4.1 Introduction

Trade agreements create both ‘losers’ and ‘winners’, with the ability to benefit some and leave others without benefits or with negative ramifications. This is mainly because women and men play different roles and have varied access to opportunities in society, markets and the economy (Elson and Fontana Reference Elson and Fontana2018). It is therefore important that these trade policy instruments are negotiated with a gender lens to ensure that they can be used as a tool to minimize the negative impact and maximize the positive impact of international trade on women.Footnote 1

Various international organizations, think tanks and countries are now turning their focus on developing a better understanding of the trade and gender equality nexus and how gender equality can be integrated into countries’ trade policies. In 2017, 115 Members and Observers of the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreed to a joint declaration on enhancing women empowerment in international trade.Footnote 2 This was a landmark initiative by WTO Members in which they acknowledged the high degree of interconnectedness between trade and gender, and the need to have inclusive trade policies that are geared towards women empowerment. This development sits well with the objectives of the WTO, as the Marrakesh Agreement has pertinently included the objective of achieving sustainable development in its preamble (WTO 1994). The Addis Ababa Agenda of Action (Finance for Development 2015) also builds a clear network between international trade and gender equality as it reads as follows: ‘Recognizing the critical role of women as producers and traders, we will address their specific challenges in order to facilitate women’s equal and active participation in domestic, regional and international trade (UN 2015a).’

The UN General Assembly has called upon the WTO, the World Bank Group (WBG) and other international and regional bodies to support governmental initiatives and develop complementary programmes to help countries achieve full implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action to protect women’s rights (UN Women 2020). Moreover, the 2030 UN Agenda for Sustainable Development recognizes international trade as an engine for inclusive and sustainable economic growth, and an important means to achieve the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UN 2015b). These developments are aligned with and complement the other international legal instruments such as the UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) 1979.Footnote 3

Many existing trade agreements already contain provisions relating to gender equality that could provide a basis for translating into national trade policies to support women (Monteiro Reference Monteiro2018). Some of these provisions directly deal with empowering women as social actors or mothers such as ones on access to health care and maternity services and elimination of violence and discrimination based on sex (Hasham et al. Reference Hasham, Naliaka, Bahri, Pettinotti and Mendez Parra2022). Similarly, and in parallel, trade agreements, notably the Eurasian Economic Union Agreement (EAEU) and the EU-Central America Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), contain various provisions that seek to mitigate purely market-oriented and economic barriers that women face such as access to employment and finance, and access to information and to trade-related capacity-building programmes (Bahri Reference Bahri2021). These examples show that there are already several potential solutions included in the existing trade policy instruments that can help in ensuring that the opportunities offered by trade agreements are enjoyed equally by all including women.

As per the WTO’s database on gender provisions in preferential trade agreements (PTAs),Footnote 4 there are more than 300 provisions included in about 100 PTAs that are explicitly vocal about women’s interests or gender equality. This represents almost a third of PTAs currently in force and notified to the WTO by its members (WTO Gender Database 2022). Moreover, recent years have witnessed a sharp increase in the number of PTAs, mainly in the new-generation trade agreements, leading to the mainstreaming of concerns relating to women’s empowerment. These recent developments pose a challenge to the long-standing assumption that trade and gender are not interconnected, and on the contrary, they reflect that gender mainstreaming in trade agreements is here to stay. However, it is interesting to note that trade agreements have included these provisions in various different ways. Moreover, some countries have led the inclusion of these provisions in their trade agreements, and many others are yet to take their very first step in this direction. This chapter looks at variation in the degree to which countries have included gender provisions in their trade agreements, and with a special focus on the case of South America as various countries in this region have employed a number of innovative approaches to apply gender lens to their trade agreements.Footnote 5

The chapter’s first part looks at different approaches with which gender-related commitments are included by different regions in their trade agreements, through some interesting practice examples to show various differences and overlaps within the regions. The second part of this chapter zooms into one of these regions, that is, South America, as it has emerged as a frontrunner in drafting trade agreements with various different kinds of gender commitments and mainstreaming approaches. This segment provides reflection on the ways in which countries in South America have drafted gender provisions, the roles of women these provisions have focused on and the strategies of mainstreaming which are unique to this region (such as the inclusion of stand-alone chapters and the creation of dedicated implementation mechanisms).

4.2 Gender Mainstreaming in Trade Agreements: A Regional Comparison

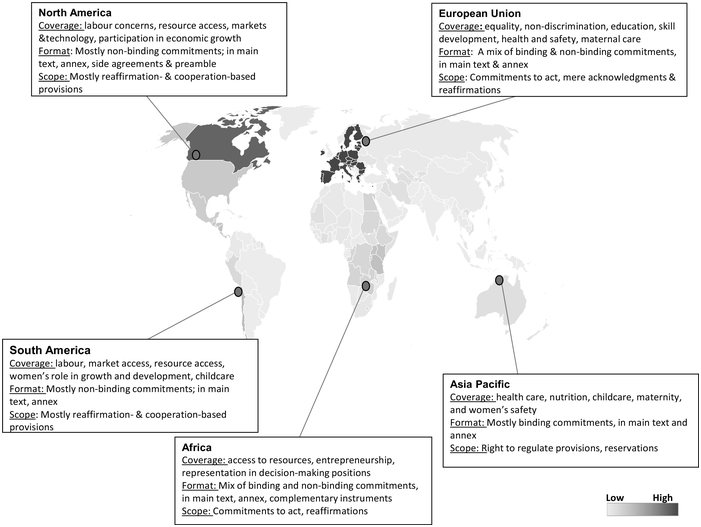

The focus areas covered by gender-related provisions in present-day trade agreements vary from one region to the other, ranging from an economic- and market-oriented focus, education and training, representation of women in decision-making roles, women’s employment status and labour conditions, female entrepreneurship, to purely social, maternity-related and healthcare concerns. Yet, there is some overlap. The following illustration underlines the most-commonly-used trends and focus areas in trade agreements negotiated by five different regions: North and South America, the European Union, Asia Pacific and Africa. These five regions are discussed in this chapter because, as seen in Figure 4.1 (Bahri Reference Bahri2021), these are the five major regions where countries have made some efforts in respect of negotiating their trade agreements with explicit gender commitments, and hence these regions have a story to be told.

Figure 4.1 Gender provisions in trade agreements: regional trends.

Notes: *The colour code reflects the aggregation of the number of times gender-explicit words are used in all existing FTAs signed by each country. The darker it is, the higher the frequency of gender-explicit words included in FTAs signed by that country; ** Only FTAs with explicit gender provisions were considered for the illustration. Some FTAs are included in the assessment of more than one country, depending upon the countries that are party to those agreements; *** Gender-explicit words used for listing products or entities are not included in this assessment; **** Only trade agreements notified to WTO and currently in force (as of 15 April 2022) are included in this assessment.

The illustration identifies countries that have led the inclusion of gender-explicit commitments in their trade agreements. The author is of the view that the content of gender provisions is much more relevant than the number of times gender-related words are mentioned in a specific agreement and a look at the number of times gender-explicit words are mentioned does not reveal the scope of commitments. Nevertheless, a mere look at the number of relevant words included in an agreement can provide an initial indication of whether a given trade agreement includes gender concerns and the extent to which these concerns are included. The underlying assumption is that the higher the usage of gender-explicit words, the higher is the number of legal provisions focused on gender concerns in a given agreement (Bahri Reference Bahri2021).

As seen in this illustration, gender mainstreaming in current trade agreements is quite heterogeneous as its approach differs from one region to the other. In the case of North America, the trade agreements signed by Canada, United States and Mexico (USMCA) have treated gender-related concerns from an economic and a market access perspective. A similar approach is observed in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) under Article 23.4. These provisions mainly focus on labour standards, women’s access to productive resources, markets and technology, skill development and their participation in economic growth. A leading recent example from this region is from the USMCA, whereby parties commit to enhancing trade and investment opportunities for small businesses, including those owned by women, as mentioned under Article 25.2 titled ‘Cooperation to increase trade and investment opportunities for SMEs’, and the agreement also includes improvement of labour standards such as elimination of discrimination, occupational safety, health and other workplace practices; the prevention of occupational injuries and illnesses; and the prevention of gender-based workplace violence and harassment listed under Article 23.12.2 (v).

The EU’s mainstreaming approach in some agreements such as the EU-Central America PTA and the EU-Albania PTA includes the above-mentioned issues, but this approach is more geared towards a wider range of concerns that deal with issues such as non-discrimination (pursuant to Article 24 in EU-Central America FTA), labour standards (under Article 13 in EU-Central America FTA), education and skill development (under Article 43 in EU-Central America FTA and Article 100 of EU-Albania PTA, respectively), health and safety (under Article 42 in EU-Central America FTA and Article 99 in EU-Albania PTA), and maternal care (under Article 44 of EU-Central America FTA). However, it is important to note that most of these agreements negotiated by the EU, strictly speaking, are broader than mere trade agreements as they are drafted as ‘Association Agreements’ (AAs), Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) or Strategic Partnership Agreements (SPAs). These broader agreements include several pillars that go beyond the trade regime and into areas such as politics, cooperation, immigration, social development, poverty and environment. Gender-relevant provisions in these agreements are generally included in the non-trade pillars such as the ones on cooperation and social development. Hence, there remains a question as to whether such inclusions can be seen ‘strictly speaking’ as gender mainstreaming efforts in trade policy context (Villup Reference Villup2015).

The EU has also taken the lead in respect of including gender-explicit provisions in its chapters or provisions on sustainable development in multiple PTAs. For example, chapter 9 in subsection IV in the EU-Armenia partnership agreements is titled ‘Trade and Sustainable Development’. It contains several provisions where parties seek to cooperate on activities to enhance sustainable development. The parties in this chapter in Article 272 ‘reaffirm their commitment to promote the development of international trade in such a way as to contribute to the objective of sustainable development, for the welfare of present and future generations’. The EU-Georgia Association Agreement has a stand-alone chapter 13 on trade and sustainable development. Parties in this chapter seek cooperation on various aspects, including labour, environment, human resource development and conservation of exhaustible resources such as forests and fisheries. The benefit of this approach is that it allows the parties to embrace various elements of sustainable development which may (or may not) include gender concerns and undertake commitment to work on different activities focused on environment, climate change, labour standards, poverty reduction and fight against corruption. The fundamental problem though with this approach is that because such chapters include a range of issues such as labour, child labour, environment, climate change, deforestation and human resource development, the focus on gender equality is included as ‘one’ of the concerns amongst many others. Often, such chapters therefore leave no room for inclusion of concrete commitments, activities and implementation machineries to achieve these varied goals.

Another contrast in gender mainstreaming approach can be seen in the topic areas covered by countries in the Asia Pacific. The PTAs’ gender provisions in this region mostly relate to women’s personal welfare concerns. Many of the inclusions in this region are drafted as ‘right to regulate’ provisions, wherein member countries reserve the policy space to regulate specific areas that may impact women’s health and maternal concerns, such as healthcare, nutrition, childcare and women’s personal safety (as seen in Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Agreement (ANZCERTA) under Annex II and Chile-South Korea Free Trade Agreement under Article 10.2). ANZCERTA, Annex II, for example, contains a reservation wherein New Zealand reserves the right to regulate certain social services including childcare. Childcare challenges pose a significant barrier to work, especially for mothers, who disproportionately take on unpaid responsibilities when they cannot find affordable childcare (Barnes Reference Barnes2015; Parker Reference Parker2015). Provision of affordable childcare facilities is therefore vital, as their absence limits women´s employment opportunities and educational aspirations.

Another example is the ASEAN-South Korea PTA, which focuses on women’s physical safety. Singapore (an ASEAN member state) reserves the right to regulate certain types of social services, including statutory supervision services related to the provision of accommodation for women and girls detained in a place of safety under Section 160 of the Singapore’s Women’s Charter (CPC 93312). In the New Zealand-South Korea FTA, parties reserve the right to regulate certain health and social services that relate to female professionals and women’s health interests. In its Annex II on Services and Investment, the parties reserve the right to adopt or maintain any measure with respect to maternity deliveries and related services, including services provided by midwives, and with respect to childcare. In the Korea-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (KSFTA), chapter 9 on cross-border trade-in services does not apply to subsidies or grants (including government-supported loans, guarantees and insurance) or social services provided in conjunction with childcare under Article 9.2.3 (d). Also, in chapter 10 on investment, parties reserve the right to regulate foreign investment in respect of childcare services under Article 10.2.5. This ‘right to regulate’ type of reservation helps to strike a balance between the protection of investment or trade liberalization on the one hand and the state’s policy space to regulate on issues such as national security, public health, environment and gender equality, among others (Gaukrodger Reference Gaukrodger2017).

The gender-explicit provisions found in PTAs signed by African countries seek primarily to integrate women into the region’s development process by enhancing women’s access to resources, promoting female entrepreneurship and increasing women’s representation and participation in political and decision-making positions. This can be seen in the Revised Treaty of Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) under Articles 3 and 63, and Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) under Articles 154 and 155. In the COMESA, for example, parties have assumed various commitments relating to gender equality. In chapter 24 of this agreement which focuses on women in development and business, the parties affirm that ‘women make significant contribution towards the process of socio-economic transformation and sustainable growth and that it is impossible to implement effective programmes for rural transformation and improvements in the informal sector without the full participation of women’. Through legislation and other measures, parties pledge to increase women’s participation in decision-making, eliminate regulations and customs that are discriminatory against women entrepreneurs and inhibit their access to resources, promote their education and awareness and adopt technology to support the professional progress of women. Similar commitments are seen in chapter 22 of the EAC, wherein countries seek to enhance women’s representation in socio-economic development, including their role in political bodies such as the East African Parliament listed under Article 121.

It is interesting to see that most of the gender-explicit provisions in the agreements negotiated by African countries, mainly East African countries, are drafted with affirmative and binding expressions (Laperele-Forget Reference Laperele-Forget2022). Moreover, some gender-related provisions are included in the ambit of the agreements’ dispute settlement mechanisms and are therefore enforceable and legally binding in nature. One such example is the Agreement on Trade Development and Cooperation between the EU and the Republic of South Africa. This is an interesting and unique best practice example, which differs from gender-related provisions drafted in best-endeavour language as is mostly visible in the case of PTAs negotiated by other regions as previously discussed.Footnote 6

Finally, there is another aspect of the South American approach that resembles that of North America but with some differentiating elements. Gender-related provisions negotiated by countries in that region focus on labour concerns, market and resource access, and women’s role in growth and development; though the agreements that South American countries have signed with Asian and Central American countries also include women’s personal welfare concerns (see, e.g., in the Chile-South Korea FTA, Article 10.2.4). Moreover, like in the case of North America, the provisions included in the agreements in this region are mostly drafted as best-endeavour cooperation-based provisions, without the use of any binding or enforceability-related expressions. Yet, this region stands apart due to certain features of its gender mainstreaming approach that distinguish this region from the others. One such feature includes reliance on stand-alone trade and gender chapters and the other could be its implementation-focused approach. The following section zooms into these distinguishing features and the overall gender mainstreaming approach employed by South American countries mainly in the new-generation trade agreements.

4.3 Zooming into the South American Approach

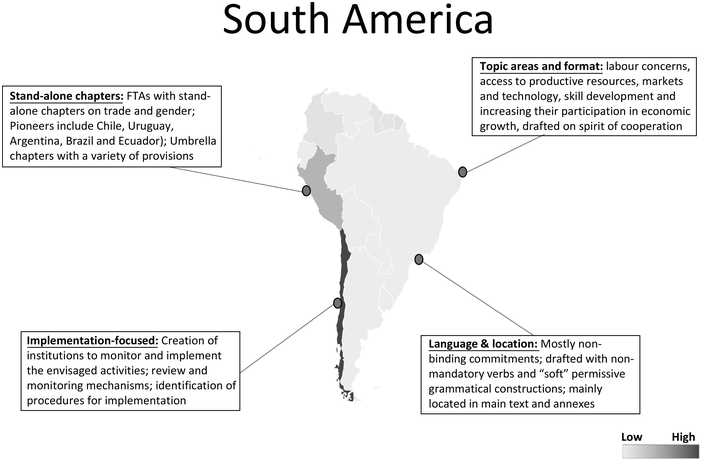

The South American countries have employed a number of mainstreaming trends for the negotiation and drafting of their trade agreements. This section will provide reflections on the four most distinguishing features of this approach. These features are explained in the following categories: (i) inclusion of stand-alone chapters on trade and gender; (ii) economic- and market-oriented focus areas, drafted in the spirit of cooperation; (iii) implementation-focused approach; and (iv) the language and location of relevant provisions (Bahri Reference Bahri2021) (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Zooming into the South American approach.

Notes: *The colour code reflects the aggregation of the number of times gender-explicit words are used in all existing PTAs signed by each country. The darker it is, the higher the frequency of gender-explicit words included in FTAs signed by that country; ** Only PTAs with explicit gender provisions were considered for the illustration. Some PTAs are included in the assessment of more than one country, depending upon the countries that are party to those agreements; *** Gender-explicit words used for listing products or entities are not included in this assessment; **** Only trade agreements notified to WTO and currently in force (as of 15 April 2022) are included in this assessment; *****The countries included in the South American region for the purposes of this assessment are Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay and Venezuela.

4.3.1 Inclusion of Stand-Alone Chapters on Trade and Gender

A best practice example that emerges from this region is the addition of a stand-alone trade and gender chapter. So far, out of nine countries that have signed PTAs with stand-alone chapters on trade and gender (i.e., Chile, Canada, Uruguay, Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Japan, the UK and Israel), five are from South America.Footnote 7 Chile has taken the lead and has included a stand-alone chapter on gender and trade in multiple PTAs (i.e., with Uruguay, Canada, Argentina, Brazil and Ecuador). Chile is also negotiating a gender chapter with Paraguay, and together with Colombia, Mexico and Peru, it is considering the inclusion of a gender chapter in the Agreement between the Pacific Alliance and Associates (Canada, New Zealand and Singapore).Footnote 8

An interesting recent development in this respect is the amended Chile-Ecuador trade agreement, which contains a new, dedicated chapter on trade and gender. Chapter 18 of this Agreement is quite comprehensive; as in other gender chapters negotiated by Chile, as it includes various affirmations, cooperation-based commitments and reaffirmations. However, it is the first of its kind as the parties to the agreement have created a detailed and dedicated bilateral consultation procedure to solve differences that may arise from the provisions included in this chapter. It is also the very first agreement that requires its parties to set up a national consultative committee that is responsible for gathering views from the public (including representatives from women’s organizations and business entities) on matters covered in the stand-alone gender chapter.

The EU and Chile are also negotiating a gender chapter for the modernized EU-Chile Association Agreement, wherein both countries have tabled their own draft chapter. If the EU’s proposed draft is included in the agreement, it will probably emerge as one of the most comprehensive chapters on trade and gender negotiated so far. Its scope is vast. Parties in this chapter reaffirm their commitment to gender-specific international conventions, such as CEDAW and International Labour Organization (ILO) Conventions. As a substantive obligation, they commit not to promote trade or investment opportunities by weakening or reducing the protection provided in domestic law and regulation relating to gender equality. They also commit to progressively eliminating discrimination against women in employment (Article 3.4 (b)); they also seek to work on various cooperation activities to enhance capacity and conditions of women not merely as employees but also as business leaders (Article 4.2); the agreement also allows parties to identify specific activities to work on connecting more women to the formal economy that includes work to increase women’s access to digital skills and online tools, decent quality jobs through trade, safety and health at work, flexible work conditions, affordable childcare, preparing girls for science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) careers and joint collection of sex-disaggregated data (Article 4.3). The text also contains a detailed bilateral consultation procedure to solve differences that may arise from the provisions included in this chapter (Article 6.3). Hence, this chapter goes beyond an attempt to merely insulate women from the possible negative impacts of trade liberalization or trade agreements; it seems more proactive as it can possibly increase women’s access to more trade opportunities and resources.

Inclusion of a dedicated chapter is a possible way forward to mainstream gender concerns in trade agreements as such a chapter can serve as an umbrella chapter for all kinds of provisions on gender, including cooperation activities, legal standards, affirmations and reaffirmations (Hughes Reference Hughes2019). This is comparatively a newer approach of gender mainstreaming; most of the existing agreements with such chapters were negotiated in the last six to seven years. However, it is important to mention that some earlier agreements (negotiated as regional integration agreements) by countries in Africa had started to include stand-alone chapters on women empowerment as early as the 1990s; in the year 1993, the 1993 treaty establishing the COMESA was negotiated as the first agreement in the world to feature that featured a stand-alone chapter on women in its main text (i.e., chapter 24, titled ‘Women in Development and Business’). Thereafter, it was replicated in 1999 as the treaty for the establishment of the East Africa Community (EAC), wherein countries also included a chapter on women in the year 1999 (i.e., chapter 22, titled ‘Enhancing the Role of Women in Socio-Economic Development’).

This approach does translate into something specific as it has four clear benefits: visibility, room for exploration, implementation machinery and capacity building. First, such chapters raise the profile of gender equality concerns in trade discourse and the visibility of gender considerations in trade policy instruments. Giving higher visibility to the ‘problem’ gender commitments can solve means trade negotiators and policymakers will have incentives to gain more awareness in this respect. It also helps negotiators justify the time and resources they spend on bilaterally negotiating these commitments with their counterparts.Footnote 9 Second, they justify the creation of institutions and mobilization of funds for putting gender commitments into action.Footnote 10 In the existing PTAs that have included a stand-alone chapter on gender and trade, parties have gone ahead to create a specialized committee or unit that will be responsible for implementing or overseeing the implementation of commitments contained in this umbrella chapter. As seen from the Canada-Chile FTA (CCFTA), Article N bis-04 titled ‘Trade and gender committee’ specifically details dedicated committees overseeing the work, providing advice and preparing reports, forming concrete action plans, and eventually tracking the progress of efforts and activities in respective countries. The Gender Committee created by Canada-Chile, for instance, has created a detailed workplace for implementation, with ten action items. For each action item, parties identify the objectives, implementation plan, expected results and action leads. These action items correspond to and mirror the provisions included in the gender chapter. Moreover, with a whole chapter to work on, the experts can likely engage in bilateral negotiations with dedicated counterparts on these issues, and this separate branch of negotiation can provide them legitimacy to mobilize funds for their meetings and activities.

The third benefit is that it gives parties much more room to include different, concrete commitments and also outline precise activities and procedures the specialized committees might work on and can employ to implement the commitments. It gives room to put in writing various ‘nuts and bolts’ including: what is the purpose of empowering women? What activities to engage in? Why can these activities help women? How exactly can the commitments be implemented or financed? And who might be responsible for their implementation or monitoring of implementation? The space for including different categories of provisions a chapter provides allows agreements to address these pertinent questions. These chapters may not resolve the deeply engrained social, cultural and legal barriers, but they can comprise provisions that may touch upon the barriers that impede women from accessing foreign trade opportunities and stimulate dialogue for their removal.Footnote 11 The fourth benefit is that such chapters can strengthen capacity building, especially when one of the countries is still in its early phases of understanding the interrelation between trade and gender. A specific chapter on gender will require (or at least motivate) countries negotiating that chapter to appoint dedicated negotiators with understanding of these issues to engage with their counterparts. This incentivizes countries to develop the capacity in this respect. A gender chapter can encourage appointment of expert officials for negotiation of gender and trade issues. Negotiators responsible for this chapter can have their own table to discuss, share their experiences, exchange best practices and understand better each other’s domestic conditions in this respect.Footnote 12

These benefits to some extent can also be realized with the inclusion of specific provisions on trade and gender, for example, in the case of CPTPP. Article 23.4 in CPTPP is a provision titled ‘Women and Economic Growth’. In this provision, parties ‘recognise that enhancing opportunities in their territories for women, including workers and business owners, to participate in the domestic and global economy contributes to economic development’. Parties under Article 19.10 and Article 21.2 also ‘consider undertaking cooperative activities aimed at enhancing the ability of women, including workers and business owners, to fully access and benefit from the opportunities created by this Agreement’. These activities touch upon and address the barriers discussed in chapter 1, but this approach does not allow the same room for exploring the inclusion of different kinds of provisions as a chapter would. It may also not have the similar kinds of capacity-building benefits discussed before.

4.3.2 Economic- and Market-Oriented Focus Areas, Drafted in the Spirit of Cooperation

The trade agreements signed by South American countries, mainly the new generation agreements, treat gender-related concerns primarily through an economic and market access perspective. The provisions in these agreements cover areas relating to women’s access to productive resources, markets and technology, skill development and increasing women’s participation in economic growth.

The modernized CCFTA trade accord presents an interesting example in this respect. This agreement has included a number of cooperation activities under Article N bis-03; these activities envision women as entrepreneurs, leaders, decision-makers and scientists. The activities envisaged by parties include focus on improving educational or skills development opportunities that can translate to high-paid job opportunities for women (such as STEM and information and communication technology (ICT)). This agreement is exceptional in this respect, as most trade pacts only consider cooperation focused on fields that have traditionally been reserved for women (such as farming, handicraft, textile and fisheries). Other activity areas it includes are promoting financial inclusion for women, including financial training, access to finance, and financial assistance; advancing women’s leadership and developing women’s networks in business and trade; fostering women’s representation in decision-making and positions of authority in the public and private sectors, including on corporate boards; promoting female entrepreneurship and women’s participation in international trade; conducting gender-based analysis; and sharing methods and procedures for the collection of sex-disaggregated data, the use of indicators and the analysis of gender-focused statistics related to trade. These new areas can enhance women’s access to productive resources and markets and enable women to move away from the traditional stereotypical jobs that the societies have imposed on them such as farming, nursing or household responsibilities.

Parties in the Chile-Uruguay Economic Agreement seek to focus on women as workers as well as entrepreneurs through its chapter 14 on trade and gender; they seek to also promote the development of skills and competencies of women in labour and business; to improve women’s access to technology, science and innovation; to promote financial women’s access to technology, science and innovation; to develop women’s leadership networks; to further the participation of women in decision-making positions in the public and private sectors and promote female entrepreneurship, and others as listed under Article 14.3. However, most of these cooperation-based commitments are drafted in best-endeavour language, and, hence, are not binding on the parties. Such best endeavours drafted with permissive expressions are also found in other trade agreements wherein South American countries have negotiated gender provisions such as in the Chile-Ecuador and Chile-Argentina trade agreements. Nevertheless, the value of aspirational provisions cannot be underrated, as these provisions can still change the normative environment of trade negotiations and can act as a starting point in negotiating gender-related commitments for countries with less developed appetite or understanding on these matters.

The countries in such cooperation-based provisions assume soft commitments, and they often contain a list of activities that parties seek to work on and also provide a list of affirmative statements recognising the problem. Countries in these provisions have also reaffirmed in such provisions their commitments under other international instruments, including the United Nations 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals; the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) 1979; the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights; the Beijing Declaration of 1995 and Platform for Action, as well as the ILO conventions that refer to women’s labour rights and the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. Even though these reaffirmations can send an important signal to the international community about the priorities of these countries, they are nevertheless reaffirmations where parties merely recall their already assumed commitments; these provisions do not identify or provide space for parties to undertake a specific positive action in respect of women empowerment.

One final observation to note in this regard is that the focus of gender provisions has changed when South American countries have negotiated agreements with Asian countries. The gender provisions in many of those agreements are drafted as binding right to regulate reservations upholding women’s role as mothers. For example, Article 10.2 of the Chile-South Korea FTA contains a right to regulate childcare services. A similar reservation can be found in the Annex II of the Peru-South Korea FTA. These reservations are drafted with binding expressions and language, making them legally enforceable in nature. They are worded as the right to regulate provisions, wherein countries reserve policy space to regulate specific areas that may affect women’s health and maternal concerns, such as health care, nutrition, childcare and women’s personal safety.

4.3.3 Implementation-Focused Approach

Despite the proliferation of gender-related provisions and chapters in the existing trade agreements, current approaches merely scratch the surface of what they can achieve in respect of empowering women. This is due to many reasons, but one of the major reasons is that the current gender provisions often fall short of providing a mechanism to implement and oversee the implementation of such commitments. Almost no PTA so far contemplates how gender-related commitments could be put into action. As of today, most of the PTAs that incorporate gender equality concerns do not clarify procedures for implementation, nor do they identify channels to finance these activities.Footnote 13 Countries have gone ahead to assume commitments, often without a single mention of which stakeholder or institution in their countries would be responsible for the implementation of the best-endeavour promises they load their gender-specific provisions or chapters with. Without such an implementation mechanism, it is difficult to see how gender-related commitments will translate into concrete actions. However, some countries in South America have carved out an exception to this rule in their agreements.

Some recent agreements have established specialized committees to oversee and monitor the implementation of gender-focused provisions and gender impact of trade. One example is the Chile-Uruguay FTA, which provides for the creation of a gender committee under Article 14.4. It provides that this committee is to be composed of representatives from the government institutions responsible for relevant gender and trade matters from each concerned party, but it falls short of prescribing its functions and operation requirements. The CCFTA raises the bar higher as it provides for some operational requirements and functions of the trade and gender committee under Article N bis-04. This Committee under both agreements is supposed to meet at least once a year, and it should review the implementation of the chapter after two years. The Agreements also provide for a mechanism for parties to engage in consultations to resolve disputes, as there are provisions under CCFTA Article N bis-05 and Chile-Uruguay FTA Article 14.5 that state that the contracting parties will make all necessary efforts to solve any issues that may arise regarding chapter’s application and interpretation, through consultations and dialogue. Similar provisions are also found in Chile-Argentina FTA (Article 15.5), Chile-Brazil FTA (Article 18.6) and Chile-Ecuador PTA (Article 18.8).

These attempts at creating institutions and procedures are worth applauding, but resources are needed to carry out these functions, and the required provisions often fall short of clarifying how these functions or activities or committee meetings might be financed. Moreover, in most of the attempts where countries have identified institutions and procedures for implementation, the agreements have fallen short of specifying various other aspects required for effective implementation of such provisions. This is because the existing provisions often do not clarify precise functions of such committees, the way the activities and meetings of these committees will be financed, the procedures they might employ in performing their functions, the timelines and action plans.

Overcoming this barrier to some extent, the Chile-Ecuador PTA not only defines contact points and their responsibilities, but it also provides for a dedicated bilateral consultation mechanism to solve differences that may arise from the provisions included in Article 18.7 in the stand-alone trade and gender. This process is based on a mutually acceptable resolution and is guided by established timelines for each step of the process. First, the affected party is required to present a request through contact points to solve the matter; if it is not solved, the request is then transferred to the specialized committee; and in case there is no resolution by this stage, it can be sent to the related government ministers. At any stage of this process, parties can use the good offices, and if an agreement is reached, the final report is to be publicly made available.

In line with these recent developments, it is important that future PTAs contemplate and clearly outline the functions of the committees, milestones and objectives it is expected to achieve, and a timeline by which it is expected to achieve these milestones. There should be clear provisions on how committee’s work will be monitored, and who will comprise these committees. The most important in this regard is providing for funding arrangements to finance the activities and functioning of such committees if we genuinely intend these committees to function. However, such an institutionalization may likely become quite burdensome for developing countries that may not have the required resources to provide for the same for every trade agreement they sign.

4.3.4 Language and Location of Relevant Provisions

With very few exceptions, most of the gender-related concerns included in the regions’ existing agreements are drafted with non-mandatory verbs and ‘soft’ grammatical constructions (Bhala and Wood Reference Bhala and Wood2019). This soft nature of these provisions implies that compliance with them is completely voluntary, and non-compliance does not attract any consequence. The provisions on cooperation have another problem: most of these provisions in South American PTAs have left their implementation to the willingness and available resources that the concerned parties may have. For example, CCFTA Article N bis-03.6 explicitly states that the ‘priorities for cooperation activities shall be decided by the parties based on their interests and available resources’. The countries have generally left the implementation of these activities to their available resources and willingness, because they are probably not ready to undertake these commitments as binding and enforceable.

This is not unique to this region only, as even in other areas with very few exceptions, gender mainstreaming approach so far has been rooted in the spirit of cooperation wherein parties seek to use cooperation as a route to start this dialogue with others, as seen in the EU-Central America Agreement (Article 24.1). Moreover, such provisions list their benefits, as the value of aspirational and/or vague provisions cannot be underrated. These provisions can still change the normative environment of trade negotiations and serve as a starting point in negotiating gender-related commitments for countries with less developed appetites or understanding on how trade and gender relate to each other. This is mainly because countries sometimes need some flexibility in assuming commitments that they do not entirely understand the implications for and before using trade agreements to protect women when they do not know how the agreements will affect the women in their jurisdictions. To better establish this nexus between trade and gender and have evidence for policymakers, more gender-disaggregated data is required on this subject (UNECE 2021 and Peltola and MacFeely Reference Peltola and MacFeely2019).

In terms of the location of these provisions in trade agreements signed by South American countries, gender-related provisions have mostly appeared in the agreements’ main text. Only occasionally, they are added in a side agreement or in an annex as seen in Peru-South Korea FTA. In the main text, the gender-explicit provisions have most commonly been loaded in agreement’s provisions on cooperation or development. For instance, the Chile-Vietnam FTA proposes gender as one of the spheres of cooperation under Article 9.3 within its cooperation chapter, and the Peru-Australia FTA (PAFTA) refers to women and economic growth under Article 22.4 within its development chapter. In this provision titled ‘Women and Economic Growth’, the contracting parties have recognized the importance of enhancing opportunities for women so as to contribute to economic development, for which it promotes cooperation activities that aim at enhancing the ability of women to fully access and benefit from the opportunities created by the agreement.

Another recent development of this nature is the Global Trade and Gender Arrangement, signed in August 2020 between Canada, Chile and New Zealand (and Mexico in 2021). This is an independent instrument not annexed to any particular agreement. Through this, parties impose commitments on their respective governments as well as on the business stakeholders. In trade-in services under Section 4, the parties undertake to ensure that no sex-based discrimination is made in measures relating to licensing requirements and procedures, qualification requirements and procedures, or technical standards relating to authorization for the supply of a service. In this Arrangement, each party encourages ‘enterprises operating within its territory or subject to its jurisdiction to voluntarily incorporate into their internal policies those internationally recognised standards, guidelines and principles that address gender equality that have been endorsed or are supported’ by that member state under Section 5. Parties also identify a wide range of cooperation activities to enhance the ‘ability of women, including workers, entrepreneurs, businesswomen and business owners, to fully access and benefit from the opportunities created by this Arrangement’ under Section 8(b). However, what is not clear is the kind of opportunities the parties are referring to here, as the Arrangement is neither an understanding on trade agreement nor attached to any other trade agreement that may be seen as creating trade opportunities for women in these economies.

4.4 Final Thoughts

Through gender mainstreaming, FTAs can help reduce the formidable barriers that impede women’s participation in the economy. Using such inclusions, countries can bind themselves to certain minimum legal standards for improving the employment conditions for women or prohibiting sex-based discrimination. Countries can also endeavour to increase women’s access to health services, education and skill development. They can also create encouraging conditions for women businesses to flourish, for example by the creation of business networks and improved infrastructure in relevant sectors and industries. Countries in PTAs could also commit to increasing the representation of women in decision-making and policy-making roles. Moreover, trade-in services being an important area for women in a number of South American countries such as Chile, PTAs should go beyond their current scope to include provisions on enhancing women’s participation in services sectors of these countries. The baseline is thus: countries can use trade agreements as laboratories where they can experiment with different legal provisions and commitments regarding gender equality. However, there is a half-opened door in PTAs that countries need to push upon further by finding different ways of implementing or enforcing their gender-related commitments.

Some recent agreements signed by South American countries have taken the next step to push open this door further, but more needs to be done in this respect. Almost no PTA in the region so far contemplates how gender-related commitments could be legally enforced, and most of the gender equality considerations included in the existing agreements are drafted with non-mandatory verbs and ‘soft’ permissive grammatical constructions.Footnote 14 As of today, even the most advanced PTAs in respect of gender equality concerns have not identified channels to finance these much-promised actions. To ensure that trade agreements and policies work to create an inclusive trading environment, they need to be drafted with a gender-responsive approach; a gender-responsive approach calls for the inclusion of gender-related provisions that are not merely best-endeavour promises but are also enforceable, implementable and effective in nature.

It is expected that the ongoing trade negotiations on several PTAs in the region (which include Canada-Mercosur, Pacific Alliance, Chile-European Union and Chile-Paraguay) will take a step further and include trade and gender issues in a more concrete and unambiguous manner. As these negotiations are still in process, it is not possible to make an assumption about the ways in which they will include commitments on gender issues, but empirical research shows that the negotiators of these policy instruments are considering various options for making these instruments work for everyone, including women. The discussions in this chapter have shown that there is clearly a strong political will and expertise in the region in the area of trade and gender, yet the question remains as to whether we will see these future trade agreements take the next step in this direction.

A significant part of future trade policy-making in this respect would also depend upon the trade partners these countries engage with, as countries in this region may be able to assume more proactive commitments if they negotiate with countries that are also willing to accept gender-related commitments, are like minded or are similarly situated in terms of gender development levels (which for example could be measured by gender development index) (Monteiro Reference Monteiro2021). Having trade partners with similar domestic conditions minimizes the fears of associated fears and provides a larger zone of confidence to deal with domestic yet culturally sensitive matters such as this. Moreover, some countries may not have the required capacity to understand the inter-relationship between trade, investment and gender; gather concrete gender-disaggregated data to disentangle the impact of trade and investment on gender roles; and negotiate such provisions with their trade partners, while others may have a more nuanced approach and experience of negotiating such provisions.Footnote 15