Refine search

Actions for selected content:

99 results

Design Change of Projectile Points during the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene in the Pampas (Argentina)

-

- Journal:

- Latin American Antiquity , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 December 2025, pp. 1-21

-

- Article

- Export citation

Egalitarianism is not Equality: Moving from outcome to process in the study of human political organisation

-

- Journal:

- Behavioral and Brain Sciences / Accepted manuscript

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 November 2025, pp. 1-76

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Variation of Early and Middle Holocene Earth Oven Technology in Wyoming and Implications for Forager Adaptations

-

- Journal:

- American Antiquity , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 August 2025, pp. 1-20

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Combining Technology and Geometric Morphometrics: Expanding the Definition of the Garivaldinense in Southern Brazil

-

- Journal:

- Latin American Antiquity / Volume 36 / Issue 2 / June 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2025, pp. 360-380

- Print publication:

- June 2025

-

- Article

- Export citation

A 350 14C yr discrepancy between bone and tooth dates from the same grave at the Early Neolithic cemetery of Shamanka II, Lake Baikal, southern Siberia: reservoir effects or a misplaced mandible?

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 67 / Issue 5 / October 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 January 2025, pp. 939-951

- Print publication:

- October 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Hunting Pit Systems as Landscape Domestication: Large-Scale Hunting in the Arctic Regions of Sweden

-

- Journal:

- European Journal of Archaeology / Volume 28 / Issue 2 / May 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 December 2024, pp. 227-245

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Paiján obsidian points on the coastal desert of southern Peru and their source

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

11 - Lifespan and Mortality in Hunter-Gatherer and Other Subsistence Populations

-

-

- Book:

- The Biodemography of Ageing and Longevity

- Published online:

- 14 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 217-238

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Do counts of radiocarbon-dated archaeological sites reflect human population density? A preliminary empirical validation examining spatial variation across late Holocene California

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 66 / Issue 4 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 September 2024, pp. 610-623

- Print publication:

- August 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

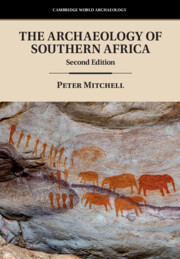

9 - Taking Stock: Herders and Hunter-Gatherers

-

- Book:

- The Archaeology of Southern Africa

- Published online:

- 15 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 231-271

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Archaeologies of the Pleistocene/Holocene Transition

-

- Book:

- The Archaeology of Southern Africa

- Published online:

- 15 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 160-188

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Hunting, Gathering, Intensifying: Forager Histories in the Holocene before 2000bp

-

- Book:

- The Archaeology of Southern Africa

- Published online:

- 15 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 189-230

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Hunter-Gatherers of the Late Pleistocene

-

- Book:

- The Archaeology of Southern Africa

- Published online:

- 15 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 125-159

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Archaeology of Southern Africa

-

- Published online:

- 15 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024

BONE POINTS IN TIME: DATING HUNTER-GATHERER BONE POINTS IN THE TERRITORY OF LITHUANIA

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 65 / Issue 5 / October 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 October 2023, pp. 1118-1138

- Print publication:

- October 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

2 - Pre-Prelude

- from Part I - Laying the Foundations for Global Society

-

- Book:

- Making Global Society

- Published online:

- 27 July 2023

- Print publication:

- 10 August 2023, pp 55-70

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Making Global Society

- A Study of Humankind Across Three Eras

-

- Published online:

- 27 July 2023

- Print publication:

- 10 August 2023

Procesos de manufactura e identificación taxonómica de pieles en Norpatagonia argentina (Parque Nacional Nahuel Huapi)

-

- Journal:

- Latin American Antiquity / Volume 35 / Issue 2 / June 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 June 2023, pp. 402-420

- Print publication:

- June 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

‘Come and Give my Child Wit’. Animal Remains, Artefacts, and Humans in Mesolithic and Neolithic Hunter-gatherer Graves of Northern Europe

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 89 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 June 2023, pp. 207-224

- Print publication:

- December 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation