In “Panels of an Urban Salon Landscape,” a Chinese poet captures a memorable scene of liberation featuring a swaggering foreign “predator” and a Chinese girl riding in a speeding Jeep. The poem ends with a sour statement: “The world’s freedom and peace now depend on this crowd,” a satire of both the proclaimed American geopolitical missions in the world and the Chinese female “peacemakers” who fraternize with foreign soldiers.2 Among all the frictions involving GIs, ranging from daily traffic accidents to brutal murders, sexual relations with Chinese women triggered the strongest anti-American sentiments within Chinese society.3 Conservatives condemned women for liaisons with American soldiers and acting like whores. The infamous Peking rape incident sparked massive protests and drew an outpouring of support among urban residents, even from some government officials. It astonished many contemporary observers that a single rape case could convulse the entire nation overnight. If the first American Volunteer Group, affectionately dubbed the “Flying Tigers,” exemplified the altruistic American heroes during the war, drunken marine rapists became the symbol of American imperialism. Through the injured and maligned bodies of Chinese women, the global US military empire became deeply entangled with China’s local politics.

Like other occupied areas, actual and perceived sexual relations between local females and American soldiers often caused social animosity and even vengeful violence. Chinese discussions of women mixed racial, cultural, and sexual anxieties and were formulated along class lines. Critics were mostly concerned about preventing “respectable” middle- and upper-class women from falling into disrepute or from suffering violence, whereas lower-class prostitutes were ignored or seen as a tool to protect the “purity” of the nation.4 But the Chinese case stands out even more by virtue of the central role occupied by elite women, involving both romance and violence. The Chinese controversy began as a vibrant debate over “Jeep girls,” referring to women who socialized, sometimes intimately, with American soldiers during and after WWII.5 The contemporary translation “Jeep girls” combines the “girl,” a social and representational category “largely delinked from biological age,”6 and “Jeep,” a multivalent symbol, as discussed in the previous chapter, of American military victory, industrial and commercial success, and white masculinity. The early discussion, centering on modernity and Westernization, attracted a diverse group of conservatives, liberals, leftists, feminists, and the women themselves. Prevalent hostility toward Jeep girls continued the attacks on “modern women” that had occurred in earlier decades and was deeply embedded in the threats they posed to masculinity, patriarchal gender relations, and hegemonic nationalism. After the Peking rape incident, however, the multivalent debate swiftly gave way to a predominantly nationalist message of reclaiming sovereignty against American imperialism, accompanied by nationwide anti-American demonstrations. In this hypernationalist environment, little space remained for the modern Jeep girls, and Chinese women existed only as whores to be condemned or victims to be defended.

This chapter foregrounds the key role of gendered nationalism in Sino-US relations. Simmering beneath the national alliance and harmonious relations were long-standing dissatisfactions with and resentments toward American superiority since wartime, from the highest levels of the Chinese leadership to ordinary soldiers and civilians.7 As the nation recovered territories in former Japanese-occupied areas and rejuvenated itself after eight years of devastating war, Chinese elites were eager to reclaim both national sovereignty and individual masculinity. Heightened nationalism clashed with the hypermasculine American military over actual and symbolic territoriality.

Modern Women or Parasitic Whores: The Jeep Girls Debate

How proud the Jeep girls, jumping onto the Jeeps, holding tall allies in their arms, and entering grand ballrooms and exquisite bars with their clicking high heels. How lucky the Jeep girls, opening their fat wallets filled with American dollars, perfumes and powders, authentic chocolates and chewing gums brought by airplanes. Every one of them has become Westernized and now looks at the Chinese people the way Westerners look at them, with shifty eyes beaming arrogant foreign airs. Everything is so full of an exotic atmosphere that they forget, forget about their black hair.

The Chinese epithet “Jeep girls” began to circulate during the war when women were seen riding around in Jeeps with GIs, and it was later expanded to describe all types of women who were perceived to have intimate relationships with American soldiers. Contemporaries divided the Jeep girls into three categories based on socioeconomic differences. At the bottom of the social ladder were destitute prostitutes who operated in registered or underground brothels, facing the precarities of economic exploitation, police harassment and arrest, physical violence, and venereal disease. The Nationalist Government had long maintained an inconsistent and ineffective policy toward prostitution, while local governments adopted a variety of approaches, which often had conflicting objectives of revenue generation, morality, and public health.9 Like elsewhere, prostitution was already rampant during the war near American barracks.10 Upon Japan’s surrender, the influx of American military personnel from wartime bases in southwest China to major cities previously occupied by the Japanese contributed to a boom in the sex and entertainment industries. In Shanghai, known as the “Paris of the East,” prostitutes filled the streets and wandered around the hostel buildings. Writer Robert Payne, then serving as a cultural attaché to the British embassy, had his room door suddenly opened from outside one day, revealing a girl and a hotel coolie, who pursued him with relentless questions: “Want girl?” “Want boy?” “You American?”11 Lou Glist, a US Army officer stationed in Shanghai, observed that White Russians were highly sought after “in a world where white women were scarce.” The more fortunate among them became GI companions, while those less fortunate in appearance or age turned to prostitution.12 Seasoned Chinese journalist Guo Gen gave a detailed account of Beijing brothels servicing American soldiers. Suzhou Hutong in the downtown area had been a prospering district for international whorehouses with a history tracing back to the late Qing period; it now became “a heaven for the ‘Allies,’” attracting a diverse range of prostitutes, including White Russians, Japanese, Koreans, and an increasing number of Chinese rural women who were war refugees. The cost per service in 1946 was said to be about one US dollar, while the girls only ended up with 30 percent after paying pimps, interpreters, and madams. When the local police or the US military tightened rules against brothels, these women often resorted to street prostitution instead. Soon they all became “Mary” in the words of a “GI Joe,” who found it difficult to tell them apart or pronounce their Chinese names.13

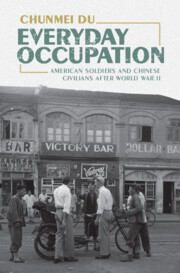

A second type worked in cafes, restaurants, cabarets, nightclubs, and hotels, providing entertainment and occasionally sexual services (see Figure 4.1). Many were hired by the sites to attract customers or increase alcohol sales. With some social and cultural capital, such as varying levels of English-language proficiency, dance skills, and familiarity with modern leisure, these women often accompanied GIs to entertainment sites, creating a public spectacle, and appeared in popular souvenir photos that soldiers sent home. Postwar tabloids reported former dance stars, opera singers, and actresses becoming Jeep girls.14 The women in this group were not necessarily destitute, but economic interests remained central to their relationships with GIs, and their activities were a highly visible part of the postwar urban economy and tabloid scene. While mocked for their declining beauty, income, and social status, these former “social butterflies” also appeared fashionable and even enviable posing in their Western-style dresses and accessories, gifted by generous GIs.

Figure 4.1 American sailors in intimate contact with hostesses at the Diamond Bar in Shanghai, 1949.

The third group included upper-middle-class women whose motivations ranged from financial benefit to the lofty idea of “service to the nation.”15 During the war, English-speaking college students worked for the American military as clerks, translators, and volunteers. Members of women’s organizations, often including government officials’ wives and daughters, facilitated the Allied forces’ operations and their daily lives in China by socializing with officers and soldiers.16 Some of the earliest marriages between GIs and Chinese women resulted from these interactions.17 In addition to official parties, American-educated notables hosted home gatherings and arranged blind dates for the army men.18 After the war, the Nationalist Government continued to encourage elite women to host or attend victory parties to ensure that American soldiers would find China a hospitable place. The US military also held regular social events in collaboration with local organizations like the YWCA and War Area Service Corps (see Figure 4.2). As the number of “Jeep girls” increased, the group’s composition and perception evolved, encompassing more women who did not fit the stereotype of being prostitutes from the lowest rungs of society.

Figure 4.2 American soldiers socializing with Chinese women in postwar Qingdao. MCHD.

In addition to a clear class divide, regional differences existed in the distribution of Jeep girls, with more Westernized cities being seen as more open to such relations compared to conservative places. As one journalist teased, Allied soldiers in Beijing must be so jealous of their comrades in Shanghai, who never ran out of female companions.19 Variations notwithstanding, the “Jeep girl” label carried a negative connotation and even became a social stigma. Jeep girls were subject not only to the voyeuristic gaze, media scrutiny, and state control, but also to actual violence. Women seen in public with GIs were rumored to be prostitutes, regardless of the true nature of their interactions, and “the venom of the crowd” was usually “leveled at the girl,” who was insulted, threatened, and even attacked.20 In April 1945, an angry crowd in the wartime capital of Chongqing threw rocks and spat at women visiting cafes and restaurants with American soldiers, pulled their hair, and hurled curses at them.21 Mobs in Chongqing, Chengdu, Kunming, and Guiyang targeted women accompanying GIs in public, resulting in Chiang Kai-shek’s order to ban local newspapers’ “agitative reporting of ‘Jeep girls.’”22 In November 1946, outside a Shanghai cafe, a US Navy soldier and his Eurasian girlfriend were attacked by a local crowd wielding blackjacks and clubs. The assault occurred after the couple refused to buy flowers from two flower girls. The girlfriend suffered abrasions and contusions to her face and head, while the soldier only had minor contusions. According to him, the mob included both the “coolie class and upper class Chinese.” The two Chinese police on the corner who saw the incident “made no attempts to help,” and even the Chinese MP was “taking sides with the flower girls.”23 In postwar Beijing and Tianjin, American servicemen and Chinese clients, including armed policemen, battled over dance hostesses.24 The sentiment was clear and simple, as one Chinese officer declared: “I don’t want American soldiers to go with Chinese girls!”25 In 1946, in response to local animosities, General Chen Cheng, chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, allegedly banned Chinese women from riding in American Jeeps.26 The occasional street fights certainly encapsulated the mounting social tensions and made headlines. However, what occupied center stage in the Chinese media was the wholesale malignment of the so-called Jeep girl phenomenon, pertaining to “respectable women’s” willingness to fraternize with the Americans.

One distinctive social and representational category – college students – was singled out as the primary target of media attacks.27 Using various Chinese terms, such as “female college students,” “lady of noble birth,” and “campus belle and socialite,” commentators debated why students from affluent families would aspire to become Jeep girls. One critic claimed that “money is secondary; it is really vanity that harmed them.”28 Another pointed to the corrupting effects of American commodities and lifestyles on Chinese morals; they were “even worse than the Soviet looting of Manchuria.”29 Other lines of criticism were more explicit in unveiling Chinese men’s mixed sexual and racial anxieties over those “red-haired wild beasts.”30 One described educated Shanghai women’s attraction to Americans as “just like an iron nail towards a magnet” to explain why “the US military has conquered women all over the world,” while another retooled a classical poem to mock female students for “spreading their legs wide open.”31 The lure of GIs, in one author’s summation, was both physical and material, ranging from the exotic features of curly hair, blue eyes, pale skin, blond body hair, strong limbs, and “tall, big, manly, strong” physique to the material luxuries of perfume, skin powder, lip balm, and US dollars.32

These conservative reactions highlighted the perceived danger of the Jeep girl phenomenon: cultural contamination mixed with sexual and racial conquest. One author wryly remarked that mixed-race children, the so-called Jeep babies, were in such demand that charities in Chongqing posted adoption advertisements to make a profit.33 Another cartoon portrayed a street “auction” scene, in which a Jeep full of babies was surrounded by an enthusiastic crowd, with a front sign proclaiming “‘authentic American breed’ costs U.S. $100 per head.”34 In reality, the fates of biracial babies could also be grim as they were often subjected to mistreatment by local families, regardless of whether a marriage had taken place. In one extreme case, a twenty-month-old infant suffered a severe beating at the hands of a relative on his mother’s side, while his GI father returned home after being discharged and refused to acknowledge the child or send any financial support.35

Similar cultural fears and sexual anxieties also existed in other parts of the world, where men resented the sexual rivalry presented by American soldiers, who were deemed “overpaid, oversexed, and over here!”36 Moreover, these hostile attitudes continued the critiques of “girl students” and “modern women” that had been made in earlier decades, reflecting a persistent Chinese discomfort with rapid Westernization and male intellectuals’ identity crisis and anxiety over educated women.37 While lower-class courtesans were expected to be sexually available, it only became a scandal when “good girls” were in danger of corruption. Late Qing regulators tried to control female students’ uniforms with increasing stringency, and critics warned that there was little distinction between girl students looking like prostitutes and prostitutes who dressed like students to incite licentiousness.38 In 1928, a group of students from Ginling Women’s College who visited a cruiser and danced with British soldiers on board were condemned by outraged male students from nearby Nanking University and the public for engaging in a type of lewd, immoral act and causing national humiliation.39

In the 1930s, male Chinese elites criticized modern women’s superficiality, using terms such as “vain,” “parasitic,” “indulgent,” and “degenerated.”40 Assisted by social conservatives, Chiang Kai-shek’s New Life Movement discouraged and even penalized women who “engaged in the ‘negative’ and ‘evil’ endeavours of modernity, such as wearing Western-style clothes, purchasing foreign products, or exposing parts of their bodies in public,” and promoted a Chinese model of “frugal modernity.”41 As self-appointed enlightened guardians of women and advisors of the nation, reformist intellectuals were concerned with the moral attributes of modern women and saw it as their responsibility to guide women’s morals, behaviors, and emancipation.42 Communists were also critical of what they considered the individualist lifestyle and materialist consumption rampant in Western capitalist society. Their agenda was to transform these women from “parasites of society” into active participants in political movements, achieving true liberation for women. During the war, these different groups converged in their condemnation of the vices of modernity, material pleasure, and moral degeneration. In their view, at a time of national salvation, women should first be patriotic citizens. The representational image of Jeep girls resembled modern girls’ shallow appearance, frivolous behavior, and immoral inner qualities. But their scandalous consumption of luxury foreign goods, now unaffordable or inaccessible to most citizens, made them even worse for the national betrayal.

Conservative attacks were quite effective in stigmatizing “Jeep girls,” a label that now bore a strong association with prostitutes. But not all critiques were denunciations of Jeep girls alone, and a more nuanced analysis reveals complexities in the critical voices. A fictional admirer wrote “A Farewell Letter to a Jeep Girl” in a Shanghai weekly. The piece looks like a mockery of the girl, who is full of “exotic stench,” kissing an ugly, toad-like foreign soldier and thereby losing the face of “our citizens of the big nation.” But quickly the reader realizes that the piece is actually satirizing the Chinese man, who, out of jealousy, threatens to take his own life if the girl does not reply to his letter. He then declares that from now on he will become decadent, and consequently China’s revolution will not succeed.43 An imaginative essay from another Shanghai tabloid begins with a girl’s worry that her Allied “darling” is being confined by the MP for his late return to the barrack. But her “love letter” quickly moves on to ask whether he has received this month’s pay, as he has promised to buy her more perfume. The letter ends with her Chinglish note, “Tomorrow I still wait you at the door of Cathay Hotel.”44 In both cases, the main target of mockery is in fact the man.

Modern urban men had long expressed paradoxical feelings toward Chinese women, from hidden voyeuristic desires for new female students in the late Qing period whose new dress and public presence they also criticized, to the mixture of longing for and fear of the modern girl in the 1920s and 1930s.45 Visual representations act out imaginary social scenes and capture such ambivalences. In Chinese illustrations, Jeep girls appear Westernized in their clothing, hairstyle, makeup, and accessories, as if they adorn the latest Hollywood movie poster. Even their physical features are often exaggerated, mimicking the perceived sexy white body.46 Like the modern Chinese women of earlier decades, they invoke sensational spectacles with their scandalous dress, bodies, and behavior in public, with their seductive looks, feet far apart, arms extended, and body exposed.47 These spectacles are enhanced by the objects that women carry, from high heels and sharp American uniforms to the attendant Jeep and GI. Jeep girls are depicted not in the distant background, but rather occupy the center of the picture, often looming larger than men (see Figures 4.3 and 4.4). The Jeep girl is not the white man’s concubine or his laundress, but rather the center of attention that she intentionally draws. She is aware of being a commodity, consumed by the GI, the street man, and the media; she is also a consumer herself, of commodities, modern thrill and pleasure, and the attention and prestige associated with the ride.

Figure 4.3 “Shanghai characters: Jeep girls,” 1946. Xing guang.

Figure 4.3Long description

Beneath the jacket, she wears a Qipao and lavish cosmetics. In the lower left corner, an undersized U.S. officer stands in front of a Jeep with his arms akimbo.

Figure 4.4 “A tribute to Jeep girls,” 1946. Zhilan huabao.

Figure 4.4Long description

The Jeep zooms quickly from left to right as the city passes by in the background.

Despite the prevalent conservative attacks, the Chinese Jeep girl discussion was once a vibrant intellectual debate over modernity and Westernization in which liberals, leftists, and feminists all participated. Hong Shen, an American-educated writer and professor, attributed the enmity toward Jeep girls to the sensitive nature of sexual relations and common phenomena of xenophobia, a universal “bias towards a foreign race” in the game of love.48 Dong Shijin, a Cornell University–educated agriculturist and educator, encouraged such interactions because “no other bonds are stronger than the marriage bond,” and asked why Chinese students or workers abroad could marry foreign women but Chinese women could not seek foreign husbands.49 Luo Jialun, a student leader during the May Fourth Movement and later president of Tsinghua University, called for abolishing the frivolous term “Jeep girls,” encouraging educated Chinese men and women to interact more with the Americans to help eliminate the current misunderstanding.50 Such a suggestion was reiterated in an article in West Wind, one of the most popular magazines of the time, which introduced in detail American dating culture as well as the idea of formulating a new “formal upper-class social intercourse” in China.51

These liberal voices are not included in existing studies of the Jeep girls or, at best, are regarded as pro-government propaganda. Indeed, as will be shown later in this chapter, Chinese officials did try to educate the populace about the American social custom of interacting with women along a similar line, aiming to promote harmonious diplomatic relations. But these defenders spoke out of conflicting ideological and political positions. While some, like Luo Jialun, were anti-Communist officials who might have had the government’s agenda on their mind, others, like Hong and Dong, were leftist intellectuals sympathetic to the Communist Party. What they shared was a defense of individual freedom and cultural cosmopolitanism, echoing the liberal avowal of modernity since the New Culture Movement.

Likewise, feminist critics were also divided on the issue. Some were critical of the corrupting effects of Western materialism on women, as Jeep girls’ “fat wallets are filled with American dollars, perfumes and powders, authentic chocolates and chewing gums brought by airplanes,” and all are “Westernized” and “forget about their black hair.”52 Others, in contrast, linked the Jeep girls with women’s liberation, highlighting the gender inequality and systemic oppression explicit in male critiques. For example, one author wrote in the influential leftist magazine Modern Women that Jeep girls were cursed by men out of jealousy, and women were blamed as the primary cause of national and racial extinction only because they were easy to bully. The real oppressor here, they argued, was not men in general, but fascism and feudalism.53 Another opined that Chinese women were always the ones to blame: “Our police did not try to catch the American soldier who rode a Jeep into a coal station causing a big mess, but everywhere looking for the Jeep girl.”54 These feminist commentators shared the common agenda of gender equality. But their varying stances further underlined the ambiguity of the Jeep girls as symbols, as well as the difficulty of choosing sides when it came to these deeply entangled issues of Jeep girls, American soldiers, Western-style modernity, and women’s liberation.

“I Am a Jeep Girl”

One might expect complete silence from members of such a marginalized and stigmatized group. But Jeep girls, either so labeled or self-claimed, did speak out, both in words and in action. In 1945, outraged female students from a missionary college in Chengdu smashed a newspaper office that had published a pornographic poem mocking them.55 In postwar China, some women “instigated GIs to insult Chinese policemen” who were questioning them.56 More often, women wrote open letters to journals defending themselves in the name of economic necessity or patriotic service to the nation.57 One college student explained that the majority of her roommates worked as dance hostesses for GIs at night because they needed additional income to pay off loans.58 Another student attributed working as a Jeep girl to the sacred cause of serving the nation after her family had rejected her plan to join the army.59 These voices reflect both the harsh material reality of dislocated students during and after the war and some women’s ability to co-opt the official Nationalist agenda for their own narratives. Toward the end of the war, Chiang Kai-shek launched a major recruitment campaign, soliciting college students’ direct participation in the war effort. While few would see working-class women’s hostessing as a sacrifice for the nation, educated women’s wartime service using their bodies remained controversial for China’s patriarchal nation-building project.60

An analysis of two self-identified Jeep girls’ accounts may afford us insights into the experiences and thoughts of women who forged connections with American soldiers on various levels.61 In 1948, West Wind published a letter from a university student named Lu Xi, asking whether a Chinese woman could and should marry an American man. She told the story of how she met an American officer on her way home and soon developed a close friendship with him. Afterward, she noticed a drastic change in the attitudes of her male schoolmates toward her: Admiration became finger pointing, with some calling her a Jeep girl. Though her anguish and plight were unsurprising, her candid self-portrait was nonetheless illuminating:

I am a twenty-one-year-old sophomore in college. I know my body is strong and pretty, not the Lin Daiyu type of frail beauty. I have an outgoing and carefree manner, earning me many male admirers at school. … I do not really like flamboyant clothing. But my clothes are fitting. I keep them tidy and elegant because I do not like to wear flowery clothes to show off. Meanwhile, I do not want to wear non-fitting clothes to cover up my shapely body either. In middle school, I enjoyed sports and music. My body was thus fully grown and spirit pleasantly developed. I have never restrained my breasts, nor do I like to use yellow cream to enhance leg skin color. I let nature take its course in everything. I am quite tall, neither fat nor skinny.62

Lu Xi spent the entire first page of her four-page essay describing her own body. She emphasized her natural and healthy beauty, distinguishing herself from both traditional Chinese frail femininity, represented by the iconic character of Lin Daiyu from Dream of the Red Chamber, and the highly commercialized modern women’s style fashioned by Western cosmetics, makeup, and other commodities. Almost unabashedly flaunting her unbound breasts, shapely physique, and love for sports, she celebrated a body free from both Chinese traditions and Western accessories. This image illustrated a type of ideal modern Chinese woman, healthy and fit, educated and civilized. She was neither traditional Chinese nor superficial Western, but a “real” modern woman.

The idea of a liberated woman’s body aligned well with the May Fourth message of freedom and equality. The modern woman’s “robust beauty” (jianmei) was also promoted by reformist intellectuals and the Nationalist Government through new physical education curricula and mass sports programs.63 However, Lu Xi’s emancipation remained limited. Having acknowledged strong mutual feelings between her and the GI, she insisted that she had kept her “dignity and only allowed hand holding once but no kisses.” Neither did she have the courage to confess to her Confucian father about her American boyfriend. Her initial protest that “I do not accept that I belong to any type of Jeep girl” was eventually undermined by the self-questioning that ended the letter: “Am I a Jeep girl?” This question resonated with the dilemma faced by Chinese women in forging a type of “moderate Chinese modernity” between “American depravity (glamorous and oh-so-romantic) and the dull prison of Confucian morality.”64 Despite her declaration of possessing a modern body, Lu Xi remained unsure of the subjective position of a Jeep girl.

Unlike Lu Xi, beset by anxiety and hesitancy, Shen Lusha identified herself as a Jeep girl and openly discussed her “desire to be possessed” by her lover, Harry. An English speaker brought up in a middle-class family, she presented herself as the lonely wife of a Nationalist army officer stationed in India and claimed to have met the American pilot through a female friend who was once a dance hostess. In her account, Harry’s “greatness” included both his “body and soul” and the wealth of his material goods, including his rations of chocolate, gum, coffee, and milk, as well as American perfume, lip balm, nylon stockings, and Airstep leather shoes. Lusha was quite frank about the convenience and benefit of her using and sometimes selling these goods in the lucrative black market, while declaring her dislike of those women who focused only on money. Having an extramarital affair with a foreign man while her husband was serving the nation abroad certainly made her an easy target. As she put it, she had already paid the price of being ostracized by her family and social circles, and she was even stalked and reported on by local tabloids. But in the end she decided, “My behavior is my own business.” Knowing that Harry would be returning to America soon, “all I need is to enjoy my lover even for a month.”65

Playing on the Chinese variant of carpe diem, Lusha’s insistence on enjoying Harry while the affair lasted should be read as intentionally provocative. Her piece was a direct response to an earlier article published in the same journal that ridiculed Jeep girls’ attraction to GIs’ exotic physical features and material wealth.66 The journal’s intention in publishing her piece was also suspicious. In the accompanying illustration, she was dubbed “Eve of Chongqing,” with an unmistakable biblical connotation of seduction, corruption, and danger. Like most pictorial representations of Jeep girls, Eve of Chongqing sported curly hair, full lips, large eyes, a long nose, and a curvy body against a backdrop of department stores, movie theaters, dance halls, and restaurants. Her completely Westernized features, combined with a hedonistic lifestyle and philosophy, moral and sexual decadence, and unrepentant attitude, were supposed to trigger immediate aversion, fear, or discomfort, to say the least. But apparently not all readers felt this way. One female reader responded with praise for “Mrs. Lusha’s courage and frankness” in “wanting and daring to love” as “a modern figure”; this reader asked the rhetorical question, “who would not hope for sexual and spiritual satisfaction?”67

In fact, in the accounts by these “Jeep girls,” American soldiers were often portrayed as boyish, brash, crude, and fresh, like “kindergarten kids,” while Chinese women were the sophisticated ones.68 Remembering her first GI friend who laughed loudly, flirted constantly, and kissed her goodbye without permission, a college student said, “I really don’t know what to do with these over-innocent country bumpkins.”69 These impressions might be informed by stereotypes that had long existed in Sino-US relations, metaphors such as China being the old civilization and the American nation like a young man. But their observations were not without merit: The majority of the soldiers they encountered had grown up in America’s working-class suburbs or rural areas and many were indifferently educated and parochial, whereas some of the Chinese women actually hailed from families of wealth and privilege and had been educated at prestigious English-language schools.70 Such a dynamic was not exclusive to China. Women across the globe described American soldiers in similar language, as being childish, impetuous, boastful, and flamboyant, prone to talk big, and fond of chasing after girls and spoiling them, making the GIs more attractive.71

Like the modern girls who emerged around the world in the interwar period, Chinese city girls had learned English, dance, and skating; consumed Hollywood movies, jazz music, stockings, and cigarettes; increasingly dressed according to the latest American fashions; and became conspicuously visible in public spaces.72 They now met the real Yanks in movie theaters, dance clubs, and roller-skating rinks and at other events hosted by the government, the US military, and organizations like the YMCA and YWCA. American dating was a foreign concept and an adventure, and American dollars and products made these war heroes even more appealing in a time of postwar material dearth.73 As in other regions around the world, in China, GIs were in demand for their sacrifice during the war, possession of material goods, and embodiment of the modern West. Meanwhile, such attractions also revealed prevailing racial and sexual perceptions and fantasies about American men. One woman described her GI dance partners as having “blue eyes, blond hair, and long nose,” like “animals liberated from the lonely desert,” “thirsty for new things.”74 Another said she was attracted to her lover’s red hair, thick eyebrows, straight tall nose, short beard, and handsome and strong body, better than any Chinese man, reminding her of a fictional medieval European knight or Douglas Fairbanks Jr. on the silver screen.75 Through popular magazines, movies, and real-life interactions, Chinese women encountered American men, whom many saw as more romantic, chivalrous, and attractive than their Chinese counterparts.

The limited voices from Jeep girls show a level of agency that has not been taken into account in previous studies of Sino-US encounters. These women fought conservative accusations, justified their relationships with foreign white men in the language of individual freedom and patriotism, and presented themselves as enlightened modern women. Some used their romantic encounters with GIs to explore social and sexual freedom, which was largely restricted by traditional moral codes or the new conservative gender norms of the Nanjing decade. Others defied Orientalist fantasies about Chinese women popularized in Hollywood movies, such as bound-feet concubines or sexualized dolls. And yet most did not want to be called Jeep girls and insisted these interactions were romantic rather than materially driven; many who had actual romantic relationships or even married GIs did so quietly. Thanks to the GI War Brides Act of 1945 and the War Fiancées Act of 1946, Chinese women were able to enter the United States in large numbers for the first time. However, most of the more than five thousand women admitted between 1945 and 1950 did not marry white soldiers. Instead, they reunited with Chinese American veterans, many of whom they had met or married long before the war.76 In November 1947, South China Morning Post reported an all-time record for new marriages in Hong Kong, as Chinese American ex-servicemen were in a hurry to tie the knot by the end of the year, believing the War Brides Act would soon come to an end.77 These veterans included both Chinese Americans who were born and raised in America and recent Chinese students who joined the US military while studying in the country. There were exceptions, including the high-profile marriage between Chen Xiangmei, also known as Anna Chennault, and General Claire Lee Chennault, the acclaimed leader of the “Flying Tigers” in China. Despite their elite status, their marriage was deemed illegal in the general’s home state of Louisiana. As a result, the general had his will probated in Washington, DC, instead, to ensure its legal recognition and validity.78

“China Doll” or “Chinese Rot”: GIs’ Views of Chinese Women

China Doll

World War II extended the size and reach of American power around the world, enabling its access to local women “ranging from marriage to prostitution, and a range of relations and interactions in between.”81 The rich corpus of studies on the American military has demonstrated the significant role of sex in reconfiguring the postwar power structure in both domestic and international contexts.82 Hierarchies of gender, race, and class informed attitudes, policies, and practices on both sides that can be traced to earlier imperial traditions and colonial institutions. Old patterns of cultural bias and racial discrimination continued to structure the asymmetrical power relations between America and other nations, whether defeated, newly independent, or Allied, and deeply shaped GIs’ daily interactions with local societies.83 These resemblances reveal the imperialist origins of the American empire, on the one hand, and the intimate links between military prostitution and sexual violence, on the other, which often transcend political agendas and military objectives. As Cynthia Enloe argues, such “militarized masculinity” enabled specific kinds of sexual encounters in the shadow of military presence, promoted the image of a hypermasculine soldier, and legitimized the military’s supportive attitudes toward prostitution and lack of disciplinary actions against sexual violence.84

Upon landing, most American soldiers had only a foggy idea of China. As former army officer William W. Lockwood recalled, back home, China meant “the end of the world,” “a lonely laundryman down the street, an occasional bowl of chow mein, a headline with unpronounceable names in the evening paper.”85 Army soldiers in the CBI Theater had been looking forward to girls in China long before stepping on the soil; prostitution in India was a routine recreation set up by the US military, which soldiers felt entitled to.86 For officer Elmo Zumwalt Jr., the initial experience of entering the city of Shanghai included “a bevy of young girls” who “threw themselves on the car shouting, ‘Hey Joe, Meg Wa (American) can do for free,’” being “a fitting tribute to the amorous generosity of the prewar U.S. sailor.”87 Marine veterans of the Pacific War were thrilled to learn of their new mission in China, rather than in Japan, because of their knowledge of the US Marine Corps’ historical ties and of what China missions usually entailed.88 If the leathernecks had supposedly “enjoyed a reputation with the Chinese” since the nineteenth century, according to General DeWitt Peck, China also had a positive reputation among them.89 Senior members passed down their wisdom about what the decadent East could offer, from affordable and easily available entertainment in cosmopolitan cities to hospitable locals and light military tasks. But they also gave timely warnings. “I knew that venereal disease hits the white man harder than it probably does anyone else,” said General William Worton, referring to various diseases that could not be cured by Western medicine, malaises conveniently dubbed “Chinese Rot” and “Chinese Crud.”90

Besides peer wisdom and popular knowledge, military publications were another major source of GI education. Special China guides repeatedly informed soldiers that the Chinese were “much more reserved,” especially in relationships: Except in a limited circle in Tianjin and Beijing, “You just don’t have dates, you don’t go to social dances, and parties with girls are few and far between.”91 The term “cultural differences” was often used to account for friction over sexual relations and became a convenient catch-all that trivialized conflicts, freeing GIs from any responsibility. In his memorandum to Chiang Kai-shek, General Wedemeyer, who commanded US forces in China from 1944 to 1946, attributed criticisms of GI misbehavior to different social customs and protested against the Chinese term “Jeep girls,” emphasizing Americans’ high respect for Chinese women.92 Meanwhile, in official guides, these “reserved” people were also said to be warm and attractive, like “the modern Chinese girl, in her long, closely fitting gown, her bare arms and short hair.”93 Military publications and popular media continued to perpetuate the image of hypersexualized Oriental women in erotic bodies, with racially and sexually charged stereotypes commonly plugged in official publications like North China Marine and Yanks.94 During WWII, American soldiers were seen as “red-blooded men” whose sex drive could only be channeled, not suppressed. The media promoted images of (over)sexualized women to motivate soldiers in their liberation missions, and “pinups” were developed to a new level. This hypermasculine culture within the military induced sexual promiscuity and aggression and profoundly changed its young white soldiers.95

Overall, when it came to Chinese women, the US armed forces had conflicting messages for its troops: They were both memorable “warmies” and dangerous carriers of diseases. Race informed how the military managed sexual relations with local women and affected how servicemen related to them. Since the nineteenth century, Asian women had been linked to the duality of lure and danger, such as the self-sacrificing Madame Butterfly and the devious Dragon Lady stereotypes. The ultimate embodiment of the Yellow Peril, they entrapped white men with sex and drugs, seducing them into a life of obscenity and violence and endangering the white race by giving birth to racially mixed children.96 The assorted racial stereotypes and sexual fantasies were best represented in the supporting characters that the likes of Anna May Wong played on the big screen in the 1920s and 1930s, images of women as exotic and erotic, cunning and cruel.97 Many politicians and even medical professionals in the late nineteenth century believed that Chinese immigrants carried distinct germs that would be transmitted to white men through Chinese prostitutes, leading to the Page Act of 1875, the first restrictive immigration law in the United States, which effectively prevented the entry of Chinese women.98 The subsequent Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers, was not repealed until 1943, when an annual quota of 105 was set for Chinese immigration. Until after WWII, most US states enforced a range of “anti-miscegenation” laws that prohibited intermarriage between individuals deemed white and those of other races, particularly black or Chinese. These laws began to be modified by postwar legislation such as the War Brides Act of 1945 or overturned at the state level, but were not invalidated at the federal level until the 1960s. Within these legal confines, Chinese brides faced persistent racial discrimination and continuing immigration restrictions in America.99

As the Chinese changed from inadmissible aliens to wartime allies after Pearl Harbor, a more positive China image emerged thanks to American propaganda. Chinese women now included modern, educated, English-speaking, and Christian women represented by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, as well as kind, hardworking, and resilient peasant women like those depicted in Pearl S. Buck’s novel The Good Earth.100 However, the seductive and dangerous Oriental woman by no means disappeared from the American psyche. Military guides advised a GI Joe to stay away from the traditional solaces of “wine and women,” for both were “loaded.”101 Through the prism of an ordinary American soldier, the army newspaper Stars and Stripes cautioned soldiers on the various Chinese women in the entertainment industries, such as “the bar girl known as Lou” who made the GI act “like a fool” and spend all his nine-month pay in one night at the bar.102 Even Madame Chiang, who conquered Congress with her Wellesley-educated eloquence, could not completely shed the shadow of the Dragon Lady.103 The mixed messages about Chinese women existed in parallel with the overall American view of China: a new and modern democratic nation as an ally, on the one hand, and a conservative and corrupt country requiring mentorship, guidance, and even occupation, on the other.

For marine veterans who saw civilization for the first time after years of hardship, “women came second,” only after fresh, non-GI food.104 Soon, some soldiers complained about the limited opportunities for dating due to China’s conservative social atmosphere. The first group of 221 army wives did not arrive in China until September 18, 1946, while the first group of marine wives arrived about two months earlier. Dependents made up approximately 10 percent and 20 percent of American navy and marine personnel throughout China in September 1947 and January 1948, respectively.105 Some officers dated white women, including expatriates from both Allied and enemy nations.106 Jewish officer Lou Glist, who was assigned to oversee the approval of marriages between GIs and foreigners, observed that American soldiers were highly sought after. He noted that some women in Shanghai were willing to pay GIs several thousand dollars for what they saw as a ticket to the “promised land,” leading to a phenomenon of “marriages of convenience” arranged “strictly for financial gain.”107 More commonly, however, China was “experiencing the exuberance of soldiers and sailor unleashed,” as the “dissipation of money, energy and sperm, accumulated over these many months away from home, has excited sellers of all sorts of merchandise.”108 American military pay was undoubtedly attractive in war-torn China, which was filled with refugees and prostitutes. During and after the war, commanding officers and soldiers openly frequented brothels and brought women back to the barracks.109 At the beginning of the occupation mission, General Worton requested that 1 million condoms be shipped.110 When one private reported he was “always unexposed,” his officer scoffed with a questioning, “I do not believe that. Aren’t you a man?”111 Decades later, one commander admitted in an interview that there was “all kinds of misbehavior” and “it was not America at its best.”112

In contrast with Japan and Korea, where the US military relied on regulated military prostitution, there was no separate system for GIs in China. In the middle of the civil war, a camp town structure as adopted by its Asian neighbors would certainly threaten the Nationalist regime’s claims of sovereignty, legitimacy, and new status as a world leader. Instead, US troops were located in the very center of Chinese cities and relied on existing systems of prostitution, sharing space and competing with local customers. As in Japan and Korea, the American military made halfhearted efforts to contain venereal disease. Prior to their arrival in China, marines had been shown educational videos about the dangers of venereal disease. To ensure soldiers’ health, the MPs labeled hotels, nightclubs, and dance halls “In-Bounds” and “Out-of-Bounds” and occasionally raided brothels and hotels. Some commanding officers asked soldiers to be inspected and take prophylactics upon their return after liberty.113 But in general, regulations over prostitution remained loose, and no punishments were enforced as long as exposures and infections were reported. The wonder drug penicillin provided a safety net for soldiers on the ground, and how they spent their liberty time was “one of complete tolerance.”114 Regarding local collaboration, the military took an inconsistent approach. On the one hand, it pressured the Chinese government to ban unauthorized brothels and control the rampant problem of venereal diseases among prostitutes. On the other hand, it requested local authorities’ cooperation to satisfy soldiers’ material, physical, and sexual needs, such as tax exemptions on restaurant and bar checks and the opening of special entertainment sites for servicemen, despite existing local bans or restrictions on cabarets and nightclubs.115

Officially, military publications like A Pocket Guide to China and A Marine’s Guide to North China were meant to prepare a young GI for his new mission in the foreign land. They instructed him to distinguish between “the average Chinese girl,” who “will be insulted if you touch her, or will take you more seriously than you probably want to be taken,” and “Chinese girls in cabarets and places of amusement who may be used to free and easy ways.”116 These nuggets of wisdom were confusing and impractical at best, if not misleading; their language mixed danger and attraction. In reality, the pronounced respect for Chinese women and harmonious relations often came to naught because of excessive consumption of alcohol, cultural arrogance, racial discrimination, and, ultimately, a toxic military culture that allowed or even enabled systemic tolerance. Americans’ long-term racism toward the Chinese had a powerful impact on GIs’ perceptions of their mission in the country and their attitudes toward the locals. American servicemen’s descriptions of Chinese women and China at large, from commanders to soldiers, showed not only a feeling of national superiority, but also an enduring colonial mentality.

The Peking Rape Incident and the End of Jeep Girls

I am a quintessential nationalist when it comes to sexual relations, and I cannot bear to see our beautiful female compatriots being trampled by foreign bastards … if I had tens of millions in gold, I would buy some white slaves for the enjoyment of Chinese rickshaw pullers, coolies, and menial workers!

The actual and imagined romance between Chinese women and American GIs coexisted with the harsh reality of sexual violence toward women from all walks of life. On November 1, 1945, two working-class girls in Shanghai narrowly escaped assault by two GIs and one sailor, who stabbed local policemen with knives. The assailants fled only after spotting a group of Chinese soldiers stationed nearby, “armed with pistols, rifles and Thompson sub-machine guns.” They happened to be members of the American-equipped New 6th Army, famed for their training and heroism in fighting the Japanese.118 On September 1, 1946, a civil servant’s wife in the capital of Nanjing was chased by GIs on her way home from a late show, where she was raped outdoors and sustained injuries.119 On August 1, 1947, a factory worker in Qingdao was gang-raped by four American servicemen and pushed down a hill after they had driven away her eleven-year-old son, who had been calling desperately for help.120 On August 7, 1948, an orchestrated gang rape took place at the end of a farewell dance party in Wuhan, perpetrated mostly by American merchants and officers.121

These seemingly isolated incidents show a familiar pattern: drunken soldiers on liberty seeking pleasure and behaving badly, followed by the American military’s disappointing legal maneuvers and inconsistent compensation policies. Even major American media acknowledged the severity of the problem and its impact on bilateral relations. On October 13, 1946, a New York Times correspondent reported a public statement by Zhang Dongsun, a renowned philosophy professor and leader of the liberal “third force.” Zhang condemned American servicemen for being guilty of “drunkenness, gambling, seeking women, smuggling, illegal sale of government properties, robbery, manhandling, killing through reckless driving, insulting and violating Chinese women.”122 Despite numerous official complaints and public warnings of this nature, the US military’s response was dismissive, with Lieutenant General Alvan C. Gillem calling them mere political propaganda. Also in October, Nathaniel Peffer, a veteran China journalist and then a professor at Columbia University, wrote a memo at the request of Ambassador Leighton Stuart. In it, he pointed out that “for the first time America begins to occupy a new role in Chinese thought, and it is a role that denotes a loss of moral prestige.”123 By the end of the year, when the American left-wing magazine Amerasia warned “GI Welcome Wears Out in China” and “American policy in China is transforming our soldiers into ambassadors of ill-will,” a new type of anti-American sentiment was fermenting, a portent that a serious incident was about to break.124

On Christmas Eve 1946, Peking University student Shen Chong was raped by an intoxicated Corporal William Gaither Pierson, assisted by Private Warren Pritchard. On her way to watch a Hollywood wartime romance, the nineteen-year-old encountered the two marines, who proceeded to “escort” her to a nearby freezing-cold open field in downtown Beijing and held her there for three hours until she was rescued by the patrolling Joint Office Sino-American Police. In the wake of the rape, accumulated Chinese anger exploded. On December 30, a large number of university students in Beijing joined a demonstration against the reported rape, and the protest quickly expanded nationwide to more than twenty-five cities (see Figure 4.5).125 Like the earlier incident involving the killing of rickshaw puller Zang Yaocheng, protesters demanded apologies from the American military, punishment of the perpetrators, and the complete withdrawal of US forces from China. A general court-martial held in Beijing found Pierson guilty of rape and sentenced him to fifteen years of confinement in January 1947. But the verdict was overturned by the Judge Advocate General of the US Navy in June, a recommendation approved by the Acting Secretary of the Navy in August. Pierson was exonerated, an outcome that led to further demonstrations.

Figure 4.5 Tsinghua University students protesting “American brutalities” in Beijing, January 1947. Lianhe huabao.

Ultimately, such legal injustice was enabled by the system of extraterritoriality that granted the United States exclusive military jurisdiction over its service members in China. Furthermore, American rape law at the time demanded that women’s physical struggles must be corroborated by medical evidence or witness testimonies, and proving rape was a burden that women had to carry.126 The court-martial in Beijing, though appearing transparent, objective, and fair, actually revealed deep-seated prejudices against the Chinese as well as pervasive suspicions of women in rape cases, both within the American military and the wider society.127 Before the trial, one marine officer expressed fear that if Shen received compensation, many “girls of loose morals” who associated with GIs would cry rape. During the trial, the defendant questioned Shen’s plan for filing claims for compensation. After the initial guilty verdict, many marines in China thought the sentence was unfair, as Pierson had had too much liquor and mistook Shen for a prostitute; he was only a political scapegoat.128 One GI captured the prevailing mentality: “We put our arms around the girls’ shoulders, thinking, as their attitude implied, that they were just friendly street girls,” until the girls’ crying brought a group of Chinese police and soldiers.129 Never did it occur to these marines that sexual violence was more than a mere verbal mix-up, an innocent cultural misunderstanding, or a simple “mistake” that could “cause a lot of trouble.”130 Military authorities had long maintained distrust of “ill-intentioned” foreign women trying to take advantage of innocent American boys abroad, seeing them as prostitutes, gold diggers, or alleged rape victims for American government compensation. Many commanders believed that sexual violence was unavoidable, and even General Wedemeyer seemed puzzled as to why this incident had caused such a big stir.131 Facing violence on the street and injustice in court, women like Shen Chong had little chance of winning. Her elite family background and educational status might have made her case a national headline in China.132 But they did not shield her from the trauma of sexual violence or the injustice of the American legal system, infused with racist biases and intricately linked to the military’s systemic tolerance of sexual promiscuity and misbehavior.

Despite the victimization of Chinese women, both the Nationalist and Communist Parties prioritized the student protests and political campaigns, disregarding women’s experience in their own hegemonic nationalist discourses. The Nationalist Government insisted that the Peking rape was merely an isolated event caused by a drunk low-ranking soldier, in sync with the usual rhetorical strategy of the American military. Further, Chiang Kai-shek called the student protests a result of “instigation by the evil Party” and instructed his officials to attack the Communists rather than address the underlying issues.133 This was a consistent approach from May 1945, when disturbances over “Jeep girls” in Chongqing were said to be “promoted by ‘enemies and traitors,’” with government propagandas accusing Japanese collaborators and Communists for spreading rumors to create Sino-US friction.134 In the ensuing months after the rape, the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Education handled diplomatic and student affairs with much trepidation, and both directly reported to Chiang and the Executive Yuan on their progress. Local officials, tasked with controlling demonstrations, resorted to closely monitoring student protesters, occasionally leading to arrests and injuries.135 Meanwhile, the Nationalist Government launched a propagandistic counter campaign portraying “Soviets’ atrocities” in Manchuria as much worse. Pro-government student groups openly confronted the protestors and accused Shen Chong of being a Communist agent.136 Ultimately, in the regime’s desire for harmonious Sino-US relations, there was no place for victims of sexual violence.

Since wartime, the Nationalist Government had faced a dilemma in dealing with such sexual matters: On the one hand, it called on women to practice informal diplomacy and be good hosts, while on the other hand, it persistently promoted a conservative gender ideology. Like the US military, it also tried unsuccessfully to downplay GI sexual misbehavior, framing it as a cultural problem or an isolated legal incident. During the 1945 crisis involving Jeep girls, for example, the mayor of Chongqing lectured the community on American values concerning freedom and public interactions of the two sexes.137 Anticipating social tensions with the arrival of new American forces after the war, the Nationalist Government distributed “Guiding Principles for Enhancing US-China Military-Civilian Relations” to local administrations. The pamphlet took pains to explain the cultural distinctions between the two countries, especially how the two genders interact, urging that locals “should not make a fuss about Americans dancing with Chinese women, a common practice for them, and the act should not be seen as promiscuous.”138 While China’s official ideology on gender relations remained conservative for decades, the desire to make US troops “feel at home” created an urgent need to educate its people on American customs, especially those connected to the sense of tactility. This also led to ambiguous and even contradictory policies. For instance, the Nationalist Government had attempted to control prostitution and even ban cabarets in the previous two decades, though inconsistently and ineffectively.139 During the war, general orders prohibited dancing, yet large dance parties were still organized for American troops, who also frequently held their own events.140 After the war, the government continued to shut down and limit commercial dance halls in newly liberated areas. But exceptions were made to accommodate American guests’ needs, with many establishments kept open or reserved exclusively for GIs, barring local entry. Hampered by such conflicting goals and legal restrictions in prosecuting American servicemen, the Nationalists tolerated GIs’ sexual promiscuity and denied or trivialized their sexual violence, an approach that eventually backfired. To many of its critics and supporters alike, the regime failed in its mission to protect women and defend the nation. As an ally that had helped win the war, the Chinese had high expectations for the American “liberators,” which were drastically different from those of their East Asian neighbors. They also had renewed hopes for their own government, which had been actively promoting the new image of China as one of the “Big Four” nations in the world.

In contrast, the Communists were determined to turn the case into nothing but a political matter of American imperialism, intensifying their propaganda campaign amidst the escalating civil war. Party leaders in Yan’an instructed local organs in Nationalist-controlled cities to actively participate in demonstrations and blamed the Chiang Kai-shek regime for encouraging the American military’s continued presence through “secret treaties.” The goal was to lead the mass movement in the direction of isolating America and Chiang and resisting American attempts to colonize China.141 Notably, the timing of the incident was perfect for the launch of a larger anti-American, anti-Chiang movement, part of Mao Zedong’s major strategy of “opening the Second Battlefield.” The rape occurred the day before the new constitution was formally passed in the National Assembly. Chiang had convened the Assembly in November 1946, but both the CCP and the Democratic League refused to participate, deeming it a facade rather than a genuine representation of coalition and democratization.142 While maximizing anti-American sentiments inflamed by the rape, the CCP called for the withdrawal of US troops, protested against American aid to the Nationalists during the ongoing civil war, and opposed American interference in China’s internal affairs. Not unlike the Nationalists, who used the case to fire at the enemy, the CCP also sought to leverage the situation for its own agenda and did not view the incident as a women’s issue.

To the surprise of many, including the Communists, the protest movement following the Peking rape attracted a wide range of support among urban residents, from outspoken leftist and liberal intellectuals to businessmen, government officials, and American professors in China who expressed sympathy or participated in the protest.143 The case caused nationwide uproar and received supporting letters from overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia and America. Popular grievances against GI misbehavior had been accumulating since wartime. But none of the other American “atrocities” led to the same level of public outcry as the Peking rape case, including the two aforementioned cases: the killing of rickshaw puller Zang Yaocheng in Shanghai and the gang rape of dance girls and middle-class wives in Wuhan.144 Effective Communist organization certainly contributed to the success of the Anti-Brutality movement. But more importantly, gendered nationalist sentiments brought together a variety of groups across geographical and ideological divides. Sex inflamed patriotic passions and provided an emotional bond to all, transforming a private matter into a national event overnight, while race and class provided the principal framing for viewing the incident.

University students, more than 80 percent of whom were male, largely cast Shen Chong as a “virtuous elite woman.” Replying to an American provocation that Chinese soldiers also committed rape, the students said bluntly, “They bothered only the peasants and did not molest intellectuals.”145 A Tsinghua University student denounced GIs as being armed with American dollars, emasculating Chinese officials, and corrupting urban women.146 Women’s groups actively participated in the movement, albeit following the overall male-dominated nationalist agenda. Female students’ organizations highlighted Shen’s special status as a “holy university student,” different from prostitutes who asked for it and housewives who, despite enduring multiple assaults, did “not have the strength to resist.”147 Newspaper commentators attributed American soldiers’ misbehavior to racial discrimination and “colonialist mentality.” Some questioned why a white person who raped a Chinese woman could walk free, while black rapists of white women in America faced the death penalty, noting that “Shen Chong was not black.”148 Others challenged the notion of “American justice,” asking whether the outcome would be the same if a man with “yellow face” had raped a white woman, and pointing out that the Chinese were not “slaves living in America’s black slums.”149 A long-standing Chinese racial discourse on barbaric “foreign devils” also found its way into the new rhetoric, calling them beastly “red-haired bandits,” and shouting, “Go home – American devils, beasts, and drunken soldiers!”150 Overall, critics directly juxtaposed the rape, a national shame, with China’s honor of being a victor of WWII.151 In these representations, in which Shen and China were violated by aggressive foreign soldiers, Chinese sovereignty was understood and defined in highly gendered terms shaped by prevailing hierarchies of class and race.

In its “Guiding Principles” concerning the social interactions of GIs with local women, the Nationalist Government advised its people not to “treat American servicemen with an ‘inferiority complex or discriminative mindset.’”152 This directive captured the mixed sentiments and somewhat paradoxical attitudes prevalent among the Chinese. On the one hand, Chinese officials and intellectuals were highly sensitive to and critical of American racism. Visitors from China almost never failed to report the prevalent racial issues in American society, especially discrimination against the Chinese. Similarly, Chinese coworkers of American military personnel in China frequently voiced resentment at being treated as inferiors. As one interpreter noted, even someone like him, who had always “worshipped American civilization,” was shocked by the racism displayed by GIs, including Chinese American soldiers who adopted the racist attitudes of white men and acted even worse.153 Another administrative staff member felt that American pity toward China – whether stemming from sympathy or mockery – was the most emotionally difficult attitude for him to endure as it showed how inferior his nation was.154

On the other hand, China had its own biases, and society at large was wary of GIs’ intimate relations with Chinese women. Street mobs attacked women seen in public with GIs, and many elite families forbade their daughters from dating or marrying foreigners. According to an American army officer, Chiang Kai-shek refused to allow black troops in postwar China because of “his fear of miscegenation,” believing “the white soldier already excited the Chinese enough.”155 An old China hand put it more bluntly: “The upper-class Chinese are racists,” calling themselves the “Central Kingdom,” and although “you will never hear it said,” they “feel that unlimited social contact between their women and us, for example, could lead eventually to a mixture of the races.”156 If the controversy surrounding Jeep girls merely simmered with these paradoxical attitudes, they converged and erupted with intense fever after the nineteen-year-old Peking University girl student was raped by a white soldier who ended up walking free.

Casting China as a victimized young elite woman was a powerful nationalist trope that enabled the Communists to successfully propagate their political message of American imperialism, muffling and eventually replacing earlier intellectual debates over modernity and Westernization. After the Peking rape incident, sexual relations with American soldiers ceased to be a heated topic for serious intellectual debate or social gossip, and instead became a political battleground in the civil war. There was little coverage of Jeep girls in popular periodicals or tabloids that had previously published editorials, readers’ letters, op-eds, and sensational news related to the topic. Earlier defenders of Jeep girls became silent or turned into outspoken critics of the American military. For example, Hong Shen, then a professor at Fudan University, publicly supported the protests and clashed with pro-government students.157 The Huang brothers, known for introducing Western culture and ideas to China through the popular journal West Wind, participated in the Anti-Brutality movement.158 This reflected the larger political atmosphere of the late 1940s, when many Western-educated intellectuals grew increasingly skeptical of American claims to justice and liberalism. If sexual romance with the Americans had already triggered the conservatives’ fear of white soldiers in China and attacks on Jeep girls, the lack of justice shook the liberals’ belief in the American system and certainly put them in a difficult position to defend Jeep girls. As one prominent legal scholar asked, how can America use liberalism to lead the world while not even trying to maintain basic legal justice?159 While Chinese intellectuals had been enticed by the American ideals of democracy, freedom, and self-determination for more than a century, some now felt betrayed by its realpolitik, such as assisting a corrupt government despite neutrality claims, prolonging the civil war and Chinese people’s suffering, and what Communists called the imperialist intervention into Chinese affairs.160 Amid this hypernationalist attitude toward sexual relations with American “beasts,” Chinese women could exist only as rape victims or prostitutes. There was little actual or symbolic space left for the modern Jeep girls, some of whom previously could speak for themselves, albeit in a limited way. Women’s sovereignty over their bodies was now displaced by exclusive claims of nationhood by elite men and the ascending Communist Party, which would soon take over the entire country and the destiny of Chinese womanhood.161

Shadow of Jeep Girls

On November 5, 1986, the US Navy returned to China for the first time in nearly four decades, docking for a week-long port call in Qingdao. As the navy band played “Happy Days Are Here Again,” one thousand sailor-ambassadors were issued a thirty-two-page booklet titled “A Sailor’s Liberty Guide to China.” The guide “admonished them not to pursue Chinese women or drink too much.” During interviews occasioned by this visit, an elderly local man reflected on past interactions, noting that some US sailors and marines had “left an extremely bad impression” after 1945. A younger shipyard worker, who was barely two years old when the last marines departed, also commented that the Americans back then “grabbed women and didn’t follow traffic signs.”162

Sexual dynamics, whether fraternization or violence, deeply shaped Chinese perceptions of the American military presence and formulations of anti-American narratives. Nationalism is a gendered discourse, entailing both gender power within a nation and gendering of different nations. Scholars have long shown the intimate connections between masculinity and nationalism and how the production of new national identities relies on gendered constructions.163 As WWII drew to a close, China’s revival included the reclaiming of both masculinity and sovereignty. Facing the American military, a hypermasculine institution, citizens projected their collective sexual, racial, and cultural anxieties onto the bodies of women as symbols of nationhood. Elite women, particularly university students, became a cultural fixture of desire and derision and a key arena of power contestations between genders, parties, and nations. Chinese women were divided between the Jeep girl, the fallen woman causing racial and cultural contamination, on the one hand, and the rape victim of a white soldier, the symbolic bearer of the violated nation, on the other. Such gendered nationalist discourses, however, rarely take into account women’s diverse experiences and their interests, but rather further subordinate them to masculine domination. As Enloe has pointed out, “nationalism typically has sprung from masculinized memory, masculinized humiliation and masculinized hope.”164 Conservatives and the Nationalist Government portrayed women as frugal and virtuous dependents as well as patriotic pawns for promoting harmonious Sino-US relations. Communists targeted American imperialism for its assistance to the Chiang Kai-shek regime and were equally hostile to the Jeep girls. As such, women remained voiceless, and their stories continued to be filtered through patriarchal nationalist agendas. They were victims of both the US military’s hypersexualized and racist culture and China’s domestic party politics.

As the American military occupation became bygone history in the People’s Republic of China, memories of Jeep girls and the Peking rape endured. In Lao She’s famous 1957 play Teahouse, American soldiers appeared as villains on the streets of postwar Beijing, together with Nationalist spies and local hooligans who wanted to corral all dance hostesses, prostitutes, waitresses, and Jeep girls to establish a grand syndicate to serve the Americans.165 During the Cultural Revolution, individuals were forced to play the roles of landlords, Jeep girls, reactionary politicians, and conspiracists in public struggle sessions, enduring humiliation and torture.166 Shen Chong, who had adopted a new name, identity, and path, was also abused by the Red Guards, ironically, because of her alleged fraternization with American soldiers.167 Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, who was in charge of creating new revolutionary arts, removed a scene from the propagandistic movie Sea Eagle (Hai ying). The scene depicted a People’s Liberation Army officer driving a Jeep with his wife, which Jiang criticized for depicting a “Jeep girl” style.168 Madame Mao denounced Jeep girls as prostitutes for foreigners and claimed she had once slapped someone who suggested she should become one.169 In Communist propaganda and literature, the Jeep girls remained stigmatized, and their portraits were deeply shaped by new political agendas in the Cold War era.

Whore or victim? The dichotomous portrayal of Chinese women reveals how their experiences were marginalized in hegemonic nationalist historiographies. In contemporary China, gendered nationalist discourse, deeply ingrained with racism, sexism, and classism, continues to play a prominent role in national and international politics. The trope of Jeep girls morphed into other forms as miscegenation fears persisted in the presence of foreign men, stoking national pride.170 Meanwhile, the prototype of the Chinese female victim continued to be invoked during periods of Sino-US tensions. Upon entering the Korean War, the Communist Party launched another successful propaganda campaign against American imperialists, featuring the Peking rape incident on the front pages of publications decrying the Americans’ “brutalities” and “beastly behavior” in China.171 Even recent publications highlight scenes of Chinese girls being chased by “monstrous Jeeps” among all the other unforgettable “victory experiences” of 1945.172 Accompanied by the menacing specter of the GI rapist, the shadow of the Jeep girls continues to loom large and unsettling.