Introduction

The Ica Valley on the south-central coast of Peru represents the known southern limit of the Paiján lithic complex (Bonavia & Chauchat Reference Bonavia and Chauchat1990; Chauchat et al. Reference Chauchat, Wing, Lacombe, Demars, Uceda and Deza2006). Known for their distinctive stemmed bifacial points, Paiján lithics are found along 1000km of the Peruvian coast and date from 13 000 to 9000 cal BP. Research on the Paiján complex has largely been confined to the north coast (Pelegrin & Chauchat Reference Pelegrin and Chauchat1993; Chauchat et al. Reference Chauchat, Wing, Lacombe, Demars, Uceda and Deza2006; Maggard & Dillehay Reference Maggard, Dillehay and Dillehay2011), but a probable site (14B-IV-45 and 14B-IV-46) has been identified in the Quebrada de Pozo Santo, in an oasis within the desert area between the Pisco and Ica valleys (Bonavia & Chauchat Reference Bonavia and Chauchat1990; Engel Reference Engel1991). The site, now known as Pampa Lechuza, was rediscovered in 2010 (Dulanto Reference Dulanto, Vega-Centeno and Dulanto2020); located at 180m above sea level (masl), it is midway between the middle Ica valley and the coast south of the Paracas Peninsula (Figure 1). Given its strategic position as a resting place between these two distinct and complementary ecological zones, systematic surveys and excavations were conducted at the site (Dulanto Reference Dulanto, Vega-Centeno and Dulanto2020).

Figure 1. Location of the Pampa Lechuza site and its relationship with the Quispisisa obsidian source. The 250km least-cost-path between source and find sites is indicated by the dashed line (figure by J. Dulanto & A. Icochea, base map: Google Earth Pro satellite).

Methods

The systematic survey conducted between January and June 2018 covered 30 800m2 and revealed several partially superimposed concentrations of lithics, shells and occasional ceramics. The area was divided into 20 × 20m quadrants for survey and collection (Figure 2); 68 quadrants were classified as low density and nine as high density. Low-density quadrants were surveyed by 2m-wide transects, and materials were collected individually. A Trimble M3 total station was used to record artefact locations (<10mm error). High-density quadrants were surveyed by 0.5 × 0.5m squares, and materials were collected in bulk from each square.

Figure 2. Mapping 20 × 20m quadrants for systematic surveys and collection, with the spatial distribution of the obsidian points (P) highlighted (figure by J. Dulanto & A. Icochea).

Results and discussion

More than 170 000 lithics and 59 ceramic sherds were collected during the survey. The lithic assemblage is predominantly composed of debitage, accounting for more than 162 000 items. The assemblage also includes over 4000 tools and more than 4000 other types of artefact and non-local raw materials; 513 artefacts have been identified as points in various stages of manufacture.

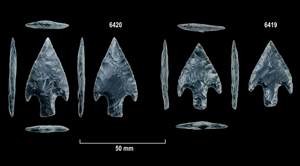

Diagnostic Paiján lithics include stemmed bifacial points, bifacial foliate pieces, unifaces and other tools on flakes, blocks, pebbles and cobbles. Among the 513 bifacial points, seven were made of obsidian. Five are fragmentary (distal tips and small retouch or resharpening flakes) and were found towards the north of the site; two more complete points (6419 & 6420) were found towards the south (Figures 2 & 3). Generally, the fragments exhibit the same colouration as the points, although three are more transparent.

Figure 3. Lithic artefacts from the Paiján complex found at Pampa Lechuza: obsidian Paiján points (6420, 6419, previously illustrated in Dulanto Reference Dulanto, Vega-Centeno and Dulanto2020: 251); fragments of obsidian bifacial points (II160A, 3936, II115D, I214C, 22118); other specimens made from materials other than obsidian (IV19A, 27985, 7044, 10294, II243B) (figure by A. Pérez-Balarezo).

Portable x-ray fluorescence (PXRF) analysis was conducted using a Bruker Tracer 5i Handheld XRF Spectrometer by Laboratorio de Arqueología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Results indicate that the obsidian used in all seven points is from the Quispisisa source (Figure 4), located on Cerro Jichqa Parco, Sacsamarca, Ayacucho (Burger & Glascock Reference Burger and Glascock2000). The source sits at 4000masl, 250km from Pampa Lechuza walking to the east (Figure 1). Previous evidence for the exploitation and transport of Quispisisa obsidian during the Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene has been limited to the highlands, although it is found up to 200 linear km from its source (Burger & Asaro Reference Burger and Asaro1978). Pampa Lechuza, at 180 linear km distance, is within this radius. This finding is also consistent with the use of obsidian from highland Alca (Cotahuasi, Arequipa) at the coastal site of Quebrada de Jaguay (150 linear km), during these same early periods (Sandweiss et al. Reference Sandweiss1998).

Figure 4. PXRF results for rubidium (Rb) and strontium (Sr), 90% confidence ellipses for all Peruvian obsidian sources also shown (after Rademaker et al. Reference Rademaker, Glascock, Reid, Zuñiga and Bromley2022, except for Puzolana which was collected and analysed by the authors) (figure by J. Dulanto & A. Pérez-Balarezo).

Artefacts 6419 and 6420 represent the first documented Paiján points made of obsidian in Peru. Both are complete, except for a minor stem fracture on 6419, are made from a dark-grey obsidian and show typical aeolian abrasion. Artefact 6420 shows a bi-convex blade and trifacial stem, measures 47.42 × 26.30 × 4.85mm and weighs 4.53g (Figure 5A & C). Artefact 6419 shows a rhomboidal blade section, measures 39.86 × 26.72 × 4.98mm and weighs 3.2g (Figure 5B & D).

Figure 5. Metric and technological analysis of obsidian Paiján points from Pampa Lechuza. (A, B) Standard photographs. (C, D) Position of measurements: TL, total length; BL, blade length; SL, stem length; SA, symmetry axis; MW, maximum width; BSW, blade/stem intersection width; SMW, stem maximum width; BMT, blade maximum thickness; BST, blade/stem intersection thickness; MT, maximum thickness. (E, F) Diacritical schemes with indication of removals patterns and partial knapping chronology (figure by A. Pérez-Balarezo).

Both artefacts have been shaped from flakes and follow a similar production process, which involved a flaking phase, at least four shaping phases (through soft-hammer percussion) and a final retouching phase (mainly through pressure technique) to achieve the desired outline (Figure 5E & F). These technological features match those previously described for Paiján points from northern Peru (Pelegrin & Chauchat Reference Pelegrin and Chauchat1993). Artefacts 6419 and 6420 also share morphological traits with Paiján points from Pampa de los Fósiles and Ascope, notably at Sites 13, 27 and 5 (Chauchat et al. Reference Chauchat, Wing, Lacombe, Demars, Uceda and Deza2006: 159, 306, 332, figs. 51, 133, 140).

The seven points are part of a larger sample of 682 specimens of Quispisisa obsidian found on the surface of Pampa Lechuza—almost all of which are debitage primarily representing the late stages of the chaîne opératoire. Obsidian artefacts seem to have arrived at Pampa Lechuza as finished or nearly finished products. This suggests that obsidian provisioning from Quispisisa involved not only significant mobility from and/or to the source, but probably also coast-highland intergroup social networks.

Conclusions

Before 2018, Paiján occupation of the south-central Peruvian coastal desert was unconfirmed. The 2018 survey and excavations, and subsequent technological analyses, confirm the Paiján affiliation of the Pampa Lechuza site, and provide evidence of Quispisisa obsidian use by early coastal hunter-gatherers—possibly as early as the Final Pleistocene–Early Holocene. Ongoing technological and sourcing research of these specimens will provide further insights into the mechanisms of exploitation, transport, exchange and use of obsidian on the south coast of Peru during this period.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the ‘Proyecto de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Paracas’ and the Sorbonne Université Emergence Project ‘La tropicalité, un mode d’émergence et d'innovations culturelles’.

Funding statement

This research was possible thanks to a research grant from the Dirección de Gestión de la Investigación, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.