United States Supreme Court decisions regarding controversial federal statutes or other hot-button political issues are often criticized by those who oppose the ruling, such as the media, political pundits, members of Congress, or the public. The recent decision by the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (597 U.S. 215 [2022]) provides just one example of the type of public response that can occur after a controversial decision. Another potentially damaging reaction to these types of decisions come from legislators who have the power to strip the judiciary of some of their institutional power. For example, Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) said he would introduce a constitutional amendment to establish retention elections for Supreme Court Justices after the tax credit provisions of the Affordable Care Act were upheld in King v. Burwell (575 U.S. 473 [2015]) and same-sex marriage was legalized in Obergefell v. Hodges (576 U.S. 644 [2015]) (e.g., Zezima Reference Zezima2015). Cruz’s attempt to institute electoral accountability in the Supreme Court is a standard example of court-curbing legislation. Court-curbing bills seek to limit judicial power and influence judicial decision-making by proposing changes to the federal judiciary’s composition, jurisdiction, or procedures. Some initiatives only target the Supreme Court, such as the amendment proposed by Senator Cruz, while others target the entire federal judiciary. Examples of proposals include those attempting to alter the composition of the bench, such as instituting a mandatory retirement age for justices and/or federal judges, stripping the judiciary of jurisdiction over certain statutes or policy areas (e.g., cases involving gay marriage or school prayer), or placing restrictions or limitations on the exercise of judicial review (e.g., congressional override procedures). Although there are differences among the purpose of court-curbing bills, each initiative attempts to influence judicial decision-making and/or restrict judicial power and authority.

The interaction between the United States (US) Congress and the Supreme Court that results from the introduction of court-curbing legislation fits within the separation of powers literature, which examines how the various branches of the federal government create and implement public policy. Most studies involving the courts focus on how Congress constrains judicial decision-making (e.g., Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Knight and Martin2001; Hall Reference Hall2014; Sala and Spriggs Reference Sala and Spriggs2004; Segal Reference Segal1997; Segal et al. Reference Segal, Westerland and Lindquist2011; Strother Reference Strother2019) and/or the conditions under which Congress can override Supreme Court decisions (e.g., Blackstone Reference Blackstone2013; Eskridge Reference Eskridge1991; Nelson and Uribe-McGuire Reference Nelson and Uribe-McGuire2017; Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Spriggs and Hansford2014). Consequently, the ability of Congress to influence judicial decision-making with court-curbing legislation is an important but underexplored issue in the Court-Congress relations literature. A crucial research question that has been identified in this area is: How does the introduction of court-curbing bills constrain judicial independence?

Sponsoring court-curbing legislation is largely considered a position-taking endeavor that members of Congress use to express personal and constituent disagreement with Supreme Court decisions (Blackstone and Goelzhauser Reference Blackstone and Goelzhauser2019; Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2018b). Since members of Congress introduce court-curbing bills to help them pursue re-election, the bills are rarely passed into law (e.g., Bell and Scott Reference Bell and Scott2006; Clark Reference Clark2011). Consequently, the Court does not view them as a credible threat to the structure and function of the federal judiciary. Instead, the justices see the occasional court-curbing bill as the position-taking endeavors that they are; however, as more bills are sponsored, they serve as a signal of waning institutional legitimacy (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1992). By attacking the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy, or its role as the branch of government best suited for resolving disputes relating to the interpretation of federal law or the Constitution, court-curbing bills are successful mechanisms for attempting to influence judicial decision-making (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1992).

It is well documented that the Court strives to protect its institutional legitimacy. Political criticism from Congress, the president, the legal community, and the public all limit judicial power in that it impacts if and how decisions are implemented (e.g., Baum Reference Baum2006; Caldeira Reference Caldeira1987; Epstein and Knight Reference Epstein and Knight1998; Hall Reference Hall2014; Ura and Wohlfarth Reference Ura and Wohlfarth2010). The Court is especially sensitive to public criticism because it can motivate additional attacks from Congress and the president that diminish judicial power and discourage implementation (e.g., Casillas et al. Reference Casillas, Enns and Wohlfarth2011; Hall Reference Hall2014; Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira1995, Reference Gibson and Caldeira1998, Reference Gibson and Caldeira2003). Consequently, multiple studies have found that court-curbing legislation results in the justices actively deferring to congressional preferences and striking down fewer federal statutes, especially when there is waning public support for the Court (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Knight and Martin2001; Handberg and Hill Reference Handberg and Hill1980; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2019; Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Curry and Pacelle2014).

Previous work examining how court-curbing legislation constrains judicial decisions assumes that negative constituent reactions to Supreme Court decisions primarily drive the introduction of court-curbing bills (Blackstone and Goelzhauser Reference Blackstone and Goelzhauser2019; Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2018b). However, members of Congress sometimes introduce court-curbing bills to appeal to an issue constituency, such as court-watching interest groups, including Court Watch, Judicial Watch, and the American Constitutional Society, or to “rally constituents and create an electoral benefit” (Clark Reference Clark2011, 84). Just like constituents are assumed to be the motivating force behind court-curbing bill sponsorship, the bills are not always in response to Supreme Court decisions. For example, Clark (Reference Clark2011, 83) recounts an interview with a congressional staffer for a legislator who does not represent a state in the Ninth Circuit but said, “after a decision from the Ninth Circuit declaring the Pledge of Allegiance unconstitutional, we get a lot of calls, telling us to reign in these activist judges.”Footnote 1 After the Ninth Circuit’s decision, seven court-curbing bills were introduced that criticized the Ninth Circuit’s decision and/or urged the Supreme Court to overturn the decision, with one also encouraging the selection of federal judges who are supportive of the Pledge of Allegiance (H.Res 132 sponsored by Congressman Doug Ose [R-CA-3]). Another four were introduced that would strip the federal courts of jurisdiction over cases questioning the Pledge of Allegiance’s constitutionality (usually sponsored as the Pledge Protection Act).

Not only does this example show how members of Congress sponsor court-curbing bills in response to lower federal court decisions, but the lower federal courts also being targeted in these bills demonstrate that legislators are cognizant of how few cases reach the Supreme Court. Consequently, influencing judicial decision-making requires a focus on district and circuit courts, too. This is further supported by the fact that some court-curbing bills do not target the Supreme Court at all. For example, H.R. 73 sponsored by Congressman John Ashbrook (R-OH-17) prohibits lower federal courts from issuing injunctions on federal, state, or local laws that prohibit or regulate abortion. By studies not accounting for court-curbing bills targeting lower federal courts or being sponsored in response to lower court decisions or issue constituencies, the literature is not fully capturing the dynamics of Court-Congress relations after the introduction of court-curbing bills.

In particular, what is missing in the literature is an explanation of why the justices respond to court-curbing bills that are sponsored for reasons other than the public’s discontent with a decision or target the lower courts because neither of these scenarios provides the Court with a direct opportunity to regain its institutional legitimacy. This is because the justices can best regain the Court’s institutional legitimacy when its public support is waning and the bills target the Supreme Court. Yet, the Court has been found to consistently respond to court-curbing bills without knowing the exact motivation behind them or their target (Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Knight and Martin2001; Handberg and Hill Reference Handberg and Hill1980; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2019; Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Curry and Pacelle2014). Given that many court-curbing bills have targets beyond the Supreme Court, what these studies are essentially assuming, and likely capturing, is that the Supreme Court also acts as a guardian of the entire judiciary, not just a protector of its own interests. Consequently, the Court adjusts its decision-making after multiple court-curbing bills are introduced that attack any part of the judiciary to regain the entire federal judiciary’s institutional legitimacy.

If this is true, then the Supreme Court might do more than simply alter its own judicial review decisions but actively correct such decisions of lower courts. This presents a potential missing part of the puzzle: how the Supreme Court dispenses of lower court judicial review decisions following the introduction of court-curbing bills. However, if the Supreme Court behaves in this way, this will not be clearly captured in a count of the number of instances of negative judicial review in a given year. Indeed, this number could change because the Court simply avoids constitutional decisions. The previous literature is telling us a part of the equation: the number of declarations of unconstitutionality decreases. However, this does not tell us the full picture. What is the Court doing instead? The number of laws found unconstitutional could decrease because the Supreme Court is adjusting only its own behavior and avoiding constitutional questions. Alternatively, this decrease could be due to the justices engaging in “guardian” behavior and correcting instances of lower court negative judicial review. The latter possibility seems more in line with what the literature essentially assumes and is likely capturing to an extent in the findings being reported: that the justices are concerned about the institutional legitimacy of the entire federal judiciary, not just the Supreme Court. To know for sure, a better way to explore the effects of court-curbing bills is to look at how the Supreme Court reviews lower court decisions following their introduction.

We seek to fill this gap in the literature. Our analysis contributes to the existing literature by providing a better understanding of judicial behavior in response to congressional attempts to constrain the judiciary with court-curbing proposals. We do so by offering the first case-level analysis of Supreme Court decision-making after the introduction of court-curbing bills at the institutional level. In doing so, we include information about decisions made at the circuit court that were appealed to the Supreme Court.Footnote 2 Additionally, by ending our analysis in 2008, we are able to assess the impact of court curbing on the Supreme Court’s guardian behavior before the widespread use of social media began in early 2009 (Lassen and Brown Reference Lassen and Brown2011).Footnote 3 We find that the behavior of the Supreme Court falls cleanly in line with our guardian theory, with justices not only avoiding negative judicial review after the introduction of court-curbing bills, as previous literature has found but actively correcting instances of such review from circuit courts.

Constraining judicial decision-making with court-curbing legislation

Initial descriptive studies on the effect of court-curbing legislation on judicial behavior sought to determine whether the Supreme Court deferred to congressional preferences – or engaged in sophisticated decision-making – after the bills were introduced to avoid the proposed changes to the structure and function of the federal judiciary (Handberg and Hill Reference Handberg and Hill1980; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1992). The findings indicated that periods of increased court-curbing bill sponsorship coincided with a greater number of judicial decisions that reflected congressional preferences, as evidenced by fewer laws deemed unconstitutional, more cases decided in favor of the federal government, and changes in the voting behavior of the justices. Interestingly, this change in judicial behavior persisted even though court-curbing bills are rarely considered by committees, let alone enacted into law.

Building on these studies, additional research sought to determine why the Court would respond to court-curbing legislation if it was unlikely that the proposed changes would come to fruition. Most scholars concluded that court-curbing bills are signals of congressional or public disagreement with the judiciary, especially Supreme Court decisions, not serious policy proposals seeking to change the structure and function of federal courts (Clark Reference Clark2009; Handberg and Hill Reference Handberg and Hill1980; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2018b; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1992). Furthermore, they argued that increased levels of court-curbing legislation damage the federal judiciary’s institutional legitimacy because they question whether the federal courts are correctly interpreting federal law or the Constitution and if and to what extent its decisions should be implemented. After the sponsorship of multiple court-curbing bills, justices work to regain the judiciary’s reputation immediately by strategically handing down decisions that reflect congressional preferences and (presumably) public opinion (Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Knight and Martin2001; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1992).

Clark’s (Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011) conditional self-restraint model formalizes the idea that the Court responds to increased levels of court-curbing legislation because the bills question the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy, not for seriously threatening the organization or operations of the federal courts. Additionally, higher numbers of these proposals are considered signals of waning public support for the Supreme Court. While building this theory of Court-Congress relations regarding court-curbing legislation, Clark makes assumptions about both legislative and judicial behavior. Members of Congress are still said to use court-curbing legislation as a position-taking endeavor that primarily responds to constituent disagreement with the Supreme Court’s decision-making, although these bills are also introduced when constituents have negative reactions to lower federal court decisions (e.g., the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Newdow [2002]). Clark (Reference Clark2011) also acknowledges that sometimes these bills are not introduced in response to constituents but in an attempt to “rally [them] and create an electoral benefit” or to appeal to court-watching interest groups. When it comes to why the justices respond to court-curbing bills, Clark’s arguments are in accordance with the existing literature: to regain the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy. Specifically, court-curbing bills that are sponsored signal congressional criticism of judicial decisions and waning public support for the Court, both of which diminish the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy. This means there are questions about the role of the Supreme Court in interpreting federal law and the Constitution and encourages the executive branch and other government officials not to implement decisions.

Empirical results support the conditional self-restraint model: justices are most responsive to increases in court-curbing legislation when the bills are reliable signals of waning institutional legitimacy or when they are sponsored by ideological allies in Congress or introduced when the public disagrees with judicial behavior (Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011). During periods when there is little public support for the Court, the justices respond to heightened levels of court-curbing legislation by striking down fewer federal statutes in order to regain its good standing with the public and repair its institutional legitimacy, as both are essential to ensuring decisions are implemented in a timely manner. The Court elicits similar behavior, for the same reasons, when multiple court-curbing bills are proposed by ideological allies in Congress. Since these legislators generally agree with the justices, their court-curbing bills are a credible indication that the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy has diminished (via public and congressional disagreement with judicial behavior), not an effort to criticize the Court and manipulate the ideological content of decisions.

Additional empirical findings support the conclusion that justices respond to increased levels of court-curbing legislation to protect the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy. Marshall et al. (Reference Marshall, Curry and Pacelle2014) find that the Supreme Court is more likely to change the ideological content of constitutional decisions after the introduction of multiple jurisdiction stripping court-curbing bills than in statutory decisions, where maintaining institutional legitimacy is less of a concern. Because legislative power is vested in Congress, a congressional response in statutory decisions would not be considered undermining the federal judiciary, as the decision would be seen as altering legislative intent. At the individual level, Mark and Zilis (Reference Mark and Zilis2019) find that the chief justice and swing justice are more likely to respond to heightened levels of court-curbing bills to protect the Court’s institutional legitimacy by invalidating fewer Acts of Congress. In contrast to these findings and those of Clark (Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011), Segal et al. (Reference Segal, Westerland and Lindquist2011) do not find that higher levels of court-curbing legislation consistently discourage the Court from striking down federal legislation, instead finding this only occurs when the justices are most concerned about institutional legitimacy. Regardless of these findings, the existing literature only addresses how increased amounts of court-curbing legislation influences the ideological content of decisions and whether the Court strikes down an Act of Congress to protect the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy, not whether the Supreme Court changes its approach to reviewing lower court decisions.

The influence of court-curbing bills on constitutional decision-making

The prevailing literature suggests Congress introduces court-curbing bills because of constituent disagreement with Supreme Court decisions and the justices respond when multiple bills have been introduced in an effort to protect the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy as the branch best suited for resolving statutory and constitutional questions and ensuring decisions are implemented (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2019; Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Curry and Pacelle2014; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1992). The Court’s exact response is to defer to legislative preferences by either striking down fewer federal statutes or adjusting the ideological content of decisions (Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2019; Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Curry and Pacelle2014).Footnote 4 While the literature has provided much insight into Court-Congress relations following the introduction of court-curbing legislation, it is not fully capturing how the Court responds, which is partially because the bills are treated as being similar to one another – especially in empirical analyses – when there are important variations that need to be taken into account.

By the literature assuming that Congress primarily introduces court-curbing bills to attack the Court because constituents dislike a recent decision, prior work overlooks how the bills have many potential targets – the Supreme Court, lower courts, or the entire judiciary – and can be sponsored for other reasons. In particular, Clark (Reference Clark2011, 84) discusses how court-curbing bills are also introduced to appeal to an issue constituency, specifically court-watching interest groups, or to “rally constituents” to “create an electoral benefit.” Even when constituents are expressing discontent with judicial decision-making, it is not always about opinions handed down by the Supreme Court. Clark (Reference Clark2011, 83) provides evidence that constituents are often communicating to their members of Congress about circuit court decisions they dislike, which leads to court-curbing bills. This begins to provide insight into why court-curbing bills often target federal courts other than the Supreme Court. It also suggests that members of Congress are aware of how few cases reach the Supreme Court, so it is important to try and influence district and circuit court decision-making.

While more work is needed on the content of court-curbing bills (see Engel Reference Engel2011 as an exception), an initial first step here and to better understanding Court-Congress relations after court-curbing bill sponsorship in general would be to consider the multiple reasons why a member of Congress would introduce the legislation and the court(s) targeted. This is key because it does not appear that there is always an opportunity for the justices to regain the Court’s institutional legitimacy if court-curbing bills get introduced that are not in response to their decisions and do not target them. However, the literature shows that the Court does consistently respond to heightened levels of court-curbing bills regardless of why they were introduced or which court they target (Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Knight and Martin2001; Handberg and Hill Reference Handberg and Hill1980; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2019; Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Curry and Pacelle2014). This suggests that the literature is capturing, but not explicitly testing, the Supreme Court acting as a guardian of the entire federal judiciary and trying to restore not only its own institutional legitimacy but that of the lower courts too.

This is not coming through because empirical work is only testing whether Supreme Court justices actively seek to restore institutional legitimacy following the increased introduction of court-curbing bills by deferring to legislative preferences through declaring fewer federal laws unconstitutional or adjusting the ideological content of decisions, which ignores nuance in the decisions being made by the Court (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2019; Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Curry and Pacelle2014). The literature’s dominant approach of comparing aggregate numbers of instances of negative judicial review year by year cannot fully capture how the Court responds to court-curbing bills. If the Court is concerned about the entire federal judiciary’s institutional legitimacy as the literature suggests, this approach does not tell us when the justices are adjusting their own behavior versus correcting instances of negative judicial review by the lower courts in an effort to shield them, or the judiciary more broadly, from Congressional criticism. Additionally, this fails to answer what the Supreme Court is doing in the absence of finding laws unconstitutional. While changes in the number of laws declared unconstitutional tell us what the Court is not doing, it fails to tell us what the Court is doing. Is the Court simply taking up different cases, or are they not overturning laws because they are instead upholding such laws? One way to capture this dynamic is to focus on how the Supreme Court reviews lower court decisions following the introduction of court-curbing bills. Cases do not arise exogenously. As a result, by the time the Supreme Court hears a case, Congress has already observed what has occurred below. As the lower courts engage in judicial review, Congress may act to try to limit the judiciary in some way. In response to Congress introducing bills that may harm the judiciary’s legitimacy, the Supreme Court, in its position as the head of the judiciary, can correct incidents of lower courts finding laws unconstitutional. As the final arbiter of issues pertaining to federal law and the Constitution, the Supreme Court has the power to review the decisions of lower courts. When the Supreme Court reviews decisions that were made by lower courts, several factors have been shown to influence the final decision. This suggests that a case-level approach is appropriate when thinking about the Supreme Court’s approach to reviewing lower courts’ judicial review decisions.

The question remains as to why the Supreme Court cares about the lower courts’ decisions that find laws unconstitutional and why its review of these cases would be a part of the Supreme Court’s interaction with Congress. First, we suggest that Congress is cognizant of cases going through the lower courts, as is evidenced by the response to the Newdow decision highlighted earlier. Because of this, when the lower courts decide cases that Congress is unhappy with, the Supreme Court is positioned via its review power to “correct” these decisions. Congress can potentially express its dissatisfaction with these decisions in a number of ways between the lower court decisions and the time the Supreme Court decides the case. Following the logic of Clark’s (Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011) conditional self-restraint model, the Court, aware of when the judiciary’s legitimacy is waning, can anticipate that when legitimacy is low, Congress could further attack the judiciary through court-curbing bills, further damaging the Court’s legitimacy. To prevent this, the Supreme Court responds in periods following the introduction of court-curbing bills by overturning more cases from lower courts that find laws unconstitutional. Again, the Newdow case provides further illustration here. The Supreme Court took up the case in 2003. In Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow (542 U.S. 1 [2004]), the Supreme Court decided that Newdow, the petitioner who had won in the Ninth Circuit, lacked standing to bring the case in federal courts because he lacked legal custody of his child. While not directly overturning the case, the Court did nullify the declaration of unconstitutionality from the Ninth Circuit.Footnote 5

This is not to suggest that the Supreme Court is alone in responding to court-curbing bills to protect the federal judiciary. There is some indication, though not systematic evidence, that circuit courts consider Congressional preferences or court-curbing legislation when making decisions (Johnson and Whittington Reference Johnson and Whittington2018; Mark and Zilis Reference Mark and Zilis2018a). Johnson and Whittington (Reference Johnson and Whittington2018) suggest, but do not test, that circuit courts are more likely to uphold federal statutes to avoid being the court that upsets Congress and have the Supreme Court review the decision. Looking more narrowly at responses to court-curbing bills, Mark and Zilis (Reference Mark and Zilis2018a, 334) reported that some, though not all, of the 26 lower federal court judges they interviewed mentioned adjusting opinions because they were concerned about legislative proposals threatening the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy. Footnote 6 However, even if lower courts do engage in the same type of conditional self-restraint as the Supreme Court, there are still reasons that the Supreme Court may also need to take an active role in “correcting” lower court decisions. First, as Segal and Spaeth (Reference Segal and Spaeth2002) note, lower court judges are not as free in their decision-making as Supreme Court justices due to both desires to be elevated (Black and Owens Reference Black and Owens2016, Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Landes and Posner2013), as well as the potential for their decisions being overturned by the Supreme Court (see, e.g., Cross and Tiller Reference Cross and Tiller1998). Second, the Supreme Court has more information in its review of lower court decisions than the judges initially deciding those cases. In the period between the lower court decision and the Supreme Court’s decision, Congress can express its dissatisfaction with these decisions in a number of ways, including introducing court-curbing bills in response.Footnote 7 As a result, in periods following the introduction of court-curbing bills, the Supreme Court will respond not only by finding fewer laws unconstitutional but also by correcting the instances in which lower courts have found laws unconstitutional. In other words, the Supreme Court acts as a guardian of the lower federal courts.

To test this theory, we conduct the first case-level analysis of judicial decision-making after the introduction of court-curbing legislation. We do so by considering all cases reviewing lower federal courts between 1953–2008. Our theory that the Supreme Court acts as a guardian of the reputation of the judiciary rests in the hierarchical nature of the federal judiciary. We follow the logic of Kim (Reference Kim2011), that the Supreme Court, being the top federal court and final arbiter on federal law, is most attuned to heightened levels of legislative attacks since it stands to be most impacted by diminished institutional legitimacy and restricted policymaking power. Moreover, in its role as the final arbiter, it can correct instances of lower court missteps that perhaps lead to the introduction of court-curbing bills.Footnote 8 We simply extend this logic to suggest that the Supreme Court stands as the guardian, or last line of defense, of the federal judiciary in its interactions with Congress. In their role as guardians, the justices are concerned about the institutional legitimacy of the entire federal judiciary, not just that of the Supreme Court. This is rooted in the fact that the bills that are introduced typically affect the entire judiciary, even if the decisions that lead to the bills come only from lower courts. Consequently, it is able to shield the federal judiciary from additional attacks on its institutional legitimacy by deferring to congressional preferences after the introduction of court-curbing legislation increases, not just in its decision of whether to declare laws unconstitutional but in how it reviews lower court decisions. In particular, the Court likely “corrects” instances of negative judicial review on the lower courts when the judiciary’s legitimacy is low. In other words, following the increased sponsorship of court-curbing legislation, the Supreme Court not only changes its own behavior vis-à-vis decisions of constitutionality, but the justices also actively reverse lower court decisions that declare an Act of Congress unconstitutional in an attempt to defer to congressional preferences. This response to heightened levels of court-curbing legislation simultaneously helps the justices restore the federal judiciary’s reputation and signals to the lower federal courts to do so as well in the event this is not already occurring, as suggested by Mark and Zilis (Reference Mark and Zilis2018a). Additionally, it is possible, as Clark (Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011) argues, that the Court responds to increases in these bills conditionally since much of the legislation could be position-taking endeavors and not credible signals of waning judicial legitimacy. Consequently, an increase in court-curbing bills could have more of an impact on the Court’s guardian behavior when, as previously mentioned and suggested by Clark (Reference Clark2009, Reference Clark2011), they are seen as a more credible signal of waning institutional legitimacy by being sponsored when real or perceived public support for the Court is in decline or by an ideologically aligned Congress. These expectations are summarized in the following hypotheses:

H1: The Supreme Court is more likely to engage in guardian behavior by correcting lower court decisions that declare an Act of Congress unconstitutional as the number of court-curbing bills introduced increases.

H2: An increase in the Court’s ideological divergence from Congress decreases the effect of court-curbing bills on the Supreme Court’s guardian behavior.

H3: A decrease in public support for the Court increases the effect of court-curbing bills on the Supreme Court’s guardian behavior.

Data and methods

Judicial review data

To test our hypotheses, we needed measures of when the Supreme Court or circuit courts reviewed an Act of Congress and if the Act was declared constitutional or unconstitutional. To collect this information, we used information from Shepard’s reports on sections of the United States Code.Footnote 9 These reports identify instances in which circuit courts or the Supreme Court consider the constitutionality of each section of the US Code. From each Shepard’s report, we identified every circuit and Supreme Court decision that reviewed that section of the code. If the Shepard’s report indicated that one or more cases found the statute unconstitutional or invalid, we coded this as a declaration of unconstitutionality; if the report indicated one or more cases found the statute constitutional or valid, we coded this as a declaration of constitutionality.Footnote 10 For each declaration of constitutionality or unconstitutionality, we included the circuit court case and its decision and (if applicable) the Supreme Court case and its decision. For sections where both the circuit and subsequent Supreme Court cases appeared in our data set, we matched these two cases into one observation. For all other circuit court cases, we reviewed the subsequent case history. For each case, we identified if the case was appealed to the Supreme Court and, if so, if it was granted certiorari. Since the Supreme Court decision in that instance would not have been marked by the Shepard’s report, we reviewed the decision to see if the Court reviewed the constitutionality of that section of the code. If the Court did not decide on the constitutionality of the section of the code, we coded this as ignoring the question of constitutionality. For cases where there is subsequent circuit court activity that changed the circuit court opinion, we did not code information about the Supreme Court as the case is no longer addressing that decision.Footnote 11

For Supreme Court cases that did not have a match from the Shepard’s reports, we identified the lower court decision that was appealed to the Court.Footnote 12 We then reviewed the affiliated lower court decision for a declaration of constitutionality. If the lower court decision did not address the constitutionality of that section of the code, we coded this as the court ignoring the question of constitutionality.

Our data were then structured such that there was an observation for each review of a section of the US Code. This means the observations were structured code/case, meaning that cases can appear in the data multiple times. We then collapsed our data to create a single observation for each case, we consolidated the multiple observations into a single observation in which the Court can take one of four actions: find all sections of code constitutional, find all sections of code unconstitutional, find some sections constitutional and some unconstitutional, or make no declarations of constitutionality in the case. We go into more detail about how we handle these different approaches when we discuss our methodological approach.

We merged our Shepard’s data with the Supreme Court Database (SCDB). Because we are interested in the Supreme Court’s behavior toward lower federal courts, we removed all cases that were not appealed from a federal court.Footnote 13 Our data contained two simultaneous outcome variables: Law Constitutional and Law Unconstitutional. The two outcomes are dependent: the Court does not decide whether to determine on constitutionality independent of its decision on unconstitutionality. Where a case considered multiple sections of the code, there are four possible outcomes (constitutional, unconstitutional): find all sections of the code constitutional (1,0), find all sections of the code unconstitutional (0,1), find some sections constitutional and some unconstitutional (1,1), or make no declarations of constitutionality in the case (0,0).

Bivariate probit models

The two-variable outcome lends itself to a bivariate probit regression. Bivariate probit models are used for two correlated binary outcome variables, where the decision on one outcome is linked with the decision on the second outcome. The model estimates the outcome variables as coming from a joint probability distribution, allowing the variables to be modeled together. The two models are correlated, represented by the correlation parameter, ρ, which estimates the connection between the two outcomes. If this parameter cannot be distinguished from 0, the two outcomes could be modeled independently. In our models, the correlation parameter was statistically different than 0, indicating that this model is a good fit for the data.

A bivariate probit estimates two sets of coefficients for the two outcome variables. This approach was useful for our purposes since the decision of constitutionality and unconstitutionality are not independent and thus are not well suited to other methods. Our data are structured such that the justices can make a determination of constitutionality on multiple sections of code. They can find all sections constitutional, all sections unconstitutional, find some constitutional and others unconstitutional, or they can make no determination on constitutionality, which is the modal outcome.

Variables of interest

Our primary variable of interest was the number of court-curbing bills introduced in Congress in the year prior to the case, Court-Curbing Billst-1. We used Clark’s (Reference Clark2009) count of court-curbing bills. These data are available through 2008.

Because our hypotheses were conditional in nature, we also included measures of the ideological distance between Congress and the Court, Court-Congress Distance, the Supreme Court’s support, Court Support, and the divergence between the public and the Supreme Court, Court Divergence. These variables were then interacted with our court-curbing measure. To measure Court-Congress Distance, we used Judicial Common Space Scores (Epstein et al. 2007). For each of the Court measures, we calculated the median of the members in the respective institution. We then took the absolute value of both medians subtracted from the Court and used the smaller of the two distances as the distance variable. Our measure of the Court’s support came from the General Social Survey (GSS), Court Support. Following Clark (Reference Clark2009), we used the percentage of people responding they had “hardly any” confidence in the Court in that year. For the years where the question was not asked, we used the average of the year before and after the missing observation. For our divergence measure, we also utilized the measure of Court Divergence that Clark (Reference Clark2009) used as a proxy for support. Because the GSS has only asked the Supreme Court support question regularly since 1973, and the divergence measure has been found to be correlated with Court support (Durr et al. Reference Durr, Martin and Wolbrecht2000), the use of this proxy allowed us to extend our data to 1953. This divergence measure was created by Durr et al. (Reference Durr, Martin and Wolbrecht2000) and utilizes the divergence of both Stimson’s (Reference Stimson1991) public mood measure and the percentage of liberal decisions in salient US Supreme Court cases from their means. The measure is negative when both the Court and the public are either more conservative or liberal than average and positive when one is more liberal and the other more conservative. Thus, as the measure increases, the public and the Court are more divergent, or their ideologies are less similar.

As a control, because court-curbing bills are introduced more often during election years, particularly as position-taking endeavors, we included a measure of whether it was an election year, Election Year. The variable was equal to 1 in a congressional election year and 0 in non-election years.

Because our guardian theory turns on whether the Supreme Court is reviewing and overturning negative instances of judicial review by lower courts, we needed a measure of what was decided at the lower court. We included two variables: Lower Court Constitutional and Lower Court Unconstitutional. Footnote 14 Each of these variables was equal to one if the lower court found at least one section of the code constitutional or unconstitutional, respectively. Guardian behavior occurs when the lower court finds the law unconstitutional and the Supreme Court overturns and finds the law constitutional. Because we were interested in whether this type of behavior changes with the introduction of court-curbing bills, these variables were interacted with our court-curbing measure.

Additionally, because how the Supreme Court reviews lower courts is likely determined by the political makeup of the court being reviewed, we included a measure of the distance between the lower court and the Supreme Court. Our Court Distance measure was the distance between the median JCS scores of the Supreme Court and the court being reviewed.

Results

We see court-curbing bills play a large role in how the Supreme Court reviews lower courts. The results of our analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Results of the Bivariate Probit Regressions

Note: Standard errors in parentheses; *p < .05; Columns 1 and 3 present the results for a declaration of constitutionality and columns 2 and 4 present the results for a declaration of unconstitutionality.

To demonstrate the bivariate probit model’s predictions, Figure 1 shows the predicted probabilities for each of the four possible Supreme Court outcomes for each of the three possible lower court decision types. Because the Court-Curbing Bills variable is interacted with three other variables, the results vary over a number of dimensions. Figure 1 shows the graph for a close Congress and high divergence, both of the indicators that the conditional self-restraint model suggest increase the effectiveness of court-curbing bills. All other predicted probability graphs can be found in the online appendix. What is probably most evident from these graphs is that the lower court’s decision is the strongest prediction of the Supreme Court’s decision and also that court-curbing bills have the strongest effect when the lower court engaged in negative judicial review, finding a law unconstitutional, consistent with our guardian theory.

Figure 1. Predicted Probabilities of Bivariate Probit Regression Over Range of Court-Curbing Bills. For these graphs, the Court Divergence variable is one standard deviation above its mean and the Court-Congress Distance variable is one standard deviation below its mean.

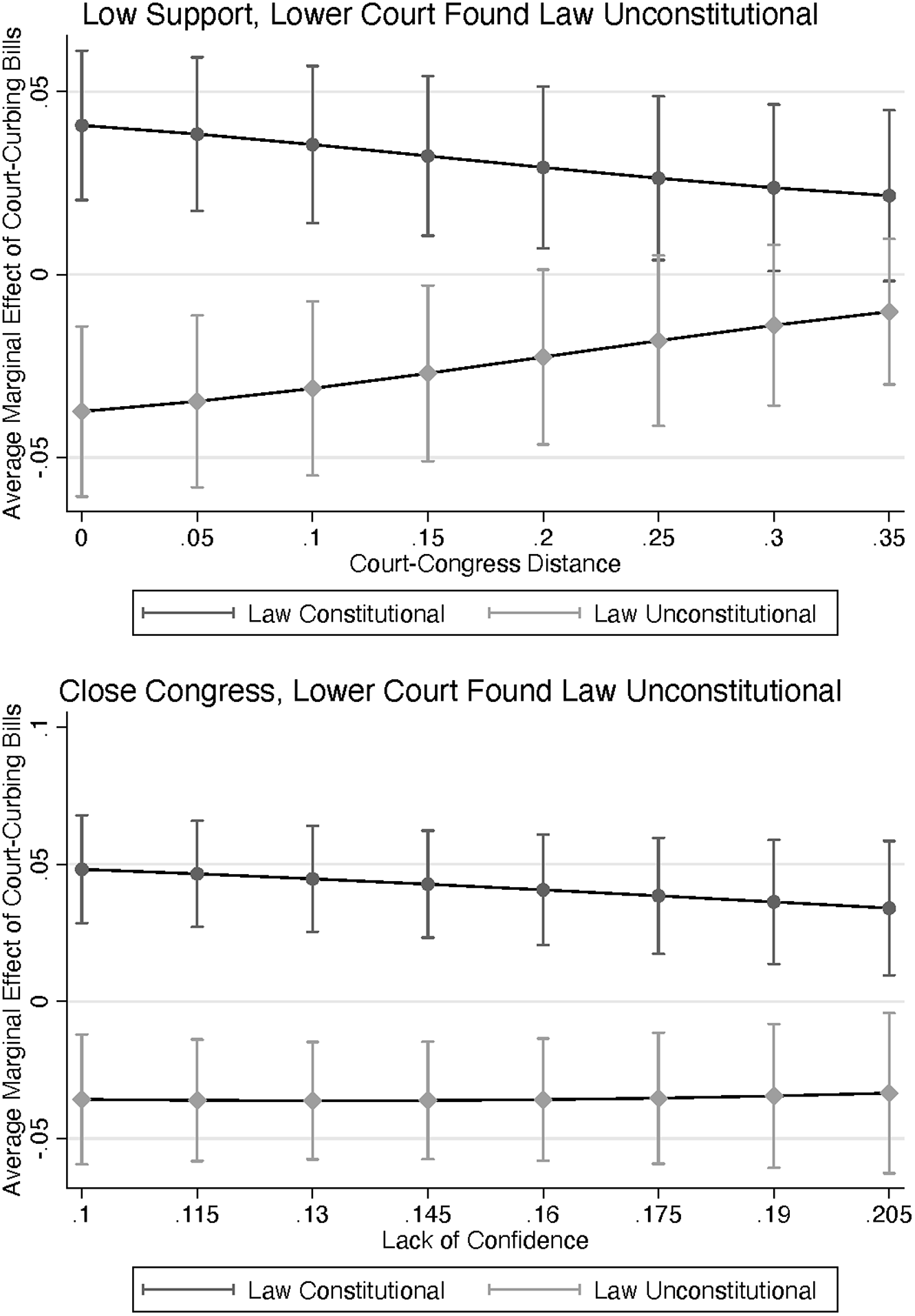

What our results show is that court-curbing bills affect the likelihood of the Supreme Court engaging in this type of guardian behavior, though the effect is not conditioned on either court support or Court-Congress distance. Figure 2 shows the marginal effect of court-curbing bills when the lower court found a law unconstitutional over both the Court-Congress measure and the court support measure.Footnote 15

Figure 2. This figure shows the marginal effect of court-curbing bills on the likelihood of the Supreme Court finding a law constitutional (dark line) or unconstitutional (lighter line) over the range of the Court-Congress distance measure (a) and the GSS measure of the percentage of people who had “hardly any” confidence in the Court (b), where the lower court found a law unconstitutional.

As Figure 2 shows, the effect of court-curbing bills on the likelihood of the Court finding the law constitutional is positive, meaning that the more bills that are introduced in Congress, the more likely the Supreme Court is to overturn the lower court’s decision on constitutionality. Similarly, the likelihood of the Court upholding the lower court finding of unconstitutionality is less likely as more bills are introduced. This is further reflected in the first graph in Figure 1. As the number of court-curbing bills increases, the likelihood of the Court finding a law constitutional where the lower court has found the law unconstitutional becomes a near certainty. This effect is not contingent on either the distance between the Court and Congress or support for the Court. However, consistent with the conditional self-restraint model, when Congress is sufficiently far from the Court, the number of bills introduced does not have a statistically significant effect on the likelihood of the Court engaging in guardian behavior. However, less than 5% of the data are in the range in which this is the case.

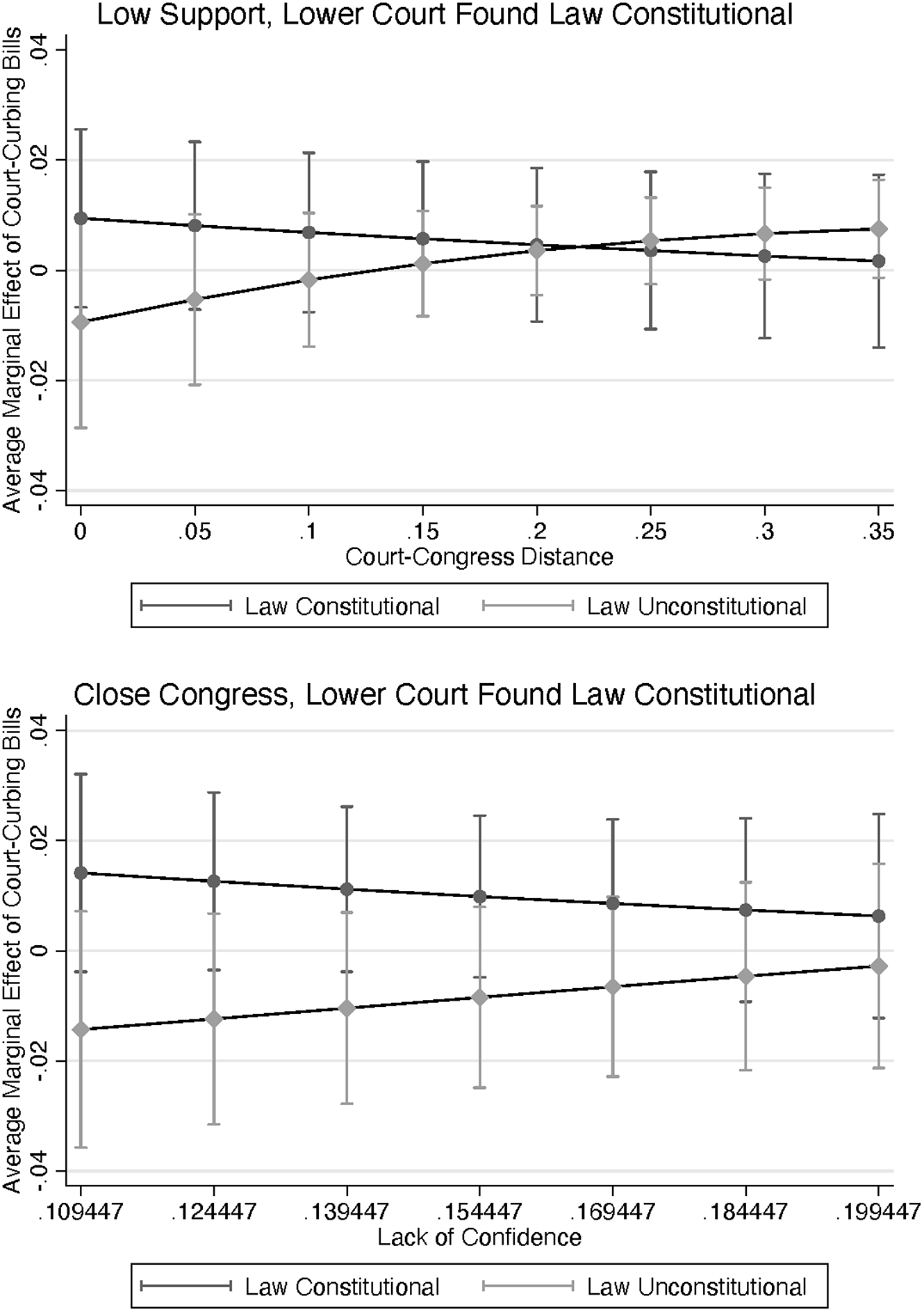

Figure 2 shows the effect on two potential outcomes: the Court finding at least one section of the US Code constitutional and finding no sections unconstitutional and the Court finding at least one section of the code unconstitutional and finding no sections of the code constitutional, or (1,0) and (0,1) on the dependent variables. While the Court can decide some sections are constitutional or unconstitutional or make no decision on constitutionality on either section, (1,1) and (0,0), respectively, we did not find evidence that the likelihood of these outcomes was contingent on the number of court-curbing bills. Additionally, Figure 2 only shows the effect on these two outcomes when the lower court decided a law was unconstitutional, which is when we theorize that the Supreme Court’s guardian behavior would occur. Figure 3 shows the effect when the lower court found a law constitutional over the same variables.

Figure 3. This figure shows the marginal effect of court-curbing bills on the likelihood of the Supreme Court finding a law constitutional (dark line) or unconstitutional (lighter line) over the range of the Court-Congress distance measure (a) and the GSS measure of the percentage of people who had “hardly any” support in the Court (b), where the lower court found a law constitutional.

When the lower court engaged in positive rather than negative judicial review, meaning that they found a law constitutional rather than unconstitutional, we did not find the same effects as when the lower court declares a law unconstitutional. This result helped us to position the guardian theory cleanly within existing research. Previous research has found that when more court-curbing bills are introduced, the Supreme Court declares fewer laws unconstitutional. Under the guardian theory, we propose that this occurs because the Court is actively correcting cases where lower courts have found a law unconstitutional, which we found evidence to support. That the Court does not change its review of cases where the lower court found a law to be constitutional in a predictable way following the introduction of court-curbing bills suggests that previous literature has picked up on what we have termed guardian behavior.Footnote 16

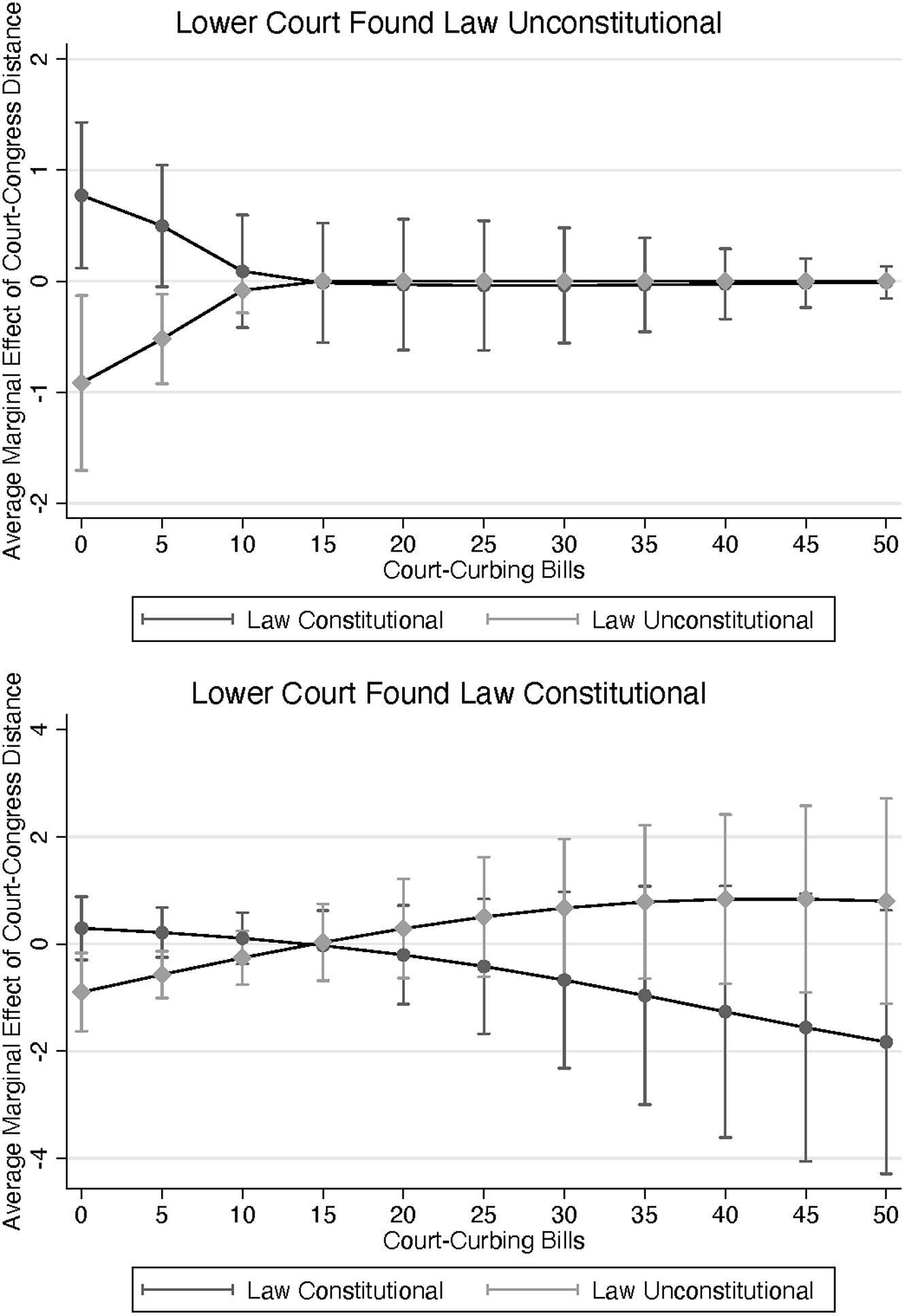

None of the control variables we included in our model are significant at conventional levels of significance. The one exception to this is the measure of Court-Congress distance. Figure 4 shows the results of the marginal effect of court-curbing bills both for when the lower court found a law constitutional and when the lower court found the law unconstitutional. We found that when the number of court-curbing bills is low, the Supreme Court is less likely to find a law unconstitutional the farther it is from Congress when the lower court found a law either constitutional or unconstitutional.Footnote 17 Additionally, when the lower court found the law unconstitutional, the Court is also more likely to find the law constitutional the farther it is from Congress. This leaves open a particularly interesting dynamic between the Court and Congress. Given the myriad of checks available to Congress on the judiciary, perhaps in the absence of court-curbing bills, the Court is responding to some other potential threat from Congress. Future research should do more to differentiate between the different types of checks on the judiciary and how the Court responds to each not only in isolation but as Congress utilizes their checks together.

Figure 4. This figure shows the marginal effect of Court-Congress distance on the likelihood of the Supreme Court finding a law constitutional (dark line) or unconstitutional (lighter line) over the range of the court-curbing bills measure when the lower court found the law unconstitutional (a) and constitutional (b).

Discussion and conclusion

We started by noting that the previous literature has essentially made an assumption that the Court seeks to protect the judiciary as a whole, not necessarily just its own legitimacy, by responding to bills that target any part of the judiciary, without considering how the justices do so. We addressed this by offering the first case-level analysis of the Supreme Court’s decision-making following the introduction of court-curbing bills and defined a possible “guardian” role for the Supreme Court: actively correcting instances on the lower courts where the judges have declared a law unconstitutional. In our analysis, we focused on how the Supreme Court reviews lower courts.

We find strong evidence that the Supreme Court engages in this type of guardian behavior. When the lower courts decide that a law is unconstitutional, the Supreme Court is much more likely to overturn the decision as the number of court-curbing bills introduced in the previous year increases. The effect of court-curbing bills is isolated to the cases where the lower court declared a law unconstitutional. Where the low court instead found a law constitutional or made no decision on constitutionality, we did not find evidence of court-curbing bills influencing the decision on constitutionality at the Supreme Court. This suggests that where previous literature has found evidence of an effect of court-curbing bills, what was found was a decline in the likelihood of upholding lower court decisions where the lower court found a law unconstitutional and instead corrected these cases by finding the law constitutional, what we have called guardian behavior.

We found these results to be helpful for conceptualizing what the mechanism was that was driving changes in the Court’s behavior following the introduction of court-curbing bills. We have found that not only is the Supreme Court finding fewer laws unconstitutional, it is actively correcting instances where lower courts have found laws unconstitutional. There are, however, limitations to what we have found here. First, the court-curbing data we used ended in 2008. While we see this as a positive as it restricts our analysis to an era prior to the widespread use of social media, it is also a limitation in that it does not necessarily translate to this new era. More research needs to be done to determine both whether Congress has changed its use of court-curbing bills in the era of social media and if the Court views these bills differently. With this, our data also exclude the highly polarized era of politics seen in more recent years. While we have tried our best to control for this through robustness checks using a polarization measure, given the higher level of polarization in recent years, we cannot control for anything not in our data. Future research should be particularly attentive to the role of polarization in this relationship.

Future research should also explore the questions we began to pose in this paper and, more specifically, the individual bills themselves. Because not every bill equally targets the judiciary or targets all parts of the judiciary, it is possible the courts only respond accordingly. Future research should look both at the content of these bills as well as the level of threat each bill presents. Additionally, our results have potential implications about why the Supreme Court brings up certain cases over others. Looking at the certiorari decision following the introduction of court-curbing bills would be a natural extension to this approach.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2023.22.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank panels from MPSA and SPSA, as well as the Student Faculty Workshop at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for helpful feedback on early drafts of this paper.

Data availability statement

All replication materials can be found in the Journal of Law and Courts’s Dataverse archive.