Refine search

Actions for selected content:

9 results

3 - Social Chilling Effects

- from Part II - A New Understanding

-

- Book:

- Chilling Effects

- Published online:

- 20 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 20 November 2025, pp 41-48

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Style, Category and Legal Framework of Mediation

- from Part III - Legal Framework of Mediation in China

-

- Book:

- The Mediation System of China from an Interdisciplinary Perspective

- Published online:

- 23 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 November 2025, pp 93-138

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - To Put It Delicately

- from Part II - Understanding Cultural Norms and References

-

- Book:

- Lost in Automatic Translation

- Published online:

- 08 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 69-93

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Citizen, the Most Important Office in a Democracy

-

- Book:

- Educating for Democracy

- Published online:

- 20 April 2023

- Print publication:

- 27 April 2023, pp 13-19

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

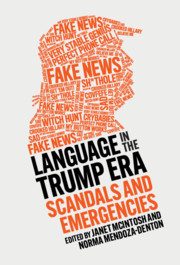

Language in the Trump Era

- Scandals and Emergencies

-

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020

Introduction: The Trump Era as a Linguistic Emergency

-

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 1-44

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Trump’s Comedic Gestures as Political Weapon

- from Part II - Performance and Falsehood

-

-

- Book:

- Language in the Trump Era

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 03 September 2020, pp 97-123

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 13 - Healing the Bonds of Affection

- from Part III - Deferred Dreams: Reflections on Politics and Society

-

- Book:

- Giving the Devil his Due

- Published online:

- 28 February 2020

- Print publication:

- 09 April 2020, pp 134-144

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - The Language Ideology of Silence and Silencing in Public Discourse

-

-

- Book:

- Qualitative Studies of Silence

- Published online:

- 30 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 18 July 2019, pp 165-185

-

- Chapter

- Export citation