Is Meta a more decentralized organization today than twenty years ago, when it was known as “Thefacebook”? Its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, certainly delegates a wider range of tasks to a wider range of intermediaries in 2024 compared to 2004. But Meta is also a far larger company today. Two decades ago, it was a small start-up; today, it is a multinational, publicly listed company. Given this organizational transformation, it would be odd to describe Meta as more decentralized today than “Thefacebook” twenty years ago without accounting for scale or giving more context. It is similarly odd when historians describe the Ottoman state as being more decentralized in the 18th century than in the 16th century.Footnote 1

In this review essay I explain why. I suggest several interrelated reasons: the neglect of scale, the misidentification of Ottoman imperial territory for the Ottoman state, the assumption that proliferating intermediaries indicated a weakening of central imperial control, and the tendency to evaluate governance decisions by whether they were made centrally or provincially, and not by their actual outcomes (in part because there is no agreed upon method to assess these outcomes).

I propose a different way of understanding the Ottoman state and its transformation. First, it is the Ottoman imperial bureaucracy, not its territory, that should be defined as the state and the appropriate unit of analysis. According to longstanding secondary scholarship, the Ottoman state expanded in scale (in numbers of personnel, in documentation produced) significantly after the 16th century. Defining the Ottoman state as the imperial bureaucracy clarifies downstream research questions that must be asked, such as how did an expanded Ottoman state organize its newly recruited intermediaries, and did they achieve the intended outcomes?

This definition shifts focus to the role of intermediaries. To be a preindustrial empire is to necessarily rule indirectly by delegating tasks and empowering local intermediaries with the authority to make decisions.Footnote 2 Recognizing the banality of task delegation allows historians to distinguish business as usual in large organizations from extraordinary periods of disorder, social collapse, and genuine loss of central control. Conflict between principal and agent was a feature, not a bug, of large imperial bureaucracies with far-flung provinces. What we historians know today about this principal-agent dynamic (between central and provincial administrators) was captured on slow-moving paper in an era where information flows were still embodied and could only travel as fast as a courier on a horse. Local officials’ autonomy in managing local affairs was, in fact, a default condition given their distance from the imperial capital. This default condition of local autonomy should not always be conflated with loss of central control.

In practice, distinguishing mundane bureaucratic friction from extraordinary crisis is a thorny challenge for historians, especially when considering the heterogeneous Ottoman provinces, each with different politico-fiscal agreements with the imperial administration.Footnote 3 I suggest that refocusing analysis on the intermediaries involved in Ottoman governance can clarify how Ottoman state formation processes changed. This call to focus on intermediaries is not new; historians have long focused on intermediaries, defining them as a range of contractors, local notables, functionaries, officials, corporations, councils, assemblies, and tax farmers.Footnote 4 But what is new, perhaps, is the push to taxonomize these proliferating intermediaries and to clarify their roles in the context of an expanding state--this clarification can, in turn, produce a clearer view of governance outcomes. What is also new here is recognizing the expansion of the Ottoman state as an axiomatic starting point. In sum, this attempt to taxonomize should not be controversial; it is a similar methodological move to categorizing Ottoman territories according to their politico-fiscal relationship to the state (i.e., “core” timar territories, semi-autonomous salyaneli territories, and vassal-like tributary territories).Footnote 5

The question at the heart of this review essay – what the macro, long-term trends of Ottoman state formation were – lends itself to social science methods. To that end, the essay ends with two possible social science approaches to carrying out the taxonomy and analysis of Ottoman intermediaries described above. These are not the only two possible approaches; they are just the two I could think of. This essay’s main aim is not to dogmatically champion specific scholarly approaches, but rather to open a conversation that can move the field beyond the defunct de/centralization paradigm.

An Impasse in Ottoman Historiography

Today, Ottoman historiography is still largely governed by a paradigm that sees the empire as having a “precocious” centralized state in the 15th and 16th centuries, a “privatizing” decentralized state in the 18th century, and finally, a “modernizing” centralized state in the 19th century.Footnote 6 This tripartite de/centralization schema likely arose from the uneven development of 20th-century Ottoman historiography. By the 1970s, scholars observed that Ottoman research tended to cluster around the “golden age” of the 16th century or the “modernizing” 19th century, contributing to “two disjointed temporalities of the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries.”Footnote 7 These uneven research foci neglected the “middle period” between the empire’s founding and its modernization, likely encouraging historians of an earlier generation to view the empire as entering a centuries-long period of decline after the 16th century.Footnote 8

In the 1990s, a new generation of scholarly studies focused on the 18th century rebalanced this uneven historiography. New literature on Ottoman fiscal practices, especially the life-term tax grant (malikane), helped to reframe the 18th-century period as an era of “decentralization.”

At the time, the “decentralization” concept was greeted with skepticism in some quarters. Some historians argued that it was really a “euphemism” for the other “d-word”: decline. Others critiqued the “inherent negativity” of the concept, which, they alleged, overshadowed the fact that the Ottoman bureaucracy remained “viable” until the 1800s.Footnote 9 Still others offered alternatives, such as “consolidation” and “transformation,” the latter of which has recently been critiqued as an imprecise, “catch-all” term.Footnote 10

In a way, “centralization” and “decentralization” have become “catch-all” terms as well; they are frequently invoked but often left undefined. Notably, historians have used this language of de/centralization (“centrifugal,” “centripetal decentralization,” “decentralizing centralists”) to describe the Ottoman state and its processes in the 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.Footnote 11 This is a long time to have analytical purchase.

In cases where these terms are defined, historians use them to refer to quite different phenomena. For instance, historians can use “centralization” to refer to: a state that is autonomous from the ruling class; the Ottomanization of provinces through, for instance, the codification of provincial law codes (liva or sancak kanunnameleri);Footnote 12 direct appointments by the imperial bureaucracy, such as appointing a judge or janissaries in the provinces (as opposed to local appointments of officials, such as the postmaster);Footnote 13 the application of the timar land-grant system, which, in the view of some historians, distinguished core, central lands from non-core regions;Footnote 14 and the quality of sultanic leadership.Footnote 15 Other times, historians use “centralization” to mean standardization (such as the adoption of European mean time across the empire), the uniformization of administrative processes, or the state’s new involvement in areas in which it previously did not intervene.Footnote 16

Historians have used “decentralization” to refer to the formation of provincial networks of elites, whether they were openly rebellious or obedient to imperial directives, and even when they enjoyed close relations with the imperial administration in the capital and with the sultan.Footnote 17 “Decentralization” has also been used to refer to the granting of life-term tax farming contracts (malikane) across the empire;Footnote 18 the growing economic independence of certain cities, such as Smyrna, as they integrated into the world economy;Footnote 19 the decrease in tax revenues accruing to the Imperial Treasury;Footnote 20 the “abandonment of provincial regulations” (whose enforcement in previous centuries, in any case, was never clear); and to describe the onset of intra-elite struggles resulting from the shift in the locus of power from the House of Osman to an elite circle of powerful households (from the monarch to the monarchy), a process some have named the Second Ottoman Empire.Footnote 21

Regardless of one’s thoughts on the utility of the de/centralization paradigm, hopefully historians can agree at least that this semantic expansion comes at the expense of analytical precision. Worryingly, this semantic confusion, together with the lack of feasible alternatives, threatens to revive already refuted paradigms of Ottoman history. Recently published monographs continue to state, matter-of-factly, that the 16th century was a period when “centralized power was at its height” and, subsequently, that “decentralized governance replaced the strong centralist pull” of the 16th century.Footnote 22 The notion of “centralized power” being “at its height” in the 16th century has roots in older romantic visions of a Suleymanic golden age. This Suleymanic golden age, in turn, is a crucial element in the decline paradigm that states that the Ottoman Empire entered a long period of decay and corruption after Suleyman’s reign ended in 1566.Footnote 23 The germ of the decline paradigm has endured, refusing to die – a germ incubated in its euphemism, decentralization.Footnote 24

The Problem of Scale

There is a territory-bureaucracy fallacy at the heart of the de/centralization discourse.Footnote 25 The expansion or contraction of imperial territory is distinct from the transformation of the imperial bureaucracy governing that territory; it is possible for the imperial territory to have shrunk at the same time as the bureaucracy expanded. The imperial bureaucracy should thus be defined as the Ottoman state and is the appropriate unit of analysis. It is the changing scale of the state – not its territory – that determined the reach, scope, and weight (or impact) of Ottoman rule between the 16th and 19th centuries.Footnote 26

Secondary literature on Ottoman history is clear that the 18th-century Ottoman state was much larger than its 16th-century incarnation in terms of both personnel and how much more documentation it produced than the two previous centuries. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, the number of scribes in the Ottoman imperial bureaucracy increased from 50 clerks and 23 apprentices to between 50,000 and 100,000 men.Footnote 27 During this same time period, new bureaus emerged and produced new genres of administrative documents, such as the Office of Protocols (Teşrifat Kalemi), the Protocol Register (Teşrifat Defteri), the Post Station Bureau (Menzil Kalemi), and a range of post station-related registers (Menzil Defteri, Inamat Defteri, and others).Footnote 28

The increasing specialization of some genres of administrative documents mirrored, to an extent, the increasing specialization of new bureaus in the imperial bureaucracy. In 1649, for instance, the Complaints Register (Şikayet Defteri) was hived off from the Register of Important Affairs (Mühimme Defteri) to become an autonomous register; and in 1752, the Complaints Register underwent further specialization as Provincial Complaints Registers were created to cater to each province in the empire.Footnote 29 Another example is the separation of “codes of law” and “codes of protocol” (Teşrifat Kanunnamesi).Footnote 30 Historians have described this phenomenon as the “specialization” of the “provincial paper trail,” of diplomatic and state protocol, and more generally, of bureaucratic documentation.Footnote 31 The overall picture is one of an expanding group of administrators organized into more specialized bureaus producing more specialized administrative documents.

Available evidence on urbanization trends in Anatolia match this timeline: between the 16th and 18th centuries, secondary towns grew “in number and influence,” suggesting a correlation between urbanization (and possibly, demography) and the growing specialization and intensity of provincial administration.Footnote 32

An expanded state did not mean a better or more efficient state. More personnel and more documentation did not mean better or more efficient outcomes.Footnote 33 My argument here is thus a narrow one: there was an expansion in organizational scale, there was increased activity, there was increased scope, but I make no claim about increased effectiveness or the quality of outcomes.

More Intermediaries did not Necessarily Mean Weakening Imperial Control

The mere existence of more intermediaries did not, in and of itself, indicate weakening imperial control. Historians cannot assume imperial weakness based solely on the proliferation of intermediaries – they have to show how this weakness came about. Even if we know that, ultimately, the Ottoman Empire broke apart, the particular way in which it collapsed requires analysis. Recognizing the contingency of the shape of Ottoman collapse – and the fact that proliferating intermediaries can produce a variety of outcomes, negative and positive – is historical work.

To be a large empire is to necessarily depend on intermediaries to govern. This is especially true for the pre-industrial period, when communication and transportation over large distances were slow and costly. This dependence on intermediaries and chains of intermediaries means that control necessarily meant indirect control, not direct; it also means that so-called “centralized” empires would have depended predominantly on intermediaries and exercised indirect control in many arenas of governance in the pre-industrial world.Footnote 34

In theory, an organization can be centralized and brittle, or decentralized and powerful. Centralizing all decision-making in one individual authority creates a single point of failure, which is a huge vulnerability; if that individual authority is disabled, the entire organization can become paralyzed. Conversely, decentralizing decision-making under multiple authorities can ensure resilience and responsiveness in times of crisis, but it can also be difficult to gain consensus and unify these different powerbases. It all depends on the working relations among the different authorities, their experience collaborating and coordinating with each other, the political culture, and a host of other factors. In between these two poles are many possible ways of calibrating the trade-offs among centralized decision-making structures, flexibility, and security.

The quintessential example of state centralization within Ottoman historiography is the 19th-century Tanzimat reform period (1840–76). Specifically, there is a broadly accepted idea that, in this period, tax collection came under the state’s “direct control.”Footnote 35 Yet, even in this classic example of “centralization,” intermediaries were involved: new tax collectors (muhassıls) replaced an older group of intermediaries. These new intermediaries also took time to learn the ropes of tax collection – in fact, collected tax revenues had decreased initially, compared to pre-Tanzimat times.Footnote 36 When collected tax revenues did eventually increase, the question historians could ask is: what made this new set of intermediaries more effective than the previous? Locally appointed intermediaries might be more prone to pursuing local interests at the expense of imperial ones, but imperially appointed intermediaries would face challenges understanding local conditions well enough to carry out their tasks, requiring a transition period to learn on the job.

What is commonly referred to as state centralization, thus, is shown to have involved Ottoman intermediaries and indirect rule.Footnote 37 Conversely, Ottoman historians, in many cases, interpret the proliferation of intermediaries (urban notables [ayan], partners of empire, participants, contractors) as “decentralized” rule, when “negotiation” and bargaining came to replace an idealized era of imagined direct “command” as the mode of rule.Footnote 38

But intermediaries were always part of the story of Ottoman rule. The real question is about what intermediaries actually did and achieved, about the outcomes of different modes of indirect control. Focusing on the actions and outcomes of intermediaries will hopefully enable analytical distinctions, for instance, between the kind of “decentralization” associated with Ottoman judges’ delegation of duties to deputies (naibs) and the kind of “decentralization” associated with the collapse of rural order and social structures.Footnote 39

At present, there does not seem to be any accepted method in the field of Ottoman studies to evaluate the role of intermediaries in imperial governance, and the continued use of “de/centralization” to describe Ottoman state capacity suggests a methodological impasse plaguing the field. There are two likely reasons for this impasse: the legacy of nationalist historiographies and the difficulty of evaluating intermediaries.

The “intermediary” concept has a history in the era of nationalist historiography, where, in many cases, “province” translated to nation-state. Albert Hourani’s study of urban notables (ayan), which emerged in the 1960s, had the unintended effect of overemphasizing local actors that resonated with the contemporary “maturing” of Arab nationalist narratives as well as prevailing structural-functionalist approaches and patronage system explanations within the academy.Footnote 40 The convergence of these trends and research agendas soon bred what one historian described as an “insurmountable opposition” between the [Halil] Inalcık-led “central” and Hourani-led “local” historiographies.Footnote 41

In the 1960s, almost immediate attempts were made to show that local intermediaries were integral to Ottoman governance and to harmonize the use of local and central sources; Hourani himself had tried to remedy this by emphasizing the Ottoman context of premodern Arab historiography.Footnote 42 These remedies did have effects as, in subsequent decades, the historiography shifted to framing the “center” and “local” as sharing a symbiotic relationship, not a zero-sum, antagonistic one. In the 1990s and 2000s, Ottoman historians continued to show that provincial elites and the Ottoman imperial bureaucracy (the center) negotiated with each other and worked together, with varying degrees of friction and contestation, to govern the empire.Footnote 43

However, the ballooning diversity of intermediaries and the inherent difficulty of evaluating what they did was the more serious difficulty that remained. To give an example, distinguishing between those who were originally dispatched from the capital to the provinces (Ottoman elites) and intermediaries recruited from the provinces (local elites) was one important way that historians taxonomized intermediaries. But the former could also transform into the latter. Ottoman elites “localized” and local, indigenous elites who participated in governance became “Ottomanized”; it was a “dual, interactive process of localization and Ottomanization” (italics in original).Footnote 44 This melting away of the central-local distinction over time made this particular taxonomy analytically fuzzy, especially when making diachronic comparisons.

In the initial setup of this taxonomy (i.e. before localization and Ottomanization), historians categorized Ottoman elites as the products of the devşirme “boy-tax” levy on Balkan and Anatolian Christians who received training in the capital before being dispatched to govern the provinces, even though they usually did not speak the local language. Over time, many such Ottoman elites became “localized” and intermarried with local women; some even established large households that persisted for generations.Footnote 45

In contrast, local elites were usually drawn from provincial notables and dynastic households. In some cases, they had a local powerbase, which Ottoman elites might not have had, as in the case of the Ma‘ans (local elites) and Sayfas (Ottoman elites) in Mount Lebanon.Footnote 46 These local elites became “Ottomanized” by learning Ottoman Turkish and culture, competing for government posts, and then serving as government officials; this process could vary widely across the empire.Footnote 47 In some contexts (such as the Balkans in the period leading up to and including the Russo-Ottoman war of 1768–74), local notables paid to obtain official statuses and titles.Footnote 48

Ottoman intermediaries could also be categorized according to their origins, not only how they were appointed to their position within the bureaucratic hierarchy. Historians have discerned, for instance, “east-west” antagonism along ethno-religious lines between “westerners” (from the Balkans and western Anatolia) and “easterners” (from the Caucasus and Georgia). Historians have shown how this antagonism structured the dynamics between local intermediaries and the imperial bureaucracy (the state), as well as attempts to redraw the boundaries outlining who could belong within the state elite.Footnote 49

Historians have also created more granular taxonomies within the category of local elites by, for instance, distinguishing between the “localizing governing elite and emerging notable elite” and breaking down the category of “notable” into sub-categories comprising the local religious establishment, janissary garrison chiefs, “secular” notables, and Bedouins who facilitated and provided security for the pilgrimage.Footnote 50 This ballooning range of provincial intermediaries and their relationship with the imperial bureaucracy becomes more confusing to analyze when, over time, some of these groups emerged, faded away, or merged with others. Layered upon this confusion are the different terms used by different historians, and also the same terms used to refer to different kinds of intermediaries.Footnote 51

To summarize the foregoing points, the proliferation of intermediaries constitutes the core problématique underlying our understanding of Ottoman state formation. The success of the Ottoman state in recruiting Ottoman subjects into its imperial project were such that even residents of the relatively remote desert oases in upper Egypt were known during the 17th and 18th centuries to have joined the military and achieved social mobility within the Ottoman system.Footnote 52 But by the same token, the organizational hierarchy and structural relations that intermediaries shared with each other in local contexts become more difficult to analyze from a macro imperial perspective. Perhaps, for all these reasons, even the most important historical sociological study of the Ottoman Empire simply assumed away the structural relation between different intermediary groups, assuming a hub-and-spoke model in which the spokes did not interact with each other.Footnote 53

There are important exceptions in the historiography that provide instructive guidance for future research. Some scholarship has been able to elucidate the administrative relationships that different local intermediaries had with each other. For instance, a recent study showed how the Ottoman state managed to achieve “upwardly accountability” by delegating power to the provincial governor (of Diyarbekir province), who could intervene in the judge’s court of the city of Harput, a sub-district of the same province. This shows the structural relation between two kinds of intermediaries and its impact on Ottoman governance. However, this accountability was achieved at a cost, as this process of empowering local officials contributed to tensions and possibly to the eventual separation of these regions from the empire.Footnote 54

Sometimes, the cultivation of groups of intermediaries changed local social and cultural dynamics. In the case of 18th-century Ottoman Syria, local ‘Alawis’ increased participation in imperial governance reinforced ‘Alawi identity and sense of community; rather than being a community forged in opposition to imperial power, the ‘Alawis were made by it. This consolidated communal identity had the later consequence of conferring upon the ‘Alawis the reputation of comprising a “uniform sectarian faction (taife/ta’ifa) pursuing a single political goal,” which local Ottoman officials would eventually perceive as a threat.Footnote 55 The embedding of intermediary communities in imperial governance processes might pose, consequently, threats or counterweights to other Ottoman officials (other kinds of intermediaries).Footnote 56

Again, I wish to contrast the empowerment of local intermediaries with the actual collapse of order. The two phenomena can certainly be connected, but this has to be shown. In the 18th century, for instance, in the conflicts between Ottoman military personnel stationed at frontiers and local representatives of life-term tax farmers residing in Istanbul, the state often allowed the latter’s fiscal interests to prevail. Life-term tax farm revenues were thus prioritized over military funding, contributing to the erosion of imperial control over these frontier troops.Footnote 57 Another example, this time from 18th-century Mughal Ahmedabad, shows how the proliferation of local intermediaries could result in a confused chain of command and unclear scope of jurisdiction that ultimately led to the breakdown of local order.Footnote 58 Indeed, historians have long noted the proliferation of intermediaries in different imperial contexts, using various terms to name this phenomenon (such as a “chain of deputies,” “thickening governance,” and even “proto-democratization”). The next step, I suggest, is to show concretely how increased intermediaries affected imperial operations in each context.Footnote 59

The brief sketch above shows that proliferating intermediaries can be arranged in organizational structures that look different from each other, and that task delegation can produce different outcomes. This variation in structure, process, and outcomes underscores the particularity of each empire’s historical trajectory; there must be respect even for a narrative of collapse, and that respect manifests in excavating the specific, idiosyncratic detail of that empire’s unraveling. To reiterate, the argument in this section is that historians cannot assume weakened imperial control on the sole basis of a proliferation of intermediaries.Footnote 60

Two Pathways

How can we make sense of the proliferation of intermediaries in early modern states? In the final section of this review essay, I discuss two possible paths out of this methodological impasse. The first method focuses on one type of intermediary, the tax collector, while the second method offers a way of organizing a variety of intermediaries, which may in turn enable more precise definitions of the concept of the intermediary.

Quantitative Economic History: Calculating Ottoman Fiscal Capacity

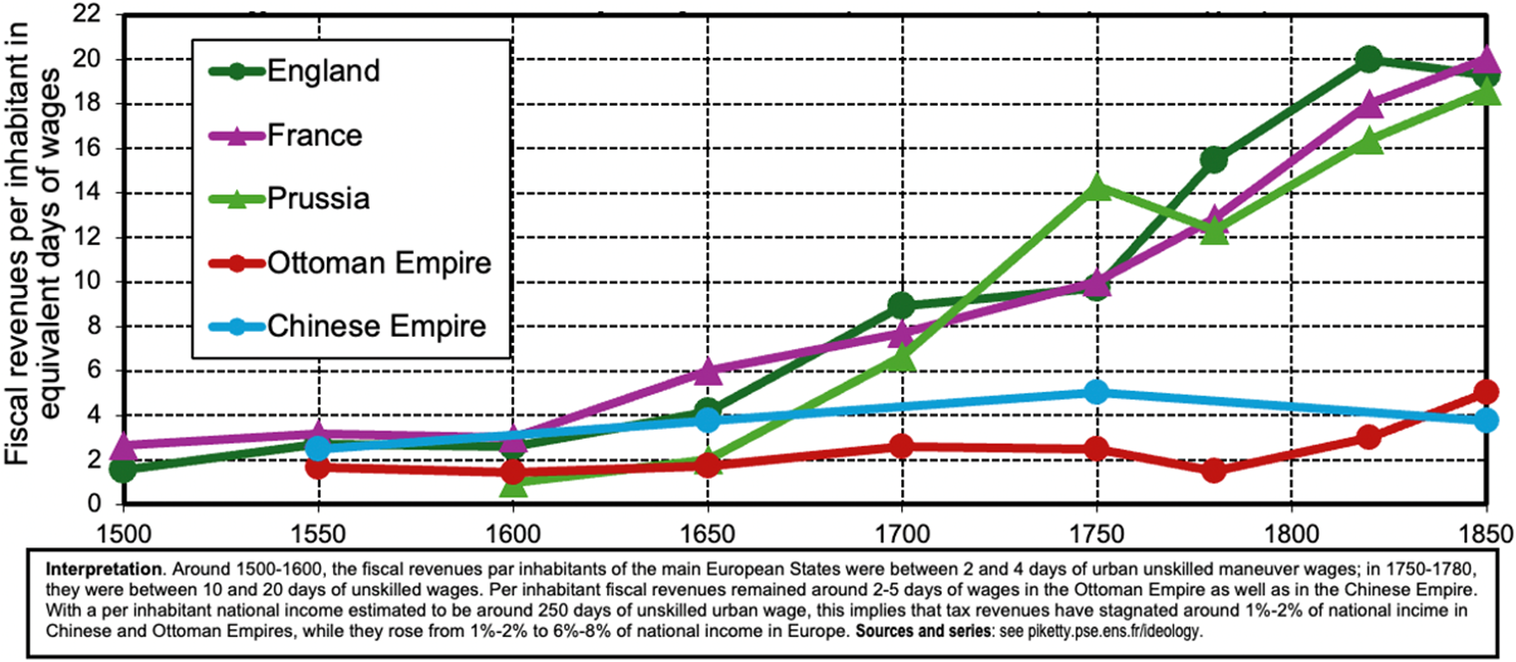

Fiscal capacity, an important dimension of state capacity, is commonly defined as the central state’s ability to extract tax receipts per inhabitant in its territories relative to total national income. This quantitative metric is what allows macro-historical comparisons between the Ottoman Empire, the “Chinese empire,” and European states such as England, France, and Prussia across centuries, as demonstrated in Figure 1 below, taken from economist Thomas Piketty’s recent study.Footnote 61 In this context, the more centralized a state, the more tax receipts it can extract per inhabitant relative to total national income (there can be similar moves made for legal capacity and military capacity; the debates there surround what to quantify and how).

Figure 1. The fiscal capacity of states, 1500–1850 (days of wages)

Source: Piketty, Capital and Ideology, 366, http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/fr/ideology.

Many, if not most, Ottoman historians are qualitative historians and would reject the premise of quantitative historical work, or even the need to compare with early modern European states. If this is the kind of forest one must have, then many might be happy just to focus on trees. Yet much qualitative Ottoman historical research has been influenced by these same social science approaches and European historiographies – the frameworks and vocabulary we use are language derived from those fields of study. To give an obvious example, the centralization-decentralization-centralization periodization repeated over the past three decades by Ottoman historians was itself influenced by Charles Tilly’s important social scientific work on early modern European states.Footnote 62 However, Europeanists have long revised Tilly’s core assumptions regarding early modern European state centralization, showing that Tilly vastly overestimated such states’ capacities and the fact that they relied tremendously on a range of intermediaries and contractors.Footnote 63 Ottomanists should thus move on from this outdated language.

In fact, the (qualitative) Ottoman scholarship briefly surveyed above in the previous section can be brought to bear on future (quantitative) studies of the Ottoman state’s fiscal capacity: specifically, on how Ottoman fiscal capacity is calculated. Whereas a previous, pioneering quantitative study on fiscal capacity only counted centrally received tax revenues, future studies could also include provincial tax receipts, in-kind services and obligations.Footnote 64 After all, what happened in the provinces matter for assessing fiscal and state capacity, because pre-industrial states “often mandated that provincial governments carry out particular activities and raise the money to do so.” Fiscal capacity should therefore consider resources collected at local and provincial levels, including non-monetary resources such as corvée, conscription, and in-kind taxes; neglecting them “underestimates state resources more in some societies than others,” particularly in societies with lower levels of monetization.Footnote 65 Using central treasury revenues as an indicator of military capacity as some economic historians do is therefore also flawed, because the bulk of the resources that supported the Ottoman military were based on provincial land grants.Footnote 66

Crucially, provincially collected tax receipts should not always be seen as revenues captured by provincial groups at the expense of the central government. If the Diyarbekir governor recorded a much greater annual revenue in 1670–71 compared to his predecessor in the 16th century after adjusting for inflation, then this can be explained in a variety of ways (greater tax collection capacity; greater agricultural productivity), not only by the fact that provincial groups benefitted and the central treasury lost out.Footnote 67 It was a widely accepted fact that provincial revenues were not all transmitted to the imperial capital.Footnote 68

The point here is not to claim that the Ottoman state was radically stronger and more successful relative to contemporary European states. Even if all provincial tax receipts (cash and in kind) were calculated, the results are unlikely to reveal a dramatically different picture of Ottoman state capacity. However, the relative differences within the empire among Ottoman provinces can be instructive for qualitative work. If social scientists are going to develop quantitative claims anyway, why not modify their accounting methods of state capacity in light of these new insights?

Social Science: The Competence-control Tradeoff

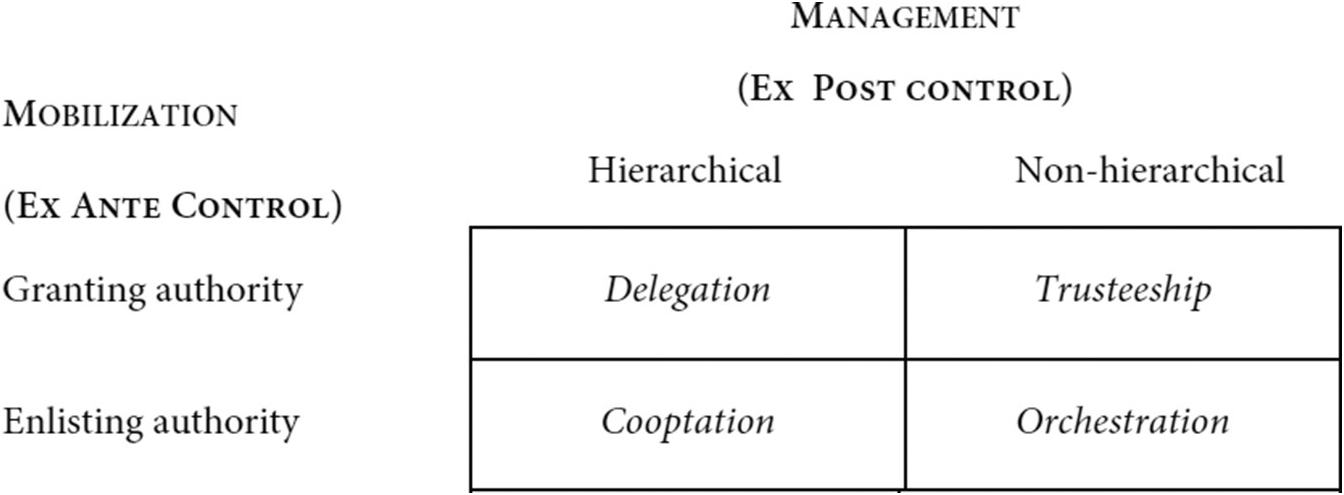

If the quantitative method privileges tax collectors as the only intermediary of relevance, social scientists of a more sociological bent have developed an approach that considers different kinds of intermediaries. Social scientists studying the Merovingians and Carolingians, for instance, have developed a schema to explain the competence-control tradeoffs governors face when managing and mobilizing intermediaries (or agents). The idea is that a governor is faced with a dilemma: he can either have a highly competent intermediary or strong control over his intermediary, but not both.Footnote 69

In this schema (shown in Table 1), a governor can manage an intermediary in two general ways: hierarchically (with the authority to remove an intermediary) or non-hierarchically (without the authority to remove an intermediary, needs to rely on soft power or other means). Similarly, a governor can mobilize an intermediary to fulfill his goals in two ways: by granting authority (delegating authority to empower an intermediary) or enlisting authority (persuading an intermediary to use his/her existing authority to do certain tasks).

Table 1. Four modes of indirect governance

Source: Kenneth W. Abbott, Philipp Genschel, Duncan Snidal, and Bernhard Zangl, eds., The Governor’s Dilemma: Indirect Governance Beyond Principals and Agents (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

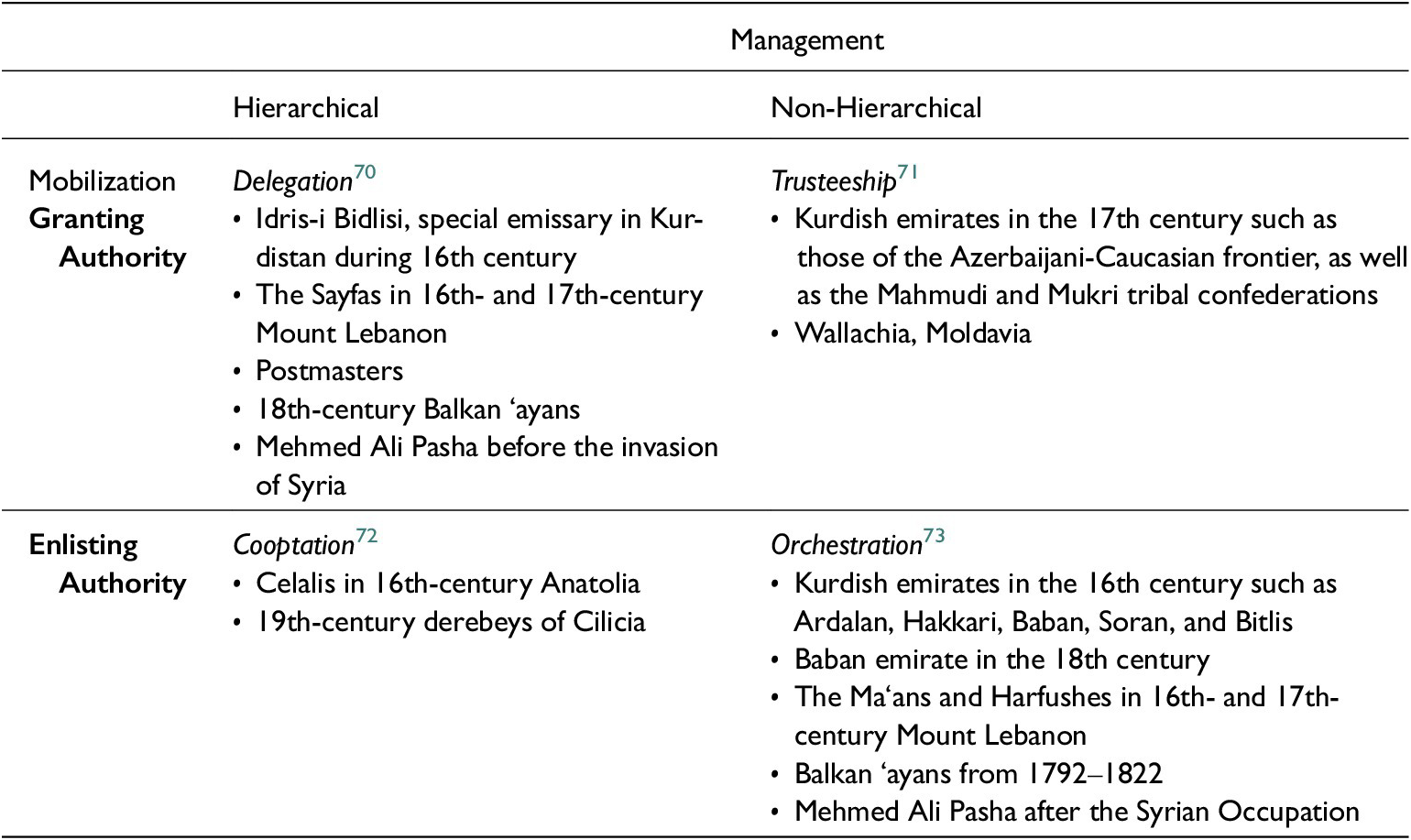

When translating this schema to the Ottoman context, I have substituted the Ottoman state (imperial bureaucracy) for the position of the “governor.” In Table 2 below, I have adapted this schema and filled in the intermediaries in the 2 x 2 table. An advantage of this schema is that the same broad category – such as the Kurdish emirates – can be disaggregated into more specific examples, down to geographical location and time period.

Table 2. One way of organizing Ottoman intermediaries (based on Kenneth W. Abbott, Philipp Genschel, Duncan Snidal, and Bernhard Zangl, eds., The Governor’s Dilemma: Indirect Governance Beyond Principals and Agents (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020)

Idris-i Bidlisi, the special emissary in Kurdistan from 1514–1516, who helped Selim I (r. 1512–20) broker military alliances there, is an example of an intermediary the Ottoman state had hierarchical authority over (it could dismiss him easily) and to whom authority was delegated. This hierarchical management relation and mobilization style made sense for the job scope that Bidlisi was charged with accomplishing.

Indeed, the Ottoman state had to rely on soft power (and on intermediaries such as Idris-i Bidlisi) to keep various Kurdish emirates within the empire whether in the 16th, 17th, or 18th centuries. This non-hierarchical form of management was due to the fact that the Ottoman state lacked the capacity to completely remove these emirates. Depending on the time period and specific emirate, however, the mobilization style differed: the Ottoman state either granted authority (trusteeship) or enlisted authority (coopted intermediaries through persuasion, incentives or some other means to do certain tasks). This was a qualitative judgment call.

For many, this 2 x 2 schema will not be sufficient. It is but a first step in finding patterns among multiple instances of these fine-grained qualitative studies on intermediaries, if that is a research desideratum for some.

These two suggested approaches each have their pros and cons. Focusing on just one type of intermediary – the tax collector – enables historians to answer the question of what governance outcomes were; conveniently, in this case, the outcome is a number representing the state’s fiscal capacity. But this first method has the drawback of ignoring other types of intermediaries and, therefore, the range of governance activities the state was able to undertake through them. The second method has the virtue of offering a taxonomy of a range of intermediaries, but it is less able to concisely answer the question of governance outcomes. It also has the virtue of allowing multiple intermediaries operating within the same administrative unit (such as a province or district or sub-district) to be listed concurrently in the same table, which may facilitate analysis of their relations with each other (in Barkey’s language, this 2 x 2 schema renders relations between layers of spokes perceptible, and just relations between the hub and spokes.)

Moving Forward

I suggest that the time has come for historians to move beyond the centralization-decentralization-centralization paradigm. As I understand it, the persistence of this paradigm is a symptom of a methodological impasse plaguing the field, and I propose that the reason for this impasse is the difficulty of perceiving the continuing process of Ottoman state formation in an age of proliferating intermediaries. In providing this diagnosis, this review essay has built upon important historiographical interventions that characterize the empire’s center-periphery dynamic as “Ottomanization,” “localization,” “centripetal decentralization,” and the “politics of difference.”Footnote 74 I locate the analytical path out of this quandary in the taxonomy of these numerous intermediaries.

In this vein, I have proposed two approaches: a quantitative approach that privileges tax collecting intermediaries and a schema that categorizes intermediaries according to how they were managed and mobilized. Both approaches make assumptions and have limitations, just as qualitative historians who continue to use the concepts of centralization and decentralization also make assumptions that have limitations. The goal should not be to avoid assumptions entirely; as a field of study, however, it may be desirable for us to experiment with frameworks that use different assumptions in order to avoid collective blind spots. What is at stake here is an accurate appreciation of the true scope of Ottoman government activity after the 16th century.

For many qualitative historians, what is at stake is perhaps something more mundane: a simple, shorthand way to set the scene for their main subject of research. De/centralization is not something they fervently believe in, but it undeniably provides a useful, macro throughline of centuries of history that could be used to create a wide lens, establishing shot for their narrative. After all, what alternatives exist?

The scholarly literature already offers many possibilities beyond de/centralization. Historians have observed several important trends during the 17th and 18th centuries. On the one hand, Ottoman society opened up socially, culturally, and architecturally (historian Shirine Hamadeh calls this décloisonnement). New fashions, vegetables, and fruits from the New World were imported into the Ottoman Empire; Ottoman builders selectively incorporated European architectural styles in sultanic mosques of this period; barbers and non-elite individuals engaged in literary production that was previously an exclusive preserve of the elites; and urban spaces hosted a new kind of sociability marked by the consumption of coffee and tobacco in public.Footnote 75

On the other hand, there was a parallel pattern of group formation called corporatism or communalization by historians.Footnote 76 Corporate groups emerged across the social hierarchy, whether these were professional associations such as guilds, associations along lines of identity (such as the blind), villages and neighborhoods,Footnote 77 self-conscious confessional groups and sufi orders,Footnote 78 or powerful provincial households.Footnote 79 Many of these groups participated in Ottoman governance which, in some aforementioned cases, recursively reinforced their corporate identities and boundaries.

These are some macro patterns of the 17th and 18th centuries that have long been observed by historians, and they can serve as suitable substitutes to the de/centralization paradigm. It is feasible, and possible, to move beyond this impasse.

Acknowledgements

I have workshopped the arguments here in over a dozen settings for almost four years and have had long and deep conversations (contestations!) with several colleagues on this topic. For their helpful comments, time, and energy, I would like to thank Yiğit Akın, Virginia Aksan, Metin Atmaca, Marc Aymes, Sohaib Baig, Jean-Philippe Bombay, Hulya Canbakal, Metin Coşgel, Kevan Harris, Jane Hathaway, Erdem Ilter, Colin Imber, Kıvanç Karaman, Nihal Kayalı, Victor Lieberman, Tamara Maatouk, Azeem Malik, Bruce Masters, Can Nacar, Michael Provence, Francesca Trivellato, Masayuki Ueno, Nicolas Vatin, Luke Yarbrough, Meng Zhang, and the engaging audiences at the Luke Yarbrough’s After Antiquity workshop at UCLA, the Social Science History Association conference 2024 (Andrew Chalfoun, Sam Dunham, and Ben Kaplan), and Virginia Aksan’s “Putting the Ottomans on the Map” conference at McMaster University in 2024 (Palmira Brummett, Boğaç Ergene, Elisabeth Fraser, Myron Groover, Gottfried Hagen, Dina Rizk Khoury, Harun Küçük, Ethan Menchinger, Veysel Şimşek, Ahmet Tunç Şen, Will Smiley, and Adrien Zakar). I thank Amina Elbendary and History Compass, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback on an early draft, and for allowing me to withdraw this article when it grew too long for their journal. I thank Joel Gordon for gamely taking this submission on and for his astute comments that improved the piece. The views and mistakes here are solely my own.