Introduction

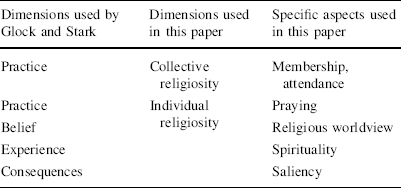

‘Suppose someone claims to be moved by a deep sense of spirituality. Is this faith likely to compel caring activities if it is held apart from involvement in any religious community?’ (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1991, p. 154). The more people withdraw from religious community life, the more urgent this question becomes for the investigation of the role of religiosity for volunteering behaviour. Wuthnow makes a distinction between ‘collective’ and ‘individual’ aspects of religiosity, using the terms ‘community’ and ‘conviction’ (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1991, p. 154). In 1968 Glock and Stark showed that religiosity is a multidimensional phenomenon, distinguishing between practice, beliefs, experiences, consequences and knowledge (Stark and Glock Reference Stark and Glock1968). Practice refers to collective aspects of religiosity (religious attendance, religious affiliation) as well as individual ones (praying, reading in the Bible). Belief, experience, consequences and knowledge are considered individual religious characteristics, predominantly occurring in the private and informal sphere (Davie Reference Davie2000, p. 7; Reitsma et al. Reference Reitsma, Scheepers and Te Grotenhuis2006a).

Research has shown that particular aspects of religiosity which are observable in the public and formal sphere of denominations, such as religious affiliation and attendance, are positively related to formal volunteering (Wilson and Janoski Reference Wilson and Janoski1995; Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997a; Becker and Dhingra Reference Becker and Dhingra2001; Lam Reference Lam2002; Cnaan Reference Cnaan2002, pp. 211–233; Ruiter and De Graaf Reference Ruiter and de Graaf2006). Although the levels of collective religiosity have declined in the Netherlands, no serious drop in volunteering has occurred (Bekkers and De Graaf Reference Bekkers and de Graaf2002; Van Ingen Reference Van Ingen2008; Van Tienen et al. Reference Van Tienen, Reitsma, Scheepers and Schilderman2009). One reason for this might be that it is the individual rather than the collective aspects of religiosity that stimulate volunteering behaviour.

Individual aspects of religiosity have been investigated in a number of previous studies, but most of them included only one or two aspects of individual religiosity (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997b; Becker and Dhingra Reference Becker and Dhingra2001; Lam Reference Lam2006). Some of these studies which included individual aspects of religiosity have revealed the importance of the collective aspects of religiosity, downplaying the idea that individual aspects of religiosity are relevant to formal volunteering (Wilson and Janoski Reference Wilson and Janoski1995; Park and Smith Reference Park and Smith2000; Becker and Dhingra Reference Becker and Dhingra2001), although an intrinsic religious motivation seems to be related to formal religious volunteering (Cnaan et al. Reference Cnaan, Kasternakis and Wineburg1993). Other studies have shown that, for example, private Bible reading and praying are related to volunteering behaviour, giving support to the idea that individual aspects of religiosity do play a role, at least with regard to formal volunteering (Lam Reference Lam2002; Loveland et al. Reference Loveland, Sikkink, Meyers and Radcliff2005). However, none of these studies has simultaneously included a variety of indicators of individual religiosity, such as beliefs, spirituality and salience of religion. Recently, Reitsma et al. (Reference Reitsma, Scheepers and Te Grotenhuis2006b) and Bekkers and Schuyt (Reference Bekkers and Schuyt2008) have focused more extensively on the role of individual religious characteristics for formal volunteering. Their results have shown that individual as well as collective religious aspects are related to religious and non-religious formal volunteering.

Our contribution to studies on the relationship between religiosity and volunteering behaviour is twofold. First, we investigated more aspects of religiosity: our data include different indicators for individual as well as collective religious characteristics. This makes it possible to test more rigorously which particular aspects of religion are important for volunteering behaviour. Our first research question is: To what extent are individual religious characteristics, in addition to collective religious characteristics, related to formal volunteering in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 21st century?

Second, in addition to volunteering within institutions, we focus on the provision of help to individuals as an example of informal volunteering behaviour outside of civic associations. Although formal volunteering is of a more public nature and is related to associations or institutions, and informal volunteering behaviour is more spontaneous and displayed in private settings, the latter should undoubtedly be considered an aspect of volunteering behaviour in general (Wilson Reference Wilson2000, p. 216). In previous research the distinction between formal and informal volunteering has also been made (Cnaan and Amforell Reference Cnaan and Amforell1994; Cnaan et al. Reference Cnaan, Handy and Wadsworth1996; Meijs et al. Reference Meijs, Handy, Cnaan, Brudney, Ascoli, Ranade, Hustinx, Weber, Weiss, Dekker and Halman2003).

Religion might also function as a source of informal volunteering. There are a number of studies on the role of religion for informal aspects of volunteering behaviour, such as helping friends, family and neighbours, but research is scarce and the results are ambivalent (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997b; Scheepers and Janssen Reference Scheepers and Janssen2003). We build on this research, answering a second research question: To what extent are individual religious characteristics, in addition to collective religious characteristics, related to informal volunteering in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 21st century?

Theory and Hypotheses

Collective Versus Individual Religiosity

When Stark and Glock (Reference Stark and Glock1968) gave new impetus to the sociological study of religion, they started by defining what religious commitment means. They proposed that the different ways in which religiosity ought to be manifested, can be divided into different dimensions: belief, practice, experience, consequences and knowledge. Other authors distinguished two, more general aspects of religiosity in terms of networks and norms (Durkheim 1951 [Reference Durkheim1897]; Stark and Bainbridge Reference Stark and Bainbridge1996) or community and conviction (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1991, p. 154).

Integrating these perspectives, we focused on the dimensions as distinguished by Stark and Glock (Reference Stark and Glock1968) and divided them into collective and individual aspects of religiosity. Collective aspects of religiosity (e.g. religious affiliation and attendance) necessarily manifest themselves in religious communities (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1991, p. 154), networks (Durkheim 1951 [Reference Durkheim1897]). Individual aspects of religiosity (e.g. private prayer, beliefs, experiences and consequencesFootnote 1) do not necessarily involve a community or network, but are merely a matter of conviction (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1991, p. 154) or norms (Durkheim 1951 [Reference Durkheim1897]).

Collective aspects are measured by denomination membership and religious attendance. Individual aspects are measured by praying, a religious worldview, spirituality and saliency. Denomination membership, religious attendance and praying are examples of Glock and Stark’s dimension ‘practice’. A religious worldview is related to Glock and Stark’s dimension ‘belief’ and refers to classical religious Christian and Jewish beliefs about, for example, the existence of God, and life after death. Saliency is used to measure what Glock and Stark call ‘religious consequences’ and refers to the extent to which people use edicts of their religion for other aspects of their daily lives.

Spirituality refers to Glock and Stark’s dimension ‘religious experience’. We defined spirituality as a religious dimension, a broad, personal, extra-institutional religious orientation. However, in psychological research, it is often defined as a concept distinct from religion (or sometimes religion is even regarded as a dimension of spirituality). Although we differ from the opinion expressed in this literature when considering spirituality an aspect of religion, our definition of spirituality is close to the definition commonly used in studies based on this psychological conceptualization (Hood et al. 2004 [Reference Hood, Hill and Spilka1975], pp. 8–11; 33–36). Table 1 gives an overview of how the different classifications are related.

Table 1 Aspects of religiosity

|

Dimensions used by Glock and Stark |

Dimensions used in this paper |

Specific aspects used in this paper |

|---|---|---|

|

Practice |

Collective religiosity |

Membership, attendance |

|

Practice |

Individual religiosity |

Praying |

|

Belief |

Religious worldview |

|

|

Experience |

Spirituality |

|

|

Consequences |

Saliency |

Individual Religiosity

The past few decades saw a strong decline in religious participation in the Netherlands (Bernts et al. Reference Bernts, Dekker and De Hart2007). Previous studies have shown that this decline in religious participation has not led to an ongoing decline in volunteering (Van Ingen Reference Van Ingen2008; Van Tienen et al. Reference Van Tienen, Reitsma, Scheepers and Schilderman2009). One of the reasons might be that not all those who stopped participating in religious communities became non-religious, i.e. they might still have religious beliefs and/or experiences, or have religiosity guiding other aspects of their lives. This would, however, falsify Durkheim’s version of integration theory to a certain extent, because his core proposition is that network integration is crucial for norm conformity, also in terms of reciprocals.

Durkheim provides us with a network perspective to explain norm conformity, supposing that network integration is crucial for people to follow group norms. However, from a normative perspective it can be argued that religious people who do not participate in religious networks might still adhere to religious values as guidelines for their behaviour (Batson et al. Reference Batson, Schoenrade, Pych and Argyle1985; Cnaan Reference Cnaan2002, pp. 211–233). Within all major religions, followers are ‘encouraged to be compassionate’ (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1991, pp. 121–156; Batson et al. Reference Batson, Schoenrade and Ventis1993, pp. 331–338). Adhering to religious norms while not being part of a religious community excludes social rewards as a possible motivation. However, the motivation here might be that people prefer these religious values to other, non-religious values. People are influenced directly or indirectly by religious values or use them as guiding principles throughout their lives. Therefore, we hypothesize that aspects of individual religiosity increase the likelihood of formal and informal volunteering (H1a).

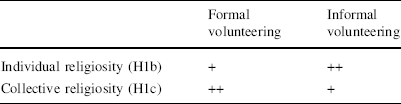

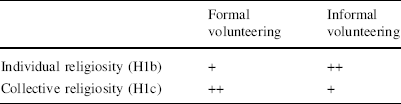

However, because of differences in characteristics between formal and informal volunteering, we expect relationships between collective and individual religiosity on the one hand and formal and informal volunteering on the other to differ in strength. Individual religiosity, as we describe it, entails aspects of religiosity such as private praying, religious beliefs and spirituality, which are commonly not shown to a religious community (Hood et al. 2004 [Reference Hood, Hill and Spilka1975], p. 11). Therefore, social rewards might not function as a motivation here. However, another reason for volunteering can be the wish to help others. Generally, helping or informal volunteering is more direct than formal volunteering, because in most cases help is provided directly by the one who is being asked to help and no association is needed (Pearce and Amato Reference Pearce and Amato1980). Taking someone to see a doctor (informal volunteering) solves someone’s problem more directly than being a member of the local football club’s board (formal volunteering). We expected that directness would be particularly important to individual religious people, as individual religiosity is characterized by people preferring religious values as guiding principles in daily life to other, non-religious values. If a value is to be helpful and caring, then it may be assumed that it is important to the person in question that what he or she does is indeed helpful. We assume that the more direct voluntary behaviour is, the stronger someone perceives that what he or she does is indeed helpful. An additional reason for a stronger relationship between individual religiosity and informal volunteering than between individual religiosity and formal volunteering might be people’s general scepticism towards institutions. This might explain their staying out of church as well as their staying away from associational volunteering (Farnsley Reference Farnsley2006). We therefore expected individual religiosity to be more strongly related to informal volunteering than to formal volunteering (H1b, Table 2).

Table 2 Differential hypotheses

|

Formal volunteering |

Informal volunteering |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Individual religiosity (H1b) |

+ |

++ |

|

Collective religiosity (H1c) |

++ |

+ |

Collective Religiosity

When investigating influences of individual religious characteristics, it is highly important to control for collective religious characteristics, as previous research has shown that religious attendance in particular is related to volunteering behaviour (Wilson and Janoski Reference Wilson and Janoski1995; Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997a; Becker and Dhingra Reference Becker and Dhingra2001; Lam Reference Lam2002; Cnaan Reference Cnaan2002, pp. 211–233; Ruiter and De Graaf Reference Ruiter and de Graaf2006). It has been shown that the relationship between religiosity and volunteering is mediated by denominational involvement, and is not a direct result of prevailing religious norms and teachings. Crucial are social networks that provide contacts and enhance norm conformity within the group (Bekkers Reference Bekkers2000; Cnaan Reference Cnaan2002, pp. 211–233).

We expected people’s religious attendance to directly reflect their religious integration. However, we will also consider other aspects of collective religiosity, such as denomination membership, denominational differences, religious upbringing and denomination membership of parents and partners. Previous research (Wilson Reference Wilson2000) mentioned that it might not only be an individual’s own integration, but that of other persons in his or her household as well, that might influence a person’s religious attitudes and behaviour. Religiosity of the partner and parents are therefore regarded as indicators of a person’s religious integration as well. Furthermore, alongside contemporary family characteristics, we expected family characteristics during the socialization period to reflect the extent of religious integration.

Because of differences in characteristics between formal and informal volunteering, we expected that the role of collective religiosity would be different for these two types of volunteering. Formal volunteering is more visible than informal volunteering because it commonly takes place in the public sphere, within associations, where it is known which persons occupy certain positions. Informal volunteering, on the other hand, takes place in the private sphere and is therefore less visible to other members of the community. Batson et al. (Reference Batson, Schoenrade and Ventis1993, pp. 331–364) argued that visibility of volunteering behaviour is important when the volunteer aims for social rewards. Contrary to aspects of individual religiosity, aspects of collective religiosity are characterized by their social character. Therefore it is more likely that social rewards function as a motivation to volunteer for those who have been integrated into a religious community. When social rewards are the motivation to volunteer, formal volunteering is more likely than informal volunteering, because it is more visible and therefore more likely to be recognized by other people. Therefore, our expectation was that collective religiosity is related more strongly to formal volunteering than to informal volunteering (H1c, Table 2).

The Relationship Between Effects of Collective and Individual Aspects of Religiosity

We assumed that collective religiosity and individual religiosity independently increase the likelihood of volunteering. However, in practice, these aspects of religiosity might reinforce each other. Integration into a religious community means being integrated into a group that rewards volunteering behaviour and, moreover, provides connections to make it easier to become involved in voluntary work. However, these circumstances will be more important to those who adhere to intrinsic positive values with regard to volunteering behaviour. We maintain that collective religiosity is more important when it goes hand in hand with aspects of individual religiosity. So far, no extensive investigation has been conducted into the effect of ‘believing with belonging’. Consequently, we have no specific predictions about which particular aspect of individual religiosity might reinforce the effect of religious integration on volunteering behaviour. We therefore explored the field by investigating different combinations of religious attendance and aspects of individual religiosity. This led us to the hypothesis that the stronger a person’s individual religiosity is, the more religious attendance increases the likelihood of formal and informal volunteering (H2).

Spill-Over Effect of Collective Religiosity

Putnam mentions ‘bridging and bonding social capital’. With bonding social capital he refers to involvement in associations of people who are already closely connected. However, ‘bridging social capital’ in particular is assumed to have societal benefits (Putnam Reference Putnam2002, pp. 11–12). Building on previous research in which a relationship between religious involvement and aspects of volunteering was found, the question can be raised as to whether this volunteering is only ‘bonding’, in other words, whether religiosity is only related to religious volunteering, or also ‘spills over’ into secular volunteering. Some previous research has shown that denomination members are more likely than non-members to volunteer within secular associations as well (Reitsma et al. Reference Reitsma, Scheepers and Te Grotenhuis2006b; Ruiter and De Graaf Reference Ruiter and de Graaf2006; Bekkers and Schuyt Reference Bekkers and Schuyt2008). Others found that religious involvement does not only increase the likelihood of religious volunteering, but of secular volunteering as well, implying that religious people often combine religious and secular volunteering (De Hart and Dekker Reference De Hart, Dekker and Roßteutscher2005).

Control Variables (Non-Religious)

Previous research has shown a number of other variables influencing the likelihood of formal and informal volunteering. For example, gender has been shown to play a role with regard to different forms of volunteering behaviour. Women are generally more inclined to informal volunteering (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997b) than to formal volunteering (Bekkers and De Graaf Reference Bekkers and de Graaf2002; Reitsma et al. Reference Reitsma, Scheepers and Te Grotenhuis2006b). The possible explanations for this have not yet been fully investigated.

People’s levels of education appear to be strongly and positively related to formal and informal volunteering, except that low-educated people are more likely to help their neighbours (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997b; Gesthuizen et al. Reference Gesthuizen, Van der Meer and Scheepers2008). The positive relationship between level of education and aspects of volunteering behaviour supports the theory that education broadens people’s orientation towards their surroundings.

There are other characteristics that provide people with resources or that function as constraints that influence the likelihood of their volunteering. In previous research it has been found that a wide range of determinants of volunteering behaviour is positively related to physical and mental health (Halpern Reference Halpern2005, pp. 73–112).

Having a paid job can be either a resource or a restriction. It can be argued that those with a paid job have been more strongly integrated into society and have better skills than those without a paid job and are therefore more able to do volunteering work (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997b; Putnam Reference Putnam2000, pp. 189–203). On the other hand, people can spend their time only on one thing at a time, and from this perspective, having a paid job is a constraint and the relationship might turn out to be negative.

With regard to having children, similarly opposing expectations may be formulated: childcare can constitute a time constraint as well as a motivation as children can be expected to increase the parents’ integration in their social network. It has been found that the likelihood of formal and informal volunteering changes with age (Putnam Reference Putnam2000, pp. 247–249). Finally, the number of times people moved house and the level of urbanization of their place of residence both restrict volunteering in the sense that frequent relocations and living in an urbanized area make strong integration in the residential context more difficult (Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995, pp. 452–455; Putnam Reference Putnam2000, pp. 204–215).

Data and Analyses

We tested our hypotheses using data derived from the Religion in Dutch Society survey (SOCON), which was conducted in late 2005 and early 2006 (Religion in Dutch Society, 2005–2006). This survey is part of a research programme which was initiated in 1979 under the direction of Radboud University Nijmegen and is held every 5 years.

To obtain a nationally representative sample, a two-stage random sampling method was used. First, a random sample was drawn from the address database of the Dutch postal company TPG. Next, from these households, household members were selected who had most recently celebrated their birthday. Data were collected by face-to-face interviews with people aged 18–70, and by additional questionnaires. The response rate was 55.7%. This resulted in a dataset (n = 1,212) which appeared to be representative in terms of urbanization and region. The distribution of age in the sample, however, was not representative: young people (aged 18–29) were underrepresented, whereas elderly people (aged 60–70) were overrepresented. The reason for this might be the two-stage sampling method that increases the likelihood of people living in relatively small households to be selected, because young people (aged 18–29) live on average in larger households compared to elderly people. Therefore, a second round of data collection was initiated, focusing particularly on young people. This round was conducted in the period March–April 2006 (Religion in Dutch Society, 2005–2006).

Dependent Variables (Volunteering Behaviour)

Formal volunteering was measured using the question: ‘Do you do voluntary work for an association? If yes, how many hours a month?’ Because of the skewness of the distribution we recoded it into a binomial variable, distinguishing between those who do and those who do not volunteer.Footnote 2 Although we are aware of the insensitivity of this binomial distinction, the severity of the skewness would make results based on the use of the more precise measure of hours of volunteering less reliable.Footnote 3 Because of the use of this binomial variable, our results must be interpreted with care, as being relevant only with regard to the likelihood to volunteer, be it regularly or incidental (Musick and Wilson Reference Musick and Wilson2000, pp. 26–28). Although this does not provide us with the most extensive information, we regard this distinction as relevant, merely because the larger part of the people does not volunteer at all.

Informal volunteering was measured using the question: ‘I will ask you a number of questions with regard to people providing help to others, particularly help with practical household things, looking after children, shopping, lending someone something, giving advice or talking with someone who needs cheering up’. People have been asked how often they provide one of these kinds of help to family, friends, colleagues, neighbours and other people. The answer categories were: ‘Every day, more than once a week, once a week, more than once a month, once a month, less often, never’ (reversely coded from 1 to 7). For the items together, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77. The scale scores are the respondents’ mean scores on the five items.

Independent Variables (Individual Religiosity)

To measure aspects of individual religiosity, we used scales described extensively in Felling et al. (Reference Felling, Peters and Schreuder1991, pp. 7–39). They developed these scales to investigate religion in the Netherlands. The scales ‘religious worldview’, ‘spirituality’ and ‘saliency’ represent the religious dimensions mentioned by Stark and Glock (Reference Stark and Glock1968): religious beliefs, religious experiences and consequences of religion.

The first scale, called religious worldview, consisted of 10 items that represent a traditional religious interpretation of the existence of a higher reality, the meaning of life, suffering, death, and good and evil. Examples of the items were: (1) There is a God who concerns himself with every individual personally. (2) There is a God who wants to be our God. (3) Life only has meaning for me because of the existence of God. (4) Life has meaning because there will be something after death. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.94. The answer categories ranged from 1 ‘strongly convinced’ to 5 ‘not convinced at all’ or 6 ‘never thought about it’. We recoded the answer categories in such a way that a higher score indicated a stronger religious interpretation. The scale score of a respondent is the mean score on all items.

The spirituality scale involved answers to six different questions: (1) I believe miracles can happen. (2) I believe life depends on some spiritual power. (3) I sometimes feel a spiritual relationship with other people which I cannot explain. (4) I sometimes feel like my life is led by a spiritual power that is stronger than us human beings. (5) I have a spiritual relationship with people around me. (6) I think that most things that are called miracles are just coincidences (reversely coded). Cronbach’s alpha for this six-item scale was 0.82. The answer categories and scale construction for ‘spirituality’ were similar to those for ‘religious worldview’.

The saliency scale consisted of three questions: (1) My worldview plays an important role in my daily life. (2) My worldview influences to a large extent every important decision I make. (3) My worldview strongly influences my political views. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.82.Footnote 4 Answer categories and scale construction were the same as for the scale ‘religious worldview’.

Praying was measured by a single question: ‘Do you yourself pray now and then?’, the four answer categories being: ‘yes often’, ‘yes regularly’, ‘sometimes’ and ‘never’. We recoded this into a variable ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Because of the possibility of collinearity, we checked collinearity statisticsFootnote 5 and came to the conclusion that the analyses could be performed including all indicators of individual religiosity.

Independent Variables (Collective Religiosity)

The question on denomination membership was: ‘Do you think of yourself as a member of a church or religious community? If yes, which one?’ Besides non-membership, the following denominations were distinguished: Roman Catholic, mainstream Protestant (Protestant Church in the Netherlands, except the orthodox wing called Reformed Union), Orthodox Protestant (Reformed Union within Protestant Church and all reformed churches outside the Protestant Church), and other religious (including Muslims). Although in 2006 about 6% of the Dutch population was Muslim (statline.cbs.nl), we could not investigate Muslims separately because the share of Muslims in our data is below two percent. Moreover, we expect that this is not a represented share of the Muslim population in the Netherlands, mainly because this survey was held in Dutch language which excludes a significant part of the Muslim population from survey participation.

To measure previous denomination membership, the respondents were asked whether they previously used to think of themselves as members of a church or religious community, and if yes, which one. The answer categories were the same as for current membership. We combined current and previous denomination membership into a new variable with the categories ‘Non-religious’, ‘Catholic’, ‘mainstream Protestant’, ‘orthodox Protestant’, ‘other religious group or denomination’, ‘apostates’ and ‘changed denomination or converted’.

Another measurement of collective religiosity is religious attendance, which was measured by the following question: ‘Do you visit church meetings or meetings of a religious community now and then?’ The answer categories were: ‘yes, about once a week’; ‘yes, about once a month’; ‘yes, once or a few times a year’; ‘seldom or never’.

Another aspect of collective religiosity is denomination membership of the partner. The available data also included information on whether the respondents had a partner and whether the partner could be considered to belong to a religious denomination. We therefore included a variable for whether or not respondents had a religious partner. As not all respondents had partners, we also included a variable for having a partner.

Respondents were also asked whether their fathers and mothers were denomination members. We combined the answers to this question into denomination membership of parents, the answer categories being: ‘neither parent is a church member’, ‘one of the parents is a church member’, and ‘both parents are church members’.

The question on religious upbringing was: ‘Were you raised religiously?’. The answer categories were: ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘somewhat’. We decided to include those who answered they were raised ‘somewhat religiously’ in the category ‘raised religiously’.

Control Variables

Denomination members were asked: ‘Are you an active member of church-related groups or associations?’. We constructed a variable for active membership of a church-related association, distinguishing between those who were active members of a church-related group or association and those who were not. We included this variable in a final model of volunteering to see if there were spill-over effects of denomination membership and religious attendance on volunteering after controlling for volunteering in their own religious community.

Other control variables were: gender, level of education, poor health, having a paid job, having children, age, number of times people moved and level of urbanization of the place of residence.

Analyses

We used logistic and linear regression models for formal and informal volunteering respectively. We introduced our independent variables stepwise, in different models. The first model contained individual aspects of religiosity and control variables. The second model included collective religious characteristics and control variables. To be able to see which aspects of religiosity are related to volunteering behaviour, we included both individual and collective religious characteristics and control variables in the third model. For formal volunteering, we estimated the models 4 and 5. The fourth model was developed to investigate whether religious aspects are related to religious volunteering as well as secular volunteering. In the fifth model we included an interaction term for religious attendance and spirituality to investigate the possibility that the role of religious attendance for volunteering depended on spirituality. For both analyses we present non-standardized coefficients and levels of significance.

Results

Formal Volunteering

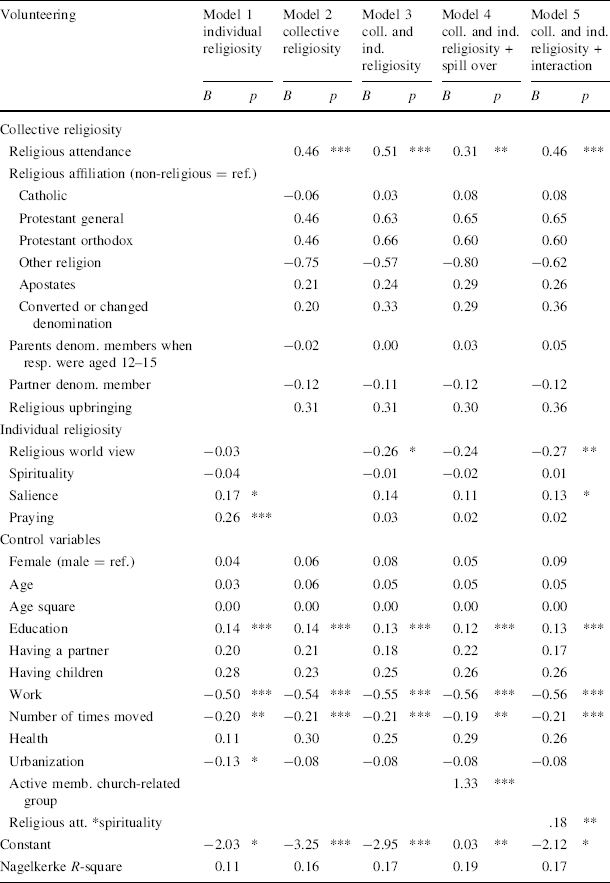

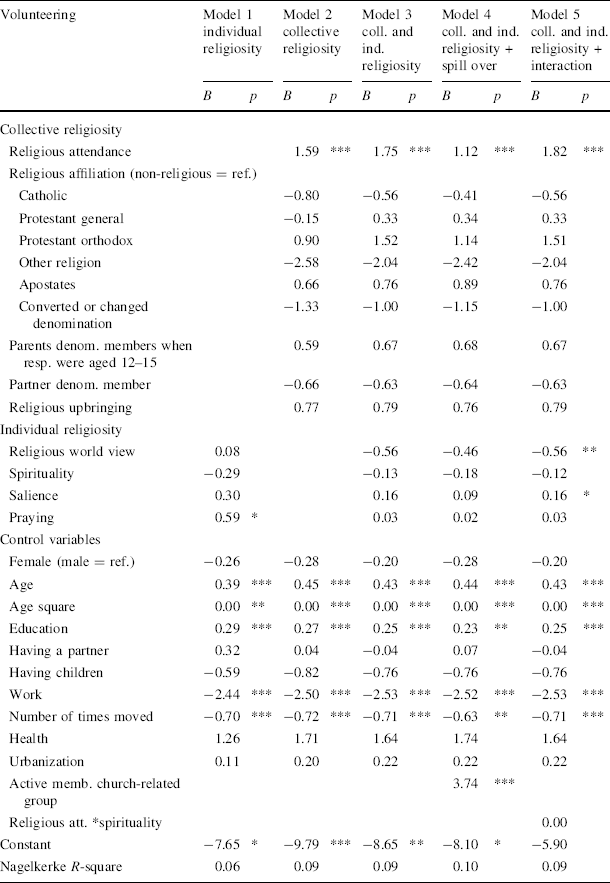

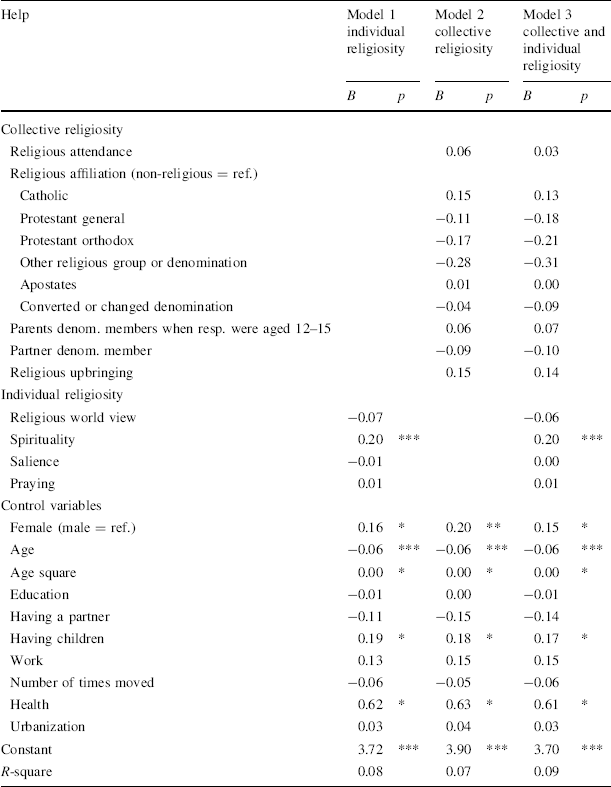

The results of our analyses for formal volunteering are presented in Table 3, which contains several models. The first model shows that saliency of religion and praying are positively related to formal volunteering. The second model includes aspects of collective religiosity and shows that religious attendance increases the likelihood of formal volunteering.

Table 3 Logistic regression models for formal volunteering (n = 1020)

|

Volunteering |

Model 1 individual religiosity |

Model 2 collective religiosity |

Model 3 coll. and ind. religiosity |

Model 4 coll. and ind. religiosity + spill over |

Model 5 coll. and ind. religiosity + interaction |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

|

|

Collective religiosity |

||||||||||

|

Religious attendance |

0.46 |

*** |

0.51 |

*** |

0.31 |

** |

0.46 |

*** |

||

|

Religious affiliation (non-religious = ref.) |

||||||||||

|

Catholic |

−0.06 |

0.03 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

||||||

|

Protestant general |

0.46 |

0.63 |

0.65 |

0.65 |

||||||

|

Protestant orthodox |

0.46 |

0.66 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

||||||

|

Other religion |

−0.75 |

−0.57 |

−0.80 |

−0.62 |

||||||

|

Apostates |

0.21 |

0.24 |

0.29 |

0.26 |

||||||

|

Converted or changed denomination |

0.20 |

0.33 |

0.29 |

0.36 |

||||||

|

Parents denom. members when resp. were aged 12–15 |

−0.02 |

0.00 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

||||||

|

Partner denom. member |

−0.12 |

−0.11 |

−0.12 |

−0.12 |

||||||

|

Religious upbringing |

0.31 |

0.31 |

0.30 |

0.36 |

||||||

|

Individual religiosity |

||||||||||

|

Religious world view |

−0.03 |

−0.26 |

* |

−0.24 |

−0.27 |

** |

||||

|

Spirituality |

−0.04 |

−0.01 |

−0.02 |

0.01 |

||||||

|

Salience |

0.17 |

* |

0.14 |

0.11 |

0.13 |

* |

||||

|

Praying |

0.26 |

*** |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

|||||

|

Control variables |

||||||||||

|

Female (male = ref.) |

0.04 |

0.06 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

0.09 |

|||||

|

Age |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

|||||

|

Age square |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|||||

|

Education |

0.14 |

*** |

0.14 |

*** |

0.13 |

*** |

0.12 |

*** |

0.13 |

*** |

|

Having a partner |

0.20 |

0.21 |

0.18 |

0.22 |

0.17 |

|||||

|

Having children |

0.28 |

0.23 |

0.25 |

0.26 |

0.26 |

|||||

|

Work |

−0.50 |

*** |

−0.54 |

*** |

−0.55 |

*** |

−0.56 |

*** |

−0.56 |

*** |

|

Number of times moved |

−0.20 |

** |

−0.21 |

*** |

−0.21 |

*** |

−0.19 |

** |

−0.21 |

*** |

|

Health |

0.11 |

0.30 |

0.25 |

0.29 |

0.26 |

|||||

|

Urbanization |

−0.13 |

* |

−0.08 |

−0.08 |

−0.08 |

−0.08 |

||||

|

Active memb. church-related group |

1.33 |

*** |

||||||||

|

Religious att. *spirituality |

.18 |

** |

||||||||

|

Constant |

−2.03 |

* |

−3.25 |

*** |

−2.95 |

*** |

0.03 |

** |

−2.12 |

* |

|

Nagelkerke R-square |

0.11 |

0.16 |

0.17 |

0.19 |

0.17 |

|||||

Two-tailed significances: *** p ≤ 0.001; ** p ≤ 0.01; * p ≤ 0.05

The third model reveals that the effects of individual aspects, saliency and praying, disappear when collective aspects are also included in the model. The result that religious attendance is the main determinant of formal volunteering is a replication of results from previous research (Wilson and Janoski Reference Wilson and Janoski1995; Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997a; Becker and Dhingra Reference Becker and Dhingra2001; Lam Reference Lam2002; Ruiter and De Graaf Reference Ruiter and de Graaf2006; De Hart and Dekker Reference De Hart, Dekker and Roßteutscher2005). These results led to a rejection of hypothesis 1, according to which we expected individual religious characteristics to be positively related to formal volunteering. The one exception is the negative effect of a religious worldview that becomes apparent in this third model.

In a fourth model active membership of a church-related association was added, to investigate a possible spill-over effect. The expectation that denomination membership and religious attendance are positively related to formal volunteering even after controlling for people volunteering within their own religious community holds with regard to religious attendance: the more people attend, the more likely they are to volunteer, within as well as outside their own religious community. This result is in line with most recent previous studies on the topic (Cnaan Reference Cnaan2002, pp. 211–233; Reitsma et al. Reference Reitsma, Scheepers and Te Grotenhuis2006b; Ruiter and De Graaf Reference Ruiter and de Graaf2006; Bekkers and Schuyt Reference Bekkers and Schuyt2008).

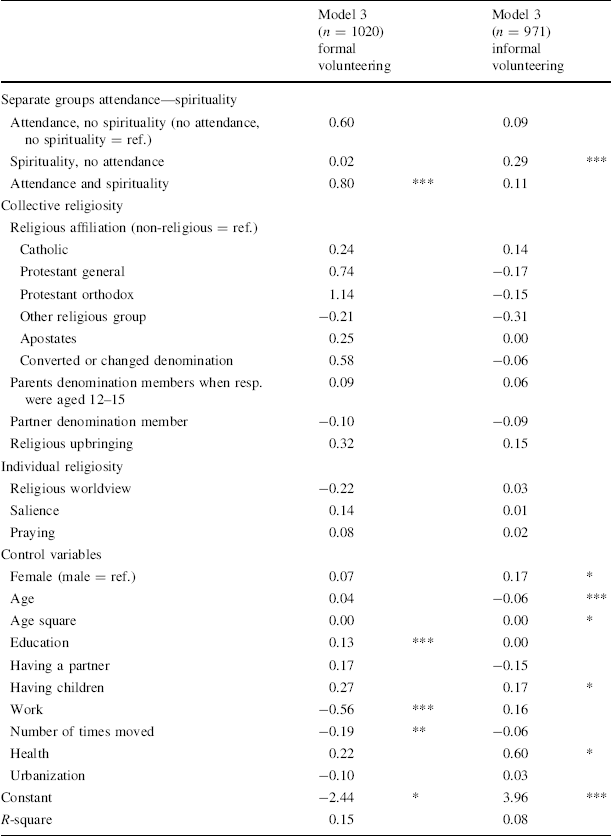

Furthermore, we investigated whether individual religious characteristics were related to formal volunteering when people were integrated into a religious community. Our results confirm this hypothesis (2) with regard to spirituality: the relationship between religious attendance and formal volunteering increases with spirituality, or vice versa, the relationship between spirituality and volunteering does not exist for those who do not attend religious services, but does exist for those who do attend religious services. We did not find other effects of combinations of religious attendance and any of the other individual religious characteristics on formal volunteering.

In line with previous research we found that higher levels of education increase the likelihood of formal volunteering (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997b; Gesthuizen et al. Reference Gesthuizen, Van der Meer and Scheepers2008). Having a paid job and moving decrease the likelihood of formal volunteering. We did not find a relationship between gender, age, health and urbanization on the one hand and formal volunteering on the other.

In short, with regard to religiosity: controlled for a wide range of collective and individual religious characteristics, religious attendance is crucial with regard to formal volunteering.Footnote 6

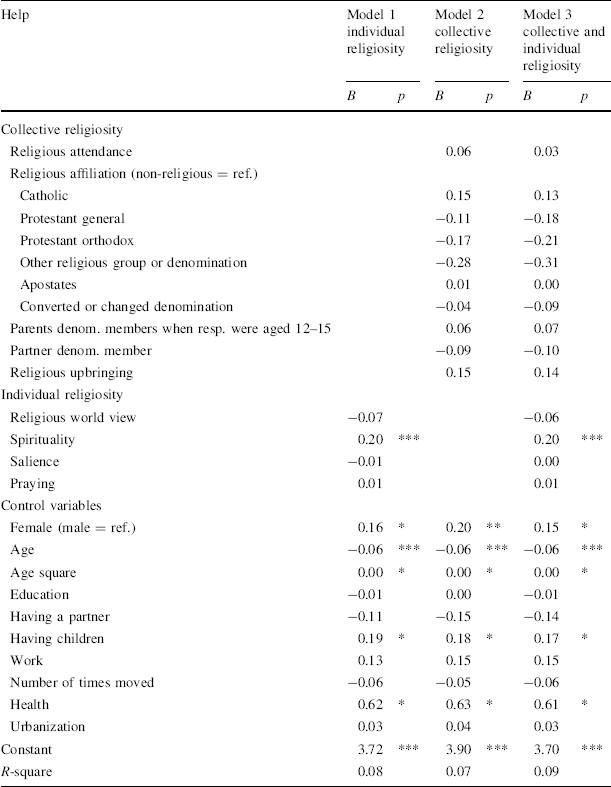

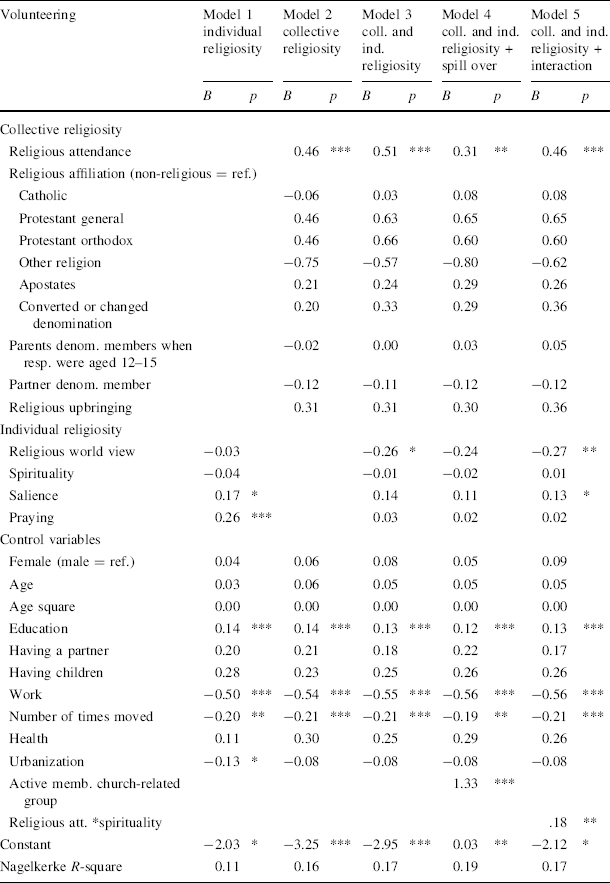

Informal Volunteering

Table 4 shows the results with regard to informal volunteering. The first thing that draws our attention is the low explained variance: although formal volunteering seems hard to explain, the R-square of model 3 is 0.17. Informal volunteering turns out to be even more difficult to predict, with an R-square of 0.09 for model 3. This means that we have to be careful not to describe relationships between aspects of religiosity and informal volunteering as ‘explanations’. However, our findings do show that some characteristics are more important than others with regard to informal volunteering.

Table 4 Linear regression models for informal volunteering (n = 971)

|

Help |

Model 1 individual religiosity |

Model 2 collective religiosity |

Model 3 collective and individual religiosity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

|

|

Collective religiosity |

||||||

|

Religious attendance |

0.06 |

0.03 |

||||

|

Religious affiliation (non-religious = ref.) |

||||||

|

Catholic |

0.15 |

0.13 |

||||

|

Protestant general |

−0.11 |

−0.18 |

||||

|

Protestant orthodox |

−0.17 |

−0.21 |

||||

|

Other religious group or denomination |

−0.28 |

−0.31 |

||||

|

Apostates |

0.01 |

0.00 |

||||

|

Converted or changed denomination |

−0.04 |

−0.09 |

||||

|

Parents denom. members when resp. were aged 12–15 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

||||

|

Partner denom. member |

−0.09 |

−0.10 |

||||

|

Religious upbringing |

0.15 |

0.14 |

||||

|

Individual religiosity |

||||||

|

Religious world view |

−0.07 |

−0.06 |

||||

|

Spirituality |

0.20 |

*** |

0.20 |

*** |

||

|

Salience |

−0.01 |

0.00 |

||||

|

Praying |

0.01 |

0.01 |

||||

|

Control variables |

||||||

|

Female (male = ref.) |

0.16 |

* |

0.20 |

** |

0.15 |

* |

|

Age |

−0.06 |

*** |

−0.06 |

*** |

−0.06 |

*** |

|

Age square |

0.00 |

* |

0.00 |

* |

0.00 |

* |

|

Education |

−0.01 |

0.00 |

−0.01 |

|||

|

Having a partner |

−0.11 |

−0.15 |

−0.14 |

|||

|

Having children |

0.19 |

* |

0.18 |

* |

0.17 |

* |

|

Work |

0.13 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

|||

|

Number of times moved |

−0.06 |

−0.05 |

−0.06 |

|||

|

Health |

0.62 |

* |

0.63 |

* |

0.61 |

* |

|

Urbanization |

0.03 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

|||

|

Constant |

3.72 |

*** |

3.90 |

*** |

3.70 |

*** |

|

R-square |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.09 |

|||

Two-tailed significances: *** p ≤ 0.001; ** p ≤ 0.01; * p ≤ 0.05

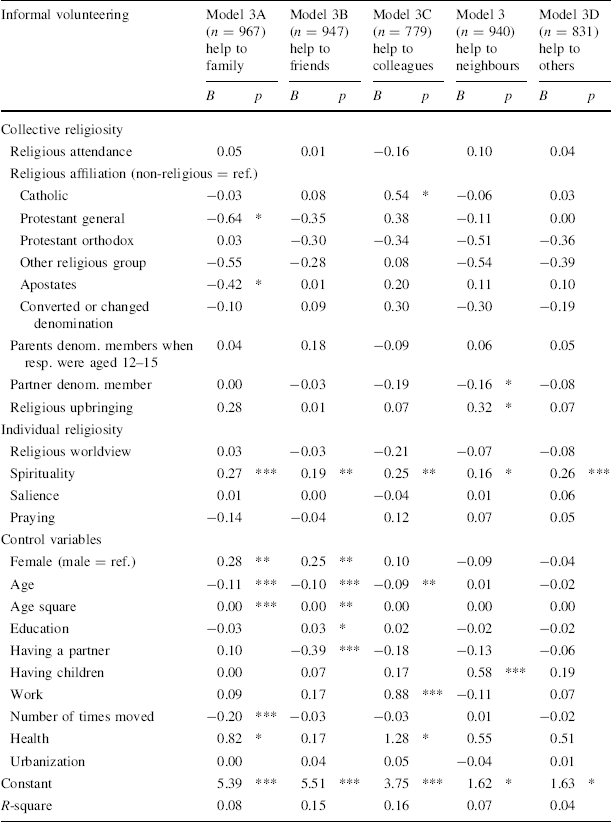

In a first model we investigated the relationship between individual religiosity and informal volunteering, without controlling for collective aspects of religiosity. This model shows that spirituality increases the likelihood of informal volunteering. The second model reveals that collective religious characteristics do not increase the likelihood of informal volunteering. The third model confirms that, even after controlling for collective religiosity, spirituality remains the only individual religious aspect that determines informal volunteering. This finding is in line with recent work of Linders (Reference Linders2010, pp. 183–188) who did not find a relationship between community involvement and helping behaviour.

The effect of spirituality is 0.20, which means that with an increase of 1 in spirituality (ranging from 1 to 5), informal volunteering increases with 0.2. The difference between the lowest and highest value of spirituality is a difference of 0.8 on the scale for informal volunteering, which ranges from 1 (never) to 7 (daily). The relationship between spirituality and informal volunteering is the second largest, after the (negative) relationship between age and informal volunteering. These results confirm hypothesis 1, namely that aspects of individual religiosity increase the likelihood of informal volunteering.Footnote 7

Differential Hypotheses

Our specific hypotheses (1b and 1c) concerning differences in the relationship between individual and collective religiosity on the one hand, and formal and informal volunteering on the other, are partly confirmed by our results. We found a relationship between spirituality, as individual religious aspect, and informal volunteering, while individual religiosity does not play a role with regard to formal volunteering. Therefore, we conclude that our hypothesis that individual religiosity is related stronger to informal volunteering than to formal volunteering (H1b) is supported. However, our prediction that there would at least be a weak relationship between individual religiosity and formal volunteering must be rejected, although individual religiosity plays a role with regard to formal volunteering in that it is a prerequisite for the effect of religious attendance.

With regard to collective religiosity our hypothesis is partly confirmed as well: religious attendance as an aspect of collective religiosity is the main aspect of religiosity explaining formal volunteering, while collective religiosity appears to be unimportant with regard to informal volunteering. Given these findings, collective religiosity is indeed related stronger to formal volunteering than to informal volunteering (H1c), although we were wrong in our assumption that there would also be a relationship between collective religiosity and informal volunteering.

Conclusion and Discussion

How should one interpret the finding that religious attendance is the main religious characteristic determining formal volunteering? Our interpretation is that, to a certain extent, Durkheim’s proposition that integration in a social network is crucial for norm conformity is correct. For formal volunteering, the social network appears to be a crucial factor. This begs the question, why is this not the case for informal volunteering? We therefore looked for an explanation focusing on the differences between formal and informal volunteering: formal volunteering is more indirect and more visible. Higher social pressure within a network can push people to volunteer, but also makes a long-term investment attractive, because the social rewards are higher for those who have been integrated into a religious community. Moreover, it appears that it can generally be said that structural and situational characteristics such as education, work and the numbers of times people moved are relevant with regard to formal volunteering.

The finding that religious attendance is related to formal volunteering is in line with the results of previous studies (Wilson and Janoski Reference Wilson and Janoski1995; Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997a; Becker and Dhingra Reference Becker and Dhingra2001; Lam Reference Lam2002). An additional finding in this study is that the effect of religious attendance on formal volunteering increases for those who are more spiritual, or that the effect of spirituality on volunteering only exists for those who attend regularly.

In our introduction we proposed that a relationship between individual religiosity and formal volunteering might explain why levels of volunteering are relatively stable in the Netherlands even though the levels of religious attendance have seriously declined. As we did not find an independent relationship between individual religiosity and formal volunteering, we have to reject this idea and look for other explanations (Bekkers and De Graaf Reference Bekkers and de Graaf2002; Van Ingen Reference Van Ingen2008; Van Tienen et al. Reference Van Tienen, Reitsma, Scheepers and Schilderman2009).

Furthermore, we found a traditional religious worldview to be negatively related to formal volunteering. We assume that this can be explained by what is known as particularism, which was found to be negatively related to formal volunteering (Reitsma et al. Reference Reitsma, Scheepers and Te Grotenhuis2006b). Particularism means that people consider their own religion exclusive and superior to other religions. We assume that a strong religious worldview is closely related to particularism, because the stronger a person adheres to his or her own religious worldview, the more difficult it will be for that person to be positive about other views. This negative attitude towards other worldviews is related negatively to formal volunteering, because being strongly convinced of one’s own religious ideas is usually thought to make it more difficult to be open to contacts with and investment in people and associations that hold other worldviews. The finding of a clear and stable relationship between religious attendance and formal volunteering strongly supports the idea that a network is important with regard to volunteering. Surprisingly, however, network involvement seems to be unimportant where informal volunteering is concerned. The most significant finding in this study concerns informal volunteering, for which collective aspects of religiosity appear to be unimportant, while spirituality is strongly related to it. This finding, that spirituality is a source of informal volunteering, while community involvement is not, leads to new insights to be explained: why is spirituality a source of informal volunteering and why is this not the case for community involvement? A more intrinsic motivation seems to be required for informal volunteering, which, compared to formal volunteering, is more direct, less visible and in most cases less difficult. Spirituality involves a deep concern with value commitments, the idea that events in life do not occur by chance, ascribing a special meaning to social relationships. This spiritual worldview seems to motivate people to actively intervene when help is needed or asked for. Compared to formal volunteering, characteristics explaining informal volunteering tend to be personal instead of structural: next to spirituality, age, having children and being in good health increase the likelihood of informal volunteering.

In previous research spirituality turned out to be related to openness to change, and universalism, while traditional religiosity is related to conservatism and conformity (Saroglou et al. Reference Saroglou, Delpierre and Dernelle2004; Fontaine et al. Reference Fontaine, Duriez, Luyten, Corveleyn and Hutsebaut2005). This confirms our idea that individual religiosity, spirituality, is more likely to be related to a broad focus on informal volunteering that is not related to a specific goal or subject, while collective religiosity is related to formal volunteering within associations, which is more likely to be sensitive to norm conformity as a motivation.

This means that Durkheim’s theory on the need of community involvement is supported with regard to formal volunteering, but not with regard to informal volunteering. We explained this by the differences between these two types of volunteering: formal volunteering requires people who are involved in and familiar with voluntary associations, and is also more likely to occur within a community where a relatively large number of people volunteer. Whereas informal volunteering involves a wide range of situations in which almost anyone can be an informal volunteer, for example, to help an old neighbour who needs to be taken to see a doctor or a friend who wants to have a heart-to-heart talk. A specific network is less important for informal volunteering. But spirituality, in the sense of regarding social relationships as important and special, can function as a motivation for informal volunteering behaviour.

Now we can answer Wuthnow’s question that we posed in our introduction: ‘Suppose someone claims to be moved by a deep sense of spirituality. Is this faith likely to compel caring activities if it is held apart from involvement in any religious community?’ (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1991, p. 154). With regard to formal aspects of voluntary behaviour, Wuthnow’s answer was: ‘Religious involvement is a prerequisite for the existence of a relationship between belief and care’ (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1991, p. 156). His conclusion with regard to formal volunteering is confirmed in this paper: for formal volunteering, involvement in a religious community seems crucial. However, with regard to informal voluntary behaviour it appears that a deep sense of spirituality increases the likelihood of informal volunteering behaviour, independent of whether or not people are involved in a religious community.

Acknowledgment

We thank John Wilson for the helpful discussion.

Appendix

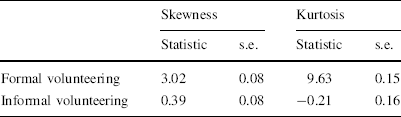

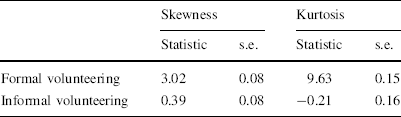

Table 5 Skewness and kurtosis for formal and informal volunteering

|

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Statistic |

s.e. |

Statistic |

s.e. |

|

|

Formal volunteering |

3.02 |

0.08 |

9.63 |

0.15 |

|

Informal volunteering |

0.39 |

0.08 |

−0.21 |

0.16 |

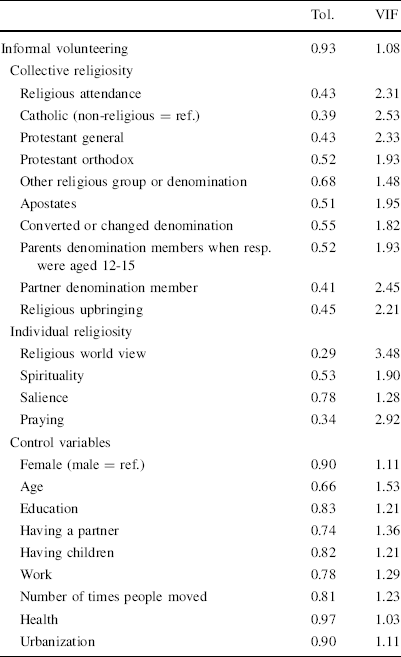

Table 6 Collinearity statistics, dependent variable formal volunteering

|

Tol. |

VIF |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Informal volunteering |

0.93 |

1.08 |

|

Collective religiosity |

||

|

Religious attendance |

0.43 |

2.31 |

|

Catholic (non-religious = ref.) |

0.39 |

2.53 |

|

Protestant general |

0.43 |

2.33 |

|

Protestant orthodox |

0.52 |

1.93 |

|

Other religious group or denomination |

0.68 |

1.48 |

|

Apostates |

0.51 |

1.95 |

|

Converted or changed denomination |

0.55 |

1.82 |

|

Parents denomination members when resp. were aged 12-15 |

0.52 |

1.93 |

|

Partner denomination member |

0.41 |

2.45 |

|

Religious upbringing |

0.45 |

2.21 |

|

Individual religiosity |

||

|

Religious world view |

0.29 |

3.48 |

|

Spirituality |

0.53 |

1.90 |

|

Salience |

0.78 |

1.28 |

|

Praying |

0.34 |

2.92 |

|

Control variables |

||

|

Female (male = ref.) |

0.90 |

1.11 |

|

Age |

0.66 |

1.53 |

|

Education |

0.83 |

1.21 |

|

Having a partner |

0.74 |

1.36 |

|

Having children |

0.82 |

1.21 |

|

Work |

0.78 |

1.29 |

|

Number of times people moved |

0.81 |

1.23 |

|

Health |

0.97 |

1.03 |

|

Urbanization |

0.90 |

1.11 |

Table 7 Linear regression models for informal volunteering for different subjects

|

Informal volunteering |

Model 3A (n = 967) help to family |

Model 3B (n = 947) help to friends |

Model 3C (n = 779) help to colleagues |

Model 3 (n = 940) help to neighbours |

Model 3D (n = 831) help to others |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

|

|

Collective religiosity |

||||||||||

|

Religious attendance |

0.05 |

0.01 |

−0.16 |

0.10 |

0.04 |

|||||

|

Religious affiliation (non-religious = ref.) |

||||||||||

|

Catholic |

−0.03 |

0.08 |

0.54 |

* |

−0.06 |

0.03 |

||||

|

Protestant general |

−0.64 |

* |

−0.35 |

0.38 |

−0.11 |

0.00 |

||||

|

Protestant orthodox |

0.03 |

−0.30 |

−0.34 |

−0.51 |

−0.36 |

|||||

|

Other religious group |

−0.55 |

−0.28 |

0.08 |

−0.54 |

−0.39 |

|||||

|

Apostates |

−0.42 |

* |

0.01 |

0.20 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

||||

|

Converted or changed denomination |

−0.10 |

0.09 |

0.30 |

−0.30 |

−0.19 |

|||||

|

Parents denom. members when resp. were aged 12–15 |

0.04 |

0.18 |

−0.09 |

0.06 |

0.05 |

|||||

|

Partner denom. member |

0.00 |

−0.03 |

−0.19 |

−0.16 |

* |

−0.08 |

||||

|

Religious upbringing |

0.28 |

0.01 |

0.07 |

0.32 |

* |

0.07 |

||||

|

Individual religiosity |

||||||||||

|

Religious worldview |

0.03 |

−0.03 |

−0.21 |

−0.07 |

−0.08 |

|||||

|

Spirituality |

0.27 |

*** |

0.19 |

** |

0.25 |

** |

0.16 |

* |

0.26 |

*** |

|

Salience |

0.01 |

0.00 |

−0.04 |

0.01 |

0.06 |

|||||

|

Praying |

−0.14 |

−0.04 |

0.12 |

0.07 |

0.05 |

|||||

|

Control variables |

||||||||||

|

Female (male = ref.) |

0.28 |

** |

0.25 |

** |

0.10 |

−0.09 |

−0.04 |

|||

|

Age |

−0.11 |

*** |

−0.10 |

*** |

−0.09 |

** |

0.01 |

−0.02 |

||

|

Age square |

0.00 |

*** |

0.00 |

** |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Education |

−0.03 |

0.03 |

* |

0.02 |

−0.02 |

−0.02 |

||||

|

Having a partner |

0.10 |

−0.39 |

*** |

−0.18 |

−0.13 |

−0.06 |

||||

|

Having children |

0.00 |

0.07 |

0.17 |

0.58 |

*** |

0.19 |

||||

|

Work |

0.09 |

0.17 |

0.88 |

*** |

−0.11 |

0.07 |

||||

|

Number of times moved |

−0.20 |

*** |

−0.03 |

−0.03 |

0.01 |

−0.02 |

||||

|

Health |

0.82 |

* |

0.17 |

1.28 |

* |

0.55 |

0.51 |

|||

|

Urbanization |

0.00 |

0.04 |

0.05 |

−0.04 |

0.01 |

|||||

|

Constant |

5.39 |

*** |

5.51 |

*** |

3.75 |

*** |

1.62 |

* |

1.63 |

* |

|

R-square |

0.08 |

0.15 |

0.16 |

0.07 |

0.04 |

|||||

Two-tailed significances: *** p ≤ 0.001; ** p ≤ 0.01; * p ≤ 0.05

Table 8 Logistic regression analyses and linear regression models for formal and informal volunteering, including separate groups: (1) no regular attendance, no spirituality; (2) regular attendance, no spirituality; (3) no regular attendance, spirituality; (4) regular attendance, spirituality

|

Model 3 (n = 1020) formal volunteering |

Model 3 (n = 971) informal volunteering |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Separate groups attendance—spirituality |

||||

|

Attendance, no spirituality (no attendance, no spirituality = ref.) |

0.60 |

0.09 |

||

|

Spirituality, no attendance |

0.02 |

0.29 |

*** |

|

|

Attendance and spirituality |

0.80 |

*** |

0.11 |

|

|

Collective religiosity |

||||

|

Religious affiliation (non-religious = ref.) |

||||

|

Catholic |

0.24 |

0.14 |

||

|

Protestant general |

0.74 |

−0.17 |

||

|

Protestant orthodox |

1.14 |

−0.15 |

||

|

Other religious group |

−0.21 |

−0.31 |

||

|

Apostates |

0.25 |

0.00 |

||

|

Converted or changed denomination |

0.58 |

−0.06 |

||

|

Parents denomination members when resp. were aged 12–15 |

0.09 |

0.06 |

||

|

Partner denomination member |

−0.10 |

−0.09 |

||

|

Religious upbringing |

0.32 |

0.15 |

||

|

Individual religiosity |

||||

|

Religious worldview |

−0.22 |

0.03 |

||

|

Salience |

0.14 |

0.01 |

||

|

Praying |

0.08 |

0.02 |

||

|

Control variables |

||||

|

Female (male = ref.) |

0.07 |

0.17 |

* |

|

|

Age |

0.04 |

−0.06 |

*** |

|

|

Age square |

0.00 |

0.00 |

* |

|

|

Education |

0.13 |

*** |

0.00 |

|

|

Having a partner |

0.17 |

−0.15 |

||

|

Having children |

0.27 |

0.17 |

* |

|

|

Work |

−0.56 |

*** |

0.16 |

|

|

Number of times moved |

−0.19 |

** |

−0.06 |

|

|

Health |

0.22 |

0.60 |

* |

|

|

Urbanization |

−0.10 |

0.03 |

||

|

Constant |

−2.44 |

* |

3.96 |

*** |

|

R-square |

0.15 |

0.08 |

||

Table 9 Linear regression model for formal volunteering, hours volunteering (n = 1,008)

|

Volunteering |

Model 1 individual religiosity |

Model 2 collective religiosity |

Model 3 coll. and ind. religiosity |

Model 4 coll. and ind. religiosity + spill over |

Model 5 coll. and ind. religiosity + interaction |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

B |

p |

|

|

Collective religiosity |

||||||||||

|

Religious attendance |

1.59 |

*** |

1.75 |

*** |

1.12 |

*** |

1.82 |

*** |

||

|

Religious affiliation (non-religious = ref.) |

||||||||||

|

Catholic |

−0.80 |

−0.56 |

−0.41 |

−0.56 |

||||||

|

Protestant general |

−0.15 |

0.33 |

0.34 |

0.33 |

||||||

|

Protestant orthodox |

0.90 |

1.52 |

1.14 |

1.51 |

||||||

|

Other religion |

−2.58 |

−2.04 |

−2.42 |

−2.04 |

||||||

|

Apostates |

0.66 |

0.76 |

0.89 |

0.76 |

||||||

|

Converted or changed denomination |

−1.33 |

−1.00 |

−1.15 |

−1.00 |

||||||

|

Parents denom. members when resp. were aged 12–15 |

0.59 |

0.67 |

0.68 |

0.67 |

||||||

|

Partner denom. member |

−0.66 |

−0.63 |

−0.64 |

−0.63 |

||||||

|

Religious upbringing |

0.77 |

0.79 |

0.76 |

0.79 |

||||||

|

Individual religiosity |

||||||||||

|

Religious world view |

0.08 |

−0.56 |

−0.46 |

−0.56 |

** |

|||||

|

Spirituality |

−0.29 |

−0.13 |

−0.18 |

−0.12 |

||||||

|

Salience |

0.30 |

0.16 |

0.09 |

0.16 |

* |

|||||

|

Praying |

0.59 |

* |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

|||||

|

Control variables |

||||||||||

|

Female (male = ref.) |

−0.26 |

−0.28 |

−0.20 |

−0.28 |

−0.20 |

|||||

|

Age |

0.39 |

*** |

0.45 |

*** |

0.43 |

*** |

0.44 |

*** |

0.43 |

*** |

|

Age square |

0.00 |

** |

0.00 |

*** |

0.00 |

*** |

0.00 |

*** |

0.00 |

*** |

|

Education |

0.29 |

*** |

0.27 |

*** |

0.25 |

*** |

0.23 |

** |

0.25 |

*** |

|

Having a partner |

0.32 |

0.04 |

−0.04 |

0.07 |

−0.04 |

|||||

|

Having children |

−0.59 |

−0.82 |

−0.76 |

−0.76 |

−0.76 |

|||||

|

Work |

−2.44 |

*** |

−2.50 |

*** |

−2.53 |

*** |

−2.52 |

*** |

−2.53 |

*** |

|

Number of times moved |

−0.70 |

*** |

−0.72 |

*** |

−0.71 |

*** |

−0.63 |

** |

−0.71 |

*** |

|

Health |

1.26 |

1.71 |

1.64 |

1.74 |

1.64 |

|||||

|

Urbanization |

0.11 |

0.20 |

0.22 |

0.22 |

0.22 |

|||||

|

Active memb. church-related group |

3.74 |

*** |

||||||||

|

Religious att. *spirituality |

0.00 |

|||||||||

|

Constant |

−7.65 |

* |

−9.79 |

*** |

−8.65 |

** |

−8.10 |

* |

−5.90 |

|

|

Nagelkerke R-square |

0.06 |

0.09 |

0.09 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

|||||

Two-tailed significances: *** p ≤ 0.001; ** p ≤ 0.01; * p ≤ 0.05