Encounters with material objects lie at the heart of Mormonism's origin story. The story goes like this: Late one night in September 1823, an angel visited the bedside of a young Joseph Smith to tell him of one of these objects—a sacred book written on plates of gold, buried on a hillside not far from the Smith family's farm in upstate New York. When, the next day, Smith found the gold plates as directed, the divine being reappeared with further instructions. This time, he forbade Smith from removing the plates but beckoned him to return to the site year after year. In 1827, on Smith's fifth annual visit, the angel finally allowed him to collect the plates and take them home. Over the next several months, Smith kept them securely hidden and revealed them only to a select group of witnesses. Using a seer stone, he translated the plates’ inscriptions from their mysterious language into English. Trusted companions served as scribes. The translation revealed that the plates were created several hundred years before the birth of Christ by the angel Moroni and his father Mormon, and recorded the extraordinary history of their Nephite clan, which had migrated to the American continent from Jerusalem. In June 1829, shortly after the translation was complete, Moroni directed Smith to return the gold plates (in some accounts, by depositing them in a cave). Smith obeyed. Then Smith arranged for the publication of the manuscript in nearby Palmyra, which appeared in 1830 as the first edition of the Book of Mormon.Footnote 1

If the gold plates are not to be excluded outright from consideration, regarded as fakes or as part of a tall tale, then how might they be incorporated into scholarly explanations? Historians of religion who have confronted this question have approached the story of the plates sympathetically in an effort to recognize its meaning and efficacy for Smith and other early Mormons. By and large, they rely on two interpretative paradigms: religious imagination and cultural context. They treat the plates primarily as the product of Smith's fertile religious imagination or as an organic expression of the cultural milieu of nineteenth-century American spirituality, or as some combination of the two.

While there have been many nuanced interpretations of Smith's motivations and the broader phenomenon of Mormon origins, few have considered the possibility that Smith, and other witnesses, could have physically encountered material plates at some point during the religion's formative years. This, in spite of the fact that descriptions of the plates by Smith and other witnesses share details that suggest that they were seeing and touching ordinary material things with a consistent set of characteristics. These witness accounts, moreover, portray the plates as possessing qualities remarkably similar to those of nineteenth-century industrial printing plates, especially stereotype plates or copper plates (Figures 1 and 2). Printing plates, like Smith's gold plates, were metallic, were covered in writings that read from right to left, were heavy when collected together, typically came in a set, and approximated the dimensions of the pages of a book. This article proposes that Smith, and potentially several witnesses, had a foundational encounter with printing plates during the 1820s. It also suggests a range of possibilities regarding the nature of that encounter. It could have been that Smith's gold plates, which he handled and showed to his followers, were actual printing plates that he had acquired. Or, short of Smith physically obtaining this printing technology, Smith might have examined it at some point and later constructed a homemade facsimile that was informed by the details of his firsthand observations, or, at least, developed his verbal and written descriptions of the ancient Nephite relics from that prior experience with the same.

Figure 1. A stereotype plate used to print page 482 of James Rush, The Philosophy of the Human Voice (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. [with the cooperation of the Library Company of Philadelphia], 1855). 4.125 x 7 inches. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Figure 2. Copper plate engraved by J.H. Daniels, with corresponding printed frontispiece. 5.5 x 9 inches. Miscellaneous Matrix Collection. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

However Smith made first contact, the distinctiveness of the argument is that it does not relegate material things to the status of secondary byproducts of human action, as if the plates—and perhaps Mormonism itself—sprang solely from Smith's mind or from broader cultural forces radiating through him. The point in arguing for a material basis to the plates is hardly to deny a role to creative minds and cultural contexts. Instead, it is to regard the generative encounter between humans and material things as basic to scholarly thinking about what catalyzes religious change.

This suggestion that things and humans act in irreducible combination draws inspiration from several theoretical conversations about materiality, sometimes grouped as forms of “new materialism.” The basic premise of my approach, advanced on the basis of textual and material evidence, is that material things make a difference, such that it is insufficient to think exclusively within a framework of primary human actors and secondary material instruments or patients. The aim is not to reverse the terms of that agency relationship, as in a material determinism, but, rather, to locate a different starting point for understanding creativity and change that regards as significant the contributions of both humans and things. Conceived in those terms, the relationship between Smith and his plates might be productively understood as what some new materialists call an assemblage, defined as a grouping of human and nonhuman elements that work together collaboratively. Their interactivity is essential to the assemblage's influence.

By arguing for a foundational encounter with printing plates (or, in new materialist terms, for conceiving material printing plates as nonhuman actors in an early Mormon assemblage), this article pursues two goals. First, it demonstrates how attention to the material qualities and capacities of things, here printing plates, allows for a more complete understanding of the emergence of Mormonism on the basis of the available evidence. Second, beyond this specific case, it provides an occasion for broader methodological and theoretical reflection on the destabilizing and generative powers of encounters with material things, as well as on why those powers are regularly overlooked. My hope is that, whatever the reader makes of this speculative contribution to the study of Mormon origins, the approach modeled here will also speak to kindred pursuits in the study of other regions, periods, and religious traditions, prompting questions about what other material things might lie hidden in plain sight and how thinking about the assemblages in which they participate could lead to the development of different narratives in even well-trodden areas of study.

The article explores these ideas, beginning with a discussion of the role of the gold plates in the historiography of early Mormonism, observing that the question of the plates’ materiality has not yet been sufficiently addressed. Then it presents the printing-plates hypothesis as a way to contend with that question. A first subsection introduces printing plate technologies; a second subsection triangulates textual descriptions of the gold plates with contemporary material-bibliographical evidence in terms of eight physical qualities (color, dimensions, weight, orientation, characters, imagery, textual format, and binding); and a third subsection assays scenarios of how Smith, and possibly a group of witnesses, might have encountered printing plates in upstate New York in the 1820s. The article ends with conclusions regarding method. Throughout, it draws on extant sources about the plates, the majority of which are collected in the five-volume Early Mormon Documents (1996–2003), edited by Dan Vogel, and the ongoing Joseph Smith Papers (2008–), a multivolume editorial project based in Salt Lake City.Footnote 2

Historiography, Method, and Materiality

Most historians of religion have approached the story of the gold plates by wielding two powerful interpretative tools: religious imagination and cultural context. They explain the plates as part of the creative religious vision of Joseph Smith, one that emerged organically out of the popular religious traditions that flourished in antebellum America, in which Christianity and magic intermingled and wherein signs, wonders, visions, and apparitions were common.Footnote 3 These ways of thinking have allowed scholars to thread the needle between empathy and suspicion and regard Smith's concept of the plates as more than a mere attempt to deceive, for good or ill. Rather, the concept was an expression of his religious vision, in ways consonant with his cultural and religious milieu. It is in this qualified sense that scholars grant that the gold plates were real—real only for the religious people they study.

While appeals to the power of culture and imagination are essential techniques for any historian of religion, in the case of early Mormonism, they leave a fundamental question unresolved. If Smith imagined the plates, what are scholars to make of the abundant firsthand testimonies, by Smith and his followers, to their concrete materiality? Always, Smith himself insisted that the plates were real in the ordinary, naturalistic, and unqualified sense of that term. He also provided precise descriptions of their material characteristics. They were golden or metallic in color and about six by eight inches in dimension apiece. Together, they weighed around forty pounds and were bound together by rings. They were covered with writing in an esoteric language, reading right to left, which Smith dubbed “reformed Egyptian.” Smith provided details across several of his accounts, such as in his 1842 correspondence with the newspaper editor John Wentworth, called the “Wentworth letter” by scholars:

These records were engraven on plates which had the appearance of gold, each plate was six inches wide and eight inches long, and not quite so thick as common tin. They were filled with engravings, in Egyptian characters and bound together in a volume, as the leaves of a book with three rings running through the whole. The volume was something near six inches in thickness, a part of which was sealed. The characters on the unsealed part were small, and beautifully engraved. The whole book exhibited many marks of antiquity in its construction and much skill in the art of engraving.Footnote 4

Smith was not the only person who claimed direct sensory experience with material plates. The testimonies of eight of Smith's early followers proffer supporting evidence to suggest that the plates were objects with a coherent set of features. These eight (all members of the Smith or Whitmer families) testified that they, together, saw and handled them, likely in late June 1829.Footnote 5 Their official statement, known as the “Testimony of the Eight Witnesses,” appears in the paratextual material of nearly every copy of the Book of Mormon:

Be it known … that Joseph Smith, Jr. the Author and Proprietor of this work, has shewn unto us the plates of which hath been spoken, which have the appearance of gold; and as many of the leaves as the said Smith has translated we did handle with our hands; and we also saw the engravings thereon, all of which has the appearance of ancient work, and of curious workmanship. And this we bear record with words of soberness, that the said Smith has shewn unto us, for we have seen and hefted, and know of a surety, that the said Smith has got the plates of which we have spoken. And we give our names unto the world, to witness unto the world that which we have seen. And we lie not, God bearing witness of it.Footnote 6

All eight witnesses stood by the testimony throughout their lives. For instance, in 1838, Hyrum Smith was pressed by an interlocutor as to whether he might have seen the plates only with his “spiritual eyes” rather than physically. He insisted that “he had but too [two] hands and too [two] eyes[;] he said he had seene the plates with his eyes and handeled them with his hands.”Footnote 7 Further, while the members of the Whitmer family dissented from Smith's leadership in the 1830s, they never failed to uphold their accounts of the plates.Footnote 8 The testimonies of the eight witnesses may be contrasted with those of the three other most important witnesses in the Mormon tradition, namely, the authors of the “Testimony of the Three Witnesses,” who professed to having witnessed the plates spiritually, in a vision, but not physically. This distinction would have been less imperative had there been no physical plates at all. While the “Testimony of the Eight Witnesses” is not itself dispositive, it is significant in that it corroborates Smith's account.

Building outward from those sources that are most firsthand, another concentric layer of witnesses reported experiences with physical plates. These others did not claim to view or handle the plates directly but, rather, reported that they saw, felt, or lifted them while wrapped in a cloth or concealed in a box. Josiah Stowell, a neighbor and longtime friend of the Smiths, maintained that he was the first person to take the plates from Smith when he carried them into the family home (probably wrapped in Smith's coat).Footnote 9 Joseph Smith's sister Katherine also spoke of taking the plates from Smith when he arrived home with them and laying them on a table. She later described lifting the plates in the cloth, feeling that they were “separate metal plates,” and hearing “the tinkle of the sound that they made.”Footnote 10 Lucy Smith, Joseph Smith's mother, told a neighbor that, though it “wass not fur hur to see them,” she “hefted and handled them.”Footnote 11 It is clear that Lucy, at least, was convinced that what she felt was the real thing, for, in 1828, she discussed with friends a plan to display the plates and charge twenty-five cents admission.Footnote 12 Another neighbor, one Mr. Beman, retrofitted an old glass box to store the plates, by sawing off the ends. When Smith put the plates inside it, Beman noted that he heard their “jinking” noise.Footnote 13 Several other neighbors, along with Joseph Smith's brother William, reported lifting the plates wrapped in a pillowcase.Footnote 14 Of the aforementioned three witnesses, Martin Harris added that he, too, lifted the plates in a box with a cloth draped over them, and Oliver Cowdery testified to handling the covered plates during the translation process.Footnote 15

An especially compelling account of this latter type comes from Emma Smith, Joseph Smith's wife, who reported several interactions with objects. In an interview, she remarked, “The Plates often lay on the table without any attempt at concealment, wrapped in a small linen table cloth, which I had given him to fold them in.” She noted that she often “moved them from place to place on the table, as it was necessary in doing my work.” In another interview, she mentioned that the plates “lay under our bed for a few months but I never felt the liberty to look at them.”Footnote 16 Emma's matter-of-fact accounts of the plates—they literally got in her way—lend support to the hypothesis that the plates were real physical objects. Her comments were not framed as any kind of argument bent to persuade or prove. At the same time, the ordinariness of Emma's testimony is of a piece with the others in that nothing bombastic or extravagant was alleged, only that here was something solid that one could hold in one's hands. Though none of these sources are conclusive on their own, when triangulated with the accounts of Smith and the eight witnesses, they contribute to the sense that there was some really existing object with a coherent set of characteristics. Taken together, the details that resonate throughout the many accounts—the feel of separate pieces, the clink of metal on metal, the bother of hauling them from one place to another—have the ring of truth.

My larger point is that the plates persist across early accounts as real objects. While only Smith and the eight witnesses claimed to have seen and handled the plates directly, a number of others—the devoted, the curious, the skeptical, and the hostile among them—touched, lifted, or saw them in a concealed state. If one takes a careful approach to these testimonies, accounting for their varying degrees of reliability, an image comes into view of a set of objects with specific qualities. These physical objects, as described, are hard to square with scholarly explanations rooted in the idea that Smith experienced a spiritual vision of the plates. While it is apposite to recognize the richness of Smith's imagination, as well as the contextual prevalence of visionary experiences in antebellum New York, nevertheless, these accounts also refer to real physical things, existing external to visionary imagination. How are researchers to account for the material presences of these objects, which were at once tangible and fantastic, both in this world and out of it?

One recent answer to this question comes from Ann Taves, a contributor to the growing area of the cognitive science of religion. In Revelatory Events, her book on new religious movements, and in an earlier article on Mormonism, Taves argues that the plates were not materially real—at least not originally, when Smith said he recovered them in 1827—but later underwent a process of “materialization” among believers, owing to the stunning reality-producing powers of the human brain.Footnote 17 She posits the following narrative. Smith, who was from adolescence a “skilled perceiver,” first experienced a vision in 1823, in which the angel visited his bedside, told him of miraculous plates, and indicated that he would supply them to Smith when the time was right. In 1827, after four years of waiting, Smith realized that the angel was now compelling him to take a “more active course” and “actively materialize the plates ‘in faith.’”Footnote 18 As part of this materialization, Smith likely set to fabricating plates using raw materials, perhaps, first, by pouring sand into a box and, later, using tin or lead.Footnote 19 Taves's key point is that Smith did not contrive his own material plates to defraud anyone. It was his way of making good on his sincerely held belief. He created homemade plates “in the knowledge that they would become the sacred reality the Smith family believed them to be,” an act of substantiation not unlike how a priest performs the Eucharist.Footnote 20 A final stage of materialization was social acceptance, fulfilled when the two major groups of witnesses also became able, through their devotion, to “see” the sacred plates. “Seeing,” on this understanding, was a social and phenomenological experience: It meant participating in a shared vision of the plates that affirmed their spiritual reality—whether or not the seers actually had direct access to Smith's crude homemade version. Consequently, the witness statements “should not be taken as testimony to the ordinary materiality of the plates” but, instead, “to the power of human minds to see things together in faith.”Footnote 21

The present study shares with Taves an approach to early Mormonism that foregrounds the relationship between mental processes and material things. The main differences between her account and mine have to do with the moment at which material things enter the narrative and the power and significance they wield once they are there. In Taves's telling, Smith's mental idea of the plates preceded their handcrafted physicality, hence, her notion of a linear process of materialization whereby underlying mental processes later assumed a secondary concrete existence in the homemade plates. Moreover, what Taves regards as most important about the process of materialization was not the physical externalization of the plates, per se, but the way in which the witnesses became able to see the plates “in faith” or, in other words, internally, in “cognitive and social psychological processes.”Footnote 22 That is, while Taves says that physical externalization (qua homemade plates) was a likely scenario, ultimately she argues that psychological processes were functionally effective whether or not a witness actually ever encountered anything material, felt in the hand or seen by the eye. Objects were real insofar as they were productions of the mind. In her account, cognitive processes retain priority, in chronology and in significance.

This article posits that the beginnings of Mormonism may be better understood as arising from an assemblage of ideas and concrete material things rather than as a materialization of an idea into a material thing. Attributed to Deleuze and Guattari, the idea of “assemblage” has gained momentum among a number of thinkers who are sometimes styled as “new materialists” (though many resist the label).Footnote 23 While usage varies, these thinkers usually invoke the term assemblage to describe any grouping of human and nonhuman components whose influence is a consequence of their collaborative work together. Thinking in terms of assemblages is to view material things and human mental processes as collaborators on a common plane. It is not simply a reversal of the terms. The point is not to prioritize material things above or before human or mental activity, as in a material determinism. It is just to avoid privileging one sphere over another. Advocates of this approach demonstrate how the elements of an assemblage augment and extend the powers of other elements, underlining how none can be isolated as the exclusive source of agency or motive power.

Forms of theory that prompt scholars toward consideration of human–nonhuman assemblages are found in a capacious array of sources beyond the “new materialist” canon that emerges from the European and Anglo-American tradition of critical theory. Congenial ideas may be found across regions, periods, and schools of thought, including various Indigenous American, Southeast Asian, and Africana philosophies.Footnote 24 This article also takes its cues, for instance, from emic Mormon approaches to matter that express similar theoretical sensibilities in different terms. Many scholars have analyzed Mormon theology's insistence on the radical immanence of matter and spirit, as well as its exaltation of the quotidian material world as a source of divinity.Footnote 25 They have also explored how, on the level of lived religion, Mormonism claims a long history of embracing the interplay between religious ideas and physical things, not only in the case of the plates but also with seer stones, papyri, garments, healing handkerchiefs, railroads, optical media, accounting books, and religious artwork, among other examples.Footnote 26 The tradition “allows for intelligence in a variety of embodiments,” as John Durham Peters and Benjamin Peters put it.Footnote 27 It is not surprising, then, that believing Latter-day Saint scholars working across disciplines have found productive conversation partners among self-styled new materialists and allied thinkers.Footnote 28 While I approach the problem of the gold plates from a naturalistic point of view, my theoretical questions have been inspired and refined through engagement with these materialist ideas and practices from within Mormonism.Footnote 29

Drawing on these myriad ways of theorizing the power of material things, this article argues that the physical plates made a difference in the early Mormon assemblage. Their role can be understood, first, as a material prompt, providing Smith with the occasion and the confidence to undertake their translation and share revelations with others. This is not least because, as objects that Smith likely perceived as enigmatic, or, at best, partially understood, Smith would have experienced the encounter as destabilizing and requiring interpretation. One could also say that his possession of the plates for almost two years enabled a number of prolonged practices and relationships to gain traction, for instance, by furnishing a duration of opportunity for Smith to gradually share them with witnesses, translate them, and proclaim revelations. Most important, perhaps, is to ask whether Smith would have ever thought to undertake, and then assiduously pursued, a translation of writing that was materially nonexistent or if he would have regarded himself as specially chosen to lead had he not received a cue from this unique material encounter. This is not to say that it would have been otherwise impossible for Smith to have done these things, only that scholars who wish to explain his actions without recourse to objects such as printing plates must lean quite heavily on the bottomless creativity of his imagination. These events are far more comprehensible when regarded as unfolding around real material things.

They are more comprehensible still when understood in connection to physical things with the distinctive qualities of printing plates. These qualities mattered in the same way that the qualities of a typewriter stimulate different behaviors than do, say, those of a gun or a coffee cup or a bouquet of flowers. The material specificities of the stack of plates enabled Smith and, perhaps, also witnesses to regard it as a book because of its dimensions and multiple leaves; to infer that the book was of Israelite origin, owing to the right-to-left orientation of the lettering; and to treat it as a precious rarity, in part because of its metallic sheen. The substance of metal may have struck Smith as an appropriately hardwearing medium for eternal truths, making him more likely to regard the set of plates as sacred and scriptural.Footnote 30 Again, I recognize that it remains within the realm of possibility that Smith—in the midst of a spiritual vision or in the course of his more workaday experience—conjured up these material details out of sheer ingenuity or imaginatively fashioned a pastiche of scattered notions.Footnote 31 But is it not more plausible that he described and interpreted the plates in these ways because he viewed and handled a physical object with just those characteristics? Though the contents of the Book of Mormon may be said to be largely a product of Smith's imagination, as shaped by cultural factors, one may also say that Smith was prompted to begin such a production in the first place, and to proceed in the way he did, by the materiality of the plates that he beheld and handled.Footnote 32

The concept of assemblage, which directs attention to the material qualities of things and how they interact with human thought and practice, informs another term, encounter, recurring in this article. Encounter is a term that remains undertheorized in new materialist scholarship despite its frequency of use. I use it here to mean that to encounter something or someone—whether an object, a space, a person, a mood, and so on—is to enter into the other's “field of force” (to borrow a phrase used by Charles Taylor) and, thus, to assemble with the other, be made vulnerable to change in oneself, and become different.Footnote 33 Such encounters expand the field of what was before possible. They rescript future events. This is what I have in mind when I say that the materiality of the printing plates mattered, in the sense that Smith's encounter with them changed his course and continued to direct that course in particular ways. As I hope to explore here, encounters with difference, and the assemblages that crystallized around them, are essential for understanding how religious change happened. They may rupture cultural context, destabilize human beings, reshape thoughts, spark improvised practices, set off unexpected chains of events, lend new percepts to inherited concepts, and, generally, open up a space of the new, to everyone's surprise.

If this study seeks to advance scholarship on early Mormonism by focusing on an encounter and assemblage with material artifacts, in another sense it takes a step back. In contrast to today's scholars of religion, several nineteenth-century observers suggested that Smith could have found printing plates. In 1835, the Baptist newspaper The Pioneer, based in Rock Spring, Illinois, ran a story by a writer, identified only as “A Friend of Truth,” who speculated that Smith obtained copper printing plates to show his followers: “The probability is that Smith, who had been a book-pedlar, and was frequently about printing establishments, had procured some old copper plates for engravings, which he showed for his golden plates.”Footnote 34 The story, with its fabrication about book peddling (no other sources suggest that Smith had ever been employed this way), was reprinted verbatim in several religious and secular periodicals, including in New York City, Raleigh, and Exeter, New Hampshire.Footnote 35

Stories about Smith's use of stereotype plates circulated as well. In her popular school textbooks, the reformer and educator Emma Willard described, as fact, how Smith misled followers by showing them the stereotyped plates of the Book of Mormon and claiming that these were the plates that he had dug up. The story first appeared in the enlarged 1849 edition of her Abridged History of the United States, which was reprinted well into the 1870s, including translations in Spanish, German, and French.Footnote 36 (Willard's timeline was off the mark; Smith had said that the gold plates were in his possession from 1827 to 1829, but there existed no stereotyped edition of the Book of Mormon—and, therefore, no stereotyped plates to print it—until 1840.Footnote 37) In 1903, the printer and popular author Elbert Hubbard supplied another gloss on the stereotype idea, writing that Smith must have acquired a set of stereotyped plates and then buried them in the hill so that he could dig them up again. Hubbard speculated that the plates were in another language (“Dutch or Something”), which is why the eight witnesses could not read them and accepted Smith's claim that they were Reformed Egyptian characters.Footnote 38 My argument echoes these long nineteenth-century explanations in that it puts a material object at the center of Mormonism's origins. All these accounts, whether or not they understood Smith as acting in good faith, tried to explain how Smith, and his followers, could have been so sure about the plates. They all stipulated that there must have been something that Smith handled and showed to witnesses.

The present study also builds on Latter-day Saint scholarship on the plates. By reading witness testimonies as accounts of real material plates, I find myself in the company of several “believing scholars” who have drawn similar conclusions about them, in contrast to “unbelieving scholars” (to invoke the Latter-day Saint terms for Mormon and non-Mormon scholars of Mormonism, respectively). For instance, Terryl Givens argues that the abundance of witness accounts ought to guide interpreters away from “the realm of [Smith's] interiority and subjectivity”—that is, from the idea that the plates belonged to his visionary experience alone—“and toward that of empiricism and objectivity.” Richard Lyman Bushman has further written that unbelieving scholars, uninterested in or made uncomfortable by empirical questions, “repress” the witness accounts. In his words, “Skeptics have to minimize quotations from the participants or else the plates take on all too real a life.”Footnote 39 While I part ways with Givens and Bushman when they take an additional step to conclude that those plates were Nephite relics, nevertheless, I agree with their general approach to the witness testimonies as referring to existing things, by virtue of their concrete detail and abundance, which is compatible with the naturalistic view I take. Beyond believing scholars such as Givens and Bushman, however, to my knowledge, there are no scholars of religious history who have seriously engaged with the possibility that Smith encountered a material something, let alone tried to figure out what that something was.

It is worth pausing on that omission. Why has the simplest answer to the mystery of the plates—that Smith had access to material plates—rarely been considered by critical historical scholarship? Why has it been more intuitive to accept, on the one hand, that Smith and other early Mormons believed in, or experienced a collective vision of, nonexistent plates, or, on the other hand, as Taves suggests, that they fabricated plates from scratch, spurred by highly complex cognitive processes? Partly, this has to do with an aversion among scholars of religion regarding empirical questions about anything supernatural, as Bushman implied.Footnote 40 Further underlying the historiography may be an implicit presumption that mental constructs (including beliefs, imaginations, desires, cultural symbols, and cognitive structures, both individual and collective) necessarily precede and give rise to material things in the world. Even though much excellent work in the area of material religion has directed scholarly attentions to the material things that inhabit religious cultures, there may be a lingering resistance to investigating objects that do not, in the first place, express an idea priorly present in an individual religious imagination or a collective cultural mentality. Simply put, human mental constructs tend to remain more important, more fundamental, and, ultimately, more convincing to scholars as explanations for religious phenomena. (I discuss some reasons for why this occurs in the conclusion.) It is undeniable that approaches emphasizing mental constructs have fostered formidable advancements, not to mention that visionary experiences are common in the history of religions. When those approaches become a theory-of-everything, however, they may cause scholars to miss more down-to-earth realities. When scholars presume that religious desires, ideas, or thoughts must inspire or precede their application onto a material thing, they can overlook how things themselves can inspire or modify thoughts, as in an assemblage with multiple interconnecting elements, human and nonhuman.

The Printing-Plates Hypothesis

This section has three parts. The first part presents a brief introduction to printing from plates in the early nineteenth century. The second part analyzes textual descriptions of the gold plates, demonstrating how their imputed characteristics are largely consistent with printing plates, as seen in the material-bibliographical record. The third part presents three speculative scenarios of how Smith could have chanced upon printing plates in upstate New York in the 1820s.

Printing from Plates

Printing from plates—both stereotype plates and copper plates—was common in the nineteenth century. In the 1820s, stereotypy was a new technology, first used in the United States in 1814, and on the upswing in the printing trades and right on the verge of becoming the dominant method for the mass reproduction of texts and images, especially bookwork.Footnote 41 Before its advent, Western books were printed almost exclusively from moveable types, not from plates. That process, in the early nineteenth century, was virtually the same as Gutenberg's: A compositor set each page from hundreds of tiny lead types (and sometimes also image blocks) which were installed in the printing press alongside other composed pages. Printing from moveable types was an efficient system except for the fact that the types needed to be continually released back for reuse to avoid tying up capital in what was called standing type. Thus, most books printed from moveable type—like the first edition of the Book of Mormon, at Palmyra—could not be reprinted without resetting, a major production bottleneck. Stereotypy changed book printing by eliminating the need to reset type for reprintings. To make a stereotype plate, a compositor first composed the types as if to print directly from them. Then, the stereotypist took a mold in plaster of Paris (later papier-mâché) of the full page of composed type (and, sometimes, incorporating wood-engraved image blocks). He would cast that mold in typemetal that hardened into a silvery rectangular plate with reversed and raised (i.e., relief) letterforms and designs. Once trimmed and finished, the plates were ready to be inked and printed. A stereotype plate may be seen in figure 1.

Copper plates represent another kind of metallic printing plate that Smith could have come across. To prepare a copper plate, an engraver used a burin to groove precise, shallow lines into its soft surface into which ink was applied. As an intaglio process (i.e., the opposite of relief), an impression was produced using a special rolling press that pushed the paper into the plate's inky hollows. Unlike stereotype printing, which was typically used for printing on a mass scale, copperplate printing was usually considered deluxe in the early nineteenth century. Each plate required meticulous skilled labor to produce and, ultimately, yielded only a few hundred crisp impressions. Aesthetically, the result could be quite refined. For these reasons, copper plates were most often prepared for printing standalone decorative images; banknotes, including counterfeit banknotes; and book illustrations in upmarket books, such as the frontispiece plate pictured in figure 2. Printers also opted for copper plates to depict texts or symbols in books, including cheaper books, when those letterforms or symbols were used so infrequently that there were no prefabricated types for them. This was the case, for instance, with shorthand manuals (shown in figure 8). Shorthand was a system for rapid writing using curvaceous letterforms. To print shorthand text, engravers produced copper plates for them, printers printed them in a separate press, and, finally, the binders tipped them in amid other pages of regular typeset or stereotyped text. Printing from copper plates was the most common form of intaglio printing for bookwork through the 1820s, when it became overtaken by printing from plates of steel.Footnote 42

Comparisons of Textual Descriptions and Material-Bibliographical Evidence

Stereotype plates and copper plates exhibit similar characteristics to the gold plates as described by Smith and other observers. The following summary of those characteristics draws from twenty-four such accounts, in print and in manuscript, the majority of which are included in the Early Mormon Documents and Joseph Smith Papers collections. I have prioritized the remarks of Smith himself and those witnesses who claimed direct sensorial experience with the plates. There are also several records from Smith's family members and associates who did not see the plates physically (and who may or may not have also seen them spiritually), but who recorded secondhand what Smith and other eyewitnesses said about them, and I consider these when they offer different or more detailed information beyond what appears in witness accounts. I exclude from consideration reports from those claiming to have seen the plates in a spiritual vision without also having encountered them physically.

One further note on sources. As historians have long acknowledged, early Mormon documents are tendentious, intertextually contradictory, and frequently describe events secondhand or retrospectively.Footnote 43 Scholars remain divided on the credibility of many of the existing accounts for these reasons. For instance, recently Taves has called into question the claims of material contact by the eight witnesses. On her reading, later testimonies prove that the eight saw and touched plates only in a spiritual sense, not physically.Footnote 44 Meanwhile, other scholars investigating the same documents, including Bushman, Givens, and the Joseph Smith Papers editors, argue that the eight witnesses were describing an actual physical encounter, on the principle that any contravening source needs to be triangulated with the larger body of textual evidence. The latter position is the one I take up here, both regarding Taves's challenges to the eight witnesses and, also, to other accounts that inform my case throughout this article.Footnote 45 Overall, early Mormon sources require interpreters to proceed with caution and not to take any one document as proof positive for the existence of the plates or for a list of their exact characteristics. It is only when collected together that the converging textual evidence increasingly comes to resemble a description of a set of printing plates.

Furthermore, if Smith (and possibly other witnesses) encountered printing plates, the value of their testimonies varies significantly depending on the nature of that encounter. Here, I consider Smith's accounts, in conversation with other witness and secondhand reports, to support two possible variants of the hypothesis. First, I think Smith alone could have encountered the plates and that he later described the plates to witnesses or fabricated homemade plates for them to handle. Second, it is also possible that Smith took the printing plates and showed them physically to his followers, possibly after modifying them in a minor way, such as by binding them together. Readers are encouraged to examine the evidence and consider for themselves which version of events seems more likely. In either case, however, the encounter with physical plates, as objects, lay at the center of Smith's religious experience.

The following subsections examine the textual evidence, in comparative perspective with the material-bibliographical evidence, with regard to eight key physical characteristics that are found in the various accounts: color, dimensions, weight, orientation, characters, imagery, textual format, and binding.

Color

Though the phrase “gold plates” tends to evoke an image of polished, solid-gold tablets, the sources do not speak in a single voice regarding their color. The eight witnesses testified in 1830 that the plates had only “the appearance of gold,” as did Smith in his Wentworth letter of 1842. The qualifying phrase “appearance of” would seem to indicate some hesitation around their hue—that perhaps the plates did not shine with an absolutely golden luster. William Smith, Joseph Smith's brother, said later in life that he understood that the plates were a “mixture of gold and copper.” Various accounts mentioned less precious metals as well. One neighbor noted that Smith told him that he found “metal plates”; another said he heard the Whitmer family describing “sheets or plates of Brass”; in 1834, the anti-Mormon polemicist E. D. Howe wrote that the Smith family's descriptions of the plates were vague, noting that they once described the plates as “brazen” (i.e., brass). Finally, in a transcript from a court case, the Smiths’ neighbor Josiah Stowell swore that he saw “a corner of it”—presumably peeking out from under a cloth—which “resembled a stone of greenish caste.”Footnote 46

What might be seen here as contradictions or challenges to Smith's story of the plates make more sense when the “gold plates” are regarded as literally metallic printing plates. Copper plates were made of pure copper, with a shiny polished surface on one side, perhaps suggestive of “the appearance of gold” or “a mixture of gold and copper” in the eyes of the small, enthusiastic community. If Stowell's idiosyncratic account is to be believed, it can be noted that exposure to the elements and the process of oxidation would cause the copper plates to take on a greenish appearance. Stereotype plates, meanwhile, were cast from regular typemetal, an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony. When cleaned, these plates would have looked luminously “metallic”—the antimony gave typemetal a silvery and lustrous finish on burnished areas—but would presumably not have been mistaken for anything gold-like. It is also possible that Smith fashioned homemade metal plates informed by an earlier encounter with printing-plate technology, so perhaps the colors noted by observers were the color of his fabrications. I take up this possible variant more thoroughly later in this article.

Dimensions

The dimensions of copper plates and stereotype plates are evocative of witness descriptions. Smith judged the plates to be about six by eight inches and as “not quite so thick as common tin” (i.e., a couple millimeters); Martin Harris, who felt the plates but did not see them, wrote that he estimated each to be around seven by eight inches and possessing “the thickness of plates of tin.” As recorded in the trial proceedings, Stowell judged the whole to be “about one foot square and six inches thick.”Footnote 47 First of all, it would have been odd for Smith, Harris, and Stowell to have been so exacting, offering precise numbers, had they been describing something they had envisioned but not encountered. Second, these given dimensions are comparable to those of printing plates, especially if Smith and Harris were referring to a single stack of plates and Stowell to the entire set of objects—presumably, two stacks side by side. The stereotype plate shown in figure 1, preserved by the Library Company of Philadelphia, is 4.125 × 7 inches in dimension, with a thickness of 2.2 millimeters. Smaller than Smith's plates, it is offered only as an imperfect example. Few examples of stereotype plates survive today because they were made of typemetal, which was a material frequently melted down for another purpose after the book was no longer expected to be reprinted. Books of all formats and sizes were stereotyped in the early nineteenth century, and Smith's plates could have been designed to print a slightly larger book than the one corresponding to the plate depicted in figure 1, with proportionally larger text blocks. Similar dimensions obtain to copper plates. The copper plate in figure 2, for example, is 1 millimeter thick with a surface measuring 5.5 × 9 inches. Copper plates also ranged in dimension depending on the size of the page printed. Even fewer examples of copper plates remain extant because copper was a precious metal that was also easily repurposed.

Weight

Several witnesses testified to the heaviness of the plates. Estimates of their weight ranged between forty and sixty pounds. William Smith, Joseph Smith's brother, judged them to weigh around sixty pounds. Martin Harris said that he “hefted the plates many times, and should think they weighed forty or fifty pounds.” Lucy Harris and her daughter similarly described the plates as “very heavy,” with the daughter noting that they “were about as much as she could lift.” Though direct witnesses do not specify how many plates contributed to this load, they observe that together, in a stack, the plates measured somewhere between four and six inches high.Footnote 48

Stereotype and copper plates were heavy when collected together (though not nearly so heavy as gold). Of the boxes of the Library Company's stereotype plates, each weighs thirty-two pounds when filled with forty-four plates, twenty-two on either side of a divider running through the middle (see figure 3). Altogether, the box's plates, stacked one on top of the other, measure approximately four inches, fanning out in their box to a span of six inches. If Smith's plates had originally been stored similarly, their collective thickness would have been more or less the same. So, too, their collective weight. The Library Company's plates weigh between eight and ten ounces each. Since these plates are slightly smaller than the plates Smith said he found, one would want to extrapolate for an estimate of the weight of Smith's plates in a comparable box, expecting that Smith's plates would be heavier and closer to the range of witnesses’ accounts. Copper plates possessed comparable weights and were presumably stored and transported in like ways, with several plates to a box. The copper plate used to print the frontispiece shown in figure 2, for instance, weighs nineteen ounces. Forty plates would total nearly forty-eight pounds, within the range estimated by witnesses.

Figure 3. Interior and exterior views of a typical box for the storage of stereotype plates. Here 22 plates are organized into 11 pairs: the smooth sides are placed back-to-back, with the text sides facing outwards. This box stores some of the plates for James Rush, The Philosophy of the Human Voice (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. [with the cooperation of the Library Company of Philadelphia], 1855. 10 x 8 x 6.5 inches. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Orientation

The described orientation of the characters on the plates provides one of the most evocative clues that Smith had a physical encounter with printing plates. Smith said that the letterforms read from right to left, “running the same as all Hebrew writing in general.”Footnote 49 This orientation is characteristic of printing plates, which displayed text in the reverse of how it appeared printed on the page. Smith's comments invite several questions with relevance for present inquiries. For one, given that he required divine assistance to read the script, how could he have readily discerned its direction? Assuming that Smith was candid in his assertion that he was unable to read the text, he would still have been able to understand a printing plate's orientation because of how its text was justified. Textual justification would be exceptionally clear in the case of stereotype plates. Since a plate is cast as a reversal of the right-reading text on the page, then lines on stereotyped plates were right justified, with indents at the beginnings of paragraphs on the right-hand side and broken edges at the ends of lines at the left, as seen in figure 1. Smith could have discerned the orientation of copper plates in the same manner. If he encountered a long section of engraved text, then the uneven edge at the left would be apparent.

Another question is why Smith and other witnesses, who could read and write, may have not simply recognized the letters as reversed. Possibly, the plates belonged to a book in a language other than English. This was the exact suggestion of Elbert Hubbard, introduced previously, who posited that Smith had shown the witnesses stereotyped plates in Dutch. Hubbard could have been right: By the 1820s, American publishers supplied immigrant populations by stereotyping books in various languages, most frequently Dutch, German, and Spanish. One early example of non-English stereotyping is a Hebrew Bible, published in 1815 in New York (figure 4). The Bible includes pages in the Hebrew language, as well as a preface in Latin, with sections juxtaposing Hebrew, Syriac, and Greek letterforms. If Smith's plates were copper plates, there are further possibilities for what the letterforms could have been, since any script at all—and not just those with prefabricated types—could be engraved on its surface. If the plates were for printing a shorthand manual, for instance, then Smith would have had little hope of recognizing them.

Figure 4. Close-up, page 23 from the Latin preface to The Hebrew Bible, From the Edition of Everardo Van Der Hooght (New York: Whiting & Watson, and stereotyped by D. & G. Bruce, 1815). Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

Characters

A good question to begin an exploration into the characters on Smith's plates is whether they were engraved intaglio (hollowed out of the surface of the plate, as in a copper plate) or cast in relief (sticking out of the surface of the plate, as in a stereotype plate). The accounts differ. In the Wentworth letter, Smith described the plates as “beautifully engraved” by someone with “much skill in the art of engraving.”Footnote 50 These descriptions are consistent with copper plates. Yet, it is not impossible that Smith—who likely had little knowledge of the vocabulary of printing, like the vast majority of Americans at the time—used the word “engraving” nontechnically, to describe metallic letters of any sort, even if those letters were cast in relief.Footnote 51 One description specifically referred to the letters as in relief. This was the 1840 polemical account from John A. Clark, a local pastor in Palmyra. Clark wrote contemptuously in the Episcopal Recorder of how the Mormons’ descriptions of the plates had evolved over the last decade. My emphasis is added: “At first it was a gold Bible—then golden plates engraved—then metallic plates stereotyped or embossed with golden letters.”Footnote 52 Here Clark suggested that, past a point, the plates were described as cast in relief, either stereotyped or embossed. (Like stereotyping, embossing was also a relief process, referring to the stamping of material, especially metal or paper, under high pressure and forcing the material out past its surface.) Clark remained unclear as to whether the idea that the metallic plates contained letters in relief was his own gloss on the Mormons’ discourses on the plates or if Mormons themselves were referring to the characters as cast in relief or even calling them “stereotyped” or “embossed” explicitly. At minimum, Clark's comment indicates that at least one observer described the plates as containing relief, even stereotyped, characters.

Let me mention one especially tantalizing statement about the letterforms before discussing their specific shapes. Orson Pratt, who was close to Joseph Smith but not a physical witness to the plates, announced in two sermons that witnesses had testified to seeing a black residue applied to the letters. In one sermon, recorded in published proceedings, Pratt noted that the letterforms “were stained with a black, hard stain, so as to make the letters more legible and easier to be read.” In a different sermon, published as reminiscences by a congregant, Pratt reportedly described how the engravings were “filled with black cement,” evocative of recessed intaglio characters rather than the raised relief surface of stereotype plates.Footnote 53 In both accounts, the mysterious black substance invites comparison to standard printing ink. If stereotype plates had not been cleaned thoroughly, a patina of ink would have remained on the raised letterforms. An inky residue would have been embedded in the fine grooves of even a cleaned copper plate.

Other continuities are suggested by the specific characters said to appear on the plates themselves. Smith produced several manuscripts containing facsimiles of the characters on the plates, most of which do not survive.Footnote 54 Here, I discuss two of these, starting with the “Anthon transcript” which, though lost, remains an important source because of surviving textual descriptions of its contents. The manuscript was made in Harmony, Pennsylvania, sometime between December 1827 and February 1828 during the interval between when Smith first fled there to begin his translation and when Martin Harris arrived in the area and received the text. From Harmony, Harris set off on a trip around the country, seeking to have the text translated by a number of language specialists, most of whom rejected Harris out of hand. Arriving in New York, he finally secured a meeting with Charles Anthon, a classicist at Columbia University. According to Smith, Anthon said to Harris that the paper contained characters that resembled “Egyptian, Chaldeak [Chaldaic], Assyriac, and Arabac [Arabic]” letters.Footnote 55

More revealing are the written statements made by Anthon in his later personal correspondence. He wrote the first of two letters in 1834 in response to a request from Eber D. Howe, a journalist in the midst of writing an exposé that would be the first published book about Mormonism. In the letter that Howe published, Anthon describes the manuscript in this way:

The paper was in fact a singular scrawl. It consisted of all kinds of crooked characters disposed in columns, and had evidently been prepared by some person who had before him at the time a book containing various alphabets. Greek and Hebrew letters, crosses and flourishes, Roman letters inverted or placed sideways, who[se scribe had] arranged [them] in perpendicular columns, and the whole ended in a rude delineation of a circle divided into various compartments, decked with various strange marks, and evidently copied after the Mexican Calender [sic] given by Humboldt, but copied in such a way as to not betray the source whence it was derived.

The second letter was solicited in 1841 by Thomas Winthrop Coit, an Episcopalian rector in New Rochelle, New York, who had heard about Anthon from area Mormons. A skeptic, Coit had written to Anthon in hopes of setting the record straight. This time Anthon included a few more details about the manuscript and the meeting in his correspondence:

The characters were arranged in columns, like the chinese [sic] mode of writing, and presented the most singular medley that I have ever beheld. Greek, Hebrew and all sorts of letters, more or less distorted, either through unskilfulness or from actual design, were intermingled with sundry delineations of half moons, stars, and other natural objects, and the whole ended in a rude representation of the Mexican zodiac. … Each plate, according to him, was inscribed with unknown characters, and the paper which he had handed me, was, as he assured me, a transcript of one of these pages.Footnote 56

Anthon's remarks suggest several continuities with the letterforms commonly found in early American imprints. First, Anthon noted the variation of scripts, including Roman scripts as well as others in different scripts, mentioning by name Hebrew, Greek, and Syriac. The reference to inverted Roman letters is evocative of stereotypy. If the stereotype plates were for a book in English or any language that used a Roman script, such as Latin, French, or (as Hubbard suggested) Dutch, then the plates would display inverted Roman letters. The other languages mentioned indicate that, perhaps, the stereotype plates included letters from those or similar languages, like the stereotyped Hebrew Bible described previously (figure 4) that incorporated Roman, Hebrew, Greek, and Syriac scripts on the same page.

Second, Anthon's comment that the manuscript contained copious symbols—such as half-moons, stars, other natural objects, crosses, and flourishes—bears comparison with several genres of early American stereotyped books. One is the navigational manual. For instance, the popular Bowditch's Navigator, first stereotyped in 1817, included a symbol key (figure 5) with the meanings of its most frequently used symbols, including half-moons, stars, the sun and moon, and variations on crosses and other designs. In some places in this manual, the characters are arranged in columns, as Anthon observed, though it is far from clear how much to make of that continuity. Anthon remained ambiguous as to whether he understood the characters to be copied out exactly in the shape and order as they appeared on the plate or if they were rearranged. The first letter seems to imply that it was the scribe “who arranged [the characters] in perpendicular columns,” while the second letter's use of the term transcript may be more indicative that the paper was intended as a facsimile.

Figure 5. Close-up, page xiv of Nathaniel Bowditch, The New American Practical Navigator, Fourth Edition and First Stereotype Edition (New York: E.M. Blunt, 1817). Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

Another early American genre that included the symbols enumerated by Anthon was the almanac. While most almanacs were not stereotyped (as annuals, they had no need to be reprinted past the year of publication), almanac publishers would have used stereotypy if they produced on a scale that required tens of thousands of copies or if they wanted to keep plates on hand in the case that they desired to expand the edition. Published in Boston in 1829, the Farmer's Almanack represents one stereotyped almanac that bears the sundry symbols typical of the genre, including zodiac symbols and half-moons and stars, which appear both in-line and organized in columns (figure 6).

Figure 6. Close-up, “May” calendar page, Robert B. Thomas, The Farmer's Almanack, Calculated on a New and Improved Plan, for the Year of Our Lord, 1830 (Boston: Richardson, Lord and Holbrook, and stereotyped by Lyman Thurston & Co., [1829]). Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

One additional source for the appearance of the letterforms is a diminutive manuscript, just 3.25 × 8.125 inches, preserved at the Community of Christ Library in Independence, Missouri. It displays 225 characters arranged in seven horizontal lines (figure 7). The consensus of the Joseph Smith Papers editors is that the manuscript was created by John Whitmer, who probably copied it from an earlier manuscript penned by Smith himself. The earliest date Whitmer could have produced the text was shortly after he met Smith in June 1829.Footnote 57

Figure 7. Manuscript of characters copied from the gold plates. 3.25 x 8.125 inches. Courtesy, Community of Christ Library, Independence, Missouri.

Many of the symbols recorded in the Whitmer document invite comparisons to symbols used in early American books printed from plates. As mentioned previously, copperplate printing was the preferred method for printing letterforms in books that were used with such low frequency that there were no prefabricated types for them. This was the case for the letterforms found, for instance, in manuals of shorthand (stenography); in Masonic books that contained sections in the “royal arch cipher,” the Masons’ code language; and in type specimen books. Stenographic scripts appear especially morphologically similar to the symbols in the Missouri manuscript, particularly in the use of semicircles, lines, dots, and sinuous loops (cf. figures 7 and 8).Footnote 58 It is also worth pointing out that several characters in the manuscript are further reminiscent of the symbols appearing with frequency in all sorts of stereotyped books, including crosses, daggers, parenthetical notations, numbers, and circles or degree symbols. The aim in observing these correspondences is not to determine the exact set of stereotype plates or copper plates that informed, directly or indirectly, the production of this manuscript—which was itself a profoundly mediated document and, moreover, not necessarily intended as a transcription—but to suggest that the manuscript could have been inspired, at some point, by an encounter with printing plates, which commonly bore reversed Roman letterforms, multiple scripts, and various symbols.

Figure 8. A reversed copperplate impression from Jonathan Dodge, A Complete System of Stenography, or, Short-Hand Writing, Containing Ten Copper-plate Engravings (New London, CT: S. Green, 1823). The pages are 8 x 4.75 inches, with slightly smaller platemarks. The page is reversed to reveal the characters as they would have appeared on their original copperplate. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

Imagery

Anthon wrote that the paper ended in a “rude representation of the Mexican zodiac,” which he surmised was “copied after the Mexican Calender [sic] given by Humboldt.” He was referring to the image of an Aztec calendar stone (figure 9), first published in a late-eighteenth-century imprint from Mexico City. The stone became better known to Anglophone audiences after 1814, when Alexander von Humboldt published, in London, its image in his book on Mexico. Though it is tempting to speculate, with Anthon, that Smith copied the picture directly from Humboldt's book, the limits of book circulation at the time cast doubts on that idea. In the 1820s, there were not yet any imprints published in North America that included this image. While Anthon, a scholar in New York, had access to it, probably via London, it is unlikely that an upmarket London or Mexico City imprint would have made its way, by 1827, to rural New York, let alone into the hands of any member of the poor Smith family.

Figure 9. Copperplate engraving of the “Mexican Calendar,” in Antonio De León Y Gama, Descripción histórica y cronológica de las dos piedras (Mexico City: Don F. de Zúñiga y Ontiveros, 1792). Kislak Collection, Library of Congress.

It is more likely that Anthon's comment indicates that the paper contained an image involving circles and other symbols. This remark was consistent with the description of one unnamed observer of the manuscript, referred to only as an “informant” by Orasmus Turner, the mid-nineteenth-century historian of New York: “On it were drawn, rudely and bunglingly, concentric circles, between above and below which were characters, with little resemblance to letters; apparently a miserable imitation of hieroglyphics, the writer may have somewhere seen.”Footnote 59 Comparing Anthon's remarks and those of Turner's informant, it is unclear whether the image was located at the bottom of a page or in the middle of a block of text. In either case, an image that incorporated concentric circles alongside text would not have been unusual in early American stereotyped or copperplate imprints. The stenographic manual described previously, for instance, contained a copperplate diagram of its stenographic system, including concentric circles and other marks (figure 10). If the author of the manuscript copied or recopied it from plates used to print such a book—either directly from physical plates or from his memories thereof—the drawn pictures might have inspired comparisons to Humboldt's calendar.

Figure 10. Copperplate engraving, Jonathan Dodge, A Complete System of Stenography, or, Short-Hand Writing, Containing Ten Copper-plate Engravings (New London, CT: S. Green, 1823). Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

One eyewitness claimed to have viewed images on the metal plates themselves (and not just a paper facsimile, as did Turner's informant and Anthon). This was Joseph Smith, Sr., Smith's father and one of the eight witnesses, who said he recognized Masonic images on the plates. (The senior Smith was a Mason.) The second plate in the box, he attested, was decorated with “representations of all the masonic implements, as used by masons at the present day.”Footnote 60 His testimony appears in a source of unclear reliability, to be sure: He made it in the context of an 1830 interview with the amateur historian Fayette Lapham, who published it forty years after it took place. If the report may be trusted, another option is that the plates were for an illustrated book about Freemasonry, which would also explain Anthon's stars, moons, and crosses, all of which featured in Masonic symbology. Early American imprints about Masonry were often copiously illustrated, either with tipped-in copperplate engravings or with wood engravings stereotyped alongside the text. So, too, the copper plates used for printing banknotes (and counterfeit banknotes) would have included Masonic imagery on them. Yet another avenue is that the senior Smith mistook the symbols of an almanac or navigational manual for Masonic symbols. Again, it is not outside the realm of possibility that the senior Smith imagined all of this. However, because he labeled the illustrations as Masonic in appearance and, moreover, noted that they appeared on the second plate in the box—not only a specific location, but also the typical storage position for an illustrated frontispiece plate—it makes more sense that these detailed observations came out of his experience with an actual set of plates.

Textual Format

A statement made by Smith about the spatial arrangement of text on the Book of Mormon's title page offers another coordinate for the printing-plates hypothesis. In his 1839 history, Smith wrote:

I wish to mention here that the title-page of the Book of Mormon is a literal translation, taken from the very last leaf on the left hand side of the collection or book of plates, which contained the record which has been translated, and not by any means the language of the whole running the same as all Hebrew writing in general [strikeout in the original].Footnote 61

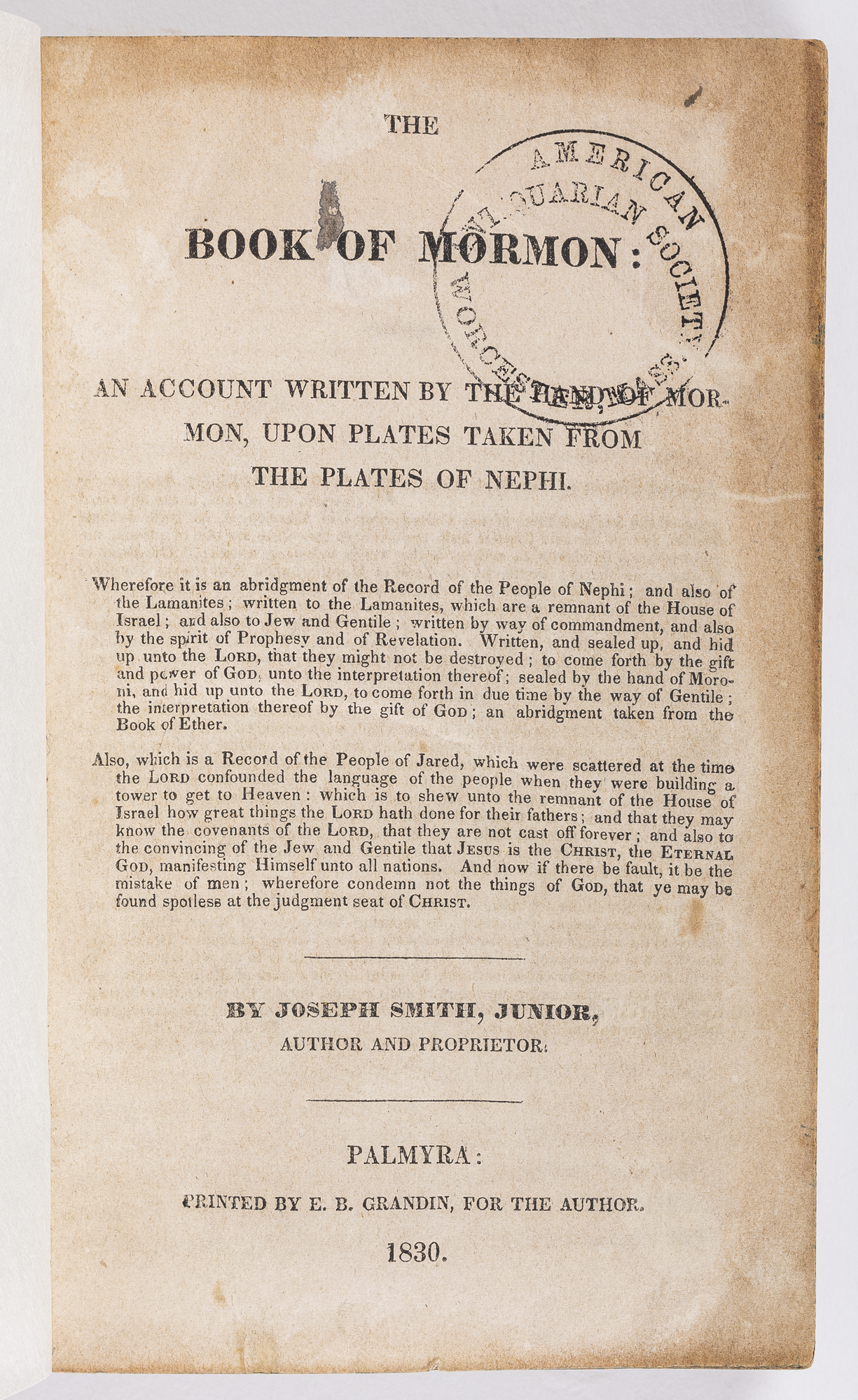

On the face of it, this account is odd and raises more questions. What did Smith mean that the title page was a “literal translation,” and why did he single out the title page in this regard? This inquiry gains focus in light of the possibility that “literal translation” connoted a facsimile of its textual format. In other words, the printed title page's typographical shape corresponded to the same on the plate itself, and Smith regarded the title-page plate to be a part of the ancient sacred work and not merely his own modern paratextual addition. The Book of Mormon's title page is characterized by distinctive formatting elements, all centered down the middle: the title and subtitle, two indented text blocks that describe the contents of the book, authorship lines, and lines with the imprint information of the Palmyra print shop (figure 11). Such a format would have been recognizable as a title page to nineteenth-century readers such as Smith. That Smith, in his inspired translation, may have aimed to reproduce the format and not only the content of the gold plates—and, moreover, that the format of the gold plates corresponded to the format of early American books—contributes to a sense that he had physically encountered real plates out in the world. It further evinces the significance of the material qualities of the plates, here their physical similarities to books, in prompting Smith to write a book of his own.

Figure 11. Title page from the first edition of the Book of Mormon published in Palmyra, New York. Joseph Smith, Jr., The Book of Mormon: An Account Written by the Hand of Mormon, Upon Plates Taken From the Plates of Nephi (Palmyra, NY: Printed by E.B. Grandin, For the Author, 1830). Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

Smith's aside about the location of the title page is worth underlining. It was the “very last leaf on the left hand side of the collection or book of plates.” At first blush, Smith appears inconsistent, for he said the title page was located on the left—indicating that one would read the plates, as in a Western book, from left to right—while at the same time, the plates individually read from right to left, in the manner of languages such as Hebrew. This would be incongruous in virtually all situations except for printing plate storage. In the boxes of stereotype plates, preserved in their original nineteenth-century storage boxes, at the Library Company (figure 3), the plates are organized with the lower page numbers at the left. In the first box, the title page plate may be found as the last plate on the far left side of the box—precisely in the position Smith described. The printing-plates hypothesis comes into view because of the buildup of particulars like these, not owing to any smoking gun. Taken together and triangulated, these sources bring into focus a set of ordinary nineteenth-century printing plates, mitigating the potential unreliability of any one document.

Binding

A final element of the plates is their binding. Smith had said in his Wentworth letter that the plates were “bound together in a volume, as the leaves of a book with three rings running through the whole.”Footnote 62 While this detail does not appear in the “Testimony of the Eight Witnesses,” one of the eight, John Whitmer, later in his life was said to have described the plates as bound this way.Footnote 63 The earliest recorded textual description of this binding seems to be in an 1831 newspaper account, published after Smith no longer had the plates in his possession: A reporter noted that an unnamed preacher visiting Jacksonville, Illinois, described the plates as “connected with rings in the shape of the letter D.”Footnote 64 Granted, this ringed binding does not reflect how printing plates were stored (which was typically loose, in a stack, as depicted previously) so it can be ventured that it was unlikely for Smith to have encountered a stack of printing plates already bound with rings. This detail raises the question, though, regarding whether the many book-like elements of the plates—including their dimensions, orientation, and format of their writing—prompted Smith or other witnesses to expect that the material plates, once taken out of storage and put to use, ought to be bound like a book as well. Perhaps this was a feature Smith appended in his imagination and then repeated to others, or he might have physically modified the physical printing plates by adding rings to them at some point.

How Joseph Smith May Have Encountered Plates

There are any number of contingent settings in which a person and an object could have crossed paths in the world, many of them evanescent and leaving few or no traces in the written record. The existing evidence cannot direct researchers exactly to the circumstances of how Smith made first contact with printing plates, but it does invite speculation. In this section, I wish to examine three plausible scenarios, given what is known of the chronology of early Mormon history and the availability of printing technologies in the area in the 1820s. Recall that Smith reported first seeing the plates in 1823, but he was only able to recover them in 1827. One possibility is that Smith encountered printing plates in 1823 or earlier, feasibly in a local printing shop, inspiring his 1823 vision. A second option is that Smith's familiarity with the Hebrew Bible stimulated his 1823 notion of the plates, and only later, in the interval between 1823 and 1827, did Smith encounter material plates that gave concrete shape to his prior ideation. Third and finally, it could be that Smith really found material plates on the hill, just as he said he did, conceivably glimpsing them in 1823 and retrieving them in 1827. There may well be other possible scenes of encounter beyond these three. The point is to apply a different kind of contextual reading of Smith's circumstances—one attentive to the material circulation and density of printing plates in upstate New York—to demonstrate the plausibility of physical encounter.

In the first scenario, the material encounter came first. Smith might have had an experience with printing plates that predated and shaped his narrative accounts, namely, the vision in 1823 (more on which later) in which an angel appeared at his bedside to tell him about the plates (which Smith glimpsed on the hill the next day), and the even more dramatic episode of 1827 when Smith recovered the plates and took them to his home. In this case, Smith could have encountered printing plates in 1823 or before, exactly where one would expect them to be: in a print shop.

The area surrounding Smith's farm was home to an unusually high concentration of printing establishments for a predominantly rural region in the interior of the country. Printers had set up in nearly every surrounding small town by 1820, in outposts such as Geneva, Batavia, Canandaigua, Buffalo, Auburn, Genesee, and Albion. Among scholars of Mormonism, the most well-known of these is the shop of E. B. Grandin in Palmyra, two miles north of the Smith farm, which published the first edition of the Book of Mormon in 1830. However, Grandin did not print from stereotype plates or copper plates, though he might have owned some as professional curios. Before 1823, Smith would have been most likely to encounter printing plates in Rochester, which would have been accessible to him via the two regular stages per day that made the twenty-three-mile trip between Rochester and Palmyra in the 1820s.Footnote 65

Rochester was a thriving regional printing center. The city's first directory, printed in 1827, listed thirty-one printers employed across six printing offices.Footnote 66 One Everard Peck was the most prominent. Like many printers, Peck operated a retail business out of the front of his shop. He first opened the bookstore and a bindery in 1816 and, two years later, installed presses.Footnote 67 According to his bibliographers, Peck printed at least two books using stereotype technology prior to 1823. The first was the first book ever printed in the city of Rochester, in 1818—a captivity narrative of a sailor lost at sea—printed from stereotype plates Peck had ordered from a New York foundry.Footnote 68 The second, in 1822, was a hymnal printed from plates prepared by a competing New York firm.Footnote 69 The material record indicates that Peck had experience with copper plates as well, for, in the aforementioned 1818 imprint, he tipped in a copperplate map. It is unlikely that Peck would have possessed the special rolling press necessary for printing from copper plates, though almost certainly Peck owned and stored the copper plate itself. He would have ordered the plate probably from New York, arranged for it to be printed there, and then had the plate and a sheaf of impressions shipped to him. Peck needed the copper plate in his possession if he desired to retain the option of extending the edition. (After going to the trouble of having the other pages stereotyped, it is certain that Peck desired to print more copies.)

Enticed, perhaps, by Peck's advertising campaign, Smith could have walked in Peck's front door at any time before or during 1823.Footnote 70 Once there, the printing plates could have been lying on the counter. Perhaps the charismatic Smith talked his way into visiting the back. In either case, how would Smith have reacted to these technological and aesthetic novelties? Stereotypes were covered with carefully molded miniature shapes emerging from their silvery surfaces. Copper plates featured intricate lines grooved into lustrous copper. These objects would have appeared quite marvelous—to borrow an adjective from Mormon scriptures and used frequently by early Mormons—to most Americans outside the book trades at the time, which is to say, to almost everyone. To a curious visionary such as Smith, they would have looked marvelous, indeed.