Introduction

In the United States (US), the teaching profession is under pressure on many fronts, which has created a worsening teacher shortage in elementary and secondary education. Measures of teacher satisfaction on the job are at historic lows and student interest in becoming teachers has diminished significantly (Kraft and Lyon Reference Kraft and Lyon2024). The economic and social crises precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic have intensified pre-existing problems with chronic understaffing in schools. Many teachers have left the profession, leaving positions unfilled. Recent evidence suggests that teacher shortages are geographically very uneven, with a high degree of variation between and within districts as well as by grade and subject area (Sanderson Edwards et al Reference Sanderson Edwards, Kraft, Christian and Candelaria2024). Higher-poverty districts suffer from some of the worst teacher shortages, intensifying educational and economic inequality in the US (García and Weiss Reference García and Weiss2020, 3).

Recent policies from the US Department of Education (DOE) have focused on increasing compensation, expanding programs for teacher training, promoting professional development and advancement, and increasing the diversity of educators (US Department of Education, 2023). The federal government has encouraged states to use funds from the American Rescue Plan’s Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) program to address the teacher shortage problem (US Department of Education, 2023). Based on a comprehensive analysis of the US teacher shortage, the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) argues that higher wages, increased professional autonomy and greater support for professional advancement are the main ways to increase the attractiveness of the teaching profession and recruit and retain teachers (García and Weiss Reference García and Weiss2020).Footnote 2

While we are supportive of the above policy proposals, we are interested in exploring how work-time reductions could be utilised as a way to improve the teaching profession. Our vision for work-time reductions would include shorter contracted hours without loss of pay for teachers and would not affect instructional time for students. Such a scheme would contract teachers to work fewer hours than students are required to be in school.

The policy would require job sharing as a way to cover all of the time and curriculum content currently included in public school days. Thus, this plan would require significant investment for hiring more teachers and would only be possible if the change in policy helped schools retain and attract qualified educators. ///

Our vision is in sharp contrast to the four-day school week that has been implemented in various states. These districts typically do not hold school on Friday and either lengthen the other four days or obtain waivers for instructional time (NCSL [National Conference of State Legislatures] 2023). While this approach has helped some districts attract and retain teachers, closing school on the fifth day imposes costs on parents and other caregivers, who need to organise care for their children. It also exposes children who rely on school meals to hunger and food insecurity (Abramsky Reference Abramsky2024). The four-day school week is typically implemented to reduce costs in transportation, energy or other expenses—which is why we call this the ‘austerity approach.’

In contrast, our vision is that reduced working-hours for teachers—without sacrificing teacher pay or hours of school for students—would improve education through a significant commitment of additional resources. We believe that this would lead to a variety of positive externalities for the school and greater community—including a potential improvement in job quality in related and unrelated sectors—which is why we call this idea the ‘abundance approach.’ Williamson et al (Reference Williamson, Cooper and Baird2015) found that a benefit of job sharing for teachers was improved work-life balance. However, the problem of unpaid overtime in job sharing schemes was not resolved, as co-teaching involves coordinating and collaborating with colleagues. If implemented universally within a school, job sharing could become ‘quality, part-time work’ that has the ‘potential to disrupt’ the highly gendered working regimes in which men have full-time careers, and women are pushed into contingent labour in order to fulfil their care responsibilities at home (Williamson et al Reference Williamson, Cooper and Baird2015).

Historically, the labour movement has emphasised reducing the length of the working day as a focal point of collective struggle. Over the last century, however, US workers and unions have favoured the individual pursuit of income through the hoarding of hours (Linder Reference Linder2000, Reference Linder2002). Indeed, long work hours have become a feature of various advanced economies, despite previous legislative victories (Campbell Reference Campbell2007). Recently, interest in work-time reductions has re-emerged in the US political landscape, as evidenced by legislation introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders and Representative Mark Takano in 2024. Teachers are among the most important sections of the US labour movement today, which makes us believe that they could be important leaders in the fight for shorter working hours.

We view teachers and the teaching profession through the lens of feminist political economy and related disciplines.Footnote 3 Teaching is still a predominantly female profession in the US. Women comprise 80% of elementary and middle school teachers and 57% of secondary teachers.Footnote 4 A feminist perspective emphasises the role of gendered norms in political economic processes and outcomes. Feminist economics and feminist sociology both emphasise the relevance of paid and unpaid care work to the economy and women’s subordinate status relative to men (Moos Reference Moos, Berik and Kongar2021a). These disciplines also study the unique challenges faced by caring professionals such as educators, especially in the context of neoliberal policy reforms.

The struggle over the length of the workday is a core concern of feminist political economy. As Moos (Reference Moos2021b) argues, conflicts over the length of the workday have both a class and gender dimension. The total working day includes both paid work and unpaid household production. For this reason, the regulation of women’s working hours has historically been at the forefront of the development of labour law and policy (Moos Reference Moos2021b). Regulations of working hours emerge as the outcome of struggles between actors with diverging interests, but also in response to the collective action problems among those actors themselves. Feminist political economy sheds light on the over-exploitation that results from the uncoordinated action of working-class households and employers (Moos Reference Moos2021b).

Literature on the ‘care work wage penalty’ demonstrates that workers in care sectors, such as teachers, experience a wage penalty when compared to workers in non-care sectors with comparable levels of education. England et al (Reference England, Budig and Folbre2002) attribute the care work wage penalty to the economic dependence of care recipients, such as children; the association of care work with femininity and mothering and the devaluation of such labour; the difficulty in increasing productivity in care work without decreasing quality of care services and the possibility that the intrinsic motivation of care workers allows employers to depress wages. Folbre et al (Reference Folbre, Gautham and Smith2023) argue that the care work wage penalty is also due to the fact that the outcomes of care work are hard to measure, and assessments of quality are subjective. Care work creates positive externalities that are not reflected in care workers’ wages. They also argue that because consumers have limited information or choice, these professions tend to encourage low wages and high turnover. Finally, the ‘duty to care’ can be enforced through external pressures coming from law, management or culture—as well as internal ones through the care workers’ values and commitments.

Literature on the teaching profession demonstrates that neoliberal policy imperatives, such as austerity measures, school choice and the expansion of high-stakes standardised testing, demand more from teachers whilst providing fewer resources to public schools. As noted by Torrance (Reference Torrance2017), Gavin et al (Reference Gavin, Fitzgerald and McGrath-Champ2022a), Gavin et al (Reference Gavin, McGrath-Champ, Wilson, Fitzgerald, Stacey, Riddle, Heffernan and Bright2022b) and Stacey et al (Reference Stacey, Wilson and McGrath-Champ2022), when neoliberal logic is applied to education policy, individual actors such as teachers, students and parents—rather than the state—are made responsible for student outcomes, obscuring the underlying socioeconomic context in which public education exists. Therefore, such policies have affected not only the level of available funding at the district or school level but also the individual and collective mindsets of educators through what these researchers call the ‘responsibilising of teachers.’

This study seeks to understand attitudes among teachers regarding the desirability of work-time reduction as a goal of collective bargaining. US teachers are more likely than workers in other occupations to have a spouse in the workforce and children in their care.Footnote 5 Time pressures on dual-earning households are hypothesised as a reason for overwork and work-time conflicts for teachers (Drago et al Reference Drago, Caplan, Costanza, Brubaker, Cloud, Harris and Kashian1999). This suggests that as a group, teachers will be particularly sensitive to hours as a component of working conditions. However, little is known about the specific role of work hours in attracting teachers to the profession, as well as in generating turnover.

To assess the interest in work-time reductions, we conducted four focus group interviews and collected time diaries of a sample of public school teachers in Massachusetts between November 2023 and March 2024. Popular and financial press consistently ranks Massachusetts among the US states with the highest quality of public education (McCann Reference McCann2024). In 2022, Massachusetts districts spent on average USD 17,136 annually per pupil, making it the seventh highest spending state in the US (Gillian Reference Gillian2022). Yet, in 2023, Massachusetts teachers experienced a −19.9% wage gap when compared to other college-educated professionals in the state (Allegretto 2024). Furthermore, per pupil spending and teacher salaries in Massachusetts vary dramatically by district due to the reliance on local property taxes. In other words, students and teachers alike are affected by economic stratification and inequality.

Massachusetts public school teachers are covered by the Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA), which is affiliated with the National Education Association (NEA), the largest labour union in the United States. The MTA represents 117,000 members, including teachers, professors, education support professionals and professional staff in public schools, colleges and universities in 400 local affiliate organisations (Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA), nd). In Massachusetts, collective bargaining between public sector workers and employers is governed by the Massachusetts Public Employee Collective Bargaining Law, under the auspices of the Massachusetts Department of Labor Relations (MA DLR 2017). Collective bargaining agreements are usually negotiated between local teachers’ unions and school district representatives. While having a right to engage in collective bargaining, public sector employees, including teachers, do not have the right to strike in Massachusetts. Nevertheless, in recent years, numerous Massachusetts teachers’ unions have engaged in illegal strikes, resulting in important labour victories but also expensive legal battles with their school districts (Rex Reference Rex2024). The MTA has made legalising the right to strike a priority for educators, along with higher salaries, free higher education and improvements in school funding and teachers’ pensions (Cristantiello Reference Cristantiello2025).

Our analysis documents a common experience of overwork and a significant ‘mental load’—both of which affect teachers’ quality of life, physical and mental health, relationships with their families and desire to keep teaching. While participants were union members and therefore experienced with collective bargaining, most approached the issue of overwork as an individual problem that must be solved by setting and maintaining personal boundaries. Focus group participants differed in their assessment of a hypothetical policy proposal for a work-time reduction without a loss of pay for teachers or instructional time for students. While generally supportive of the goal, participants questioned whether contractual reductions would correspond to actual reductions in hours worked. Discussions revealed that teachers’ professional identities as hard-working and caring ‘perfectionists’ inhibited their policy imaginations with regard to using collective bargaining to win them additional leisure time.

This paper will have the following structure. The second section presents our methods and data. The third presents the results of our focus groups regarding overwork. The fourth section presents our findings of teachers’ perception of work-time reduction without loss of pay. The fifth discusses the relationship between teachers’ overwork and their policy imaginations as evidenced by our discussions. The final section presents our conclusions.

Methods and data

Focus group interviews were chosen as a suitable method to efficiently collect data on the range of opinions and perspectives on a topic among a set of participants with similar backgrounds (Hennink Reference Hennink2014). The focus group discussions completed during the 2023–2024 school year were complemented with data collected through an online survey that was distributed to participants in advance of the focus group meetings. In addition to information about teachers’ demographics, family composition and teaching experience, the survey contained a time diary. Retrospective time diaries are recognised as a superior method for estimating the total time devoted to particular activities (te Braak et al Reference te Braak, Van Droogenbroeck, Minnen, van Tienoven and Glorieux2022; Hunter Gibney et al Reference Hunter Gibney, West, Gershenson, Hamermesh and Polachek2022). Teachers were asked to report their activities during the 24 hours covering their last typical workday when they taught in a classroom.Footnote 6 They were also asked to estimate the total time devoted to various work activities during a typical weekend.Footnote 7

Each of our four focus groups was conducted using a video-conferencing platform at a mutually convenient time in the late afternoon; each lasted one hour.Footnote 8 The conversations began by asking participants to reflect on the process of filling out the time diary. We then discussed how teachers’ work hours and workload affected their quality of life and work satisfaction. The second part of the focus group conversation covered work-time reductions. We prompted participants to imagine an eight-hour reduction in the contracted work-time and discuss implications for their life. Finally, we asked teachers about their relative preferences for a pay rise at constant hours, or a work-time reduction at constant pay.Footnote 9

Each member of the research team separately coded the focus group transcripts in an open-ended fashion. The codes were then compared and harmonised, and a basic analytical framework developed to structure the emerging concepts. The focus group transcripts were then recoded using the harmonised coding structure.

Analytical framework

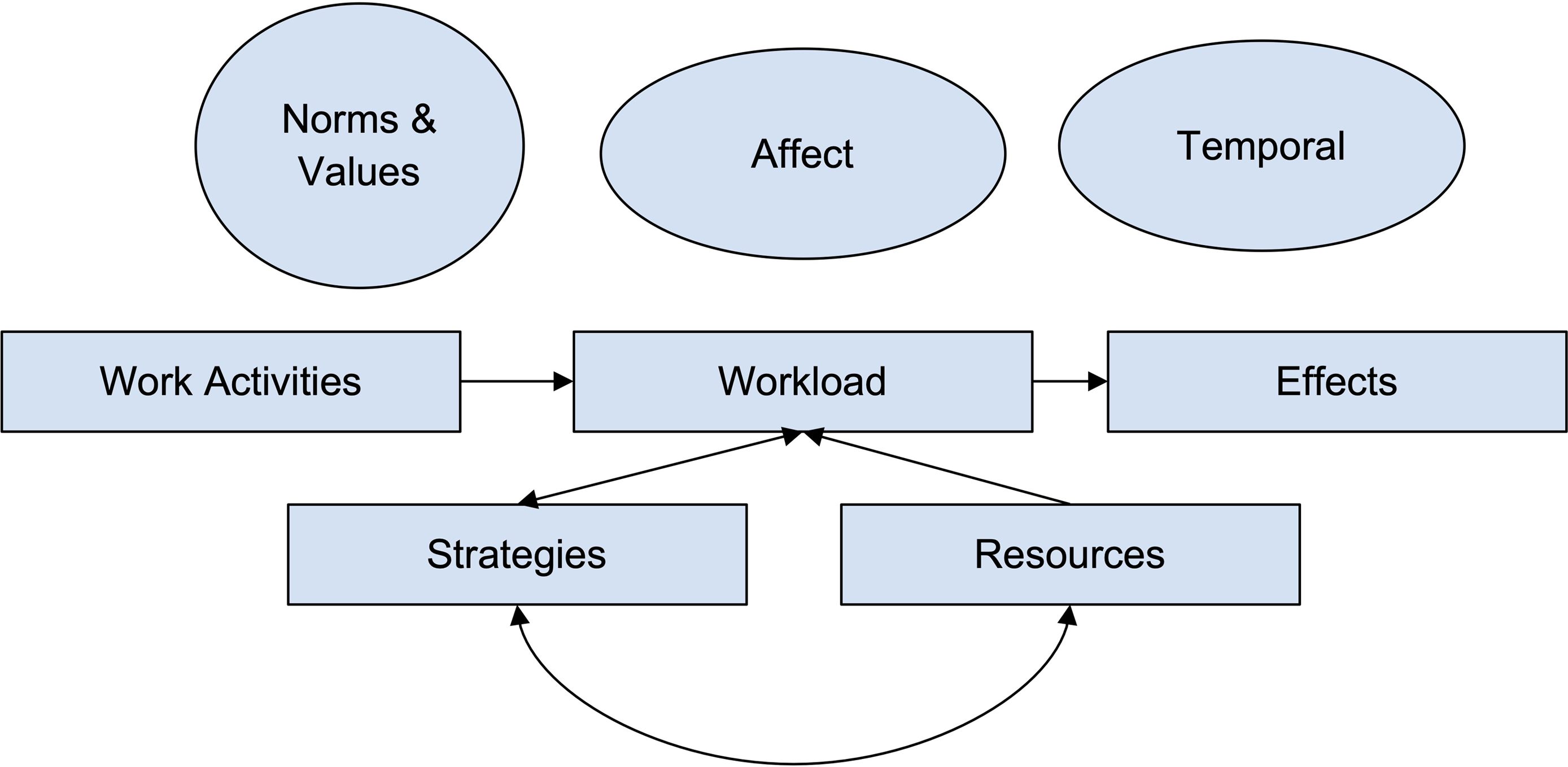

Based on an initial round of coding, we developed a rudimentary framework to organise our codes and provide a scaffold for our analysis (Figure 1). We conceived of the teachers in our focus groups as performing work activities that generate a certain workload, mobilising resources to implement strategies to manage their workloads and describing the effects on themselves and others. We also kept track of the norms and values mentioned by teachers, as well as any relevant affective and temporal aspects of their descriptions. Consistent with the Jones et al (Reference Jones, Camburn, Kelcey and Quintero2022) study of teachers, we broadly considered teachers’ affective states as positive or negative affect—both of which can influence student learning outcomes and experience of school.

Figure 1. Analytical framework.

Participants

We identified classroom teachers in Massachusetts public schools for first through twelfth grades as the population for our study. We sought to recruit approximately equal shares of elementary, middle and high school teachers. The Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA) shared a recruitment blurb with their membership in a weekly email. We were also able to share our recruitment material with a Facebook group of thousands of Massachusetts educators.

More than one hundred teachers completed the screening questionnaire, including many Education Support Professionals (ESPs) and teachers in special education and Kindergarten. We had previously decided to only include teachers for first through twelfth grade, so ESPs, Kindergarten, and special education teachers were excluded.Footnote 10 Out of the remaining roughly 50 eligible potential participants, we were able to schedule focus group meetings with a total of 19 classroom teachers.

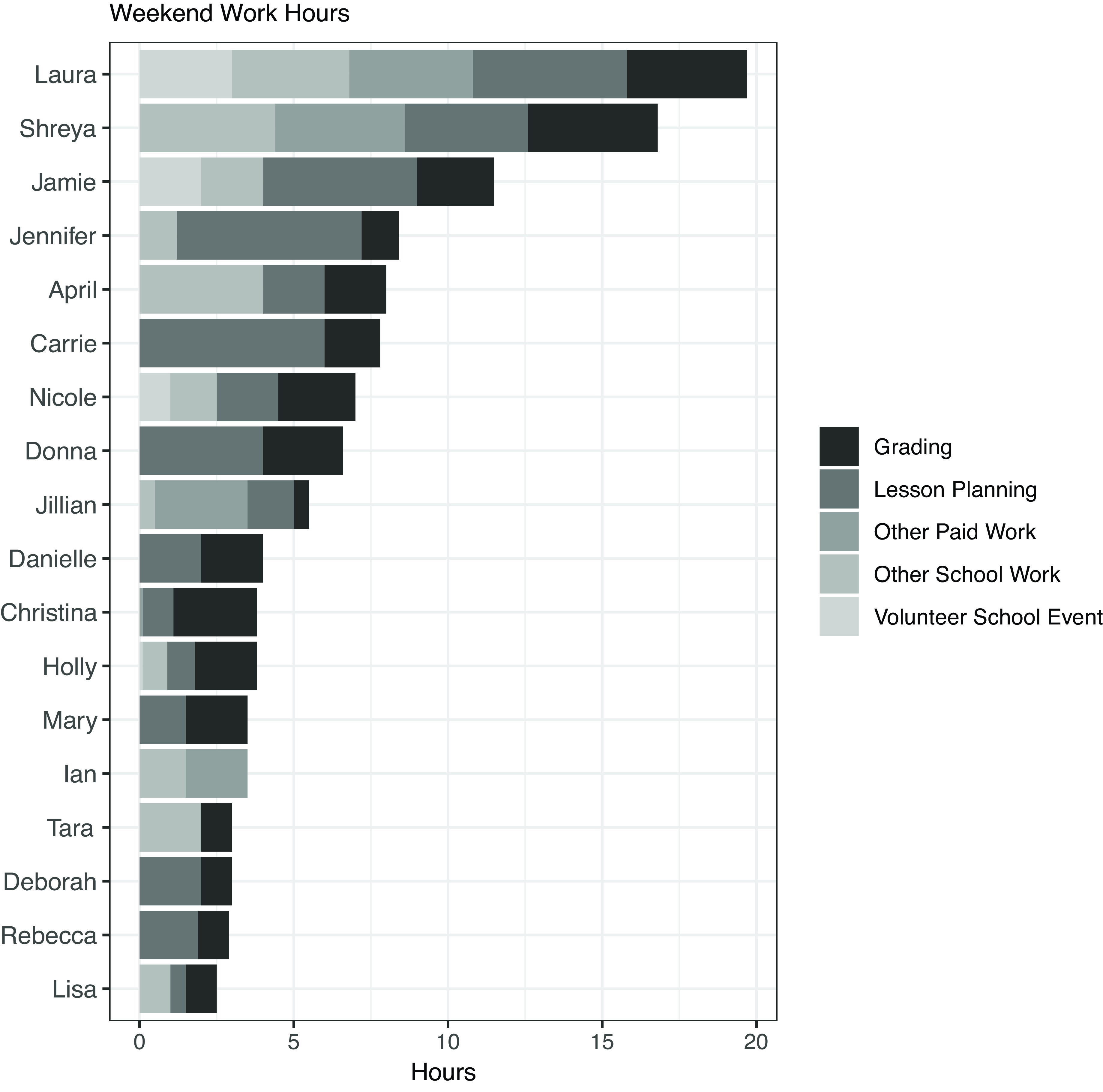

Three focus groups were organised, stratified by grade level. A residual ‘All Levels’ group was added to maximise participation, which included five elementary school teachers and one middle school teacher. Although we did not seek to homogenise the groups in other ways, the sample was very homogeneous in terms of demographic characteristics like gender, racial and ethnic backgrounds and teaching experience (see Table 1). While seven teachers said that they had children in their care, only one teacher had children younger than 11 years old.

Table 1. Characteristics of focus group participants.Footnote 14

Findings

The state of overwork for Massachusetts teachers

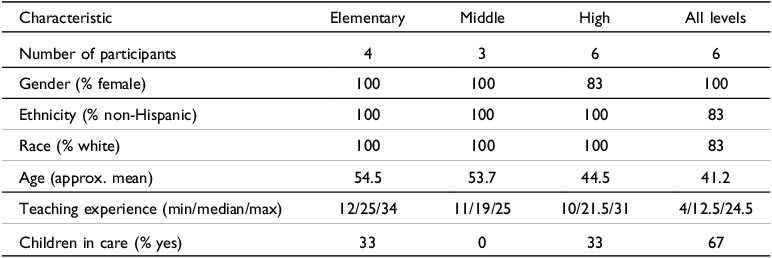

Figure 2 displays the cumulative time devoted to paid and unpaid work activities during the last typical workday when participants were teaching in a classroom (names have been changed to protect anonymity and confidentiality). Teaching work was defined as the sum of time devoted to teaching and teaching replacement work, as well as a list of eight other peripheral teaching activities (see Appendix A for the list of activities). The average time spent on teaching work was 8.8 hours and ranged from a minimum of 6.8 to a maximum of 12. Combining unpaid domestic work, time spent commuting to and from work and time spent on paid work outside education,Footnote 11 the average total work day was 11.5 hours, with a minimum of 8 and a maximum of 15.1. These findings are consistent with the results in Drago et al (Reference Drago, Caplan, Costanza, Brubaker, Cloud, Harris and Kashian1999), which used time use diaries to estimate time use among teachers and also found that actual working hours were consistently longer than contracted hours.

Figure 2. Teachers’ cumulative time devoted to paid and unpaid work during the last typical teaching day.

While not a major topic in the focus groups, commuting time is relevant due to the high cost of housing in Massachusetts. Massachusetts ranks third out of US states for highest home prices and second highest for overall cost of living (Chakraborty Reference Chakraborty2024). Housing prices in the Greater Boston area are especially high. Several participants mentioned that they were able to buy houses—an important marker for economic security and wealth building in the US—but not in the districts where they work. One teacher mentioned buying a house in a neighbouring state where home prices are lower. The high cost of housing puts additional pressures on teachers’ finances and time. The necessity to live in lower cost cities and neighbouring states undermines teachers’ ability to live in the communities where they teach.

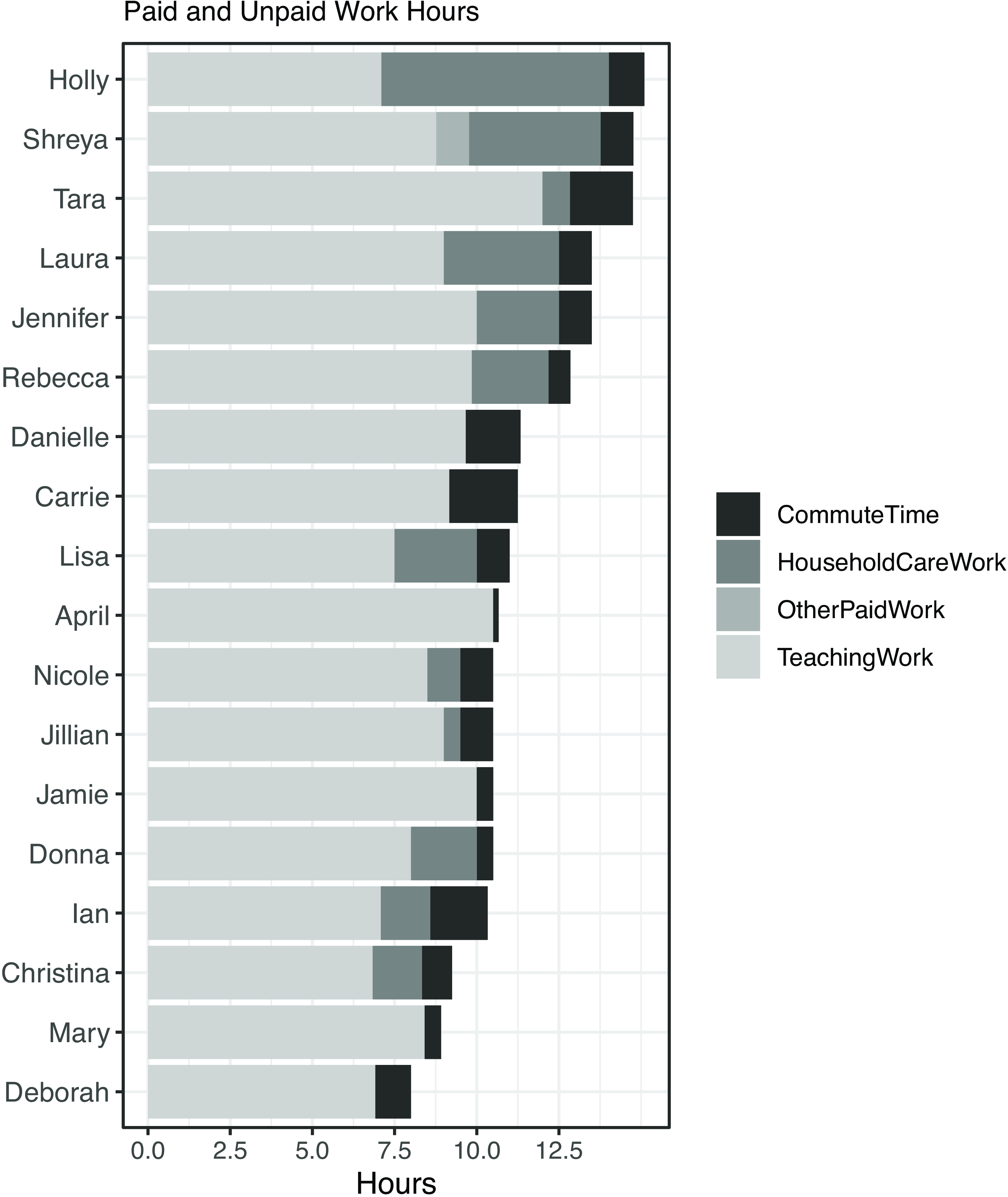

Figure 3 shows the time devoted to various activities related to teachers’ primary job as well as other employment during a typical weekend. Unlike the previously reported work hours from a typical teaching day, which were inferred from the time diary responses, teachers were asked to estimate their total work hours. Even allowing for some upward bias in these survey estimates compared to more accurate time diary based estimates, the work hours during weekends for some of our teachers were very long. Focusing narrowly on grading, lesson planning and other school work, we find a range of 1.5 to 12.7 hours, with a typical teacher in our sample working 3.85 hours during the weekend.

Figure 3. Total time devoted to teaching, other work and school-related volunteering during a typical weekend.

Teachers’ reflections on their time diaries

We began our discussions with focus group participants by asking them to reflect on the experience of filling out the time diary. The act of accounting for how they spent their time during the previous work day brought up uncomfortable realisations for some participants:

I can get to work at 6:30 in the morning, and sometimes I’m there until 6:30 at night… I never really stopped and thought about just how much of my day is focused on just being in school and dedicating that time to school. – Jamie (middle school).

While not every teacher reported working excessively long days, our discussions revealed that long working hours are a normalised feature of the teaching profession. Other teachers echoed the sentiment that long workdays are common, but not reflected upon until doing the time diary.

Several teachers mentioned waking up, either in the morning or in the middle of the night, thinking about their teaching responsibilities or other issues relevant to their schools. Disrupted sleep is a common experience for people with stressful life circumstances and jobs. The act of filling out a time diary prompted teachers to think about this time as part of their workday—what we call the ‘mental load’—rather than simply as a private experience.

The mental load appeared to be a contributing factor to the long working day for several teachers. Many teachers mentioned that they were thinking about their work even when not physically at school, such as planning lessons while driving home. The time diary only asked for primary activities (such as commuting) and did not ask what people were thinking as they were doing this activity. However, the act of filling out the time diary made teachers more aware of not only their activities but also the secondary activities—such as lesson planning or worrying about students—and the thoughts and feelings that accompanied them.

The discussions revealed that teachers work many hours in addition to their contracted hours to get all of their work done, especially for preparation, planning, grading and communication with colleagues and parents. Teachers repeatedly articulated that these additional hours of work were unpaid. The time diaries measured how much additional time teachers put into teaching, especially for planning and grading.

Teachers also noted that the discrepancy between their contracted and actual hours leads to the profession being misunderstood by the wider public. While the school day ends earlier than other professional jobs, teachers reported being unable to complete all of their necessary tasks within their contracted preparation time. The idea that teachers work shorter hours than other professions was also echoed by some teachers themselves, especially those who had worked in other industries prior to becoming teachers. Yet, these same teachers reported working many more than their contracted hours. It appears that the contracted hours obfuscate the actual hours worked by teachers, even in their own minds.

Work activities and emotions

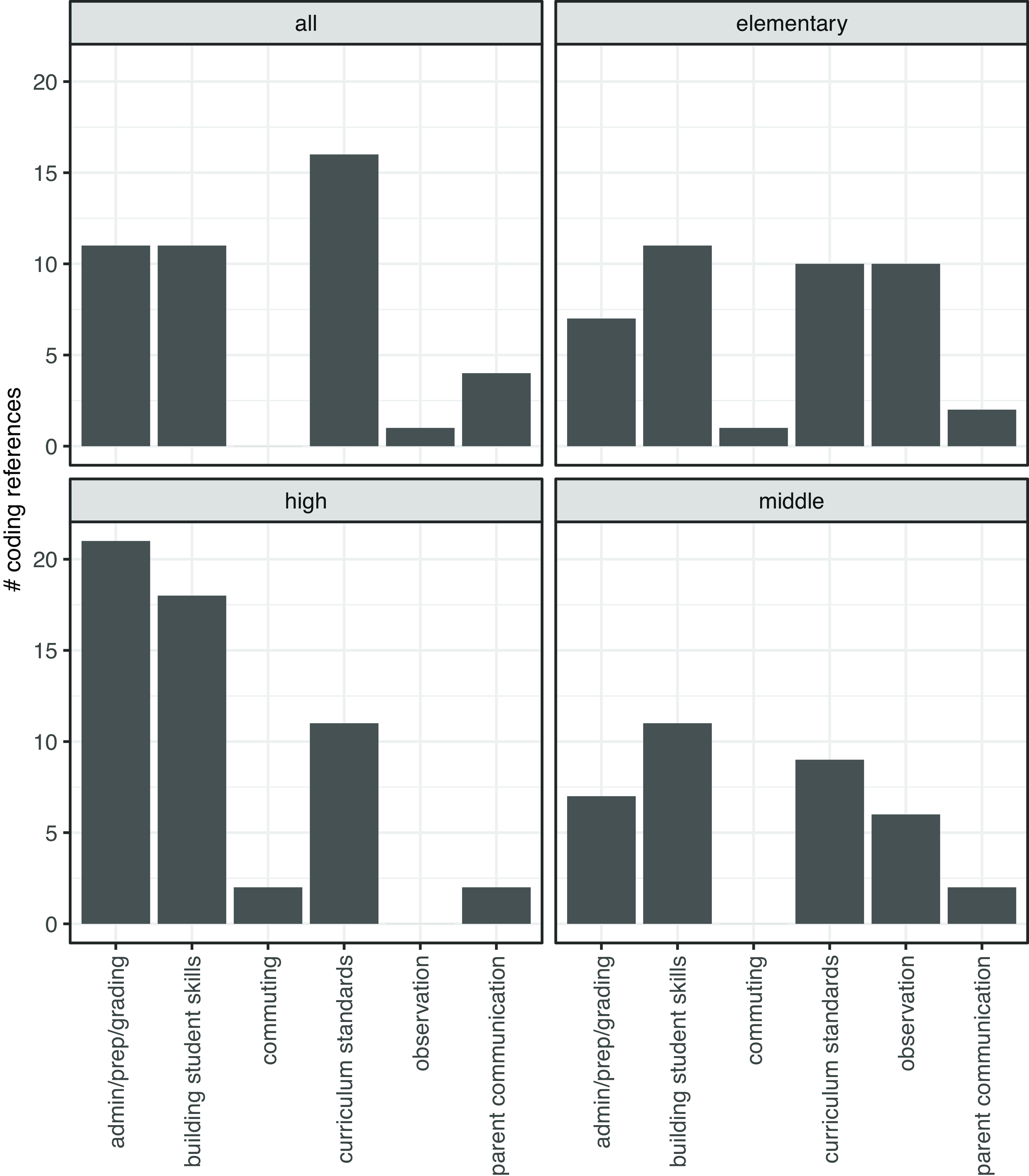

Figure 4 illustrates the frequency with which different work activities appeared in our discussions. The most talked about activities related to administrative and peripheral teaching work (such as preparation and grading), building student skills (which includes social-behavioural, academic, remedial and special education) and meeting curriculum standards (which includes discussion of standardised testing and curriculum chosen by others).

Figure 4. Prominence of work activities in focus group discussions.

Observation by supervisors was mentioned frequently by elementary and middle school teachers, who described it as intimidating and time consuming:

[Being evaluated] is pretty much the most stressful thing I do all year… that is just about the worst thing that I bring home because, you know, it just seems pointless, difficult, kind of scary. (Mary, middle school).

Negative feelings, especially of overwhelm and exhaustion, were common topics. Such feelings were often paired with very high standards and expectations for themselves. Teachers expressed the desire to provide a high standard of education in the classroom, through grading and evaluation, and by communicating with parents:

I constantly feel overwhelmed. I cannot keep up with my work… I do a good job. But I don’t feel that I’m doing as good a job as I could be doing if I had fewer students [and] if I didn’t have 3 preps (Holly, high school).

In addition, the pressures put on teachers by the increasingly complex learning, social and behavioural needs of students were a frequent topic. There are many students with learning disabilities or other needs warranting Individual Education Plans (IEPs), which require accommodations, meetings and paperwork. While teachers did not express an unwillingness to meet the requirements of IEPs for their students, they did comment on the time and stress that it added to their workloads. The effort to meet each individual student’s needs puts demands on teachers’ time and contributes to feelings of overwhelm.

Diminished autonomy over curriculum decisions was another cause of teachers’ frustration. While there is an emphasis on social and behavioural learning, there are also increased educational standards that some teachers believe are inappropriate for children’s age or poorly designed. Experienced teachers felt that the standards have become inappropriately high, and that students are expected to do things that previous generations of students were not expected to accomplish at a given grade.

The difficulty of meeting both high curriculum standards and increasingly complex social and behavioural needs came up frequently. Teachers attributed their increased workload in part to the COVID-19 pandemic, in which students required additional help and experienced learning loss associated with remote schooling. A common theme expressed by teachers was that both social-behavioural and basic skills were underdeveloped. This concern was articulated by Laura (elementary school):

But one thing I am noticing [coming back] from [remote learning during] COVID is that these children have a lot of difficulty with social skills… They just cannot converse with each other without an argument. Socially, they’re so far behind. Another thing is cutting paper, colouring in a piece of paper, picking up a pencil off the floor. I think either they just didn’t know how to do these things during [remote schooling]… or didn’t have the resources.

Overall, the results point to the increasing task complexity confronting teachers, especially in the wake of COVID-19.

The consequences of overwork on teachers’ health, family and well-being

Figure 5 illustrates the frequency of discussion on the consequences of overwork on teachers’ lives. The main topics that arose were how the workload affected family life, personal health and desire to keep teaching. Discussions on the desire to keep teaching were almost always associated with negative affect—in other words, with the desire to not continue teaching. In some focus groups, the effects on family life and health dominated, such as the ‘all levels’ group, which contained a larger share of parents than the other groups. The desire to keep teaching was a particularly prominent topic of discussion in the elementary teachers group.

Figure 5. Prominence of consequences of overwork in focus group discussions.

Some of the comments made by teachers described very strong responses to the experience of overwork. Several teachers described adverse effects of the workload on their physical and mental health:

I am running on empty. This job has consumed my life—mentally, emotionally, physically—especially in the last 4 or 5 years, but this year is just [the worst]… I threaten all the time that I’m going to go on medical leave to my principal (Rachel, elementary school).

While this was not universal, Rachel’s experience demonstrates that teachers can experience adverse mental and physical health effects as a result of their workload. This can make the idea of leaving the teaching profession attractive, even necessary.

In addition to the stress put on teachers’ own health, several participants mentioned that the stress of the teaching job strained their relationships with their families and children:

You’re constantly thinking about this job. You’re constantly thinking about your [students]… I think people don’t realize how much more stress we put on ourselves as educators… I think sometimes our own [family life] is a little wild because we’re too busy thinking about other people’s kids (Laura, elementary school).

While Laura emphasised the mental load, the comments of other participants demonstrated that the intensity of the workday during contracted hours, as well as the necessary tasks that teachers were completing outside of contracted hours, took time and energy away from their own children.

Our discussions demonstrated that teachers, especially those who are parents, are under significant time pressures that compound with their high expectations for themselves as educators. Even teachers who have decades of experience find themselves unable to complete all of their necessary work with the demands of their home life:

I’m 20 years in [my teaching career] and I also have a child. And so I have to leave [work] at work. But it stresses me out, and it’s tricky because what ends up happening is… it takes me 3 weeks or a month to grade. And it feels unfair to my students whereas if I were to have the time to do it at home, I could get it done a lot quicker, but I just can’t… especially later at night, after dinner’s made… I’m usually just about ready to fall asleep… It affects my quality of life at home definitely (Holly, elementary school).

Even teachers who do not complete significant amounts of school work at home experience this as a conflict. Feelings of guilt towards students, even when experiencing exhaustion and the physical inability to work more, were common.

Numerous participants who are also parents expressed frustration at the conflicts that their job poses in terms of allocating time and attention from their students at school and their children at home. Regarding the consequence of working through her students’ behavioural issues taking away time and energy for her children at home, Shreya (elementary school) remarked:

I find that when my kids [at home] want my attention, I’m taxed… my time is [taken away] from my kids at home, ’cause I’m on my phone, or I’m sending an email, or I’m sending a text [about my students].

Participants demonstrated a high degree of emotional connection, personal investment and care towards their students. Underlying many of these comments was a clear desire to be fully present and available for both groups of young people—their own children and their students—and strong feelings of guilt and regret when they find themselves unable to do so. As Drago (Reference Drago2001) has argued, the ‘norms of parental care’ that expect teachers to mother their students as if they are their own children has existed since the nineteenth century. The professionalisation of teaching led to the ‘ideal working norm’ being applied to teachers, lengthening their work hours. As the former did not disappear when the latter was introduced, the combined effects of these ideas have led to long days for teachers that may undermine the time they have for their own children.

The conversations about the effect of the workload on teachers’ health, well-being and family life were also tied to the recent experience with remote teaching during the pandemic. The pandemic was a time of extraordinary stress and pressure on everyone—most notably caregivers of all kinds. Yet, the effects on teachers’ work habits—especially being available to students and families outside of the normal school day—appear to have outlasted the years of remote schooling:

Things changed for me coming out of COVID, working remotely… I was practically working 24/7, and my family took a big back seat to it. My physical health and my mental health took a huge hit. It took me a year or two to kind of figure out, hey, that’s not okay, right? Like, I need to come first. My family needs to come first (Carrie, elementary school).

Many teachers mentioned the need to reassess their workload and how remote learning affected their work habits. As Hunter Gibney et al (Reference Hunter Gibney, West, Gershenson, Hamermesh and Polachek2022) have argued, even prior to the pandemic, teachers experienced ‘blurrier work-life boundaries’ than other professionals. Remote instructions intensified this and has had major implications for teachers’ time use. In the years following the return to regular schooling, teachers are having to figure out on their own what expectations are appropriate for themselves as educators, as a means of protecting their own health, well-being and family life.

Strategies for dealing with overwork

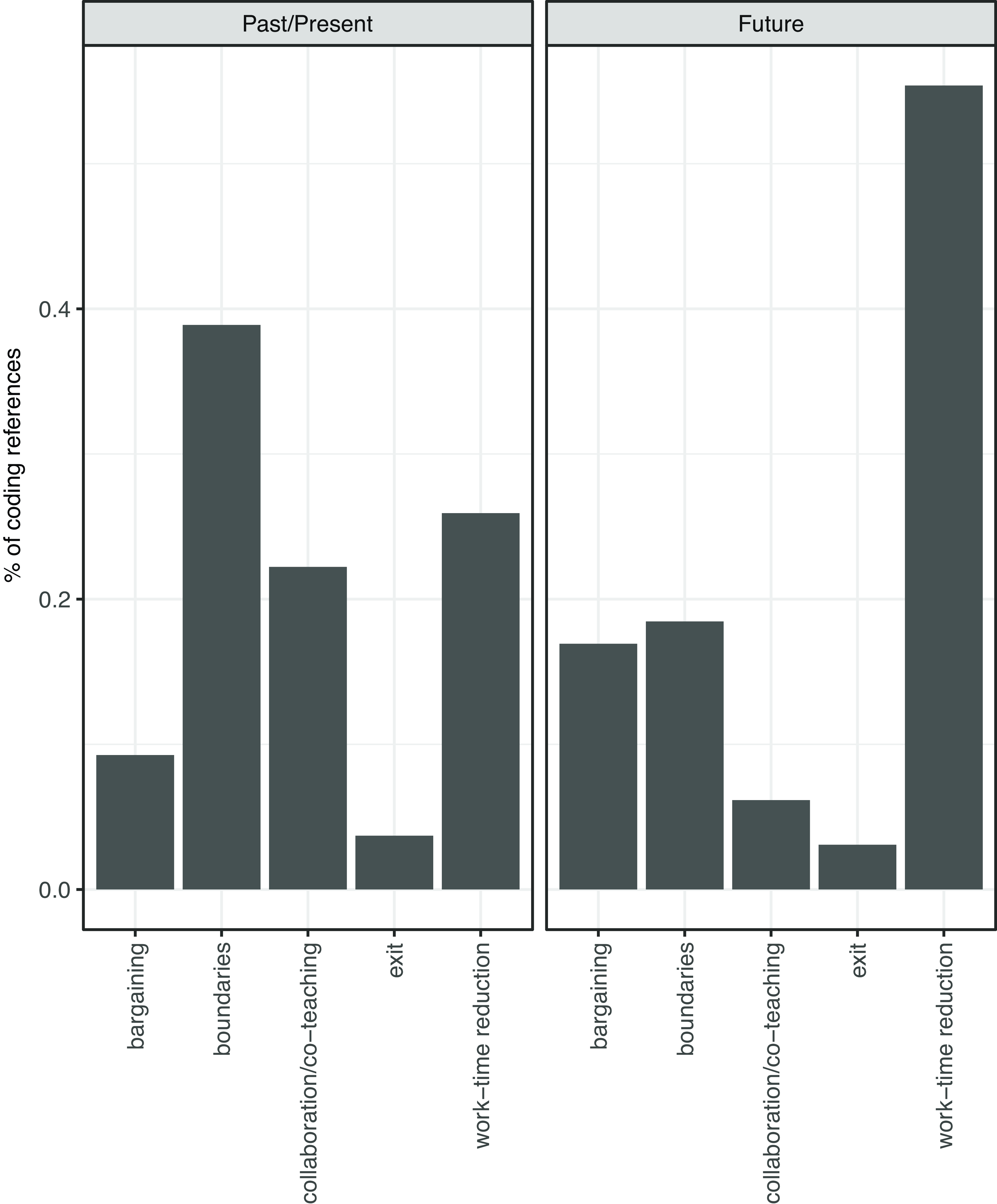

Figure 6 illustrates the frequency with which different strategies for managing teachers’ workload came up in our discussions. Work-time reductions were prompted by the discussion guide, but other strategies—such as bargaining for better contracts, setting boundaries and leaving the profession—were mentioned by participants without prompting by the facilitators.

Figure 6. Relative prominence of strategies for managing workload in focus group discussions.

While our participants had a high level of engagement with their unions and understood collective bargaining as an important way to improve their working conditions, much of the discussion of managing overwork still assumed that it was the responsibility of the individual. In other words, setting boundaries for oneself—by limiting how much work one takes home or by relaxing one’s very high standards for classroom preparation and teaching—was by far the most common strategy that teachers had been pursuing to manage their workloads. We interpret this to mean that while teachers know that their workload issues are widely shared, unless they are actively involved in contract negotiations, they typically approach the problem as something they have to solve on their own. Interestingly, a 2024 cover page article titled ‘The time crunch’ in the National Education Association’s newsletter, NEA Today, listed five individual strategies for teachers to ‘make more time’ and only three strategies for teachers’ unions’ collective bargaining and advocacy (Flaherty Reference Flaherty2024).

Since the return to in-person education, teachers have had to establish limits and boundaries around their availability to students after regular hours. Many teachers mentioned removing their work email accounts from their cell phones, or other ways to ‘unplug’ from school. Limiting communication with colleagues, supervisors, students and their parents after hours appears to be an important boundary-setting strategy. This finding points to the usefulness of raising awareness—and perhaps contractual language— about the ‘right to disconnect’ that has been won by labour unions in various countries in Europe and Latin America, as well as recently in Australia (de Luca Tamajo Reference De Luca Tamajo2024).

While many teachers had already begun pursuing individual strategies of setting boundaries, they typically did not find these solutions easy or satisfying. Because teachers are under pressure from supervisors and have very high expectations for themselves, they struggle with their own decisions to set limits. In other words, for many teachers, setting boundaries comes at a high emotional cost:

It’s disheartening in two ways. Because on one hand, you feel like you have no time, or you could keep working forever, and you have no time for yourself. And at the same time, it’s disheartening, because even if you did that, even if you gave up all your time, you’d still never be done with the job ’cause there is always more that you could be doing and maybe should be doing. So at some point you have to make that judgment call: quality of life or feeling like you’re doing everything you need to be doing. You… can’t quite do both (Jillian, elementary school).

Whether teachers decide to spend excessively long hours teaching or set limits on their hours of non-contracted work, they find that they must make difficult decisions with regards to how they allocate their time. Participants expressed disappointment with these trade-offs and the desire to be able to feel that they had done their best, both at school and at home.

When setting boundaries proves to be difficult or impossible, this brings up difficult emotions and frustrations. Because the concept of ‘work-life balance’ has been framed as a personal responsibility, teachers often feel like their difficulty in achieving this normative ideal is a personal failing:

I never am caught up…. I try not to take anything home, especially after the pandemic, because we work so hard and have tried to do so much. And it was just exhausting. So I would say for me, work-life balance—I try. [I always give my students feedback,] even if it’s not up to [the standards of] what I would love to do in a perfect world (Deborah, high school).

Even though Deborah was very clear in her assessment that she and her colleagues went above and beyond during the pandemic, her disappointment in not being able to achieve a true work-life balance due to her workload left her feeling perpetually in a difficult situation. Teachers also expressed how feelings of guilt for not being able to meet their high standards caused them to do more work. Several teachers mentioned feeling guilty if they do not put in additional hours working at home, as it means that students get less feedback or support. Discussions of guilt over not working more at home demonstrate how emotionally complex these decisions are at the individual level.

While teachers expressed guilt about setting boundaries, they also drew connections between their own well-being and their ability to teach. Teachers recognised that setting boundaries could lead to better self-care, which would in turn result in better teaching. Carrie (elementary school) described the benefit of prioritising taking time to exercise regularly:

I’ve realized that I feel much better when I do work out. I’m not as tired, I have more energy, more patience dealing with the kids all day, and it’s just a better place to be. I had to think about it: would I rather be in a better mental space dealing with my students all day or have a stack of papers corrected [but] be exhausted and not physically or mentally well? It’s hard because, as teachers, we’re perfectionists… So, for me, it was letting go of a lot of those things to take back my quality of life.

The identity of being a perfectionist, which came up frequently, opens up both the difficulty of setting boundaries as well as the motivation for it. Whereas excessively long hours may help teachers complete more necessary tasks and feel more prepared, taking time away from work helps them rest and rejuvenate, which can also improve their ability to teach and relate to their students (Hunter Gibney et al Reference Hunter Gibney, West, Gershenson, Hamermesh and Polachek2022). This could be a powerful way to build the political will for policies that improve the teaching profession by addressing overwork and reducing their workloads. In many ways, it is compatible with the concept of ‘bargaining for the common good’—a labour strategy that has been pursued in recent years.Footnote 12

Discussion: teachers’ perceptions of work-time reductions

Responses to our hypothetical question about a work-time reduction without loss of pay were mixed. Some teachers found the idea very attractive and expressed unqualified enthusiasm. Other teachers expressed more reservations or concerns, especially about implementation and effect on the quality of education.

Some participants were extremely enthusiastic. Ideas of how to use the hypothetical extra time included travel, museums, cooking and self-care—noting that this would improve teaching. Being able to take better care of oneself was associated with being able to take better care of their students. The enthusiasm for the work-time reductions without a loss of pay was shared by Jillian (elementary school). Like other teachers, she fantasised about using hypothetical extra time to catch up on work as well as do self-care activities:

You could just sign me up right now: I would take that [contract]… I think my teaching would improve because I’d be able to do those things like send those newsletters and those happy notes home to parents that I just don’t have time for now. I also think my health would improve, because I’d have time to cook meals and exercise and important things like that…

The connection between teachers’ desire to improve upon their teaching as well as their desire to improve their own lives was very strong. The belief that poor work-life balance has deleterious effects on teachers and therefore also their students is supported by the literature (Hunter Gibney et al Reference Hunter Gibney, West, Gershenson, Hamermesh and Polachek2022).

The connection between reduced working hours and family life was clear to many of the teachers. Tara (elementary school) hypothesised that work-time reductions without loss of pay would be especially appealing to people with young children:

When my kids were younger, [work-time reduction] definitely would have appealed to me… Maybe if your kids were older, I don’t know [how appealing it would be], but I would think I would do it if my kids were younger.

We share Tara’s hypothesis that work-time reductions based on a vision of job sharing would be especially appealing to parents of young children or other teachers with more intensive caregiving responsibilities. However, our focus groups contained very few parents of young children, so we are unable to verify this claim.Footnote 13

The imagined use of additional ‘free time’ to complete more teaching work

When prompted to think about a work-time reduction without a loss of pay, several teachers described wanting to use these additional hours to complete more schoolwork. Grading, preparing for lessons and communicating with families were among the topics that came up frequently. For some teachers, the hypothetical extra time was mostly spent completing schoolwork, while for others it included both catching up on work and personal time.

A major theme that emerged was that extra time could improve the quality of teaching, not only by allowing teachers to feel less stressed and time-constrained but also by giving them more time to complete work-related tasks. Teachers said that more time to prepare their classes and catch up on their work would be a boon for themselves and their students. Donna (high school) commented:

[With a work-time reduction,] I feel like I could do my job a lot better, and maybe would be less exhausted… maybe I can correct those papers over a couple hours and give them more attention than trying to speed through them in an hour and not give my best. But I feel like I could really do a better job and feel more adequate and have more balance with that. With those 8 hours I think that would be amazing.

Donna’s comment demonstrates that more time to prepare and catch up on work would affect not only her teaching but also her self-perception and feelings of well-being. According to one teacher, it is already a common practice for experienced teachers to take a personal day to catch up on grading or get ahead in planning. We believe that this demonstrates how prevalent and normalised overwork is among teachers. The fact that some teachers use their scarce personal days to catch up on grading or lesson preparation should be an issue that collective bargaining units take seriously.

Teachers’ values came through along with their focus on working more. The participants in our focus groups often described themselves as hard-working perfectionists, but they also valued other things, such as autonomy and creativity. For Alex (high school), the vision of a work-time reduction sounded like a promise of more autonomy over the workday, which was very appealing:

It would be so cool to have that control [over where and when to work] and just be trusted as a professional [to use the time how I see fit]… It would definitely encourage me to give faster feedback and more thorough feedback, and to go deeper in terms of the scope… It might also allow me to consider giving a different load of assignments, and …[change] how I assess students, or… give them the chance to revise their work.

While additional time spent giving students feedback factored heavily into Alex’s imagined use of additional time, the idea of being able to choose how to use the time was of great importance. This level of control and autonomy were equated as being treated as a professional. This comment piqued our interest because teachers are professionals and implied that their current working conditions do not treat them as such.

The prospect of improving the quality of teaching was also based on the ability of teachers to have the time and mental space to be creative. Lisa (high school) would use the extra time to improve her teaching, both by trying new and interesting tools and by developing her own materials. She said:

[If I was contracted for fewer hours,] I might actually have time to create some amazing lessons that … have been living in my head [but] that [I] don’t have time to get out.

Lisa also mentioned that with more time she would be able to use existing pedagogical tools, techniques and technologies that are new to her. She expressed interest in using these tools but doesn’t feel that she has the time to master them given her current workload.

Concerns about work-time reductions

The idea of implementing work-time reductions, given the high standards of education, was daunting for some teachers. Many teachers stated that curriculum standards have become too high and not age-appropriate, compared to earlier in their teaching careers. There was discussion of what parts of the curriculum would be affected and how it would or would not alter the expectations on individual teachers to implement, while also teaching remedial life skills. Tara (elementary school) stated:

They would definitely have to cut things out of the curriculum because I wouldn’t have time. I don’t even have time now to teach everything they want me to teach).

The idea of being contracted for fewer hours raised concerns about how a single teacher would be able to cover all the material that is required by the state.

Rebecca (middle school) was concerned that the mandatory curriculum and standards would make it impossible to reduce teachers’ work-time. Her solution was instead to change the curriculum standards, called the Massachusetts frameworks. As she said:

We all work what we work because that’s what the job requires of us to do… Unless you change the entire teaching profession, I don’t see how that’s gonna happen. Or [if you change] the [Massachusetts] frameworks—that would be lovely… Let’s cut that in half.

Rebecca stressed that the implementation of the plan would be key to whether or not it actually helped teachers reduce their workloads. Any change which required teachers to cover the same curriculum in less time sounded disastrous.

When prompted to think about job sharing as a way to meet existing curriculum standards, some teachers became more supportive of the idea, while others remained unsure. April (elementary school) voiced concerns about job sharing:

I think part of me would be super excited. I’d go home. But then another part of me is, oh, if you know my hours were shorter, somebody else was coming in then I would feel like, I almost need to communicate with that teacher in my free time to make sure [that the students were getting what they needed]… and it would almost be more [time consuming].

Thinking through the exact mechanisms of how work-time reductions might be accomplished was a useful exercise. Williamson et al (Reference Williamson, Cooper and Baird2015) found that while job sharing among teachers had benefits, it often resulted in unpaid overtime. While the teachers surveyed were generally satisfied with the flexibility that job sharing arrangements granted them, they also reported that communication and collaboration with one’s co-teacher often required additional unpaid hours in the evenings or on weekends (ibid). Contracts would have to be clearly specified to account for all the additional hours necessary for successful job sharing schemes.

Other ways to address the workload and reduce overwork

In response to the idea of work-time reduction as a way to improve the teaching profession and improve work–life balance, some teachers proposed alternatives for making contractual changes. The ideas favoured by some teachers included reducing the number of classes teachers are responsible for preparing, reducing the teacher–student ratio, reducing the hours of direct teacher–student instructional time and a longer winter break.

For many teachers, especially at the high school level, the main issue that they thought could be resolved was by reducing the number of individual classes that they were required to prepare and teach. Deborah (high school) explained:

[With fewer preps,] you can actually dive in, do a really good job. Feel like you can teach the curriculum and give the feedback, and then not be stressed… just give me less of a workload, and I’d be a happier teacher.

For Deborah and other teachers, fewer classes to prepare would be the most impactful way to streamline their duties, reduce their uncontracted work hours and improve their experience as an educator.

Other teachers stressed that reducing the number of students and the direct student instructional time for teachers would be the most impactful policy. Danielle (high school) said:

I can still work 40 hours a week. But reducing the teacher to student direct instruction time, I think, would have the biggest impact on my work-life balance.

This was often expressed with a tinge of regret, as teachers noted that they ‘love’ their students and spending time with them. Yet, reducing the number of students and time with students would allow them to make better use of the time they had. Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Camburn, Kelcey and Quintero2022) found that teacher–student interactions have a ‘protective role’ in helping teachers feel satisfaction with their jobs, yet teachers need sufficient supports—such as sufficient planning time —in order to derive positive experiences from their work with students (p.12).

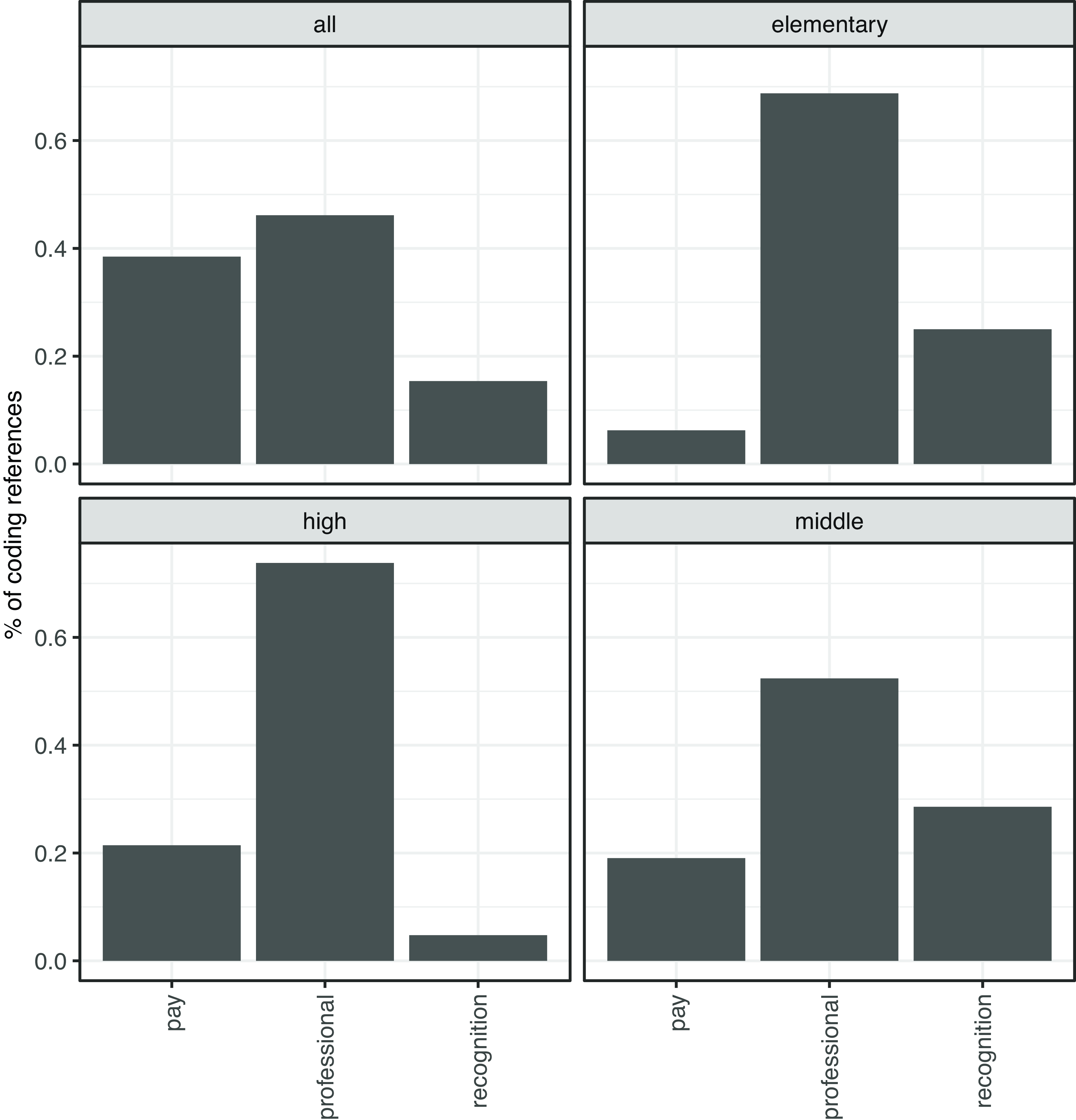

Fair wages for actual hours worked

Figure 7 shows how frequently different values and norms were mentioned in different focus groups. Most frequently mentioned across all groups were norms and values related to teachers’ professional identity, including caring for one’s students, being hard-working or a perfectionist and being a trained professional. The topics of pay and social recognition for their work also arose in all focus groups. Lisa (high school) said:

I do think we all need to be paid more… every single one of us, no matter where we live.

Figure 7. Relative prominence of values and norms in focus group discussions.

The implication was that teachers deserve higher pay, not only because of an increasingly high cost of living in Massachusetts but also because of the quality and quantity of the work that they do.

Some participants mentioned that, with a reduction in their work-time, they would be able to seek part-time work elsewhere, as a way to boost their overall earnings. This was true even for some teachers with two decades of teaching experience. Other participating teachers expressed that although they felt that their salaries afforded them an acceptable standard of living, they were not commensurate with the quality and quantity of work that they performed for their schools. Many felt that they and their colleagues deserve higher salaries not only because of the actual hours worked but also because of the ‘emotional labour’ that their job required. Alex (high school) commented:

[Even if my salary were doubled] it still wouldn’t account for a lot of the emotional labour or just the extra labour that doesn’t fit into [contracted] work hours. And … it would not be ludicrous… [If my salary were doubled, then one could say,] this person’s being paid… a fair wage for their labour.

Alex estimated that their salary was on the higher end for Massachusetts school teachers because they worked in an affluent and well-paying school district. This allowed Alex to purchase a home and not feel squeezed financially. Yet, the idea of fairness, both for quantity and quality of work, was paramount.

Several teachers referenced the concept of ‘emotional labour’—which was originally coined by Arlie Hochschild (Reference Hochschild1983) to describe the self-management of one’s emotions in the professional world. It has now entered the popular lexicon and experienced a definitional shift and is often used as a synonym for caring labour (Beck Reference Beck2018). Interestingly, the concept is used by teachers to explain why they deserve to be paid more, not less. Donna (high school) uses the phrase ‘emotional burdens’ to argue that she and her colleagues should get a fair wage:

We’re looking for a fair wage, not just more money. We’re looking for something that’s fair and reasonable, with all the amount of hours that we are putting in [and] the emotional burdens that we’re… taking on.

Fairness and recognition for the quantity and quality of labour was a recurring theme. In discussing pay raises and work-time reductions, several teachers also mentioned the discordance between teachers’ actual work-time and the public perception. Several teachers mentioned that there is an ‘illusion’ that teachers have a ‘cushy deal’ because they have shorter (contracted) hours and summers off. But they mentioned that in actuality, over the summer they work considerable hours preparing for the school year—typically spanning several weeks.

Discussion

Our conversations revealed some incongruence between teachers’ experience of overwork and their policy imaginations. While overwork was widespread, many teachers did not believe that they could obtain more leisure time through contract negotiations. We attribute this to several factors related to the teaching profession.

First, the idea of work-time reductions for teachers was sometimes interpreted as leading to reduced or reorganised instructional time for students, which is common with the ‘austerity approach’ to four-day school weeks. The austerity approach compromises curriculum standards and places major burdens on parents—including teachers who have young children. We share teachers’ concerns about the austerity version of work-time reductions. When facilitators reiterated the alternative vision of an ‘abundance approach’ to work-time reductions, teachers were more supportive. Yet, the austerity approach—and its risks—are more familiar to the teachers we interviewed. Doubts about the willingness to fund the abundance approach to work-time reductions were many, as teachers have experienced their school districts’ cutting funding, eliminating positions or requiring more work from teachers in exchange for meeting demands in contract negotiations.

The responsibilisation of teachers for student outcomes—instilled by increased surveillance, reporting and testing—occurs along with increased hours of work (Gavin et al Reference Gavin, McGrath-Champ, Wilson, Fitzgerald, Stacey, Riddle, Heffernan and Bright2022b). Together, these educational reforms create the ‘need for teachers to increasingly demonstrate and justify their work’ and likewise ‘can shape the subjectivity of teachers’ (Gavin et al Reference Gavin, McGrath-Champ, Wilson, Fitzgerald, Stacey, Riddle, Heffernan and Bright2022b 114). Given that education reforms in recent memory have been used to increase teachers’ responsibility for student outcomes and societal problems while simultaneously undermining autonomy and increasing surveillance and accountability measures, the idea that policy change could relieve some of this burden may seem far-fetched or impossible. Furthermore, the responsibilisation of teachers may be internalised, becoming part of teachers’ self-understanding of their professional roles (Stacey et al Reference Stacey, Wilson and McGrath-Champ2022)

The second limitation to teachers’ policy imagination with regard to increased leisure time related to their professional identities as care workers. One of our key findings of the focus groups was that when prompted to think about what teachers would do with an extra eight hours a week of ‘free time,’ many participants said that they would catch up on their grading, use the time to feel better prepared for their lessons, or communicate more with students’ families. While some teachers fantasised about using their time for leisure activities, cultural experiences, athletics or household tasks that they find enjoyable such as cooking, many others immediately thought about how their extra ‘free time’ could be used for teaching-related responsibilities such as lesson planning or student feedback.

Teachers repeatedly described themselves and their colleagues as ‘perfectionists’ and other phrases to denote that they are hard-working and willing to put in the extra time for their students. They described themselves and their colleagues in words that are typical of those in the caring professions, using words like ‘love’ to describe their commitment to educating their students. These self-perceptions may effectively hinder their efforts at improving their working conditions with respect to the length of the working day.

Drawing on the care work literature, we believe that teachers’ intrinsic motivation and internalised pressures may make it difficult for teachers to shorten their working day, either individually or collectively. Working in care professions generates caring attachments and preferences, reducing the willingness and ability of care professionals to threaten to withhold their labour to improve their working conditions (England Reference England2005). Individually, teachers face a type of coordination problem—if most other teachers are putting in long hours, then they will be compelled to do the same. Collectively, teachers may have difficulty organising around shorter hours if it is seen as a detriment to students’ learning.

Third, the discussion of increases in pay revealed the importance of the discrepancy in salaries among Massachusetts teachers. Some teachers reported needing additional income, whereas others felt that they should be paid more not because they were experiencing financial hardship at their current salary, but as a matter of principle given their work. We share the view that all Massachusetts teachers deserve higher salaries. What was interesting from these discussions was how frequently higher pay was understood around fairness and recognition. These are important values shared by the teachers in our focus groups which can be harnessed for organising efforts.

Our findings of incongruence between teachers’ experiences of overwork and policy imagination around work-time reduction is reflective of the ambivalence that many workers feel about their preferred working hours. Campbell and van Wanrooy (Reference Campbell and van Wanrooy2013) document through in-depth interviews a considerable extent of uncertainty around the desirability and feasibility of reducing work hours. Workers in their study, who were drawn from different professional and managerial occupations, saw long, effectively unpaid working hours as unavoidable. The authors summarize the attitude of these long-hour workers as one of ‘resignation’ and ‘fatalism’ (Campbell and van Wanrooy Reference Campbell and van Wanrooy2013 1150). Compared to these workers, the teachers in our study appear more willing to entertain hypothetical reductions in working hours, perhaps as a result of their involvement in collective bargaining.

Limitations

Our analysis is limited by several factors. First, we have a small sample. Of the 78,198 teachers in Massachusetts in 2023, we only spoke to 19. The goal of focus group research is not to systematically infer attributes of any population-level distribution, but instead to adequately sample the range of opinions and perceptions among a relatively homogenous group. The point at which further data collection does not yield substantively new opinions and perceptions is sometimes referred to as ‘saturation’ (Hennink Reference Hennink2014). While our results illustrate common patterns and beliefs, additional focus groups would be required to reach saturation.

Second, there may have been a selection bias with regard to the teachers who participated. In the focus groups, we noticed that many of the teachers were involved with their unions—currently serving on the collective bargaining team or having done so in the past. We hypothesise that the type of teacher who responded to our recruitment material—either on the email forwarded by the Massachusetts Teachers Association or on Facebook—may be more likely to be involved in union activity. This could potentially skew our sample in terms of political perspective or commitments. Exploring recruitment techniques that rely less on the formal and informal communications of teachers’ unions may yield different results and a wider array of perspectives.

Third, only one of our participants had small children at home. The time of our focus groups, in the evenings, is particularly difficult for parents of young children. We believe that the responses may have been different if we had participants who are parents of young children or who have intensive care responsibilities. How preferences and political commitments of teachers with young children compare to their colleagues with older children or no children is an open question that could be explored in future research. Exploring this empirical question for MA teachers could build on insights from Drago (Reference Drago2001).

Conclusions

Our analysis revealed widespread overwork as a normalised and disliked part of the job. Despite the common experience of an extensive and intensive working day, our conversations consisted of mixed reactions to the idea of work-time reductions without loss in pay. Teachers are experts in their own working conditions and their vision for improvement in the profession should guide any reform. While many teachers were enthusiastic about work-time reductions and job sharing, others were more cautious. Teachers stressed the necessity of well-specified contracts that protect preparation time, reduce the number of students and courses and give teachers more autonomy over curriculum.

This article has explored the desirability of a bold measure to make the teaching profession more attractive and improve learning and working conditions in public schools. If implemented appropriately, we believe such a work-time reduction could allow teachers, who often work significant unpaid hours outside the classroom, to rest, recover and enjoy leisure time. We believe that teachers deserve this. We also believe, as did many of our participants, that more time would allow teachers to be even more effective and compassionate educators, parents, caregivers and community members. As argued by Gavin et al (Reference Gavin, McGrath-Champ, Wilson, Fitzgerald, Stacey, Riddle, Heffernan and Bright2022b, 113), ‘Issues of teachers’ work and work-load are therefore central to the question of how schools can be for democracy’.

We envision schools as sites of plenitude—welcoming learning environments for students, attractive working environments for the teachers and educational support professionals and important anchors to the community. It should be noted that public schools already provide much more than simply childcare or education—they also provide food, counselling, healthcare and other essential services to children and adolescents—making them a bedrock of most US communities. We believe that the attendant changes in classroom organisation, staffing levels and working conditions would be manageable with sufficient financial support. Indeed, they would likely encourage the educational innovations and positive spillovers that are so frequently promised by more limited—and often less successful—attempts at school reform.

Public schools in the US are ripe for this kind of political and economic reform, as they represent one of the few sectors of the economy that has high union density and recent labour militancy (Blanc Reference Blanc2019). Furthermore, despite ongoing efforts to demonise teachers and make their curricula a centrepiece of regressive cultural politics, polls reveal that most Massachusetts residents support teachers and believe their right to strike should be legalised (Adame Reference Adame2024). The COVID-19 lockdowns, which required parents to supervise remote learning for months or years, re-established many parents’ perception of the enormous value of schools and a greater appreciation for the specialised professional skills of teachers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/elr.2025.16

Conflcits of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Katherine A. Moos is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a Research Associate at the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI). Her research interests include feminist political economy and the welfare state.

Noé M. Wiener is a Senior Lecturer of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a Research Associate at the Political Economy Research Institute. His research interests include the political economy of labour and economic methodology.