the constraints caused by the general NEG prescriptions on the curtailment of public spending (Chapter 7) or on the closure of unprofitable lines (discussed above) did affect users’ access to public transport services, albeit indirectly. Take Ireland for example. The Irish government radically reduced its subsidies for public transport providers. In the case of Dublin Bus, its public service obligation subsidy decreased from an already comparatively low figure of 29 per cent in 2009 to 20 per cent in 2015 (Unite, 2016), resulting in substantial ticket price increases (Irish Times, 19 October 2018).

NEG: Commodifying Public Transport Services by New Means

In sum, the transport sector was the subject of numerous NEG prescriptions. Most of them were qualitative in character and all of those went in a commodifying policy direction. By contrast, there was a dearth of quantitative prescriptions on the curtailment of spending on public transport services, save that issued in the singular to Romania in 2011/2. This finding is hardly surprising however, as the curtailment of public expenditure usually occurs at intersectoral level (Chapter 7). The exception here is healthcare, which constitutes a significant chunk of government expenditure (Chapter 10). There were also some quantitative prescriptions relating to resources, which pointed in a decommodifying direction. This suggests that some prescriptions were motivated by an alternative policy rationale, which does not fit the dominant commodification policy script that informs all qualitative NEG prescriptions on transport services issued across all countries from 2009 to 2019. We come back to this in this chapter’s conclusion. Before that, however, we discuss EU executives’ qualitative NEG prescriptions on transport services, which are striking as they repeatedly went beyond the acquis of EU law in the field, most explicitly by pushing a privatisation agenda.

Sector-level governance as a category featured most regularly, and these prescriptions chimed with the evolving rail acquis, which has been slow and tortuous. In a sector bedevilled by transposition deficits, regulatory heterogeneity, and (unsuccessful) infringement proceedings (section 8.2), the shift to the NEG regime provided EU executives with an opportunity to put the creation of the European rail market back on track. Sector-level prescriptions included enhanced independence for the regulator and the infrastructure manager from the publicly owned rail company and the national government; this technocratic fix is synonymous with ending political interference. For it to succeed, partisan, democratic decision making must be portrayed ‘as slow, corrupt, and ultimately irrational’ (Radaelli, Reference Radaelli1999: 47).

For the Commission, the German rail market is critical with regard to creating the single European rail market, as this ‘has an impact on the whole European railway system, given Germany’s central geographical position’ (Council Recommendation Germany 2012/C 219/10: Recital 15). However, the Commission remained frustrated with the lack of competition in German rail and rather suspicious of its governance structure, not least regarding financial transparency and cross-subsidisation. Deutsche Bahn has an integrated governance structure, which the Commission considered an obstacle to competition. Pursuing a parallel two-pronged approach vis-à-vis Germany, EU executives repeatedly issued prescriptions for the elimination of barriers to rail competition, with the Commission on a constant basis lamenting the lack of ‘progress in removing the remaining barriers to competition in the railway markets’ and identifying the ‘existing legal framework’ as ‘impeding competition’ (Commission, Country Report Germany SWD (2017) 71: 48). The Commission’s regular misgivings reflect the weak coercive power that the German NEG prescriptions were having. For this reason, the Commission was obliged also to continue making use of its traditional governance powers by law and through court proceedings, as outlined in the next subsection. Even so, the clearly commodifying bent of the NEG prescriptions issued to Germany on the provision of transport services is remarkable, as it confirms the existence of an overcharging commodifying policy agenda targeting all countries, irrespective of their location in NEG’s policy enforcement regime.

Romania and Italy, on the other hand, not only received prescriptions that went deeper than sectoral level governance but were also obliged to take them much more seriously. Both countries created independent transport authorities with substantial regulatory powers to further the liberalisation process. Ireland would have been obliged to take such prescriptions seriously, given its location in NEG’s policy enforcement regime. However, there was no need for them as Irish legislators had already set up the NTA in 2009.

EU executives also tasked the Romanian government to enhance the regulatory powers of the independent infrastructure agency in relation to its charges to railway, metro, or tram companies for their use of the rail network. Infrastructure charges are one resource, along with state subsidies, to finance rail infrastructure but have been ‘the subject of serious political and economic debates and decisions since the very origin of railways’ (emphasis added) (Messulam and Finger, Reference Messulam, Finger, Finger and Messulam2015: 323). More importantly, they remain ‘one of the main barriers’ to implementing commodifying rail reforms in Europe (2015: 325). The drafters of Directives 95/19/EC and 2001/14/EC tried to resolve the rail access charge issue, but the final directives ‘failed to deliver’ (2015: 325). To this end, the EU’s shift to the NEG regime provided EU pro-market actors with an opportunity to resolve this question in their favour. Whereas the European Parliament and the Council of transport ministers had been able to curb the commodifying bent of the Commission’s earlier universal legislative proposals in the field, typically in response to transnational strikes and demonstrations triggered by the Commission’s proposals (see below), their country-specific NEG prescriptions enabled the Commission and Council of finance ministers to pursue a commodification agenda that went beyond the transport acquis.

In sum, the shift to the NEG regime enabled EU executives to cajole reluctant member states – particularly those subject to constraining prescriptions – into accepting the Commission’s preferences, which EU legislators often watered down in the ordinary legislative procedures pertaining to transport laws. It is unequivocal that NEG prescriptions pursued the Commission’s long-standing commodifying policy preferences, namely, vertical separation in rail, regulatory independence, tendering for PSOs in transport services rather than direct concessions, and increased competition between transport providers. In other words, NEG provided EU executives with a new avenue to commodify transport services. Where NEG prescriptions’ coercive power was weak or began to wane however, EU executives continued to use the ordinary EU legislative procedures by law to advance their objectives.

EU Laws on Transport Services after the Shift to NEG

After most member states exited the corrective arms of the NEG regime, EU executives began to use another power resource to enforce their country-specific prescriptions, namely, the ex ante conditionality of EU cohesion funding (Chapter 2). This was the case in Romania, where EU executives used the carrot of EU cohesion payments (rather than the stick of financial sanction) to further their policy agenda in the transport sector. This enforcement power resource, however, works only for countries that depend on EU cohesion funding. Although EU executives also tasked the German government to reform the existing governance framework for public transport to increase competition, the weak constraining power of NEG prescriptions in this case meant that Germany could largely ignore them. To advance its policy objectives, the Commission therefore continued to use its ordinary legislative powers as initiators of EU laws as well as its legal powers in state aid and infringement proceedings.

In 2011, the Commission released another White Paper on transport (COM (2011) 144 final), which set the making of a true internal market for rail services as a priority. To that end, it proposed the structural separation between infrastructure management and service and the mandatory award of public service contracts under competitive tendering for public passenger transport. Already in 2010, the Commission had proposed replacing Directive 91/440/EEC with a recast directive, which sought to ‘avoid distortion of competition and preferential treatment of the incumbent’ by strengthening the independence of regulatory bodies from partisan politics and in particular the transport ministry (Dyrhauge, Reference Dyrhauge2013: 86). Importantly however, the final Recast Single European Railway Directive (2012/34/EU) of the European Parliament and Council ‘did not require organisational separation, thus complete vertical separation was not necessary’ (Dyrhauge, Reference Dyrhauge2013: 86). Despite this setback, the Commission continued to pursue its commodifying objectives, not only through NEG prescriptions but also by proposing a fourth package of EU railway laws.

The 2016 fourth railway package is the Commission’s most ambitious to date, as it aimed to introduce vertical separation and competition in the passenger market, including rail services under PSOs. Regarding governance structure, a blocking Council minority of national transport ministers (including Austria, Germany, Italy, and France) resisted vertical separation along with Community of European Railways (CER) and European transport workers’ unions (Scordamaglia and Katsarova, Reference Scordamaglia and Katsarova2016). The CER (2011) argued that a one-size-fits-all model for all countries would be unrealistic given the variation between them in structural characteristics. In addition, competition would work no better with vertical separation than with a holding company. The final package adopted by the Parliament and Council thus allowed for vertically integrated rail companies but introduced Chinese walls to restrict financial flows between the infrastructure manager and the rail operator in the overarching holding company. According to the package’s Compliance Verification Clause, the Commission can prevent rail companies that are part of a vertically integrated structure from operating in other member states if fair competition in their home market is not possible.

The ETF (2014) feared that cherry-picking lucrative contracts would lead to the neglect of less profitable rail routes and argued that direct award should remain the member states’ prerogative. To this end, the ETF (2014) petitioned members of the European Parliament (MEPs) and transport ministers to curb the Commission’s enthusiasm for competitive tendering by respecting the freedom of choice guaranteed under the PSO Regulation (1370/2007) discussed in section 8.2. Regarding the outcome, the ETF was pleased that governments had not accepted the Commission’s ‘dogmatic’ approach (ETF, 2015a), although concerns about social and employment conditions remained. The legislative amendments of the European Parliament and the Council of transport ministers to the fourth railway package somewhat curbed the commodification bent of the Commission’s initial legislative proposal, but this prevented neither the Commission and the Council of finance ministers from issuing NEG prescriptions that went further than the EU’s legal acquis (as discussed above), nor the Commission from using its significant powers as an enforcer of EU law to advance its aims.

In March 2011, the Commission conducted dawn raids on Deutsche Bahn offices. However, the latter brought a case to the CJEU, which deemed the Commission’s actions to be illegal.Footnote 9 It was against this backdrop that the Commission proposed its fourth package of EU railway laws. As mentioned above however, a Franco–German alliance in the Council, coupled with European Parliament lobbying by the CER and the ETF, thwarted the Commission’s push for ‘radical policy change’ (Dyrhauge, Reference Dyrhauge2022: 866). In 2017 however, the CJEU condemned Germany for failing to take all the necessary measures to ensure the transparency of accounts between Deutsche Bahn and its subsidiaries,Footnote 10 some of which operate in other member states. Hence, in the German case, policy change resulted from a CJEU ruling rather than NEG prescriptions or the adoption of new EU laws.

Finally, the Commission used its dual role as investigator and decision maker in EU competition law to advance its commodification agenda. This happened in the case of the privatisation of the freight train company CRF Marfă, which failed despite the MoU-related NEG prescription discussed above. In turn, the Commission brought CRF Marfă to the brink of insolvency when it ordered it to pay back the €363m of state aid that it had received, in agreement with the Council and the IMF, to facilitate its privatisation (Commission Decision 2021/69, Recital 107).Footnote 11

8.4 EU Transport Governance and Transnational Countermovements

From the pre- and post-2008 scenarios outlined above, it is clear that the commodification of transport services has been a long-standing policy preference of the Commission. However, the more there was a public service aspect, the more commodification became contentious; this explains why Mario Monti (Reference Monti2010) described the slow pace of EU service liberalisation as a ‘persistent irritant’. This reflects the resistance by anti-commodification forces, including transport workers’ unions and social movements (Turnbull, Reference Turnbull2000, Reference Turnbull2010; Gentile and Tarrow, Reference Gentile and Tarrow2009; Hilal, Reference Hilal2009; Fox-Hodess, Reference Fox-Hodess2017). Understanding this resistance and the form it takes is important, as ‘the extent to which non-capitalist space is incorporated also depends on the level of resistance against this expansion’ (Bieler and Morton, Reference Bieler and Morton2018: 41). In this section, we discuss transport workers’ resistance to EU prescriptions and their consequences.

Most European transport workers are represented at EU level by the ETF, especially in the public railway sector (Traxler and Adam, Reference Traxler and Adam2008). The ETF’s raison d’être, since 1999, is, simply put, to add the argument of force to the force of argument (Turnbull, Reference Turnbull2010). This is done by combining outsider strategies (European demonstrations and transnational strike actions) with insider strategies (lobbying MEPs and European transport ministers) that seek to protect transport workers’ interests and to prevent a further commodification of transport services. To date, transnational protest actions by European transport workers have made a difference, albeit to varying degrees, depending on the transport modality in question.

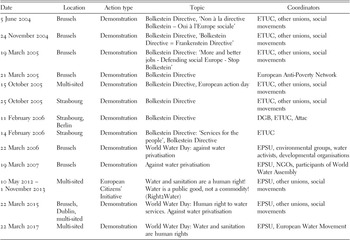

Table 8.3 presents a list of transnational transport-related social and economic protests politicising the EU governance of transport services (Erne and Nowak, Reference Erne and Nowak2023). The list documents the capacity of the ETF, the International Transport Workers’ Federation (its global sister organisation), and transnational grassroots alliances of European dockworkers to orchestrate transnational strikes and days of action against commodifying EU interventions. The apogee is undoubtedly ‘the war on Europe’s waterfront’ where docker strikes were ‘timed to coincide with Council deliberations on the [Port Services] Directive’ (Turnbull, Reference Turnbull2010: 341), but other transport modalities have also been defended against EU liberalisation attempts, albeit to a lesser degree (Hilal, Reference Hilal2009; Crochemore, Reference Crochemore2014; Harvey and Turnbull, Reference Harvey and Turnbull2015; Golden and Erne, Reference Golden and Erne2022; Szabó, Golden, and Erne, Reference Szabó, Golden and Erne2022). This can be explained not only by the Commission’s unwavering bent for the commodification of the sector but also by its incremental liberalisation strategy, which targeted each modality one by one (Héritier, Reference Héritier1997; Szabó, Golden, and Erne, Reference Szabó, Golden and Erne2022). Whereas the transnational strikes of dockers (Fox-Hodess, Reference Fox-Hodess2017) – and to some extent also railway workers (Hilal, Reference Hilal2009; Crochemore, Reference Crochemore2014) – were quite effective, other transnational union campaigns were less successful, including those politicising the EU public procurement directives in the 2000s, as ‘the organisation of strikes [or demonstrations] was [either] not considered [or failed to materialise]’ (Bieler, Reference Bieler2011: 175).

Table 8.3 Transnational protests politicising the EU governance of transport services (1993–2019)

| Date | Location | Action Type | Topic | Coordinators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 March 1994 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against deregulation of the European air transport sector | ETF |

| 19 November 1996 | Brussels, Italy | Strike, demonstration | Against white book on transport | ETF |

| 9 June 1997 | Multi-sited | Strike | International Day of Action in road transport | ETF/ITF |

| 18 June 1998 | Luxembourg | Demonstration | Against white book on transport | ETF |

| 8 September 1998 | Multi-sited | Strike | International Day of Action in road transport | ETF/ITF |

| 23 November 1998 | Multi-sited | Strike, demonstration | Against EU plans for rail privatisation | ETF |

| 5 May 1999 | Multi-sited | Strike | International Day of Action in road transport | ETF/ITF |

| 29 March 2000 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Against first rail package | ETF |

| 1 October 2000 | Luxembourg | Demonstration | Against Working Time Directive for road transport | ITF/ETF |

| 29 March 2001 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | International Day of Action in support of rail safety | ITF/ETF |

| 25 September 2001 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against proposed port package | ETF |

| 15 October 2001 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | International Day of Action on road transport | ETF/ITF |

| 6 November 2001 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against proposed port package | IDC |

| 26 March 2002 | Brussels | Demonstration | International Day of Action of railway workers | ETF/ITF |

| 14 June 2002 | Strasbourg, multi-sited | Strike | Against port package | IDC |

| 19 June 2002 | Multi-sited | Strike | Air traffic controllers against a single European airspace | ETF |

| 17 January 2003 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against port package | ETF |

| 17 February 2003 | Brussels | Demonstration | Against port package | ETF |

| 10 March 2003 | Strasbourg, multi-sited | Strike, demonstration | Against port package | ETF/ IDC |

| 14 March 2003 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | International Day of Action of railway workers | ETF/ITF |

| 18 March 2003 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against EU plans towards privatisation of rail freight transport | Various |

| 8–12 and 29 September 2003 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against port package | ETF |

| 13 October 2003 | Multi-sited | Strike, demonstration | International day of road transport | ETF/ITF |

| 19 November 2003 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against port package | ETF/IDC |

| 31 March 2004 | Lille | Demonstration | European Day of Action against the liberalisation of railways | ETF |

| 21 November 2005 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against port package | ETF |

| 11–12 January 2006 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against port package | ETF |

| 16 January 2006 | Strasbourg | Demonstration | Against port package | ETF |

| 2 March 2006 | Multi-sited | Strike | European railway strike against meeting of EU traffic ministers | ETF |

| 13 November 2008 | Paris | Demonstration | Against rail privatisation | ETF |

| 5 October 2009 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Against (weak) EU safety regulations | ETF/ECA |

| 13 April 2010 | Lille | Demonstration | Against liberalisation and privatisation of railways | ETF |

| 24 May 2011 | Brussels | Demonstration | European Day of Action against Recast Directive on railways | ETF |

| 8 November 2011 | Multi-sited | Strike, demonstration | European Day of Action against liberalisation of railways | ETF |

| 9–13 January 2012 | Lisbon, multi-sited | Strike, demonstration | Solidarity with Portuguese dockworkers | ETF/IDC |

| 24 September 2012 | Brussels | Demonstration | Against social dumping in the road transport sectora | ETF |

| 9 October 2012 | Brussels | Demonstration | Against social dumping in the road transport sectora | ETF |

| 5 November 2012 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Against airport package | ETF |

| 29 November 2012 | Lisbon | Demonstration | Against plans by the Portuguese government to change labour rules | IDC |

| 22 January 2013 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Against (weak) EU safety regulations | ETF/ECA |

| 12 June 2013 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against a single European airspace | ETF |

| 9 October 2013 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Railway workers against fourth railway package | ETF |

| 10 October 2013 | Brussels, multi-sited | Demonstration | ETF Road Transport Section against social dumping | ETF |

| 14 October 2013 | Brussels | Demonstration | Against package on Single European Sky | ETF |

| 29–30 January 2014 | Multi-sited | Strike | Against package on Single European Sky | ETF/ATCEUC |

| 4 February 2014 | Multi-sited | Strike | Solidarity with Portuguese dockworkers | ETF/IDC |

| 25 February 2014 | Strasbourg | Demonstration | Against fourth railway package | ETF |

| 3 May 2014 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | European protest day of truck driversa | Various |

| 8 October 2014 | Luxembourg | Demonstration | Against fourth railway package | ETF |

| 14 September 2014–14 September 2015 | Online | ECI | Fair Transport Europe – equal treatment for all transport workers | ETF |

| 5–11 October 2015 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Global rail and road action week, including opposition to the EU’s planned fourth railway package | ITF/ETF |

| 13–14 January 2016 | Sines | Demonstration | Precarious labour in the port of Sines | IDC |

| 7 July 2016 | Multi-sited | Strike | Global day of docker actiona | IDC/ITF/ETF |

| 5 December 2016 | Brussels | Demonstration | Against fourth railway package | ETF |

| 12 December 2016 | Strasbourg | Demonstration | Against fourth railway package | ETF |

| 10 March 2017 | Multi-sited | Strike | Solidarity with Spanish dockworkers | IDC, ITF |

| 26 April 2017 | Brussels | Demonstration | End social dumping in road haulage | ETF |

| 17 May 2017 | Strasbourg | Demonstration | Campaign for a social Road Initiative | ETF |

| 8 June 2017 | Luxembourg | Demonstration | Against road package | ETF |

| 9–11, 19, and 29 June 2017 | Multi-sited | Strike | Solidarity with Spanish dockworkers | IDC |

| 20–24 November 2017 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Action on Posting of Workers Directive | ETF |

| 29 May 2018 | Strasbourg | Demonstration | Against mobility package | ETF |

| 2 October 2018 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Working conditions at airports | ETF |

| 3 December 2018 | Brussels | Demonstration | Working conditions for drivers | ETF |

| 7–9 January 2019 | Multi-sited | Demonstration | Action for fair mobility package | ETF |