Refine search

Actions for selected content:

11 results

Chapter 40 - Shelley and Popular Culture

- from Part IV - Afterlives

-

-

- Book:

- Percy Shelley in Context

- Published online:

- 17 April 2025

- Print publication:

- 24 April 2025, pp 309-316

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 16 - Visual Culture

- from Part IV - Afterlives

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to <i>Gulliver's Travels</i>

- Published online:

- 05 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 October 2023, pp 206-223

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Comics and Graphic Novels

- from Part I - Forms

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Comics

- Published online:

- 17 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 31 August 2023, pp 63-81

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

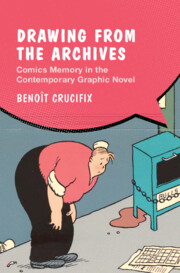

Drawing from the Archives

- Comics Memory in the Contemporary Graphic Novel

-

- Published online:

- 06 July 2023

- Print publication:

- 20 July 2023

Chapter 26 - Drawing Chicago: Chris Ware’s Graphic City

- from Part V - Traditions and Futures: Contemporary Chicago Literatures

-

-

- Book:

- Chicago

- Published online:

- 02 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp 370-386

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - Nineteen Eighty-Four and Comics

- from Part IV - Media

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to <I>Nineteen Eighty-Four</I>

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 01 October 2020, pp 232-246

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Graphic Novel Histories: Women’s Organized Resistance to Slum Clearance in Crossroads, South Africa, 1975–2015

-

- Journal:

- African Studies Review / Volume 59 / Issue 1 / April 2016

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 April 2016, pp. 199-214

-

- Article

- Export citation

266 - Comic Books and Manga

- from Part XXVII - Shakespeare and the Visual Arts

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 1899-1906

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part XXVII - Shakespeare and the Visual Arts

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 1861-1906

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

243 - Shakespeare and Children’s Literature

- from Part XXIV - Shakespeare and the Book

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 1720-1724

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part XXIV - Shakespeare and the Book

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 1661-1728

-

- Chapter

- Export citation