A. Introduction: Reluctant Judges or Inactive Parties?

The preliminary reference procedure is the most important instrument of judicial integration in the EU. Thanks to this form of “judicial dialogue,” national courts can send questions regarding the interpretation or validity of EU law to the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU).Footnote 1 This procedure not only enables national courts to ask for an authoritative interpretation from the CJEU, but it also makes them crucial actors in the decentralized enforcement of EU law.Footnote 2 But what if national courts do not engage in this judicial dialogue and remain silent?

Most research on the lack of preliminary references has focused on national judges, exploring the political, institutional, and pragmatic motives behind their choice to withhold references.Footnote 3 This article, rather than focusing exclusively on judges, uses the legal mobilization framework to widen the lens of the inquiry and to include litigants and lawyers.Footnote 4 Legal mobilization refers to the use of law by individuals or groups, to influence policy, culture, or behavior.Footnote 5 As such, it is broader than strategic litigation but closely related to it. Applying a legal mobilization approach means treating courts as reactive actors, asking whether litigants and lawyers have tried to persuade judges to refer, and, if so, why they have failed. Notably, when legal mobilization is absent, strategic litigation is absent too.

By investigating the lack of references, the article contributes to fill a blind spot in the studies of legal mobilization and strategic litigation. Indeed, cases where rights remain unclaimed have been seldom addressed by scholars. As Börzel rightly observed, scholars tend to focus on cases where rights are mobilized against governments, leaving understudied cases where people do not go to court.Footnote 6 But arguably these are the best suited to detect the obstacles that individuals, lawyers, and civil society actors may encounter on their road to justice.

This paper takes Greece as a case study to investigate the absence of EU litigation on third-country national migrants. In recent years, we have seen a rise in preliminary references and strategic litigation around migration and asylum law.Footnote 7 However, these references predominantly come from the same few countries, while many Member States have mobilized the rights of migrants before the CJEU only seldomly.Footnote 8 It is thus important to understand the reasons behind this lack of references and which factors hamper litigation before the CJEU. In this context, Greece is particularly puzzling given that it has been affected by extreme migration flows since 2008, and many legal NGOs operate there to support migrant rights.

The article leverages the findings from cases where EU litigation was present to assess if they can assist us in elucidating a case where EU legal mobilization is missing. More specifically, relying on existing research, the article identifies the structural and subjective factors that have facilitated the activation of the preliminary reference procedure elsewhere. Then, it tests whether the lack of one or more of these factors can explain the absence of references in Greece.

By combining judicial politics and legal mobilization theories, the paper offers new insights into the conditions for the activation of the preliminary reference procedure. The article shows that, in the examined case study, the absence of references was due to a combination of structural and subjective factors, confirming the importance of studying both. On the one hand, national procedures presented important constraints to access to the Court of Justice, as they make it difficult for migrants to reach the Greek highest courts. On the other hand, Greek migrant defenders had not fully incorporated preliminary references in their strategies yet; actors have a pessimistic view of the judiciary’s propensity to refer, lack familiarity with the preliminary reference procedure, or prefer alternative venues such as the European Court of Human Rights. This study calls for the need to better understand the process that leads to the formation of EU legal consciousness, pointing at the important role that legal experts and academics can play. Even if legal opportunities for mobilization exist, they will remain dormant until they are perceived as such and strategized by actors.

The article is structured as follows. The next section formulates two hypotheses to explain the lack of references by drawing on the main theories in the field of legal mobilization and judicial politics. Section C explains the case selection, providing data on migration references in Greece and the other Member States. Section D tests the first hypothesis, which deals with domestic courts and structural factors. Section E instead investigates the role of the actors of strategic litigation: organizations and lawyers for migrant rights. Finally, section F outlines the main findings.

B. Factors Explaining (the Lack of) Legal Mobilization Before the CJEU

The literature offers two main sets of theories to explain the (non-)emergence of legal mobilization. The first concerns structural factors, also known as legal opportunity structure. The second concerns the actors that mobilize the law, or who are supposed to do so. The next subsections build on these theories to derive two hypotheses.

I. Structural Factors: The EU Legal Opportunity Structure

The “legal opportunity structure” (LOS) concept derives from the analogous “political opportunity structure,” which was developed by social movement scholars.Footnote 9 The central idea is that the political environment, by providing incentives or disincentives to act, shapes social movements’ expectations regarding the success of collective actions, and consequently affects actors’ decision to mobilize.Footnote 10 We still lack an agreed-upon definition of LOS and, as Vanhala critically noted, scholars tend to use it to indicate “[v]irtually anything that can be seen as having helped a movement mobilize or attain its goals.”Footnote 11 Because defining LOS in over-comprehensive terms risks undermining its analytical value, I decided to consider part of the LOS only the factors external to the mobilizing actors. These pertain to three main categories: The available law, judicial receptivity, and the rules on access to courts.Footnote 12

Despite calling these factors external, I do not imply that mobilizing actors suffer them passively. On the contrary, as suggested by Vanhala, actors can impact structural factors and shape them.Footnote 13 Additionally, in conceptualizing the LOS, it is important to bear in mind that opportunities for legal mobilization exist only to the extent that movements perceive them as such. As Tarrow argued regarding political opportunities: “[T]here is no such thing as ‘objective’ opportunities – they must be perceived and attributed to become the source of mobilization.”Footnote 14

The subjective nature of mobilization opportunities means that rights and remedies need to be perceived, understood, and mastered to be mobilized. In the legal field, this insight resonates with the concept of legal consciousness. This refers to the idea that people see and understand the law in different ways depending on their biography, experience, and personal situation; these sociological and biographical elements shape people’s encounters with law, courts, and authorities.Footnote 15 Individual perceptions are important not only because they shape how people understand the available rights—the legal stock—but also because they determine whether actors recognize and seize opportunities for mobilization. For instance, a recent study in the migration field showed that two different pro-migrant organizations, even if acting in the same legal and procedural context, enacted different legal strategies because of their divergent views about the LOS, and specifically about judges’ propensity to refer.Footnote 16 Thus a judicial system that seems closed and impenetrable to some, might appear accessible and full of opportunities to others.

These legal mobilization theories need to be adapted to the specific migration and preliminary reference mechanism context. Indeed, the interaction between the national and the EU opportunity structure is complex, and the outcome is not always in the direction of empowering individuals.Footnote 17 The preliminary reference procedure, despite being used to enforce EU rights, remains “a procedure from court to court” that sits between the national and the supranational level.Footnote 18 Litigants first need to gain access to national courts to then have their cases referred to the ECJ; this means that the national structure of opportunities, with its rules on access to court, heavily determines the EU LOS. Moreover, EU law is part of a multilevel system of rights and remedies where it represents only one legal strategy among many.Footnote 19 The same claim may often be framed by using national, EU, or international law; and the choice of legal source determines the suitable remedy and court—national and constitutional court, CJEU, etcetera.

For these reasons, when identifying the factors that can explain the presence or absence of legal mobilization before the CJEU, it is crucial to look at the interplay between the national and the EU legal systems.Footnote 20 Alter and Vargas have found that litigants must identify a specific aspect of EU law from which they can draw upon to advance their political claim.Footnote 21 This was confirmed by further studies that specified that litigants must perceive EU law as more advantageous compared to other national remedies.Footnote 22 Moreover, access to the CJEU crucially depends on national judges’ receptivity, who must be willing and able to refer. Such specific judicial receptivity might depend on many different factors—for example, competition-between-courts dynamic,Footnote 23 the judicial review culture,Footnote 24 or attitudes towards the EU.Footnote 25 I have also observed that judicial receptivity is not immune to the influence of mobilizing actors. Through judicial training, conferences, and academic articles, migrant rights defenders can make a judge more prone to refer.

All this considered, the first hypothesis for the lack of references is that Greece’s structure of opportunities for EU legal mobilization is closed. This may be due to:

-

a) Legal stock: EU law does not offer a comparative advantage with respect to Greek law;

-

b) Judicial receptivity: Greek judges are unwilling or unable to refer;

-

c) There is no access to courts.

II. Subjective Factors: Actors, Resources, and Legal Consciousness

Structural factors are only part of the explanation. An open LOS is not sufficient per se to explain the emergence of EU legal mobilization, as EU legal opportunities can be seized only by the actors that possess the necessary resources, such as funding and legal skills.Footnote 26 While the LOS refers to factors that are external to the mobilizing actors, mobilization resources refers to internal factors,Footnote 27 which, it is argued, are equally important to explain the lack of EU litigation.

The most important resource for legal mobilization is the presence of a support structure.Footnote 28 In the case of migrant rights, this often consists of altruistic actors, that is, actors who are not migrants but mobilize on their behalf.Footnote 29 This is especially true for migrants who are newcomers to Europe and who do not have a clear understanding of the law, their rights, and even less of EU rights and procedures.Footnote 30 For this reason, their mobilization crucially depends on the help provided by altruistic actors who supply fundamental information and know-how for the litigation.

In the specific preliminary reference context, mobilizing actors need to persuade a national judge to refer. To this end, it is important to show excellent knowledge of EU law, which is a critical resource often provided by allies. These can be Eurolawyers: “[P]art insiders of the EU legal field, part members of their local community” who can facilitate the mobilization by harnessing local contenders.Footnote 31 Another frequent ally of migrant rights defenders is EU law academics: Thanks to their expertise, they can identify whether an EU norm can be used to challenge a state action; they indicate it to the movements, which act accordingly.Footnote 32 By shaping the perceptions and legal consciousness of mobilizing actors and national judges, academics and legal experts can hugely influence the decision to mobilize and the success of the legal mobilization.Footnote 33

In the litigation context, another key resource amounts to the money to pay for the financial cost of the proceedings. Compared to other mobilization strategies, such as political campaigning, legal mobilization is quite cheap, but still, we should not ignore this financial aspect that can be important in the underfinanced world of pro-migrant activism.

Building on these considerations, I have formulated a second hypothesis to explain the lack of mobilization. According to this, the lack of EU legal mobilization can be explained by a lack of resources, which translates into:

-

a) Altruistic actors: There is a lack of migrant rights defenders.

-

b) Material and intellectual resources: There are migrant rights defenders in Greece, but they lack funding, Euro-expertise, or expert allies.

Sections D and E will use empirical evidence to test the hypotheses illustrated above. But first, the next section explains why Greece is a suitable case study.

C. Greece and its Puzzling Lack of References

I identified Greece as a case study for two main reasons. First, after looking at my database containing all the preliminary references in the migration and asylum fields up to December 2022—a total of 505—Greece stands out as being one of the few EU countries that has never referred a preliminary question.Footnote 34 Second, the Greek socio-political context seems a fertile terrain for EU legal mobilization for migrant rights, thus making its absence particularly puzzling.

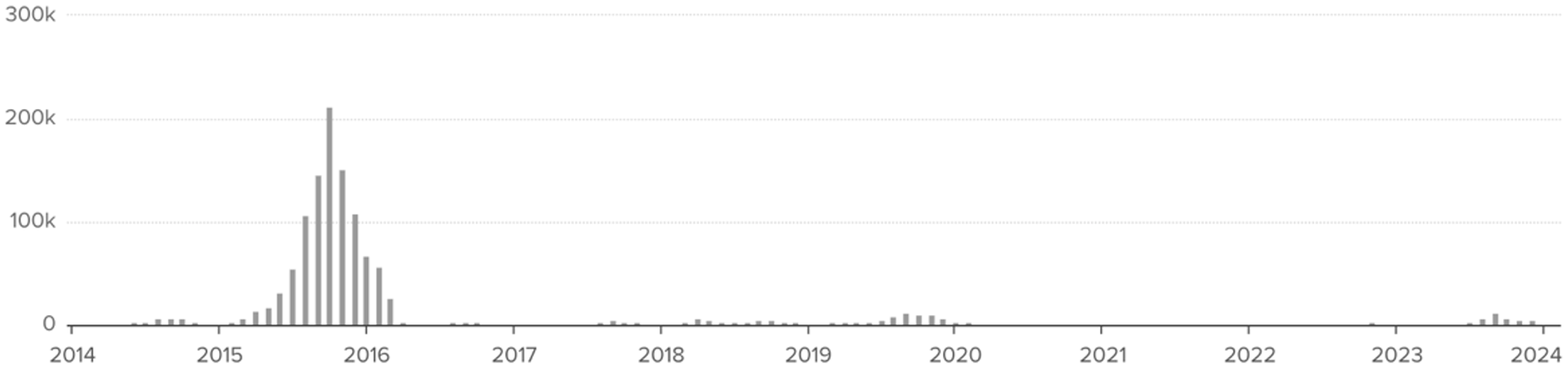

As of December 2022, four EU countries never submitted a preliminary reference in the migration field: Greece, Malta, Portugal, and Slovakia—displayed in Figure 1. To be suitable case studies, the Member States must have structural characteristics that do not automatically exclude the possibility of having references in the migration field. For instance, a country like Slovakia, with a relatively small migrant population, would not qualify.Footnote 36 Another important factor is that, in general, new Member States have a lower number of references compared to old ones.Footnote 37 This is particularly relevant for our sample because almost all the countries with low reference rates, including Slovakia and Malta, joined the Union in or after 2004. Their status as new Member States likely explains the lack of references.

Figure 1. Preliminary references in the migration field per referring country from 1981 until December 2022. Source: author’s original database based on Curia and NEMIS, NEAIS, and NEFIS newsletters.Footnote 35

After excluding these countries, we are left with Portugal and Greece, and the latter is arguably the most puzzling one because, on paper, it would be the most likely to feature EU legal mobilization in the migration field. Greece joined the EU in 1981 and since 2010 the country has faced “extreme migratory pressure.”Footnote 38 In that year, “the Greek external land and sea border accounted for 90% of all detection of irregular border crossing along all EU external land and sea borders.”Footnote 39 Since then, Greece’s pivotal importance in European migration policy has only grown, until reaching its peak in 2015 and 2016 with the so-called refugee crisis.Footnote 40 Greece’s already deficient asylum system proved unprepared to receive big influxes of people and the rights of migrants and asylum seekers were systematically violated. The ECtHR has certified these violations by condemning Greece several times,Footnote 41 which makes the absence of references to the CJEU even more puzzling.

Our puzzle deepens if we consider that Greece features an important presence of altruistic actors working in the migration and asylum field, that provide a “support structure” for legal mobilization.Footnote 42 Among the local and international NGOs that help migrants, many specialize in the provision of legal assistance throughout the asylum procedure. This suggests that Hypothesis 2(a) of this paper—lack of migrant rights defenders—does not hold for the Greek case.

A final aspect that points to Greece as a likely case for EU legal mobilization arose when the research for this study was already in course. In 2023, two Greek courts submitted a reference in the asylum field for the first time: the Greek Council of State in February,Footnote 43 and the Administrative Court of Thessaloniki in August.Footnote 44 While these cases fall outside the scope of my investigation, which covers the period up to December 2022, they nevertheless suggest that Greek courts can make migration references, leaving unanswered the question of why they haven’t done so before.

The next sections will test the two hypotheses described in Section B. To do so, I have analyzed the Greek judicial framework by gathering data on national and international judicial activity. I have complemented this with ten interviews, one with a Greek judge and nine with migrant rights defenders, and several informal conversations with Greek academics and practitioners.

This study has two important limitations. The first regards access: except for apex courts, Greek courts’ judgments are not publicly available. The second regards interviewing as a method: Lawyers and judges may understandably be reluctant to admit their responsibility for the lack of preliminary references, which is why I tried to triangulate interviews with other types of data.Footnote 45

D. Structural Obstacles: The EU Legal Opportunity Structure in Greece

This section examines whether structural factors can explain Greece’s lack of migration references. As explained in the introduction of the special issue, structural factors relate to the features of the legal order where litigation takes place. In legal mobilization language, this translates into assessing whether Greece has a closed legal opportunity structure (LOS). As said in section B, for the LOS to be open we need to meet three conditions: 1) EU law should present significant advantages compared to Greek law, i.e. being more protective of migrant rights; 2) domestic judges shall not be structurally reluctant to refer; 3) actors must have access to national courts. The following subsections will verify each of these conditions in the same order.

I. The Comparative Advantage of EU Law

During the last thirteen years, academics and NGOs have documented severe flaws in Greece’s asylum and migration systems, considered below European standards.Footnote 46 Since 2009, Greece has been “under the spotlight because of its continuing inability to provide effective protection to asylum-seekers arriving at its shores,” as provided by EU law.Footnote 47 The inconsistencies with EU law have been ascertained by the EU Commission too, which opened an infringement procedure in 2010.Footnote 48 Several judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) found the detention and living conditions in Greece degrading,Footnote 49 and the CJEU found its asylum reception system to have “systemic deficiencies” in one of the most famous strategic litigation cases ever brought, N.S. and Others of December 2011.Footnote 50 Notably, this case was referred by Irish and British courts, and not by Greek courts.

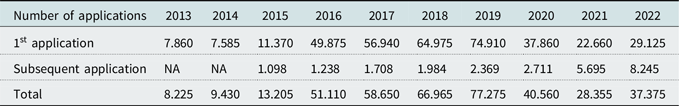

In 2014, Greece’s already deficient asylum system had to face one of the biggest people’s exodus in European history, the so-called “refugee crisis” triggered by the Syrian war. From 2014 to 2016, more than a million asylum seekers arrived in Greece to take the Balkan route and reach northern European countries, as displayed in Figure 2. This massive transit came to a halt in March 2016, when the EU Member States and Turkey signed the controversial EU-Turkey Statement, under which Turkey agreed to take back all Syrian nationals who arrived in Greece via Turkey.Footnote 51 Interestingly, the subsequent decrease in arrivals did not lead to better reception conditions.Footnote 52 This is somehow reflected in more recent preliminary references from Germany which report that refugees cannot be sent back to Greece because they would run “a serious risk of being subjected to inhuman or degrading treatment.”Footnote 53

Figure 2. UNHCR data on monthly sea and land arrivals to Greece, 2014-2024.Footnote 54

Already from this brief analysis, we can say that invoking the respect of EU law would have presented considerable advantages for migrant rights. According to NGO reports, Greece fails to fulfill its EU-derived obligations in three main areas: Access and quality of the asylum procedure, treatment of vulnerable individuals, and detention of undocumented migrants. Coherently with the idea that the preliminary reference procedure is the “infringement procedure” of the European citizen, these are also the areas where we should expect the emergence of EU legal mobilization.Footnote 55 Indeed, EU law could have been invoked before the CJEU to challenge Greece’s practice and ask the CJEU to ascertain the incompatibility with EU standards. But this has not happened.

II. Greek Judges’ Real or Supposed Reluctancy to Make Preliminary References

When asked why there are no migration references from Greece to the Court of Justice, the common answer is that Greek judges are reluctant to refer: “The low number of preliminary referrals by Greek courts could indicate a general reluctance to make use of the CJEU machinery.”Footnote 56

This conviction was corroborated by an important decision. As mentioned, in 2016 the Member States concluded the EU-Turkey Statement, whereby the Turkish government committed to readmit Syrian nationals who arrived in Greece. Two cause lawyers tried to challenge the Statement by supporting the appeal of two Syrian nationals who risked being readmitted to Turkey. The case progressed to the last instance administrative court, the Greek Council of State, where the lawyers asked to submit a preliminary reference regarding the definition of Turkey as a safe third country.Footnote 57 The Council ruled with a slim majority of 13/12 that there is no reasonable doubt on the meaning of safe third country under EU law, thus there is no need to request a reference.Footnote 58 Among the many dissenting judges, two were vice presidents, a testament to the fracture within the Council of State—and arguably to the fact that there were some doubts regarding the interpretation of the norm. The Council of State’s decision not to refer has led to speculation that the judges may be influenced by politico-strategic factors and are reluctant to refer sensitive questions to the CJEU.Footnote 59

However, in the past, the Greek Council of State did not avoid references in delicate cases of potential constitutional clashes and instead, it engaged in constructive dialogue with the CJEU.Footnote 60 Moreover, when discussing the political motives behind judgments, it is difficult to discern reality from speculation: even if individually interviewed, a judge would hardly admit that their decisions are politico-strategic and thus not neutral.Footnote 61 And even admitting that the Council of State’s decision not to refer was politically motivated, it seems far-fetched to think that, for a decade, all Greek judges, from any court and tribunal, systematically refused to refer for politico-strategic reasons.

While obtaining evidence regarding the political motivations behind references can be challenging, we do possess data that allows us to assess whether Greek judges are reluctant to refer. Data on Greece’s referral rate shows that Greece is among the Member States that refer the least, placing itself in the 20th position. However, with its 10 million inhabitants, Greece is also one of the smallest States and if we check by population size, the result changes quite dramatically.Footnote 62 Perhaps even more noteworthy, the Greek last-instance administrative court, the Council of State, which is in charge of migration and asylum cases, exhibits a significantly higher inclination to make references compared to its civil and criminal law counterpart, the Greek Supreme Court. The latter has faced criticism from the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) for its lack of reasoning behind its refusal to make references.Footnote 63

The data on Greek preliminary references is also useful to understand whether lower courts feel pressure not to refer. Greece is a common law country with a “bureaucratic-type judiciary,” meaning that judges are highly independent from external political pressure because their selection and appointment procedures are determined by judicial self-governing bodies.Footnote 64 One could argue that this makes the Greek judicial system very hierarchical, and lower courts do not dare to refer because this might harm their evaluation—made by senior judges—and thus promotion. Evidence does not seem to support this hypothesis either.

As Table 1 shows, Greek lower courts and tribunals are the main source of preliminary references, followed by the Council of State.Footnote 65 To better understand whether submitting a preliminary reference was discouraged or seen as detrimental to a judge’s career, I interviewed a Greek administrative judge who sent two preliminary references to the CJEU, once as a judge rapporteur and another as a member of the panel. The judge denied any pressure from higher courts not to refer or any detrimental impact on their career after the reference was made: “I did not have any problem, obviously. I mean there is no kind of pressure or anything.”Footnote 66 Still, they admitted that not every judge wants to receive the attention that comes with submitting a reference: “I mean, many judges don’t want to attract so much attention to their work.”Footnote 67

Table 1. Total preliminary references from Greece. Source: Court of Justice Annual Report 2023.

The interview is in line with what has been found in surveys and in the literature, which is that some Greek lower-court judges might feel naturally intimidated by the task of making references. But this is not different from any other Member States and hardly explains the lack of references.Footnote 68

Lastly, another influential theory to explain national judges’ reluctance to refer is Wind’s argument positing that courts in majoritarian democracies are less familiar with supranational judicial review and thus less prone to refer than courts in countries with constitutional democracies.Footnote 69

This does not seem to apply to Greece, as judicial review is not alien nor new to the Greek judicial system. Although Greece does not have a constitutional court, it has a tradition of constitutional review that dates back to the 19th century, when the courts themselves “gradually and incrementally established the power of the judiciary to deny the application of unconstitutional statutes.”Footnote 70 In 1927, ordinary courts’ power of constitutional review was enshrined in the Greek Constitution.Footnote 71 Thus, “Greek courts generally follow a diffuse, incidental, and concrete system of review,”Footnote 72 meaning that ordinary courts, from the first to the last instance, are used to revise the legitimacy of the legislation by themselves, setting aside unconstitutional laws if necessary. To be sure, in the hierarchical Greek judicial system, the task of engaging in constitutional review is often left to the Council of State, which, for this reason, is considered “Greece’s constitutional court par excellence.”Footnote 73

In conclusion, a notorious decision not to refer by the Greek Council of State spread the belief that Greek judges are reference-adverse, but data do not point to a general reluctance to refer. Given its size, Greece has referred an average amount of cases, of which almost half were referred by the Council of State, which also serves as the last-instance migration and asylum court. Regarding lower courts, their reference rate, judicial culture, and hierarchical structure suggest that these might feel some sort of self-restraint, but probably not to the point of avoiding references.

III. No Access to (Higher) Courts

In a book chapter on migrant detention, two Greek administrative judges offer an alternative explanation for non-referrals. The chapter explains that “Greek administrative judges regularly encounter problems of interpretation of EU law when reviewing detention decisions”;Footnote 74 however, the Greek judicial remedies pose some “inherent constraints” to the possibility of making preliminary references.Footnote 75

Migrant detention is one of the areas where the Greek system shows more tensions with EU law, as confirmed by the fact that the EU Commission sent two letters of formal notice against Greece for failing to comply with the Return Directive 2008/115.Footnote 76 The possible infringements are many, ranging from the maximum duration of detention, the reasons to detain migrants, and the definition of “illegal stay.”Footnote 77

So why Greek judges haven’t made any references on migrants' detention? The inherent constraints mentioned by the two Greek judges consist of the procedural norms that regulate administrative detention and limit the ability of the judges to interact with the CJEU.Footnote 78 Two elements are critical in this respect: first, the decision of the first-instance court is not subject to appeal; second, the law requires that the decision is taken swiftly. Thus, “judges prefer to avoid the time and energy-consuming procedure of preliminary references and, instead, focus on the factual circumstances of the case.”Footnote 79

Access to appropriate judicial review is a problem also in asylum determination procedures, for two reasons. First, the asylum procedure in Greece has a four-layer structure, of which the first two are before administrative bodies, as it is displayed in Figure 3 below.Footnote 80 This makes Greece different from most of the EU Member States, where courts are competent to review first-instance asylum decisions.Footnote 81 In Greece, only after the application is reviewed a second time can the asylum seeker appeal and go before an administrative court and, eventually, the Council of State. It is disputed whether the first two bodies, being administrative, can be considered a “court or tribunal” under Art. 267 TFEU; but there are good reasons to think that at least the Independent Appeals Committee is so: it is independent, its decisions are subject to appeal before administrative courts, from 2017 to 2019 two of its members were administrative judges, and today all of its members are.Footnote 82 Still, the uncertainty around this issue may have discouraged members of the Committee from referring.

Figure 3. The structure of the Greek asylum procedure determination.

When talking about access to court, it is also important to consider that legal assistance to asylum seekers was not steadily provided in Greece. Although the EU Asylum Procedure Directive requires free legal assistance and representation at the appeals stages of the asylum procedure,Footnote 83 the Greek government struggled to set up a legal aid scheme for asylum seekers, which was introduced only in 2016 and started operating in September 2017, not without problems.Footnote 84 According to NGO reports, “Out of a total of 15,355 appeals lodged in 2018, only 3,351 (21.8%) asylum seekers benefited from the state-funded legal aid scheme.”Footnote 85 As we will see below, NGOs in part filled the gap left by the state but this free legal representation covers only the second administrative stage of the procedure, leaving the judicial parts out. Asylum seekers who want to bring their case before the administrative courts, and eventually the Council of State, must apply for legal aid under standard Greek law provisions, which by itself is a complex procedure and requires legal assistance.

A final practical obstacle was brought to my attention by an NGO member and lawyer; in the experience of the organization, after receiving the second negative decision on the asylum application, “the great majority of our clients leave. So, we don’t have a hearing in the end.”Footnote 86 The problem is that more than a year can pass between the filing of the appeal and the hearing before the administrative court:

So, in the meantime, people are leaving illegally. They go to Germany. […] Either they leave or they reapply for asylum. […] They would go for a subsequent application because Greece has this informal policy, super informal, that if you’ve been here for more than a year, they will examine the merits of your application. […] So, either they leave or they pull out of the judicial procedure because they want to reapply for asylum. And yes, it’s nine out of ten.Footnote 87

This means that for an applicant receiving a rejection, or an inadmissibility decision, it is easier to file a new application instead of going through the complex and costly judicial review proceedings. Data on asylum applications confirm this, showing an exceptionally high number of subsequent applications, as displayed in Table 2. Remarkably, data also show that the number of subsequent applications has grown exponentially in the last years, raising the question of whether this is a more recent phenomenon—and thus unable to explain the lack of references between 2008 and 2020.

Table 2. Asylum applications in Greece. Source: authors’ elaboration of Eurostat data and AIDA National country report – GreeceFootnote 90

This subsection so far has outlined several obstacles to access to courts that hamper migrants’ ability to reach Greek higher courts. However, it is important to recall two procedures provided by the Greek legal system which can be described as a highway to the Council of State. The first is the “pilot trial”: A procedure introduced in 2010 that allows courts to refer their case to the Council of State “when an issue of general interest with effects on a larger number of people is at stake.”Footnote 88 The procedure can be activated upon request of one of the parties in the proceedings or ex officio by a lower court.

The second procedure is an annulment action disciplined in Article 95 of the Greek Constitution. This enables litigants to petition directly before the Council of State to annul “enforceable acts of the administrative authorities for excess of power or violation of the law.”Footnote 89 The norm applies also to “executive organs’ omissions despite their obligation to act.”Footnote 91 This procedure has great potential for challenging administration acts and omissions, and indeed it has been used by political parties and NGOs in the migration field in the past.Footnote 92 Its potential to trigger preliminary references is further proven by the fact that one of the 2023 references was issued in a case brought to the Council of State via petition.

E. Internal Factors: The Presence of Altruistic Actors with Relevant Resources

The previous section has concluded that the Greek LOS is not closed, even if there are structural obstacles to the emergence of migration references. This section turns to the actors of the mobilization to test the second hypothesis of this study, positing that the absence of EU legal mobilization is due to a lack of altruistic actors or resources.

Many groups promote migrant rights in Greece. From online reports and conversations with Greek academics, I could identify eight leading organizations that regularly provide legal support to migrants:

-

○ The Greek Refugee Council (GCR)

-

○ Refugee Support Aegean (RSA)

-

○ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees – Greece (UNHCR)

-

○ Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society – Greece (HIAS)

-

○ Metadrasi

-

○ European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE)

-

○ Greek Helsinki Monitor

-

○ The Hellenic Action for Human Rights

UNHCR, GCR, and Metadrasi, have played a crucial role during the so-called refugee crisis. From 2015 to 2017, GCR and Metadrasi provided free legal assistance to thousands of asylum applicants arriving on the Greek islands, under a program partially funded by the European Commission and coordinated by UNHCR.Footnote 93 HIAS is an international NGO that operates in different countries to promote asylum seekers and refugees’ rights. RSA is a rather new organization that has been active since 2017; its focus on European legal strategies—both EU and ECHR-derived—makes it an excellent candidate for EU legal mobilization. Remarkably, RSA and GCR are the two organizations that obtained a preliminary reference from the Council of State in 2023. They are thus an excellent interviewee to ask: Why not before?

The remaining organizations are a bit different. ECRE is a European network of legal-focused pro-migrant organizations. They are a reference point for migration lawyers and activists. The Greek Helsinki Monitor and the Hellenic Action for Human Rights work in the field of minorities and civil rights, which led them to represent many migration and asylum cases before domestic and international courts.

This overview presents a wealth of organizations working for migrant rights in Greece. However, while the presence of a support structure is essential for legal mobilization to happen, it might not be enough. To mobilize EU law and convince national judges to refer, altruistic actors need specific resources.

From the outset, it is important to note that migrant rights defenders in Greece have often operated in crisis mode. While the government was trying to build an asylum system quickly,Footnote 94 NGOs such as Metadrasi were filling the gaps left by the state, helping the unprecedented number of people reaching Greece’s borders and islands, often in situations of overcrowding and underfunding. Since 2019, migration NGOs experienced further difficulties in carrying out their work because of growing hostility towards them; the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights Defenders noted that “Defenders active in this area, including lawyers and journalists, have been facing criminalization, intimidation, harassment and smear campaigns.”Footnote 95

To understand Greek actors’ perceptions, strategies and resources, I relied on interviews with members of the core legal team of the organizations listed above, for a total of nine interviews. This was not possible in the case of Metadrasi,Footnote 96 so I interviewed one of its former lawyers. All the people that I interviewed were Greek and spoke good English. The interviews were conducted via video call, except for two interviews conducted by phone. The interviews concerned two main topics: 1) Whether they have ever asked for a preliminary reference; and 2) Their connections to EU legal experts and academia. During the interviews, a third issue emerged: their preference for the ECHR Court. I will address each of these issues in order.

I. Altruistic Actors’ Perceptions of the Preliminary Reference Procedure

Lawyers and NGO members were eager to share the vast experience and knowledge acquired by defending migrant rights in Greece. However, they had little to say about preliminary references. Most of them have never tried to obtain a preliminary reference from Greek courts and some of them never considered this option. When I asked why, they gave me different reasons. Some of them confirmed that there are difficulties in accessing Greek courts, but they also added that they didn’t come across an issue that they wanted to submit via preliminary reference; plus, Greek judges would not refer anyway. Some of them said that they would rather go to the European Court of Human Rights.

For instance, RSA is one of the organizations that engages more with EU legal strategies.Footnote 97 Together with GCR, they brought to the Council of State the case that led to the first migration reference in 2023 regarding Turkey being a safe third country. However, they noted that:

[W]ith the exception of safe third country, we wouldn’t necessarily have done this for other types of cases […] We haven’t necessarily done this in other areas to the extent that we may not have found an issue that needs to be clarified, at least on the specific issues that we’re sort of working on. But very often we will have arguments that relate to the directives. So, to disapply domestic provisions, because they’re not in line with the directive directly invoking provisions of the directive. Also, for Greek judges, that’s not necessarily the easiest thing to sort of engage with. But indeed, I wouldn’t say that we have systematically incorporated references in our litigation.Footnote 98

The other applicant in the case that led to the 2023 migration reference is GCR. They are “the first and oldest Greek NGO which provides legal assistance to persons in need of international protection”Footnote 99 and they are the organization that engaged the most with the preliminary reference procedure. During the interview, the GCR member mentioned two attempts to obtain a reference, one in 2014 and another in 2022.Footnote 100 The 2014 attempt concerned detention, which is decided by first-instance administrative judges, against whose decision there is no remedy. According to the interviewee, “it was maybe too much for the first-instance court to send something to Luxembourg.”Footnote 101 More generally, the GCR member believes that there is a general reluctance to refer by Greek courts and in particular by the Greek Council of State, allegedly because migration “is too close to politically sensitive issues such as borders and national security”; or because the judges “don’t really feel that they need to do that; they feel capable of replying.”Footnote 102

One episode corroborated Greek migrant rights defenders’ perception that Greek courts are reluctant to refer. We must go back to the heated years of the refugee crisis. More specifically, in 2017, when the Council of State delivered its (in)famous decision not to refer regarding the legitimacy of the EU-Turkey Statement, already mentioned in Section D.II. At that time, the Greek Asylum Service was declaring inadmissible all the asylum applications submitted by Syrian nationals, in compliance with the Statement.Footnote 103 Metadrasi and GCR were in charge of providing legal aid to asylum seekers on the islands,Footnote 104 so they started appealing these rejections. According to a former Metadrasi lawyer, they inserted in each appeal the request to make a preliminary reference to the CJEU: “We had like three standard paragraphs in the end that we were putting in our memos.”Footnote 105 This was confirmed by another lawyer formerly working for GCR on Samos: “It was almost a template argument that we used in our submissions as GCR.”Footnote 106

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these template requests for preliminary reference were ignored by the Asylum Appeals Committees. However, two of the Syrian cases were further appealed and brought to the Council of State; here the Syrian applicants were represented by two of the best-known Greek migration lawyers—Giota Massouridou and Marianna Tzeferakou—who reiterated the request to have the case referred to the CJEU, probably in a more articulated way.Footnote 107 This time, the Council of State did not ignore their request but, by a slim majority, refused it nevertheless.

The Council of State’s decision was eagerly awaited by all migrant rights defenders in Greece, including legal aid lawyers on the Greek islands. When the news of dismissal arrived on the islands, it left a lasting impression on the possibility of reaching the CJEU:

We had this feeling that you know, it’s not an open road; in general, that what we were asking for in most of the cases was rejected. […] I think this was especially after the first Syrian cases when they were rejected by the Council of State. So, I think that after this, you know, all of us were very disappointed.Footnote 108

I remember we were all on the islands expecting to see how these cases would be decided, to see how we continue litigation on the islands. And when the decisions came out in September 2017, I remember that we said: okay, if this is the response of this Council of State, we’ll continue our litigation to protect people individually at least. I remember this was the feeling at the time.Footnote 109

It is relevant to say that, when talking about preliminary references, almost all the interviewees mentioned the 2017 Council of State’s decision. In NGOs’ account, this decision was a critical juncture. It shaped their perception of Greek courts, strengthening their conviction that they are reluctant to refer migration cases:

The discussion at that time in 2017 confirmed this fear that, because migration is such a political issue, judges are careful. And reluctant. […] we knew migration is a very political area and we knew this can affect judicial action. And we felt that this was confirmed by those decisions.Footnote 110

When I asked a GCR member why they thought that the Council of State changed its position and decided to refer in 2023, they replied that this has to do with political considerations too. First, the legal issue at stake was different, as it was no longer about the definition of a safe third country but whether Turkey should be removed from the safe third country list because it does not allow readmissions. Second, the factual situation was different as there is a considerable number of Syrians in limbo because they cannot be readmitted. Third, the Council of State realized that the EU-Turkey Statement was not a solution for Greece, so it should no longer shield it from judicial review:

To my understanding, back in 2016, there was the idea that the EU-Turkey statement could be a solution to the refugee crisis in Europe. Now, we don’t have the same understanding after seven years of applications. I mean, it’s well known that despite the EU-Turkey statements, the number of applicants that have been indeed readmitted to Turkey is really low. […] So, I think that the Council, the judges, were not feeling so much the stress that they have to deal with a very hot political issue.Footnote 111

These interviews give the general feeling that civil society actors see Greek courts as too sensitive to political considerations and thus willing to shield Greek law from supranational judicial scrutiny.

It is useful to complement these interviews with the view of a Greek administrative judge who drafted a preliminary reference to the CJEU and was a member of the panel that referred another question to the CJEU. The court referred ex officio: “[T]he lawyer never proposed to actually refer the case to the CJEU. She had no idea that we were going to do that. She didn’t even think of saying that there is some problem, some conflict with EU law at that point.”Footnote 112 I then asked the judge whether, in Greece, lawyers tend to submit legal memos that can be used as a basis for preliminary reference requests, and this was the answer:

No, it can be the case before the Council of State. I’m not so sure about that. […] Normally in our cases we don’t get that. […] Many of the applicants come with legal aid, so lawyers are definitely not specialized. They’re just random lawyers who have no idea what they’re talking about and they make a lot of mistakes, too. So, it’s far, far from actually being able to draft a preliminary reference. They have much bigger problems with their appeals. And even specialized lawyers from NGOs usually have a huge backlog, a huge workload. So, they cannot really spend that kind of energy doing that. They sometimes get somebody to draft a good legal argument and that is repeated over and over and over again. But it rarely is really a question of referring something to the CJEU.Footnote 113

To sum up, we can say that Greek civil society actors have tried to mobilize before the CJEU only sporadically. One of the reasons lies in migrant right defenders’ perception that Greek judges are reluctant to refer, in a way similar to what was found by Van Der Pas in the Netherlands.Footnote 114 Here in Greece, such conviction seems in part linked to the belief that judges follow politico-strategic considerations that affect their judicial receptivity. The perception of a closed legal opportunity structure was strengthened by the 2017 decision of the Council of State, which left a lasting impression on lawyers and activists. However, this is not all the story, as next subsections will show.

II. The Lack of EU Legal Expertise

Migrant rights defenders often rely on little financial resources. They have little funding, small legal teams, and face unfriendly or hostile government policies. Despite all this, from small offices with one or two lawyers, they manage to mobilize and reach the Court of Justice. This is largely thanks to their non-material resources, among which the availability of EU legal expertise occupies a special place. This expertise can be in-house, that is, provided by Eurolawyers among their staff, but often it is provided for free by external allies, like EU law academics.

EU legal expertise is valuable not only for enhancing litigants’ understanding of EU law and ‘ghostwriting’ preliminary questions.Footnote 115 EU legal expertise is also indispensable to show openings in the EU LOS and raise altruistic actors’ legal consciousness. For instance, when the Greek lawmaker decided that migrants could be detained on public security grounds pending removal, EU legal experts would understand that this is an opportunity for contestation via the Return Directive, which does not allow administrative detention for reasons of public security.Footnote 116

In Greece, there are only three law schools and, at the time of writing, none of them offers a course in EU migration law. When I asked migrant rights defenders in Greece whether they ever received help from legal scholars or EU law experts, they replied in the negative. The GCR member told me:

In the drafting? Not really, because it’s in Greek. And I mean, no, we don’t have the support of academics from Greece, because they are actually… there are not a lot of people that are dealing with such issues in Greece. […] We do have contacts with the Greek academia. However, the Greek academia, they are not really involved in issues of EU law on asylum. They are more discussing, you know, more geopolitical issues. So, things that have to do with integration and the understanding of the refugee phenomenon or things like that; but not as such, the interpretation of Article 38 on safe third country and blah, blah.Footnote 117

HIAS confirmed this:

[I]t’s not that we have been approached by people to collaborate. I don’t think anybody has done this. […] Because we don’t have law clinics in Greece. It’s not really a thing either. So, I would say that we have collaborated more with foreign academics than Greeks.Footnote 118

During the refugee crisis, time constraints and resources might have played a role in the NGOs’ capacity to think strategically and collaborate with academics. In the words of a Metadrasi lawyer providing legal aid on one of the Greek hotspot islands during the most difficult years between 2016 and 2017:

I think that the general problem in Greece is that, you know, everything was so massive, so many cases. So, you didn’t have the time, you know, to spend a lot of time to examine the case from different angles and aspects. You were supposed to do everything, to react very quickly. And especially in the border procedure, one day, the applicant was there and the other one, after the rejection, he disappeared. You didn’t know where they went. So, maybe this also responds to your question why we didn’t have like a collaboration with academia, because we didn’t have the time to, we didn’t have the luxury.Footnote 119

ECRE in the last few years has tried to cover this gap and provides expert opinions to Greek organizations. According to its member, the NGOs working in Greece have a very good knowledge of EU law and procedures, but their financial constraints might impact their ability to get training: Greek lawyers “work under bad conditions” with little access to training and travel to do networking and exchanges as it is normal in other countries.Footnote 120

III. The Preference for an Alternative Venue: The ECtHR

Through the interviews, I could detect a last reason for altruistic actors’ lack of engagement with the CJEU: Their preference for the Strasburg Court, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). When I asked the Greek Helsinki Monitor whether they have ever tried to persuade a Greek judge to refer, they replied that they never did, because it was difficult to reach Greek courts; but they immediately added: “By the way, I’m not even sure that, if we reached somewhere, we would have gone there. Because we have the case law of the European Court [of Human Rights].”Footnote 121 Another experienced migration lawyer told me that, while they represented more than 5000 applicants before the ECtHR, they rarely asked for a reference from Greek judges, as they are less familiar with the procedure.Footnote 122

While it is common to have lawyers specialized in applications before the ECtHR, and thus less familiar with other courts, in Greece this seems to be a general attitude. Other interviewees told me that they see the ECtHR as a “more reachable” court.Footnote 123

The interview with a staff member of the Greek office of UNHCR confirmed this. They explained to me that, although in Europe their “judicial engagement” strategy involves intervening before both European courts, in Greece they mainly focus on the ECtHR.Footnote 124 Moreover, the general lack of preliminary references from Greece prevented the UNHCR from filing online submissions to the CJEU as they do in cases referred from other countries.Footnote 125

The predilection for the Strasburg Court resonates with Greece’s history of litigation for migrants and minorities before the ECtHR. Although Greece compared to other countries such as the UK “lacks a tradition of public interest litigation,”Footnote 126 it has a long tradition of litigating before the ECtHR, including for migrant rights. According to Anagnostou, “[i]n Greece, from 2008–2009 onwards, a group of lawyers with a progressive and/or leftist orientation began to systematically bring migrant-related complaints before domestic courts and in the Strasbourg Court to challenge restrictive immigration detention practices and highly deficient asylum procedures.”Footnote 127 Interestingly, in this case, the lack of access to courts and judicial remedies helps lawyers, as they easily pass the “exhaustion of remedy” condition.Footnote 128

The ECtHR and the CJEU are not equivalent nor alternative; they have different mandates and jurisdictions. When it comes to asylum, however, there is a lot of overlap between the two courts, because the EU asylum legislation is to a great extent derived from international and human rights law. Thus, looking at the number of ECtHR asylum judgments given in proceedings against Greece can be revealing; while until 2023 Greece lacked asylum references, it abounded with cases before the Strasburg Court. According to the DICTA database on the ETCtHR asylum judgments, among the EU countries, Greece is second only to France, displayed in Figure 4.Footnote 129 It is worth noting that, according to the data available, many of the ECHR cases against Greece pre-date the so-called refugee crisis and the 2017 Council of State’s decision not to refer, as displayed in Figure 5;Footnote 130 this excludes that collective actors went to Strasburg in reaction to Greek courts’ reluctancy to refer, but it is rather a pre-existing legal strategy.

Figure 4. Judgments decided by the ECtHR in the field of asylum and refugees from 1989 to 2023. Source: DICTA database elaborated by the author.

Figure 5. Applications against Greece brought before the ECtHR in the asylum field. Source: DICTA Database elaborated by the author.

Why then Greek migrant rights defenders seem to prefer Strasburg over Luxembourg? Arguably, the ECtHR takes longer to issue a judgment—up to ten years—and, depending on the issue, it applies equal or lower standards than the CJEU.Footnote 131 Also in terms of the effectiveness of its judgments, the ECtHR lacks the systemic impact of preliminary rulings, which are binding on all the Member States’ courts. While it is true that the same violation can be sanctioned before different bodies and through different remedies,Footnote 132 it is also important to notice that some claims can be brought only before the CJEU. For instance, the ECtHR cannot rule on the legitimacy of actions and laws of the EU, as this is not part of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Many of these ECHR applications have been brought by the lawyers and NGOs that I have interviewed, and they offered two important insights. First, the ECtHR is better equipped to address human rights violations with no remedies before domestic courts, contrary to the CJEU. An eminent example is the case of illegal and violent pushbacks of migrants by sea: The Greek authorities failed to investigate this practice, leading NGOs to bring “an avalanche” of applications to the ECtHR.Footnote 133 A second factor is the high reputation of the ECtHR in Greek legal culture. In the words of an ECRE member:

I remember even as a child hearing about the European Court of Human Rights in the news more than the CJEU. And hearing about this ability for a person to go there and remedy their own personal injustice, and the financial compensation that the Court could grant in the judgment. […] Still now it’s kind of like this, the Court is this almost mythical being that will save you when Greece fails you. And this is a very common mentality in Greece; that the Greek state constantly failed Greek people in many ways.Footnote 134

This is a manifestation of what Tilly calls the “limited repertoire of collective actions”:Footnote 135 Greek migration lawyers and NGOs’ preference for Strasbourg over Luxembourg is not always motivated by strategic considerations, but it is rather engrained in the way in which they have been fighting for migrant and minority rights for years. They are used to a specific type of international litigation, which has the advantage of familiarity, and they only recently started experimenting with different forms of actions.

F. Conclusion: Lack of Access, Lack of Experts, and the Strasburg Predilection

This article investigated Greece’s persistent absence of migration and asylum preliminary references. Despite being crossed by important migration flows since 2009, Greece’s legal framework and reception system consistently fall short of EU standards. While EU law and the preliminary reference procedure theoretically offer avenues for challenging national migration policies and strengthening migrant rights, these opportunities remained largely theoretical, failing to materialize in practice. The article raises the crucial question: Why? Is this inertia attributable to structural impediments, such as issues with judges and norms, or subjective factors involving lawyers and pro-migrant movements? By analyzing the legal and social context, the article uncovers notable barriers to accessing courts in Greece. But paradoxically, even when some avenues existed, stakeholders rarely capitalized on them, missing opportunities to initiate preliminary references.

The article tested two hypotheses. The first refers to the EU LOS: Have the Greek legal framework and national courts hampered the ability of movements to mobilize in court and reach the CJEU? Data suggest that, in general, Greek—administrative—judges are not structurally reluctant to refer. However, especially in the detention and asylum fields, there are important obstacles to access to courts that can make it difficult for groups to reach apex courts. Still, there are procedures, such as article 95 of the Greek Constitution, which can be used to directly reach the Council of State. Overall, we cannot consider the EU LOS completely closed in Greece, and thus this hypothesis is confirmed only in part.

The second hypothesis refers to internal factors and posits that actors do not have the necessary resources to mobilize. Relying on the interviews, the paper traces how actors perceive the EU LOS, which is important for the mobilization to happen.

What emerges is that, until recently, Greek migrant rights defenders have not relied systematically on the preliminary reference procedure to contest national law and practices. They either did not detect situations where EU law could be usefully mobilized before the CJEU, or they thought that, in any case, Greek judges would be reluctant to refer. This can be due to the lack of a stable collaboration with EU legal experts and EU law academics, who in other countries have been crucial promoters of preliminary references. Finally, the interviews revealed a predilection of Greek migrant rights defenders for the Strasburg court, where they often bring cases. Greek NGOs have a long tradition of litigating before the ECtHR, while the CJEU remained a rather unfamiliar court. Overall, these findings suggest that the lack of mobilizing actors’ initiative to seek preliminary references partly explains the lack of references.

This article contributes to the fields of legal mobilization, strategic litigation, and preliminary references in three ways. First, it addresses a gap in the literature by examining a case of non-mobilization, an aspect often overlooked but critical for identifying factors that we take for granted in positive cases, such as access to courts. Second, the study goes beyond judges alone and encompasses lawyers and NGOs in its analysis, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the barriers to legal mobilization. Third, the findings highlight the importance of considering actors’ perceptions, legal consciousness, and traditional repertoires of action. In contrast to other Member States, Greece lacks the support of EU legal experts who could guide movements in utilizing EU legal strategies effectively. This insight underscores the need for greater awareness and capacity-building initiatives to leverage EU legal mechanisms effectively in Greece’s migrant rights advocacy efforts. Even if EU law offers rights and legal avenues that can shift the balance of powers, if such tools remain unused this is to no avail.

Recent events point to possible changes. As mentioned, in 2023, Greek courts finally made two references in the asylum field. The first was made ex officio by a first-instance court; the second was referred by the Council of State as the result of a strategic effort by two Greek NGOs: GCR and RSA. The CJEU judgment in this second case was recently published and supports the view of the NGOs.Footnote 136 As Miller showed for Denmark, positive judgments by the CJEU have the potential to shape national courts and civil society’s strategies, exposing the power of using EU law to challenge the status quo.Footnote 137 In the case of Greece, we still do not know how the CJEU will respond to the second preliminary reference, but already this first positive judgment might show civil society actors the potential of EU litigation and that Greek courts are not reluctant to refer, after all, thus changing their perceptions on judicial receptivity.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank all the interviewees who generously contributed to this study. I am grateful to the editors of the special issue, Pola Cebulak, Marta Morvillo, and Stefan Salomon, for inviting me to write this contribution and for organizing two great preparatory workshops in Amsterdam. I am grateful to the participants in the NYU Fellow Forum (New York, 2022), the Legal Mobilization workshop (Oslo, 2023), the Nuffield Socio-legal workshop (Oxford, 2023), the ECPR Law and Courts workshop (Oslo,2023), the Globalization and Law Network (Maastricht, 2024), and to all the MOBILE crew for their valuable feedback and help. Thanks to Dia Anagnostou, Alezini Loxa, Afroditi Marketou, Nikos Papadopoulos, Urška Šadl, Lilian Tsourdi, and Sophia Zisakou for their generous help and suggestions. All errors are mine.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.

Funding Statement

There is no specific funding associated with this Article.