Christian Nationalism has been an increasing focus of scholars as it has come to dominate much of the Republican party and its voters (Gorski Reference Gorski, Jason and Jeffrey2019; Gorski and Perry Reference Gorski and Perry2022; Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs Reference Perry, Whitehead and Grubbs2022b; Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023). Existing research, however, has focused almost exclusively on individual attitudes and on how voters’ orientation to Christian Nationalism impacts attitudes on race, immigration, social policy, and even democracy itself (Armaly, Buckley, and Enders Reference Armaly, Buckley and Enders2022; Davis Reference Davis2018). This focus is important for understanding public opinion and election research, but it neglects the wider impact of Christian Nationalist ideas on public policy and the institutional change that often follows policy change.

In this article, I examine a key piece of the Christian Nationalist agenda, policy change at the state level seeking to change individuals’ perception of the religious foundations of the United States through symbolic legislation. I focus on Project Blitz, a legislative organization designed, like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), to create model bills for state legislators to introduce all over the country. What explains the success of Project Blitz in introducing these bills? Is it Republican state politics and the rise of support for President Trump? Or is it the traditional strength of Christian Right influence in states that has set the stage for Christian Nationalist policy? Focusing on this state-level manifestation of Christian Nationalist policy goals helps to evaluate Christian Nationalist behavior beyond attitudes and links it to the institutions and structures of the Christian Right movement from which it springs. The Christian Right has long been at work in the states (Green, Guth, and Wilcox Reference Green, Guth, Wilcox, Costain and McFarland1998; Rozell and Wilcox Reference Rozell and Wilcox2017; Green, Rozell, and Wilcox Reference Green, Rozell and Wilcox2003; Persinos Reference Persinos1994), taking advantage of the US’s federal system to enact policies in a piecemeal fashion.

Christian Nationalism is variously defined as a set of beliefs that identify the United States as a specifically Christian nation (Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020), that “idealizes and advocates the fusion of American civic life with a particularly ethnicized and exclusivist strain of Christianity,” (Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs Reference Perry, Whitehead and Grubbs2022a, p8), and an ideology that “sets out markers for who is rightfully American” (Lewis Reference Lewis2021). At its core, Christian Nationalism is a “pervasive set of beliefs and ideals that merge American and Christian group memberships” (Armaly, Buckley, and Enders Reference Armaly, Buckley and Enders2022). In recent scholarly literature, this concept has been largely approached as an attitudinal phenomenon, impacting voters and elites alike and driving their opinions on a variety of social, cultural, and political issues (Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020; N. Davis Reference Davis2023; Perry, Whitehead, and Davis Reference Perry, Whitehead and Davis2019). Frequently assessed as individuals’ responses to a battery of questions about their views on the relationship between the federal government and Christian theology and symbolism, the CN index has come under scrutiny by scholars who point out that the underlying assumptions of the CN scale are methodologically problematic (N. Davis Reference Davis2023), conflate versions of religion and conservatism (Smith and Adler Reference Smith and Adler2022), and do not account for the political and partisan context in which these attitudes are expressed (Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023). These critiques do not discredit the underlying reality of Christian Nationalist sentiment and motivation, but they do demonstrate the need to look further than a set of individual attitude measures to understand the multi-faceted phenomenon of Christian Nationalism.

Inexperienced observers might reasonably assume that Christian Nationalism is a new phenomenon, birthed by the election of Donald Trump and the social dislocation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Conversely, many scholars use the terms Christian Right and Christian Nationalists interchangeably (Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020; Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs Reference Perry, Whitehead and Grubbs2022b), assuming a simple name change for an old phenomenon. Neither of these approaches is precisely true. The inclination toward the attitudes we call Christian Nationalism has certainly existed in the Evangelical movement since the early 20th century (Gorski Reference Gorski2020; Noll Reference Noll1992; Marsden Reference Marsden2006). And scholars have explained the organizational actors and institutional impacts of Christian Nationalism by focusing on connections to the Christian Right and other social movements (Gorski Reference Gorski2020), organizational coalitions (Stewart Reference Stewart2020), and Republican Party politics (Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023). The Christian Nationalist impulse and some of the activities it motivates certainly link to the Christian Right movement of the last half century, but these are not synonymous.

The Christian Right movement of two decades ago was solidly wedded to incremental change within existing political institutions, particularly the Republican Party (Lewis Reference Lewis and Lewis2019; Conger Reference Conger2009). Many of the core organizations and leaders of the old movement remain active and retain their insider status and focus on Republican politics. However, many have seemingly abandoned the moderate messaging “that the Religious Right relied on for decades in order to present their policy program as compatible with pluralistic democracy” (Braunstein and Lawton Reference Braunstein and Lawton2019). Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey (Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023) add more insight into this movement and message evolution, empirically demonstrating the role that threat and need for dominance play both in Christian Nationalist ideologies and activism. “Christian nationalist political ends are that much more extreme when combined with an obsession with dominance and fear of loss” (p43). The rhetoric of threat specifically linked to policy and societal changes like legalization of same-sex marriage, prevalence of gender fluidity, and focus on social justice have motivated a sense of religious and political persecution that has yielded significant political participation gains for Christian Nationalism over the last 5 years (p36) particularly among people who were once solidly in the center of the Christian Right’s gradualist majority. So, while Christian Nationalism is not a new concept in the realm of religious right mobilization, the intensity and prominence of these ideas among politically activated Evangelicals is an evolution from the social movement scholars have long studied.

What does this mean for the Christian Nationalist activists at work to operationalize and mobilize CN attitudes into policy change? It means that instead of starting from scratch, they have a wide range of organizations, networks, and relationships to draw upon, and they have a history of cooperation and even fusion between Evangelicals and Republicans to build upon. This suggests that scholars should look beyond the attitudes of Christian Nationalism to the capacity and policy goals of the organizations these attitudes motivate. Christian Nationalist’s intensification of threat and evolution in messaging retain the insider strategy and organizational strength that was a hallmark of the Christian Right of the past. In this paper, I expect to find that Christian Nationalist policy change finds a better audience and more traction in contexts where the Christian Right has historically been strong. Not just in terms of proportion of Evangelicals and their Republican votes, but also in terms of organizational capacity, influence, and the existing ability of conservative Evangelicals to transform their policy preferences into actual proposals and introduction of bills.

Christian Nationalist policy change—Project Blitz

Christian Nationalism is often linked to voter attitudes (Whitehead, Perry, and Baker, Joseph O. Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018; Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020), but the connection between attitudes and behavior is not always a straight line. Christian Nationalism can also be linked to public protest and even political violence by its supporters (P. S. Gorski and Perry Reference Gorski and Perry2022). But voting and protest are, at best, indirect indications of influence on practical politics, which Christian Nationalists clearly desire. One concrete way to discern influence is to examine the legislation introduced that reflects the policy goals of a social movement. The ability to convince legislators to introduce bills demonstrates a movement’s cohesion, its ability to articulate its policy goals into actionable demands, and long-term nature of its commitment to the policy space (Holyoke Reference Holyoke2003; Nownes Reference Nownes2004; Gray and Lowery Reference Gray and Lowery1995). Legislators’ receptivity to social movements’ attempts to influence bill proposals also demonstrates a movement’s wider appeal to the public. If a legislator knows that their constituents support or at least align with a movement, they are much more likely to be receptive to requests for bill sponsorship and introduction.

Project Blitz was created by the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation, Wallbuilders, and the National Legal Foundation, all long-standing actors on the edges of the Christian Right movement. Project Blitz is “the playbook for a nationwide assault on state legislature in all fifty states,” (Stewart Reference Stewart2020, p153) and focuses on “religious freedom” legislation. It is an organization that seeks to change people’s perception of democracy and the United States with symbolic legislation tied to Judeo-Christian values and the religious foundation of American democracy. Project Blitz lays out model legislation with persuasive talking points for supporters, covering the topic areas of “Legislation Regarding Our Country’s Religious Heritage, Resolutions and Proclamations Recognizing the Importance of Religious History and Freedom, Public Policy Resolutions for Religious Liberty Protection, and Religious Liberty Protection for Professionals and Individuals, Teachers and Students” (Project Blitz Reference Blitz2020). These proposals clearly focus attention on the idea of America as an explicitly Christian nation based in a revisionist version of American History (Wallbuilders), an expectation that “action will cause America’s public policy and legal system to support and facilitate God’s purpose” (National Legal Foundation Website), and support for “legislators who promote policies that uphold and advance America’s dynamic Christian legacy” (Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation Website).

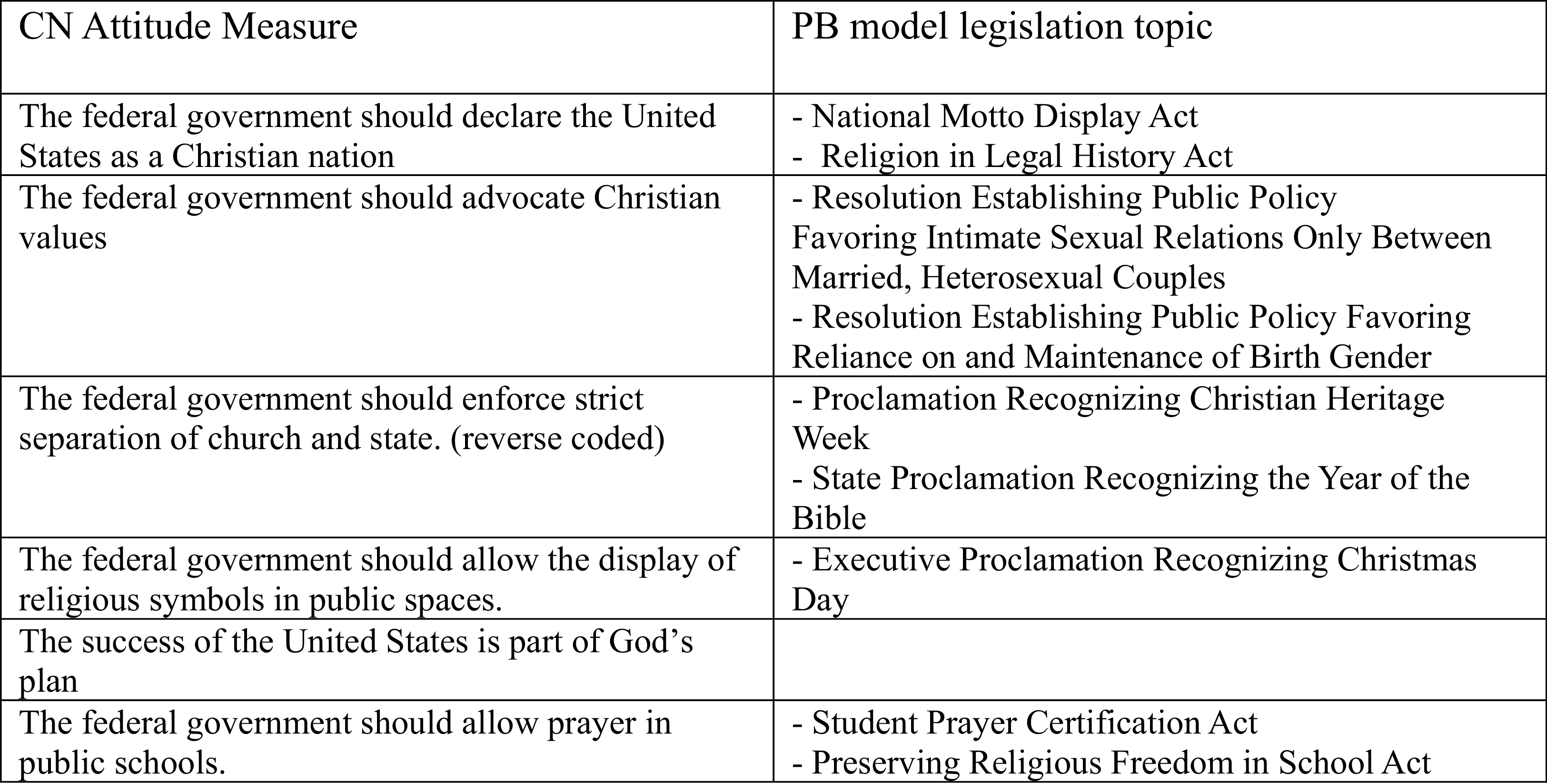

While the leaders of Project Blitz would not specifically characterize it as Christian Nationalist in orientation, scholarly observers have pointed out that the organization is trying to align law and public policy with conservative Christian beliefs about society, education, relationships, and personal freedom. “They contend that the state has a ‘compelling’ health and safety interest in promoting heterosexual relations, maintenance of birth gender, and adoption by married heterosexuals. And the authors make their … intent quite clear: to ‘define public policies of the state in favor of biblical values concerning marriage and sexuality’” (Brockman in Clarkson Reference Clarkson2018). We can also link Project Blitz’s model legislation to the most popular survey questions used by Christian Nationalism scholars to identify the attitudes associated with the ideology (N. Davis Reference Davis2023), demonstrating the connection of PB legislation to the CN movement. Figure 1 demonstrates these substantive connections between Project Blitz proposed legislation and the concepts scholars have used to identify Christian Nationalist attitudes.

Figure 1. Comparison of Christian Nationalism index attitude measures and Project Blitz model legislation topics.

Sources: (N. T. Davis Reference Davis2023) and (Project Blitz Reference Blitz2020)

While observers might dispute the specific links between individual CN attitude measures and individual model legislation, the bulk of the evidence of the topics and concerns of the PB model legislation links it to the CN attitudes discussed in the wider scholarly literature. Project Blitz is clearly focused on implementing Christian Nationalist policies in US states.

Project Blitz has explicitly adopted the model of American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) in its attempts to pass Christian Nationalist legislation in the states (Clarkson Reference Clarkson2018). The ALEC is an example of movement policy preferences transforming into a network of activists convincing legislators around the country to introduce state-level legislation that conforms to their free-market and anti-regulation preferences. ALEC exploits both the popular support for conservative policies and the lack of time and expertise that most state legislators have in policy development and bill writing (Squire Reference Squire1997, Reference Squire2007). Legislators whose constituents are primarily conservative Republicans find an easy avenue to satisfy their base by introducing model legislation produced by ALEC. The increase in Voter ID laws across the country over the last decade is an excellent example of this network model of social movement policy (The League of Women Voters 2021).

Most state legislatures are distinctly amateur in nature, with limited salaries and legislative aid, and time-limited sessions. Previous research demonstrates that legislators are much more likely to rely on interest groups for bill drafting under these conditions (Squire Reference Squire1997, Reference Squire2007). Organizations like ALEC and Project Blitz take this one step further with significant policy training and legislative analysis designed to help legislators not only introduce bills that align with the groups’ policy preferences but also to craft strategy and incentives for passage.

Having demonstrated that Project Blitz’s policy goals and initiatives closely align with the scholarly definition of Christian Nationalist attitudes, and noted the role that advocacy organizations like Project Blitz can play in resource-challenged state legislatures, I turn to a more detailed exploration of what explains the variation in the number of PB bills introduced in state legislatures. Legislation is one of the most concrete ways to measure a group’s influence in the politics of a state, and I expect to find that PB benefits from existing Christian Right strength and its attendant social movement infrastructure in attempts to enact symbolic Christian Nationalist legislation.

Data and methods

To measure the number of Project Blitz bills introduced in state legislatures, I am using data collected by BlitzWatch, a project encompassing organizations like Americans United for Separation of Church and State, Political Research Associates, Interfaith Alliance, and the Freedom from Religion Foundation (https://www.blitzwatch.org/). BlitzWatch has been tracking the introduction of Project Blitz bills since 2017; the raw data was provided to me by the primary investigators at Political Research Associates (https://politicalresearch.org). These are count data for each state for each year for both the introduction of bills and the passage of laws that can be linked to Project Blitz’s legislation handbook and its core policy goals. I have chosen to use the total number of bills introduced in 2019-2021 in order to account for growing impact over time, the vagaries of state legislative sessions (some meet only once every two years), and increasing empowerment of conservative Republican legislators through the Trump administration.

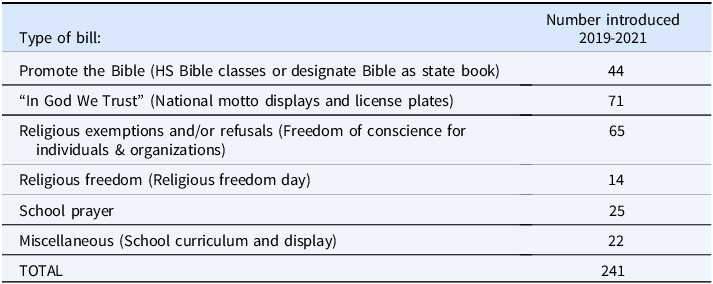

While Table 2 reports the number of Project Blitz bills introduced in each state in 2019-2021 (see below), Table 1 demonstrates the types of bills introduced. The specific language of each bill differs, so I use BlitzWatch’s categorizations to demonstrate the variety of bills introduced. Bills requiring or allowing the National Motto, “In God We Trust,” to be displayed in public buildings and/or schools, or providing for license plates with the motto, make up the largest number of introduced bills, with 71 bills. Bills allowing for religious exemptions or the right of religiously motivated refusal are the next largest category, with 65 bills. These bills cover “freedom of conscience” situations where individuals or organizations want to bypass existing laws and regulations for religious reasons (adoption agencies refusing to work with same-sex couples, pharmacists refusing to dispense birth control, business owners refusing to serve LGBTQ persons). Overall, 241 Project Blitz-motivated bills were introduced into state legislatures in 2019-2021.

Figure 2 reports a heat map for the number of PB bills introduced in each state’s legislature in 2019-2021. While Texas had the highest number of introductions, and 16 states had no PB bills introduced, the overall average number of bills introduced per state was 4.82. Given the variance (0-23 bills), however, the more telling descriptive statistic is that for states where any PB bill was introduced, the average number of bills was 7.01 (median: 6 bills). This suggests that in many states, Project Blitz bills were introduced as a group. These were not one-off attempts by legislators interested in teaching Biblical literature in high schools or providing license plates with the national motto. These were concerted efforts to introduce the full suite of symbolic Christian Nationalist policies into these states.

Figure 2. Heat map of Project Blitz bill introduction in state legislatures 2019-2021.

Source: Blitzwatch

Table 1. Types of Project Blitz bills introduced

Source: Blitzwatch

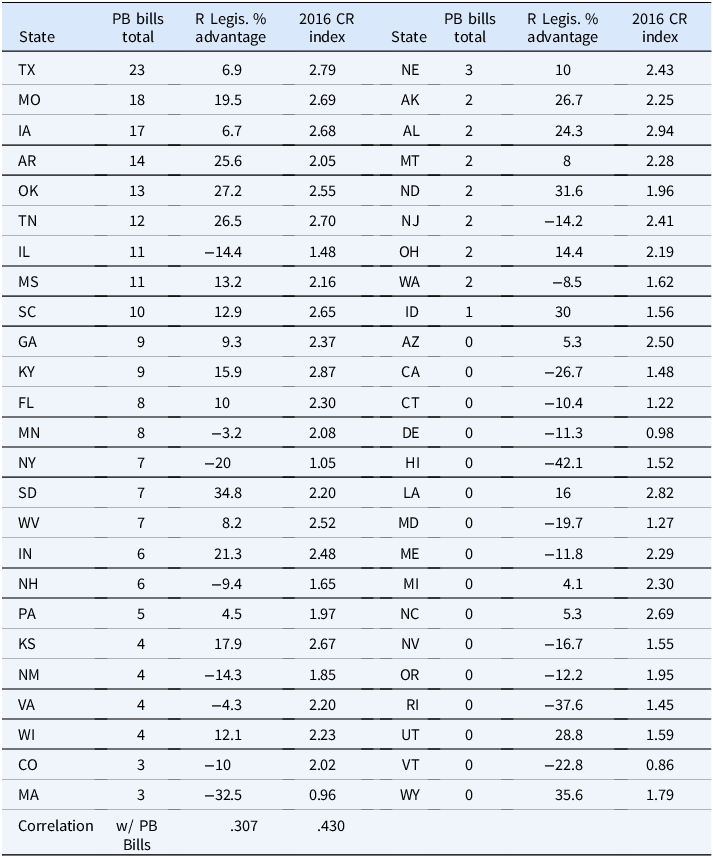

Table 2. Project Blitz bill introduction, and Republican legislative advantage 2019-2021. Christian Right influence index, 2016. All by State. Ordered highest to lowest Project Blitz bill introduction

Data Sources: BlitzWatch, National Conference of State Legislatures

In order to evaluate the role of existing Christian Right organizations in facilitating the activity of Project Blitz and the introduction of their bills, the primary independent variable, I use a measure of the Christian Right’s influence in state politics for 2016. This measure of Christian Right influence is a continuation of a time series measuring the influence of the Christian Right at the state level conducted in 2000, 2004, and 2008. In order to gauge the level of influence that the Christian Right exerts in a state’s politics, I created an index that encompasses respondents’ assessment of the movement’s influence in the overall Republican politics of the state, the 2016 presidential campaign in the state, state-wide elections, district elections, and ballot initiatives or referenda where appropriate. Each area of possible influence was separated into two questions, one about the activity of the Christian Right, the other about the impact of the movement in that particular political sphere. In this way, I capture both the intent to influence and the outcome of the influencing activity. (For more information on the construction of the indices, see Appendix A, and for more information about the survey on which the index is based, see Appendix B).

While a measure more parallel in time to the Project Blitz data might be desirable, 2016 is the most recent iteration of the data collection. Given that it is intended to operationalize a long-standing and institutionalized social movement, the 2016 measure of CR influence should be a good measure of the state political environment Project Blitz entered with its first attempts to introduce legislation in 2017 and expanded its reach during the timeframe under study here in 2019-2021.Footnote 1 While the temporal difference between the measure of the dependent variable and the primary independent variable suggests caution in interpreting the results of my model, there is no reason to suspect results reflect a spurious relationship.

Table 2 reports the Christian Right influence index scores for 2016, as well as the total number of Project Blitz bill introductions for 2019-2021 for each state and the proportion of Republican majority in each state’s legislature. While the Christian Right influence index has varied by state for each year of the data collection, there are several overall trends that are in evidence in the 2016 influence index. Most southern states demonstrate higher levels of influence, while the Northeast and Pacific coast states demonstrate much less. There are a few outliers in the 2016 data, for example, New Jersey appears in the top half of states with an index measure of 2.4. While there is no obvious narrative to explain liberal New Jersey’s place higher in rankings, the fact that the state had several Project Blitz bills introduced in the 2019-2021 time frame suggests that there may have been an underlying shift toward religious conservatism during the Trump years.

In order to account for other possible reasons for the number of Project Blitz bills introduced in a state, I include in the model a set of control variables to measure both the religious and ideological context of state politics (proportion of Evangelicals in a state, Trump 2016 vote percentage) and the partisan control of the state legislature during the time frame of the study (2019-2021). This is a minimal set of controls designed to account for the most likely other reasons for Project Blitz’s success; other controls were tested, but this narrower model better preserves degrees of freedom in a small data set and thus produces more robust and reliable model coefficients.

Because the dependent variable consists of count data (the number of Project Blitz bills introduced) and because there is a non-trivial number of states where no Project Blitz bills were introduced at all, I use a zero-inflated, negative binomial logit model to analyze the data.Footnote 2 In order to analyze a data set where there are a significant number of zeros, we need to specify a control variable that would likely explain why a particular case is likely to have a zero as its count for Project Blitz bills introduced (Long Reference Long1997; Long and Freese Reference Long and Freese2006). For this analysis, I use a characteristic of each state legislature, the proportion of advantage Republicans had overall. If a state’s legislature has few Republicans, it is less likely that there would be Christian Nationalist legislation introduced.

Results and discussion

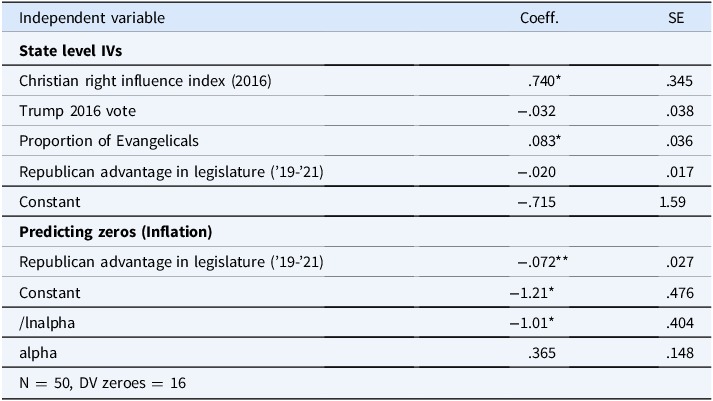

Table 3 presents the results of the data analysis, and Figure 3 presents the marginal effects of the independent variables on the introduction of Project Blitz bills in a state. There is a clear and significant relationship between the perceived level of Christian Right influence in 2016 and the overall number of Project Blitz bills introduced in 2019-2021. Further, the proportion of self-identified Evangelicals in a state is significantly related to the PB bill introduction. None of the other independent variables, including the proportion of Republican advantage in a state’s legislative branch, had a significant effect on the number of Project Blitz bills introduced. The lack of influence of Republican advantage in the state legislature suggests that the impact of the Christian Right influence on bill introduction is evidence of an outside process of mobilization and persuasion, not simply an artifact of Republican control.

Figure 3. Graph of marginal increase of Project Blitz bills introduced based on independent variables. Dependent variable: Total PB bills introduced by state 2019-2020.

Note: Graph based on predicted marginal increase of the number of Project Blitz bills introduced based on an incremental increase in independent variable coefficients. These coefficients are based on Zero-inflated, negative binomial logit. Data sources listed in text.

For the prediction of zero values for the dependent variable, we see that the Republican advantage in a state legislature is significantly negatively related to the introduction of ZERO Project Blitz bills in a state. This makes sense because when Democrats have an advantage in the state legislature, it is much less likely that Project Blitz bills will be introduced, thus appropriately explaining the high number of zeros in the counts of bills introduced in each state.

Table 3. Christian Right influence in 2016 on Christian Nationalist bills introduced in state legislatures 2019-2021 (Zero inflated negative binomial)

Log likelihood = −117.976, LR chi2 = 12.62, Prob > chi2 = 0.013

^p < .1 *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; two-tailed

Dependent variable —Count of Project Blitz bills introduced in state legislatures, 2019-2021

Note: Data sources listed in text.

What these results demonstrate is a clear relationship between the historical movement known as the Christian Right and the contemporary Project Blitz, an organization formed to pursue Christian Nationalist policies in state legislatures. Project Blitz is an important organization and effort in and of itself, seeking to exploit the reality of state legislators’ reliance on outside groups for bill writing to further its agenda. But the key takeaway from this result is the continuity between the old Christian Right and newer Christian Nationalism. Not only have scholars documented the ways that Christian Nationalist ideas have their roots in the fringes of the Christian Right, but now we have evidence of the direct link between those existing organizations and power structures and more contemporary attempts to change policy.

The results also point to the continuing importance of the proportion of Evangelicals in explaining bill introductions in state legislatures (Cleary and Hertzke Reference Cleary and Hertzke2006; Djupe and Conger Reference Djupe and Conger2012). The more Evangelicals in a state, the more likely Project Blitz legislation will be introduced; this effect exists over and above a state’s vote totals for President Trump in 2016, which was not significant in the model. This reminds us that even though church attendance is down across the United States, Evangelical identity still makes a significant impact on individuals’ policy positions and vote choices. The presence of Evangelicals gives credence to Project Blitz objectives and makes it more likely that legislators will listen to the group’s arguments—or agree with them themselves.

These results show that Christian Nationalism is more than just a set of voter attitudes and opinions; it is also an evolving set of institutions and leaders who are actively seeking to change policy. Based on the earlier work of its progenitors and compatriots in the Christian Right, Christian Nationalist policy is being pursued with an insider strategy, changing laws at the state level, seeking to impact the foundation of how we approach democracy and its relationship to religion. This data analysis demonstrates that the current power and influence of Christian Nationalist attitudes and activities is based on the historical influence of the Christian Right social movement. It suggests we take a different approach to examining Christian Nationalism, looking less at the political and social attitudes of supporters and voters and more at the organizations, personnel, and policy aspirations of the mobilized CN movement. This focus will lead us to answer important questions about the resources Christian Nationalist activists and politicians have at their disposal, as well as the outlines of potential policy initiatives based on CN attitudes and ideas. A Christian Nationalist movement that was born with the election of President Trump would look and behave very differently from one that can draw on the accumulated experience, power, and institutional penetration of decades of Christian Right activism. A Christian Nationalist movement with a historical pedigree has a much stronger chance to both pass and implement its policy goals because the fields were plowed and ready from earlier activities of the Christian Right.

Conclusion

Project Blitz has had some success in passing its bills in state legislatures, but not without controversy or opposition. The leaders of Project Blitz efforts in many states—usually as leaders of a Prayer Caucus affiliate—are not registered to lobby, and this should draw the attention of both scholars and journalists to the informal networks of conservative Christians in many states. Individual legislators have certainly faced scrutiny for their ties to Project Blitz. In Ohio, state legislator Timothy Ginter claimed to have never heard of Project Blitz in order to deflect criticism for the bills introduced and back-channel influence exerted by PB on the Ohio legislature. It was later revealed that he had been the co-chair for the Ohio Prayer Caucus (affiliated with the National Prayer Caucus), giving the lie to his knowledge of Project Blitz and its activities (Glenza Reference Glenza2019). Like the Christian Right before it, Christian Nationalism seems most effective in situations where they can negotiate and make decisions in private or focus on technical issues not widely understood (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960). Public scrutiny and a focus on issues with wide attention and applicability tend to favor their opponents.

This article empirically demonstrates the link between Christian Nationalism and the institutionalized and wide-ranging Christian Right social movement that forms its foundation and the political context in which the CN operates at the state level. It also focuses needed attention on the practical outcomes of Christian Nationalist political attitudes, the organizations and public policy that are the outgrowth of beliefs about the role of religion in the United States’ founding and present political reality. Observers’ perception of the level of influence wielded by the Christian Right in state politics in 2016 is directly related to the ability of Project Blitz, a central Christian Nationalist organization, to introduce its model legislation three to five years later. Christian Nationalism is built on the thirty-year foundation of the Christian Right movement and can draw supporters, resources, and experience from that base. While scholars’ demonstration of the troubling aspects of individual attitudes linked to Christian Nationalism is important, it may be even more important to understand Christian Nationalism’s policy goals and the organizational infrastructure it has at its disposal to pass and implement those goals.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048325100217

Competing interests

The Author Declares None.

Kimberly H. Conger is Associate Professor of Political Science in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Cincinnati. Her work on religious activists and interest groups in state-level politics has been published in Political Research Quarterly, Perspectives on Politics, and State Politics and Policy Quarterly.