Introduction

In 2021, Renmin University of China conducted an excavation at the site of an East Syriac church (Figure 1) located north of the ruins of Tangchaodun 唐朝墩 ancient city in Qitai County, Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture, within the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Map 1). Located within the central area of the nave, in the north aisle of the church, one can see a rectangular structure constructed out of adobe (Figure 2). The raised platform can be dated to the period of the Gaochang Uyghur Kingdom, between the tenth and fourteenth centuries, at which point the Tangchaodun site was abandoned.Footnote 1

Figure 1. Plan of the Tangchaodun Church site.

Figure 2. Bema in the Tangchaodun Church site (southwest–northeast).

Map 1. Ecclesiastical sites in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Gaochang Uyghur period.

According to the architectural terms given by Īshōʿyahb I (Figure 3)Footnote 2, also with reference to J. M. Fiey’s restoration of the church building plan of Chaldean-rite Christianity (Figure 4),Footnote 3 it can be identified that the platform is a fundamental liturgical furnishing of East Syriac Christianity, namely a ‘bema’, serving as the place at which the Liturgy of the Word, which is the first part of the Sanctification, is conducted.

Figure 3. Church structure according to Īshōʿyahb I.

Figure 4. Plan of Chaldean Church (Légende du plan de l’ Église Chaldéo-Nestorienne).

For the detailed structure of the Tangchaodun bema, the central part of the eastern wall features a staircase that gives access to the elevated platform, with a heptagonal column on each of the south-east and north-east sides. At the symmetry point, a niche is carved inside the central part of the western side of the bema, flanked by two symmetrical columns. Located at the base of the central niche is an octagonal pedestal, and the walls on either side bear discernible remnants of mural paintings and inscriptions. The Tangchaodun bema is characterised by the presence of four shallow niches (or frames) on both its south and north walls. A further crucial characteristic is the central part of this elevated platform, which contains an arched doorway connecting the north to the south side.Footnote 4

The emergence of the Tangchaodun bema is rooted in the liturgical system of Syriac Christianity. Meanwhile, as a product of the Church of the East within the transmission route from Syria—Mesopotamia (Persian Gulf)—Central Asia—Xinjiang, its architectural form, detailing, and iconography reflect the localised adaptation of cultural exchange. This article addresses the following key issues from this perspective:

1. Within the chronology of the Syrian bema tradition, what are the typological classification and structural characteristics of the Tangchaodun bema?

2. How does the Tangchaodun bema, along with its associated liturgical furnishings, reflect the East Syrian liturgical tradition and the symbolic function of sacred space?

3. In what ways does the Tangchaodun bema embody both Syriac Christian liturgical practices and localised adaptations—architecturally and iconographically—amid the eastward transmission of the Syrian bema?

Through a comparative analysis of bemata across Syria, Mesopotamia, and Central Asia, this article seeks to demonstrate the significance of the Tangchaodun bema and to enhance the understanding of how East Syrian Christian liturgical furnishing was transmitted and adapted across cultural frontiers.

Tangchaodun bema in the Syriac Christianity tradition

Transition and evolution of bema types from Syria to Mesopotamia

As a key architectural feature in Syriac Christian churches, the bema not only coordinates with other furniture but also adheres to fundamental liturgical principles. The main focus of this section is to establish the chronology of bema-tradition development, set within the context of Syriac Christianity, across the spatial range from Syria, Mesopotamia, to Central Asia and Xinjiang, with consideration of cross-regional architectural traditions. The appearance of the Tangchaodun bema is ‘inlaid’ in the sequence and, through this, examines the localisation of East Syriac Christianity.

Classification and characteristics of the ‘north-western Syria-type bema’

In the early twentieth century, H. C. Butler’s systematic survey and documentation of churches and monasteries in northern Syria introduced the terms ‘exèdre’ (exedra) and the Syrian-style ‘ambon’ to describe the bema.Footnote 5 Building upon early fieldwork, J. Lassus’s foundational researchFootnote 6 and G. Tchalenko’s influential monographFootnote 7 played a vital role in popularising the term ‘bema’. Further research by R. TaftFootnote 8 on the attributes of a bema and its associated liturgical practices advanced the scholarly understanding of its significance.

According to Taft’s four categories of church distribution, a bema is commonly found in churches of northern Syria, particularly in the Syrian Limestone Massif. The standard form of the bema in this area is straight-sided and horseshoe-shaped, with origins traceable since the fourth-century Antioch region. In addition, updated learning suggests that similar bema forms found within the territory of Syria II should also be considered as part of the system.Footnote 9

Tchalenko mapped the distinctive features of horseshoe-shaped bemata in Syria, analysing their architectural elements.Footnote 10 Following his logic, this part proposes to uniformly categorise these forms as the ‘north-western Syria-type bema’,Footnote 11 which could be subdivided into three types: Type A (Figure 5a), characterised by a podium closest to a semicircle; and Type B (Figure 5b) and Type C (Figure 5c), which typically feature a rectangular-like main structure in the east, with a ‘bema-throne’Footnote 12 set in the semicircular west part. From the fifth to sixth centuries, these structures evolved from wood to stone, becoming standardised within the Diocese of Antioch. The Type C north-western Syria-type bema—the most complicated due to its three-part design—provides remarkable insights into the specific functions of the bema within Syrian liturgy. Moreover, as this form spread eastwards into the Syro-Mesopotamia frontier region, significant formation changes occurred, ultimately influencing the architectural styles of East Syriac Christianity, including the Tangchaodun bema in Xinjiang, as discussed later in this article.

Figure 5a. Type A north-western Syria-type bema in Jerade Church.

Figure 5b. Type B north-western Syria-type bema in Qalb Loze Church.

Figure 5c. Type C north-western Syria-type bema in Holy Cross Church, Resafa.

Liturgical system and ‘cosmological symbolism’ in sacred space

The design of the bema aims to facilitate the weekly re-enactment of the crucifixion and resurrection through its role in the Liturgy of the Word.Footnote 13 This tradition, derived from the so-called ‘Nestorian liturgy’,Footnote 14 is compatible with the architectural layout of Antioch and seeks to express theological concepts through symbolic spatial arrangements.Footnote 15

Archaeological evidence from Syria suggests that the fifth and sixth centuries marked the maturation period for Syrian church architecture. During this time, architectural focus shifted towards integrating the sanctuary with other functional areas, leading to a distinct style that set it apart from ‘Roman models’.Footnote 16 It is notable that the semicircular apse structureFootnote 17—a distinctive feature of Syrian church architecture—became standardised during this period. Concurrently, the ‘horseshoe-shaped bema’ (Type A and Type B) had also attained full development by at least the mid fifth century.Footnote 18

Drawing on Jewish prototype cosmological symbolism, the bema, as a symbol of sacred space, contributes to the overall liturgical space system alongside other areas. The sanctuary represents heaven, the qestroma corresponds to paradise, the nave symbolises the earthly church, and the bema embodies the earthly Jerusalem.Footnote 19

Based on both archaeological evidence and historical records, it can be inferred that the core design principle of ‘bema mirrors the apse, replicating its form’ was influenced by the early Antioch Church. The close correlation between the shape of bema and apse creates a visual ‘mirroring relationship’,Footnote 20 reinforcing its liturgical function and positioning church architecture not merely as a place for religious activity but as a tool for educating believers and strengthening Christian faith.

Origin, distribution, and characteristics of the ‘eastern-type bema’

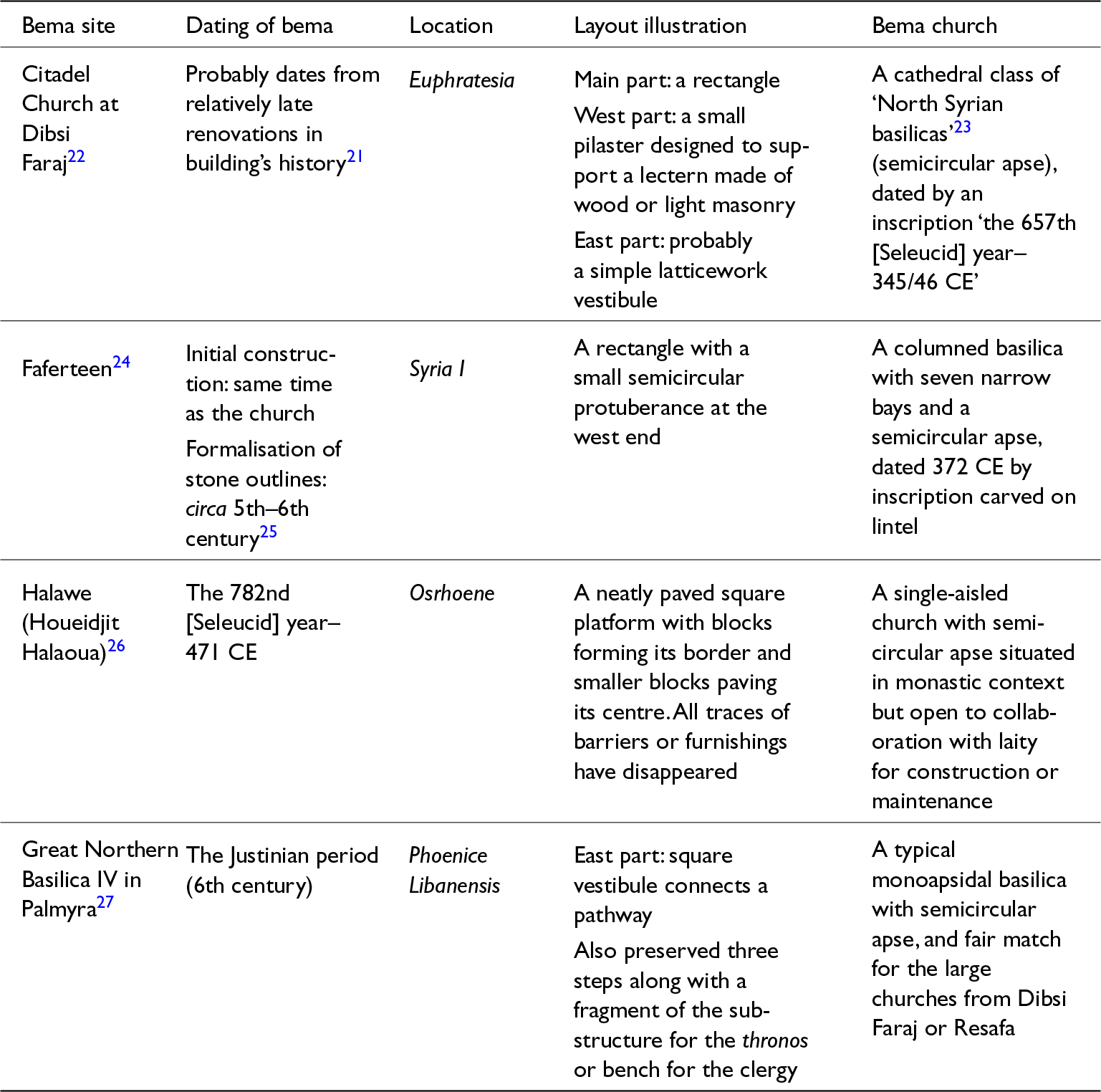

In addition to the north-western Syria-type bema, archaeological excavations since the twentieth century have revealed four rectangular/square-shaped bemata in north–central Syria (see Table 1 and Figures 6a, 6b, 6c, and 6d). Given the cultural context of Syro-Mesopotamia (central Syria), this article uses the term ‘eastern-type bema’, emphasising its geographical characteristics rather than confessional affiliation.

Figure 6a. Plan of Faferteen Bema Church.

Figure 6b. Plan of Citadel Church at Dibsi Faraj.

Figure 6c. Plan of Halawe Bema Church.

Figure 6d. Plan of Great Northern Basilica IV in Palmyra.

Table 1. Rectangular/square-shaped bemata found in Syro-Mesopotamia

Placing the rectangular/square-shaped bema in its historical and geographical context, it is clear to find that, except for the Faferteen Church site,Footnote 28 Dibsi Faraj and Houeidjit Halaoua bemata are within the geographical and cultural sphere of the Middle Euphrates region (see Map 2).Footnote 29 Based on the rough north-eastern limes of the Middle Euphrates—Palmyra (central Syria), the westward and eastward development of the bema diverged. In regions distant from Antioch, such as Euphratesia and Osrhoene, the eastern-type bema retained the essential symbolic element of the north-western Syria-type bema—that is, the so-called ‘bema-throne’—but transformed the horseshoe shape into a rectangular form.

Map. 2. Square/rectangular-shaped bemata in the Middle Euphrates region.

Since antiquity, the Syro-Mesopotamia region, in which the eastern-type bemata are distributed, has been a borderline between Rome and Persia.Footnote 30 The religious architecture in this region blends Sasanian artistic traditions with native Semitic styles, creating a second Christian language parallel to the West Syrian tradition.Footnote 31 Persian influence is evident in church buildings from Tur ‘AbdinFootnote 32 to the Iraq–Persian Gulf.Footnote 33 Although there is no direct archaeological evidence of the developmental sequence of the square/rectangular-shaped bema in Syro-Mesopotamia, as a key liturgical furnishing centre located in a church layout, the form of the eastern-type bema may also had been permeated by Persian style—particularly the ideal preference for a square outline in core areas, drawing from both secular buildings (such as royal palaces) and sacred structures (such as Zoroastrianism fire temples).Footnote 34

Evolution and spread of the eastern-type bema tradition

Building upon the distribution, structural features, and cultural factors of the eastern-type bema, tracing its evolution path on the Church of the East reveals a key liturgical and architectural intersection: the Type C north-western Syrian-type bema, exemplified by the Basilica of the Holy Cross (Basilica A) in Resafa (Figure 7). Resafa—also known as Sergiopolis, named after Saint SergiusFootnote 35—offers critical evidence. Its bema includes an underground chamber for housing relics and a central ciborium for their ritual display during festivals.Footnote 36 Similar relic-veneration features appear in other Type C bema sites, such as Seleucia Pieria and Qausiyeh (the martyrium of St Babylas).Footnote 37

Figure 7. Plan of Holy Cross Church in Resafa.

Uniquely, the Basilica of the Holy Cross also retains both the synthronon in the apse and bema (Cathedra), making it the only known site at which these two liturgical devices coexist. This dual presence provides compelling evidence for transformation of the Antiochene bema tradition during the sixth to seventh centuriesFootnote 38—preserved, notably in Resafa, geographically distant from the Antiochene core region.

By the sixth century, the Resafa ecclesiastical complex had become a major cross-cultural and inter-religious pilgrimage centre, drawing worshippers from Byzantine, Sasanian Persian, and Arab communities.Footnote 39 In this context, the Syrian bema tradition—diverse in its architectural expressions (namely the rectangular-shaped Type C north-western Syria-type bema or the rectangular eastern-type bema) incorporating Persian architectural features—likely spread eastwards along the pilgrimage route of palmyra–Resafa–Disib Faraj to Mesopotamia.Footnote 40

Mesopotamia as a convergence area: regional variations in the bema and the related liturgical system

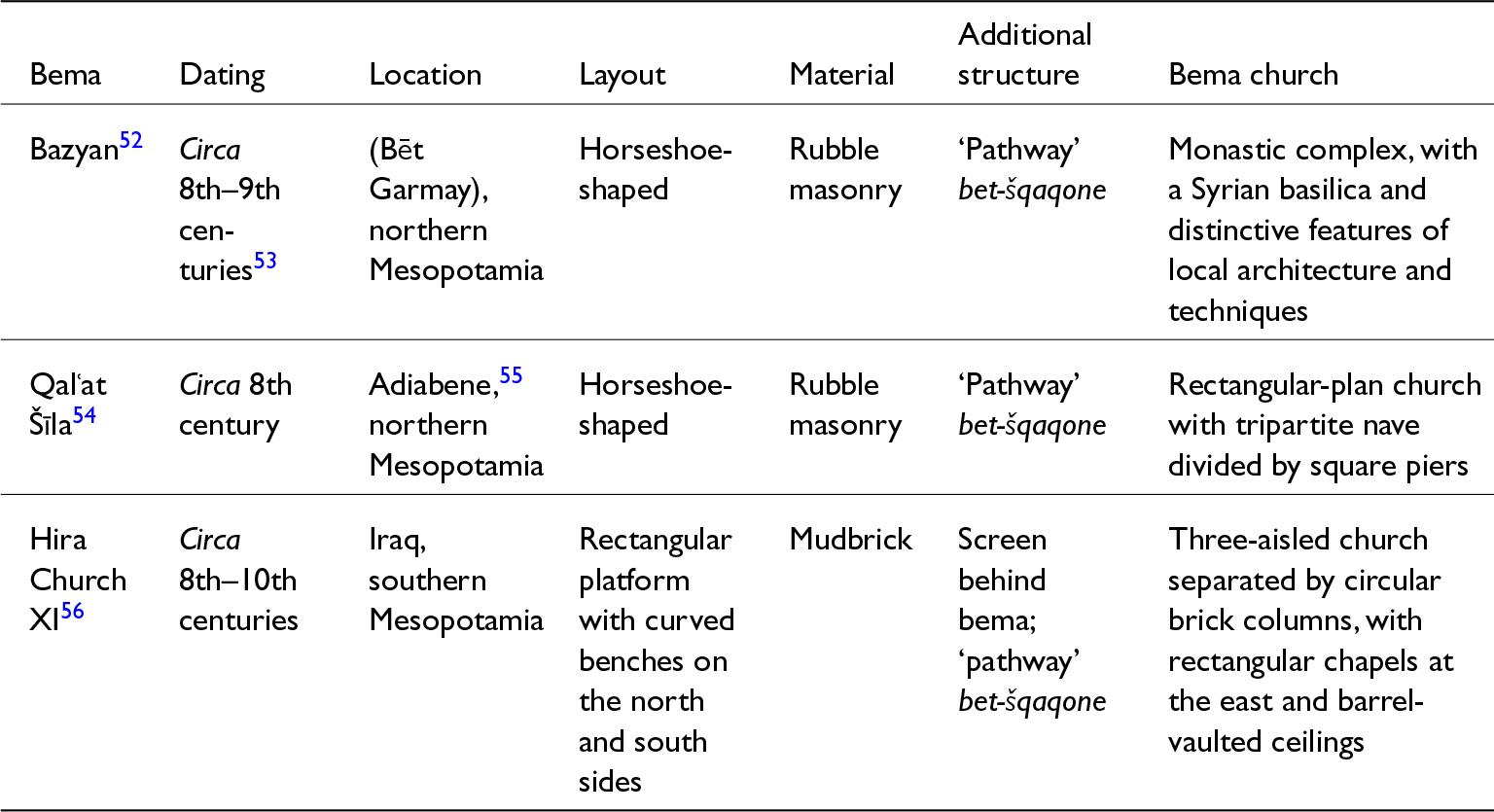

From the Sasanian period onwards, Christian traditions in Mesopotamia, including the Church of the East and Miaphysite Christianity, flourished under a confluence of cultural and theological interaction (see Map 3a and Map 3b).Footnote 41 Currently, three known cases of a bema belonging to the East Syrian tradition have been confirmed (see Table 2 and Figures 8a, 8b, 8c, and 8d). Analysing the similarities and differences in bema churches between northern and southern Mesopotamia provides a significant perspective into how architectural form and its associated liturgies were localised, and how they ultimately extended eastwards to Central Asia and Xinjiang.

Figure 8a. Plan of Bazyan bema church.

Figure 8b. Plan of Qalʿat Šīla bema church.

Figure 8c. Plan of Hira Church XI.

Figure 8d. Bet-šqaqone in Hira Church XI.

Map 3a. Syriac Christianity sites in northern Mesopotamia. Source: Amin Ali and Brelaud, ‘Churches’ building in Northern Iraq, fig. 1.

Map 3b. Syriac Christianity sites in southern Mesopotamia.

Table 2. East Syrian tradition bema sites in Mesopotamia

The shape and spatial organisation of bema churches across northern and southern Mesopotamia reveals regionally distinctive patterns rooted in hybrid indigenous contexts.

Bema churches in northern Mesopotamia exhibit a ‘distinct borderland identity’.Footnote 42 In addition to common characteristics found throughout Mesopotamia, regions closer to the Byzantine–Persian border incorporate more pronounced ‘Western elements’ in their church designs.Footnote 43 The bemata at Bazyan and Qalʿat Shīlā, for instance, conform to the Type A north-western Syria-type bema, shaped by the centre the of Diocese of Antioch–Edessa–Tur ‘Abdin–Mesopotamia ecclesiastical expansion network.Footnote 44 The Gola Bema site in Tur ‘AbdinFootnote 45 further supports the diffusion of this Syrian tradition. However, church layouts in this region frequently diverge from the Antiochene formula of ‘bema mirroring the apse’. Instead, they feature rectangular sanctuaries paired with semicircular or horseshoe-shaped bemata, echoing Persian architectural conventions.Footnote 46 As for the southern counterpart, Hira Church (Mound XI) in the Persian heartland,Footnote 47 with its eastern-type bema and near-square (cruciform-shaped) sanctuary, more clearly demonstrates the normative East Syrian theology.

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that, beyond the shape of the bema, a more significant divergence occurred in how the bema-related liturgical office/service and ‘sacred context’ formed in northern and southern Mesopotamia.

According to East Syrian ecclesiastical law, the bema is restricted to the cathedral-based service and absent from monastic rituals.Footnote 48 This aligns with archaeological findings from northern Syria, which consistently reflect this usage. Yet, in northern Mesopotamia, ecclesiastical complexes increasingly blurred the boundaries between two sets of liturgies. For example, the Bazyan bema, situated within a monastic church, allowed lay participation in both parish and monastic services,Footnote 49 which is evidenced by architectural modifications for pilgrimage, such as the prominent apse that may have functioned as a Bēt sāhdē—that is, a martyrium housing relicsFootnote 50—suggesting that Bazyan’s saint-veneration function paralleled that of Resafa. Despite adherence to early traditions, the East Syrian cathedral office may have occasionally ‘retreated to monasteries’ as did its counterpart Syrian Orthodox in northern Mesopotamia to preserve its liturgical heritage amid periods of intense inter-religious conflict involving Muslim and Christian groups.Footnote 51

In contrast, the southern heartland of the Church of the East maintained a clearer distinction between parish and monastic liturgy systems. The Hira XI Bema Church exemplifies the former, while the latter is represented by monastic churches built in the seventh/eighth to ninth centuries (such as those at Kharg in Iran,Footnote 57 Al-Qusur in Kuwait,Footnote 58 and Ain sha’ia in IraqFootnote 59) that omitted bemata and qestroma due to simplified hierarchy and liturgical practices.Footnote 60 These churches, through their baptistery and reliquary, as well as spatial design of central and side aisles, incorporated a ‘pilgrimage flow design’ that allowed pilgrimage activities to occur without disrupting the monastic daily routine.Footnote 61

Despite local variation, one feature exhibits remarkable consistency across Mesopotamia: the bet-šqaqone—a processional passage linking the bema to the sanctuary, symbolising a bridge between the heavenly and earthly realms.Footnote 62 Its substantial origins lie in the ambo with the solea of Byzantine liturgical architecture in Greek-speaking Syria. In Mesopotamian churches, this symbolism was localised through the construction of ‘walled pathways’Footnote 63 that materialised the heavenly–earthly transition. Not limited to the Church of the East, even East Syrian Jacobites of the Maphrianate of Tikrit incorporated the bet-šqaqone into their churches, underscoring its Mesopotamian regional consistency. Although textual reference to the bet-šqaqone appears only in the eleventh-century Kitab al-Muršid by Yahya ibn Garir,Footnote 64 its architectural manifestations suggest a much earlier origin and indicate a distinct Mesopotamian liturgical system diverging from northern Syrian models. A representative example is Hira XI Church (Figure 8d), in which 12 arched wall niches along the bet-šqaqone may have once contained statues of the Apostles,Footnote 65 visually enacting the liturgical passage from Earth to Heaven. This symbolic arrangement provides a crucial context for interpreting similar iconographic programmes, such as those found in the Tangchaodun bema.

With the gradual strengthening of the influence of East Syriac Christianity in Central Asia since the sixth to seventh centuries,Footnote 66 these architectural and liturgical models, particularly the eastern-type bema enhanced in southern Mesopotamia, the concept of the bet-šqaqone, and pilgrimage–monastic integration, were transmitted eastwards from the Persian Gulf into Central Asia. These features played a critical role in shaping the principles of the East Syriac church building in regions such as Central Asia and Xinjiang, China.

The eastward transmission of the East Syrian bema tradition: from Mesopotamia to Central Asia (Xinjiang)

Controversial evidence (Urgut site) in Central Asia and the bema-related liturgical system

In post-Sasanian Central Asia, three undisputed East Syriac Christian sites have been identified: two at Ak-Beshim (Figure 9)Footnote 67 and one at Urgut (Figure 10).Footnote 68 This section focuses on the Urgut site and its purported bema structure, examining how Syrian tradition spread to the Christian buildings in Central Asia and potentially impacted the Xinjiang region.

Figure 9. Plan of Ak-Beshim ‘Building VIII’.

Figure 10. Ground plan of Urgut Church.

Excavator A. Savchenko initially proposed that the Urgut ecclesiastical complex features two aisles divided by a central raised platform that was accessible through an aperture in the western wall, possibly linked to a now-lost mud brick or loess stairway (Figure 11).Footnote 69 B. Ashurov, building on this, argued that the ‘low narrow passage’ connecting the bema to the near-square cross-shaped sanctuary is a ‘substantial structure’ associated with the Mesopotamian bema—specifically the bet-šqaqone.Footnote 70

Figure 11. View over the monastic and parish churches, facing east.

However, in 2022, Savchenko revised his interpretation, suggesting that the Urgut site comprises three main parts from the north to the south: the refectory, monastic church, and parish church (Figure 12).Footnote 71 The so-called ‘central raised platform’ appears to function as a division between the latter two building sections. Savchenko also noted niches on the southern wall of the monastic church, which housed oil lamps—indicating that the platform is part of the solid wall rather than an independent bema structure.Footnote 72 More importantly, the small room to the east of the platform, connected by steps to the sanctuary of the monastic church, is probably an attached vestryFootnote 73 that does not form a mirrored structural pair with the previously mentioned platform. Based on this, combined with the layout of Ak-Beshim Building VIII,Footnote 74 the author also agrees that the raised platform is presumably NOT a ‘ritual structure’ such as the bema.

Figure 12. Idealised plan of the monastery building.

In the Urgut ecclesiastical complex, notable features include the narrow passage connecting the nave and the sanctuary, as well as the spatial organisation within the sanctuary (see Figure 13).Footnote 75 The better-preserved monastic church presents a spatial division between the ‘altar at the eastern (front) end’ and the ‘platform at the western (rear) end’. The altar area serves as the core space for the Eucharistic celebration, evidenced by the priest’s seat and symmetrical ledges raised above the floor for the placement of liturgical implements. The platform, with ‘brick pillars probably serving as two lecterns’, suggests a daily function for scripture reading.Footnote 76 This architectural pattern is representative of East Syrian churches in a monastic compound, in which ‘monastic liturgy’ takes place entirely within the sanctuary, as seen in the Kharg monastery church (Figure 14), where its western part functions as an alternative to the bema.Footnote 77 Simultaneously, the parish church to the south is accessible to laity and is connected to the monastic church via a narrow corridor ‘to bring a relic of a saint from the monastic church to the parish church on the yearly feast of Remembrance without leaving the building’.Footnote 78 A similar layout design is found at the southernmost ‘parish church’ (Building A) of the Ak-Beshim VIII site, where the southern aisle also provides an efficient path for pilgrims wishing to attend shrines and altars.Footnote 79

Figure 13. Spatial division and structures in a monastic church and a parish church (top: altar; bottom: corridor space connecting the nave and the sanctuary).

Figure 14. Spatial division of the sanctuary in a Kharg monastic church.

Inferring from the above evidence, it could be presumed that, in ecclesiastical complexes of Central Asia that serve both parish and monastic functions, the use of a bema follows a pattern that is similar to that of East Syriac Christianity in southern Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf. Inscriptions found near the Urgut site indicate that Christians from the heartland of Mesopotamia and Turkic-speaking migrants from the East settled here,Footnote 80 suggesting that the region not only adopted the Syriac–Mesopotamian ‘Martyrs’ Cult’,Footnote 81 but also developed into a regional pilgrimage centre. While Christian communities in Central Asia during the Mongol era included other churches from the Syriac milieu, such as the Syrian Orthodox church and Melkite church,Footnote 82 archaeological evidence manifests that the East Syrian bema tradition and its associated liturgical system remained dominant. Through the network-connecting Samarkand, Ak-Beshim, and even as far as Turfan in Xinjiang, the relative explicit influence of southern Mesopotamia also reached the Tangchaodun bema church during the Gaochang Uyghur period, which will be discussed in detail later.

Tangchaodun bema in the ‘bema development chronology’

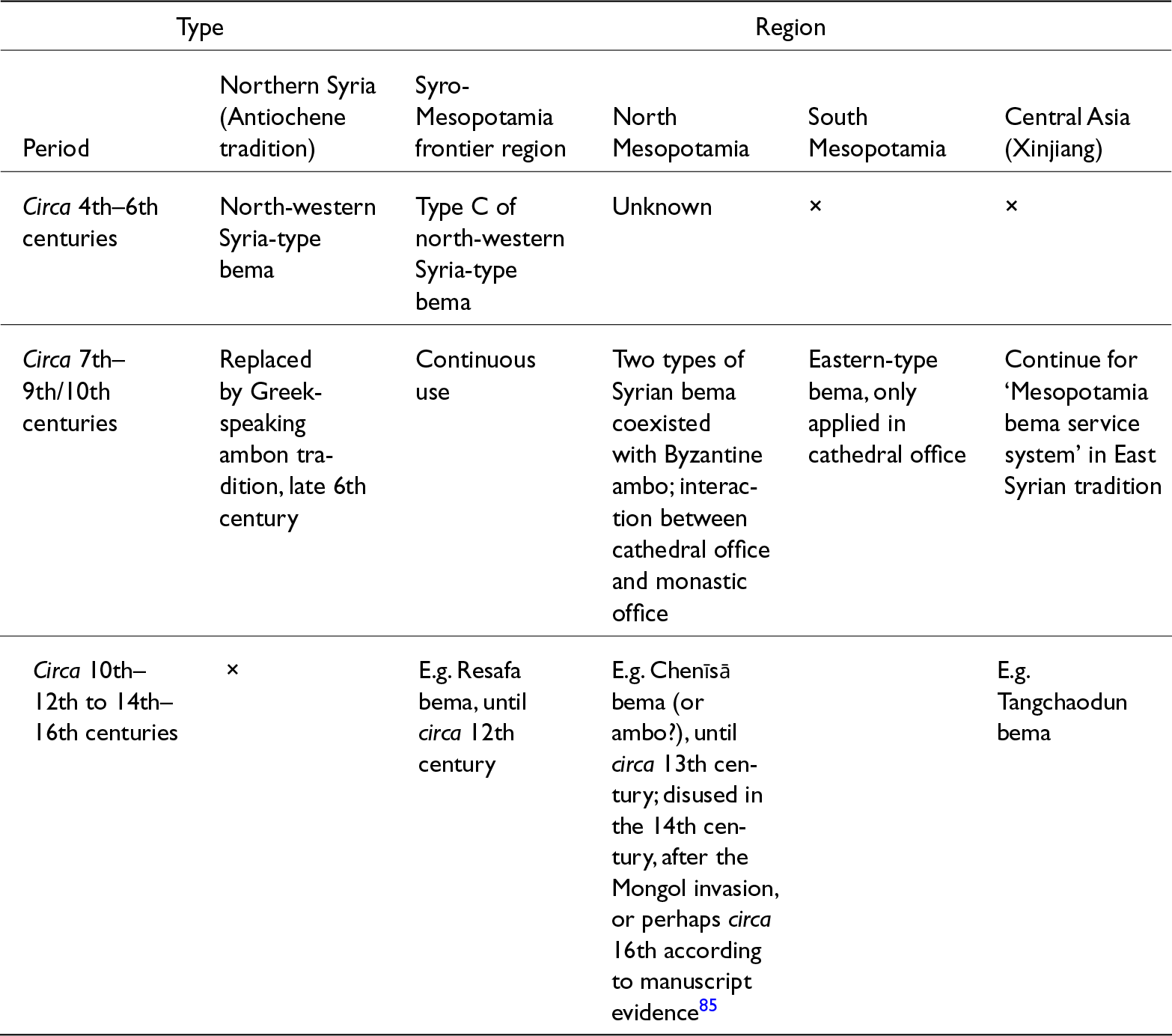

In summary, the origin of the bema can be traced to the centre of the Antioch Diocese. As various Syrian Christian sects and their related liturgies evolved, the bema gradually spread eastwards and developed in various forms, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Chronology of bema development from Syria and Mesopotamia to Central Asia (Xinjiang)

The north-western Syria-type bema of the Antiochene tradition in northern Syria and the eastern-type bema of the East Syrian tradition in southern Mesopotamia are the undisputed representatives of these two liturgical systems. However, within the multicultural context of Syro-Mesopotamia, there is no strict ‘correspondence’ between the shape of the bema, its liturgical function, and the relative Christian denominations. On the other hand, Mesopotamia developed distinct architectural features related to the bema and a dual-purpose functional service system for both monks and laity. This regionality was also integrated into the East Syrian tradition, profoundly influencing the transmission of the bema tradition eastwards.

Considering the temporal and spatial evolution described above, the Tangchaodun bema can be placed within the ‘East Syrian tradition’ milieu of Central Asia (Xinjiang). Its form and church layout design distinguish it from the ‘monastic system’ seen at Urgut and Ak-Beshim. The Tangchaodun bema aligns with the East Syrian theological concept of ‘the bema mirroring the apse’ and can be compared to the bema (church) at Hira. Unlike the isolated monastery located on the outskirts of the capital of Gaochang Uyghur Kingdom in Turfan,Footnote 83 the primary function of Tangchaodun Church was as a parish church serving the laity. Additionally, the church site in Qocho ancient city was excavated and briefly documented by A. von Le Coq; the detailed internal architectural features were not preserved, but its function and attributes should be consistent with those of Tangchaodun Church.Footnote 84 (For the locations of the three sites, see Map 1.) This highlights that, at a time when the Syrian bema tradition in the Mesopotamian heartland of the Church of the East was on the brink of extinction, the distant East preserved this ancient tradition.

Sacred contexts, architectural structures, and liturgical functions of the Tangchaodun bema

Layout of Tangchaodun Church and the bema-centred liturgical process

The Expositio officiorum ecclesiae (Commentary of the Ecclesiastical Services) is the primary work that provides detailed information on the religious symbolism of church architecture and liturgical practices associated with the bema. The book was authored during the early to mid ninth century by a resident of Mesopotamia who was devoted to East Syriac Christianity. Its purpose was to address inquiries regarding the liturgical innovations implemented by East Syriac Catholicos Īshōʿyahb III.Footnote 86 The works of various East Syrian theologians, including Gabriel Qatraya (and also Abraham Bar Lipheh),Footnote 87 from the sixth century onwards also contain material related to this theme.

When observing the layout of Tangchaodun Church from the perspective of the cosmological symbolism of the Antiochene tradition,Footnote 88 the structure of the ‘Heaven (sanctuary)–Paradise (qestroma)–Earth (nave)’ is clearly revealed. Based on the ‘whole world’ conception, as shown in Figure 15, this article attempts to restore the ritual process related to ‘sanctuary–bema’ (see Table 4)Footnote 89 within the church space.

Figure 15. Illustration of ‘whole world’ in Tangchaodun Church.

Table 4. Bema-related liturgy in Tangchaodun Church and corresponding symbolism

The liturgy takes place on the bema, fostering tighter interactions between the clergy and the laity. As E. Loosley notes, bema-related liturgy has a very clear purpose: ‘for those who could not undertake a pilgrimage to Jerusalem the clergy enacted a weekly ceremony that symbolically drew a map of the world for the faithful.’Footnote 90 Referring to Canon XV from the Synod of Mar Isaac held at Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410 CE,Footnote 91 ‘liturgy in the midst of people’ dates back to the beginning of the fifth century, just before the initial eastward spread of East Syriac Christianity; this idea is also preserved in church buildings from Central Asia to Xinjiang. In conjunction with the liturgical ceremony, the bema and its imagery served as powerful media for disseminating the faith and informing believers.

Liturgical furnishing on the platform of the Tangchaodun bema

The central one-third of the Tangchaodun bema platform exhibits a slight concave shape, with a preserved notch located in the middle of the eaves on both the south and north sides of the platform. The layout can thus be divided into three distinct parts: (a) east, (b) centre, and (c) west, each of which will be examined in detail. Considering the role of the bema in the ritual process as described in the written sources, this section analyses the liturgical furnishing structure of the Tangchaodun bema plan in relation to the aforementioned eastern-type bema, which shows a relatively complete structural preservation in comparison with the architectural details of the Resafa bema, which is significant in the transformation of the bema pattern.

Theoretically, the Tangchaodun bema is similar to the Hira bema, based on standard East Syrian tradition (see Figure 16).

Figure 16. Three-part division of the Hira and Tangchaodun bemata.

Part a: The easternmost part contains the ascending steps up to the bema platform and comprises two pulpits: one located in the south-east corner and the other in the north-east corner. The bema of the East Syrian tradition consists of two parts: one for recitation of the Old Testament and the other for the New Testament. The preaching is oriented towards the east, with all parties facing that direction during prayers and Eucharistic liturgy.Footnote 94

Part b: The central area is the heart of the bema and representative of the centre of earthly Jerusalem, where tradition records that the tomb of Adam was found. This area of the bema, which is used to hold the Gospel and the processional cross, symbolises Golgotha.Footnote 95 The Gospel and cross echo the sanctuary symbolising the Resurrection and Ascension of the Lord, reinforcing in another form the ‘mirroring relationship’ between the bema and the sanctuary in East Syrian theology. The archaeological remains of columns in bemata in Syria suggest the possibility of a corresponding ciborium above the bema.Footnote 96 Regarding the Tangchaodun bema, there is no evidence that it was accompanied by a fixed ciborium.

Part c: As the Expositio officiorum ecclesiae notes, the bishop’s throne is located at the western end of the bema, facing east towards the sanctuary. To the left of the bishop’s throne is the seat of the archdeacon.Footnote 97 The Hira and Bazyan bemata show the evident remnants of a cathedra. By inference, the Tangchaodun bema should be similar to those cases.

In addition to the aforementioned significant liturgical furnishings, it is also important to mention the seats for the concelebrating priests. This is a designated area, known as the space for 12 men (symbolising the Apostles) that is connected to the bishop’s throne.Footnote 98 It is associated with the upper room and the Last Supper. Both the East and West Syrian traditions agree concerning this space, on the basis of written sources and archaeological evidence.Footnote 99

Based on the typical north-western Syria-type bema and the case associated with the Church of the East, we can infer that, apart from the bishop and archdeacon positioned at the west end and readers situated in the two pulpits at the east end, the remaining clergy likely sat on the south and north sides of the bema. This is supported by evidence from the Hira bema as well. P. Donceel-Voûte examined the arrangement of bemata in churches in Farfenteen and Dibsi Faraj, which belong to the Antiochene tradition: In Farfenteen, the bema is laid out with a ‘west bema-throne/pulpit + bench seats on the north and south sides’.Footnote 100 In the similar case in Dibsi Faraj, the layout is enhanced with addition of a ciborium in the centre and a small vestibule at the east end (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Seat arrangements of the Faferteen and Hira bemata.

The article will now examine the Tangchaodun bema in more depth. Donceel-Voûte noted of the Dibsi Faraj bema that its seats were approximately one metre in width—greater than the width of other bema seats that include a backrest.Footnote 101 By comparison, the breadth of the eaves on the platform of the Tangchaodun bema is comparable to the width of the bench seats found in the south aisle of a church. These eaves measure approximately 0.3 to 0.4 metres in width and 0.3 to 0.5 metres in height. Nevertheless, there is a substantial difference in the height between the eaves and the bench seats, and there is no evidence of any permanent or supported wooden structures, such as the backrest of a chair. Despite the extensive damage and deterioration over the centuries, the adobe-rammed eaves of the Tangchaodun bema do not have brick borders that the synthronon in the Bazyan bema has. Presumably, the Tangchaodun bema platform only allows the placement of individual, portable wooden seats. With reference to the Syro-Mesopotamia bemata, the seats for the clergy, including the bishop’s throne, were primarily situated in the western part, as the eastern and central areas were already properly organised. Therefore, excluding the bordering section, the Tangchaodun bema measures approximately five to six square metres, providing space for approximately four or five individuals to sit. Based on the way in which the bema-related liturgy is carried out, priests, deacons, and vigilers have the opportunity to alternate their presence on the bema and engage in the ceremony. Through this approach, the available space can be efficiently utilised to convey the significance of the cosmological system to the faithful through the liturgy.

Considering the administrative level of Tangchaodun ancient city,Footnote 102 though we lack sufficient evidence to know for sure, it seems likely that Tangchaodun Church was a parish church, not a cathedral with a bishop, but it is reasonable to assume that the local bishop (perhaps in Qocho?) would have visited Tangchaodun from time to time. As Loosley notes, the West Syriac Ordo quo episcopus (The order for a bishop) highlights the great importance of the bema for the Liturgy of the Word and the instructional elements of the service, particularly when bishops from nearby areas attended.Footnote 103 According to the Expositio officiorum ecclesiae Footnote 104 and assuming that Tangchaodun Church was indeed a parish church and not a cathedral, the liturgy would normally have been presided over by a local priest(s).

Stairs and height of the Tangchaodun bema

The Tangchaodun bema contains a staircase that provides access to the platform, located in the centre of the east side. The staircase is around 0.7 metres wide and consists of five steps, which gives the Tangchaodun bema a height of two metres. This is in contrast to the bemata in Mesopotamia, in which there are typically two or three steps, comparable to the number of stairs leading up to the sanctuary,Footnote 105 which aims to create a symbolic theological system that corresponds to the concepts of the earthly Jerusalem and Paradise–Heaven by making the height of the bema nearly identical to that of the altar in the apse.

Beyond its practical function, the ‘staircase’ of the Tangchaodun bema may carry additional symbolic significance. Unlike typical East Syrian bema churches in Mesopotamia, Tangchaodun Church lacks any trace of an independent bet-šqaqone—that is, a ‘wall-flanked passage’. In East Syrian theology, the bet-šqaqone is an abstract concept often associated with Jacob’s ladder—an ‘elevated’ motif that may parallel the symbolic role of the staircase.Footnote 106 Thus, the staircase not only serves the liturgical function of the Tangchaodun bema but also subtly contains the invisible conception of a ‘bridge connecting Heaven and Earth’ and distances it from the distinct architectural identity of Mesopotamian churches, adapting it to the Xinjiang region.

Following the Expositio officiorum ecclesiae, Fiey highlighted the fact that, apart from the main staircase, the construction of the bema may have included two other sets of steps for those who chant the zummārā (a psalm or canticle between the epistle and the Gospel). This was done to prevent them from using the same stairway as those who read the epistle.Footnote 107 The Resafa bema is an exception to this rule: there are stairs located on the south and north sides near the western synthronon. It is possible that this is an ancient tradition that was maintained in Mesopotamia. The Tangchaodun bema does not have these extra steps, and clergy participating in bema-related liturgy would use the primary stairway located on the east side of the bema; no further steps were required, possibly due to the ecclesiastical rank of Tangchaodun Church.

There is also a difference in the height between Tangchaodun and Syro-Mesopotamian bemata. Tchalenko stated that the typical height of bemata in Limestone Massif in north-eastern Syria is approximately 0.5 metres.Footnote 108 The height of the bench, including its backrest, measures around 1.5 metres. The same can be observed about the bemata associated with the Church of the East. Based on the photographs in the excavation report of the Bazyan site, the height of the bema is no more than 0.4 to 0.5 metres—about knee-level for an average adult.Footnote 109 There is less evidence available regarding the bemata at Hira. In contrast, the Tangchaodun bema has a platform height that is much greater than those of the typical Syrian or Mesopotamian bemata. The Byzantine ambo’s influence is evident in the bema’s distinctive structure, which features a central arched doorway connecting north and south; see the discussion in the following part.

The probable association of the Tangchaodun bema with the ambo and cultural influence from the West

This article has analysed the regional development chronology and related liturgical pattern of the Tangchaodun bema, demonstrating its significant East Syrian traditional features. Most importantly, its core function still aligns with Chaldean-rite Christianity norms. However, aside from this, by examining the development and spread of the ambo and its associated religious concepts, and comparing the structural features that are similar to the ambo in the Tangchaodun bema, this article offers valuable insights into the study of East Syriac Christianity during the Gaochang Uyghur period.

In the sixth to seventh centuries, in the province of Syria Prima, where Greek-speaking tradition and Syrian tradition overlapped, the Syrian bema gradually evolved into the Byzantine ambo.Footnote 110 In the Syro-Mesopotamian region, the interaction between Greek-speaking and Syriac-speaking traditions became more frequent. For instance, the Sogitha on the Church at Edessa (sixth century) defines the bema as being more similar to the Greek ambo. It describes the bema (ambo) as based on the model of the Upper Room at Zion, supported by 11 columns, symbolising the ‘hidden eleven apostles’.Footnote 111 Although archaeological evidence may not fully support this ‘idealised model’,Footnote 112 the architectural pattern of a ‘circular platform supported by several columns’ had widespread influence in the Syro-Mesopotamian region.Footnote 113 In fact, even in the very heartland of Byzantine tradition, the ‘religious conceptual model’ of the ambo closely resembles this form. For example, in On the Divine Liturgy by St. Germanus of Constantinople (eighth century), the ambo is defined as a hill placed on a flat and level area.Footnote 114

However, while such ambos have the key structural feature of a hollow interior, the Tangchaodun bema’s feature of an arched doorway connecting the north side to the south side remains distinct. Therefore, this feature should be examined within the broader context of the ambo development system. J. Davies analysed ambo remains in the Byzantine empire’s core region (Asia Minor-Greece), outlining three developmental stages for the ambo:Footnote 115 generally speaking, the standard Byzantine ambo began in the fifth century as a ‘monolithic Ambo with a single flight of steps’, evolving into a ‘semicircular structure with two short steps leading up from the same side to a height-increasing platform’ in around the sixth century. Notably, the third stage, during or after the sixth century, was characterised by the ‘high platform’ and ‘hollow under the ambo-platform’, with two flights of stairs on both the east and west sides.Footnote 116 The high-platform ambo became the most common ambo form along the eastern Mediterranean coast after the sixth century and even continued through the middle–late Byzantine period.Footnote 117

How, then, should we interpret the unusual ‘Byzantine architectural feature’ in the Tangchaodun bema from the perspective of religious and cultural background and transmission pathways?

From the perspective of the Christian sacred liturgical setting, in the sixth to seventh centuries, while the East Syrian tradition did not explicitly adopt the Byzantine ambo form in Syro-Mesopotamia and beyond, the region had clearly been influenced by the ‘ambo–solea’ feature. Therefore, it can be inferred that the ambo and its religious symbolism—‘(The herald) ascending the mountain (Ambo) to announce the good news of Christ’s Resurrection’Footnote 118—would have been known to the followers of the Church of the East, even probably as part of the eastern-type bema’s transmission. At least they would not have explicitly rejected its associated religious meanings. From the seventh to eighth centuries onwards, after the ‘unified Islamization’ of the Syro-Mesopotamian to Syria-Anatolia region, elements of Syrian and Byzantine Christian architecture began to blend, and this influence spread eastwards once again to Xinjiang.

Other ‘foreign elements’ in the Tangchaodun bema and its ecclesiastical complex can also serve as evidence of this process. For example, the inscription on the upper part of the eastern side of the Tangchaodun bema is a mirror image (Figure 18)—that is, both sides are the same word, reading ‘rk’wn (Alaph, Resh, Kaph, Alaph, Ayin, Waw, Nun), transliterated as ärkä‘ün, which is the Uyghur word meaning ‘Christ’,Footnote 119 in which the ‘Alaph’ is written in the West Syrian Serto script. This inscription shows the blending of eastern Estrangela and western Serto features.Footnote 120 The ‘mirror inscription’ form may have developed as a decorative calligraphic style in Syriac and Arabic during the Abbasid period or later.Footnote 121 Additionally, glazed pottery (a pot or vase) found at Tangchaodun Church features Arabic script in repetitive and symmetrical forms (Figure 19),Footnote 122 reflecting the influence of the Western world that prevailed in the Gaochang Uyghur Kingdom.

Figure 18. East side of the Tangchaodun bema, with inscriptions and murals.

Figure 19. Glazed pottery with inscription unearthed in Tangchaodun Church site.

From a broader perspective, the cultural context of Tangchaodun also includes the discovery of a Romanesque bath site on the eastern side of Tangchaodun Church,Footnote 123 which further serves as evidence of Roman–Byzantine architectural and cultural influences. C. Ge suggests that the Tangchaodun city, since its establishment during the Tang Dynasty, likely functioned as a post-station settlement for merchants and pilgrims, possibly part of a post-station network along the Silk Road.Footnote 124 Although no parallel bema/ambo church sites have been found in Central Asia and Xinjiang, the earlier discovery of the Urgut ecclesiastical complex proves the influence of Christian traditions from West Asia, suggesting that the Tangchaodun bema was probably part of this systematised network.

In conclusion, the basic attribute of the Tangchaodun bema is indisputably the eastern-type bema belonging to the Church of the East. However, the appearance of a multicultural fusion ambo-like structure in far-off Xinjiang, distant from the heartland of East Syriac Christianity, does require further archaeological discoveries to verify its regional development chronology. Nonetheless, East Syrian theology had already undergone a process of borrowing and theoretical fusion with the Greek-speaking tradition by the fifth to sixth centuries.Footnote 125 Thus, it is reasonable to infer that the incorporation of ambo-like architectural features into bema building during the Gaochang Uyghur Kingdom manifests a subtle reflection of the historical trend.

A preliminary interpretation of the iconography of the Tangchaodun bema

The excavation team at Tangchaodun have found traces of wall paintings on both the east and west sides of the bema. The paintings on the north part of the Tangchaodun bema’s east wall depict a figure on a red horse or donkey. Furthermore, in the centre of the west side of bema is a niche, about one metre wide and 0.3 metres deep, flanked by two symmetrical decorative columns on either side, all of which is built on top of a rectangular earthen platform (Figure 20). An octagonal pedestal can be seen at the bottom of the centre of the niche, approximately 0.45 metres in diameter. There are traces of white plaster and mural paintings on the wall surface, but these are covered by plaster and damaged so seriously that it is impossible to recognise the specific original content of the mural paintings.Footnote 126

Figure 20. The western wall of the Tangchaodun bema (looking eastwards).

Drawing on bema-related liturgy, its symbolic significance, and the religious traditions rooted in its Syro-Mesopotamian origins and expansion, as well as the development of the Church of the East in the Gaochang Uyghur Kingdom, this section analyses archaeological and textual evidence to demonstrate that the Tangchaodun bema comprises two interrelated iconography–narrative systems. These systems complement each other, deepening the bema’s religious significance and playing a vital role in shaping the sacred space of Tangchaodun Church.

Iconography system I: substantial depiction of Holy Week

The first iconography system of the Tangchaodun bema likely represents Holy Week. Clues to this system appear on the eastern and western walls of the bema.

Drawing on iconographic parallels from Qocho ChurchFootnote 127 and the Xipang Monastery site (Figure 21), which were built and developed simultaneously, the mural on the east wall—depicting Christ wearing a cross-adorned crown and holding a cross sceptre (Figure 22)—suggests a motif of the ‘Entry of Jesus into Jerusalem’. The inscription ärkä‘ün (see Figure 18) at the top of the eastern side of the bema corresponds to the black-ink inscription of the Master Yelikewen (Figure 23) on the south side of the north-eastern pillar, reinforcing Christ’s identity and linking the bema structure to his life. This scene also parallels the symbolic significance of the liturgical step, where the bishop and clergy exit the sanctuary and ascend the bema. Just as Christ’s earthly journey was accompanied by the Twelve Apostles, the niche statue carved in the bet-šqaqone of Hira Church embodies this concept.Footnote 128 Although the typical Mesopotamia-style bet-šqaqone is absent in Tangchaodun Church, it is reasonable to infer that, following standard East Syrian tradition, the east wall of the bema—directly facing the sanctuary—depicts the beginning of Holy Week, symbolising Christ’s earthly experiences.

Figure 21. Head of Christ wearing a crown adorned with a cross.

Figure 22. Line drawing of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, on the east side of the Tangchaodun bema.

Figure 23. Inscription of Master Yelikewen in Uyghur script.

The imagery on the Tangchaodun bema’s western wall follows a ‘sculpture-in-central-niche and paintings-on-both-sides’ arrangement. Based on the Syrian tradition and Eastern Christian art, this wall likely draws a Traditio Legis-like motif, depicting Peter and Paul as representatives of the Apostles proclaiming Christ’s law and the Gospel to the nations from Jerusalem.Footnote 129 This theme aligns with the symbolic meaning of the bema as earthly Jerusalem.

A common element in Traditio Legis scenes is a row of lambs/sheep beneath the Apostles flanking Christ, sometimes with Christ accompanied by two lambs. These elements likely symbolise believers from all nations.Footnote 130 Similar symbolic representations of the Apostles and believers appear in Syrian bema sites. For example, the bema mosaic at Uqayribat features a palm tree, representing the Tree of Life, alongside three sets of heraldic lambs (Figure 24).Footnote 131 Given that the fruit of life was promised by the Tree of Life,Footnote 132 this mosaic likely allegorises the apostolic adoration of Christ. Likewise, the two lambs depicted in the Rayan bema mosaic (Figure 25) probably hold comparable religious significance.Footnote 133

Figure 24. Bema mosaic at Uqayribat: palm tree and heraldic lambs.

Figure 25. Bema mosaic at Rayan: vase and heraldic lambs.

Another significant case of archaeological and iconographic evidence in the Syriac tradition is the Dedication (folio 14r) from the miniatures of the Rabbula Gospels (586 CE),Footnote 134 likely produced in the region between Antioch and Apamea; this manuscript provides vital evidence from which to infer that the prototype of the Traditio Legis originated in the Syriac region.Footnote 135 Beyond the standard connotations of the Traditio Legis in Syrian bemata iconography, what is more noteworthy is its localised adaptations.

The Dedication depicted an enthroned Christ with two monks in the monastery at Beth Zagba, offering their dedications to Him, under the sponsorship of two indigenous patron saints.Footnote 136 Early Christian imagery was rarely a mere illustration of biblical texts, but instead carried symbolic and allegorical significance. Thus, while the Traditio Legis serves as a compositional reference, the murals flanking the Christ sculpture in the Tangchaodun bema may not necessarily depict Peter and Paul; the alternative could feature saints venerated in the Church of the East or even monks who lived at Tangchaodun, aligning with the cult of saints, which is further explored in ‘Iconography system II’ of the Tangchaodun bema.

Beyond explicit iconographic evidence, the Hetoimasia motifFootnote 137 in early Christian art—particularly the representations of Golgotha and the altar on the bema—serves as an indispensable part in constructing Holy Week. The Hetoimasia—the Throne of Christ’s Sacrifice—symbolises the Holy Liturgies that sanctify believers and prepare them for the Last Judgement. Structurally, the bema itself can be seen as an ‘empty throne’, representing Christ’s presence through the Gospel and the cross, as confirmed by bema screens and mosaic inscriptions found in Syria.Footnote 138 At the practical level of a real building context, the ‘empty throne’ corresponds to the episcopal throne, which, in the absence of the bishop, serves as a perpetual reminder of his authority.Footnote 139 Within the architectural framework of the bema, all imagery ultimately reinforces the supreme authority of Christ and theoretically, by extension, his representative, the bishop.

Above all, considering the theological symbolism in Syriac Christianity and the doctrinal principles of the Church of the EastFootnote 140—rooted in the School of Nisibis and favouring the theologia prima of liturgy over academic theological reflectionFootnote 141—this article seeks to reconstruct the iconographic and liturgical furnishing system of the Tangchaodun bema and to explain how it visually elaborates Holy Week (Table 5).

Table 5. Substantial depiction of Holy Week in the Tangchaodun bema

Iconography system II: tradition of saints’ veneration

The second iconography system of the Tangchaodun bema consists of images of the south and north sides. This structure exhibits a symmetrical design, featuring a total of eight enclosed frames that are recessed inwardly by approximately two centimetresFootnote 143 (see Figure 26). Additionally, some of these frames still bear inscriptions in ink along their edges. The prevalence of Buddhist grotto art in the Gaochang Uyghur KingdomFootnote 144 suggests that such niches typically housed seated or standing figures. Given their shallow depth—unlike the main sculpture on the west wall—the images within were likely flat or rendered in low relief. In Buddhist art, figures with inscriptions in frames often represent donors.Footnote 145 By analogy, in the localised Christian context, they were presumably saints or martyrs subordinate to the Lord God.

Figure 26. The southern wall of the Tangchaodun bema (four niches) (looking northwards).

As noted earlier, the north-western Syria-type bema in northern Syria (Antioch) was closely associated with the tradition of saint/martyr worship from the fourth to fifth centuries. Archaeological evidence indicates that this tradition persisted and even intensified in the eastern-type bema of Syro-Mesopotamia from the sixth century onwards. The canon of the Church of the East explicitly requires bishops to preach on Sundays, feast days, and saint commemorations as well,Footnote 146 underscoring the significance of saint veneration in the East Syrian tradition.

As East Syriac Christianity spread from Sasanian Persia to Central Asia, this tradition remained strong, at least through the tenth to thirteenth centuries. For inferences about the identity and attributes of the characters, reference is made to Syriac Christian literature unearthed in Turfan from the ninth to tenth centuries and onwards: Christian figures revered by Christians in the Gaochang Uyghur Kingdom, including the saints George, Sergius, Bacchus, Cyriacus, and Julitta, were adored not only in Central Asia but also in Western Asia and Mesopotamia, and in Greek and Latin Christendom. In addition to these widely recognised figures, Central Asia has its own local saints who played a significant role in introducing Christianity to the region, namely Mar Barshabba, the Persian queen Mart Shir, and Zarvandokht.Footnote 147 The northern and southern sides of the Tangchaodun bema may have been adorned with depictions of some of these saints. It is plausible that the north and south sides of the Tangchaodun bema were adorned with depictions of some of these saints. In a religiously pluralistic Gaochang Uyghur Kingdom, in which Christianity coexisted with Buddhism and Manichaeism, images of saints and martyrs visually reinforced the Christian spirit of dedication during daily liturgical practices.

Regarding saint veneration within the liturgical context of the bema, Catholicos Patriarch Mar Awa III has analysed Syriac manuscript MIK III 45 from Turfan, containing 61 folios from the Ḥūḏrā of the Church of the East, from which he concluded that the week-long festive observance of the commemoration of the saints resembles the liturgy of the hours of the Lenten season. As Holy Week is an essential part of the Lenten season, this connection further underscores the religious significance of the bema.

In sum, the Tangchaodun bema embodies dual religious systems: (1) Holy Week (Great Lent), which prepares the faithful not only to commemorate but also to partake in the Passion and Resurrection of Christ; and (2) the Cult of Saints and Martyrs, represented by the Ceremony of the Saints. These two dimensions, mutually reinforcing and intertwined, condense multiple liturgical and theological functions into the architectural space of the bema.

Conclusion

The Tangchaodun bema stands as a compelling testament to the eastward transmission, preservation, and transformation of the East Syrian Christian liturgical tradition. Rooted in the Antiochene ecclesiastical framework and structurally aligned with the eastern-type bema, it reflects the core spatial and theological principles of the Church of the East. Its architectural form and symbolic organisation bear strong affinities with liturgical developments in Mesopotamia, especially the heartland of East Syriac Christianity, suggesting deep regional influences along the eastward movement of Syriac Christianity. The Tangchaodun bema, closely aligned with ecclesiastical complexes in Central Asia, represents a regional manifestation of the same theoretical model that structured the Church of the East’s liturgical architecture throughout its eastern expansion. While some design elements evoke distant affinities with Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture, these are better understood as formal echoes shaped by long-range cultural contact rather than as direct architectural borrowings.

Through its spatial organisation and symbolic features, the Tangchaodun bema exemplifies the cosmological logic embedded in East Syrian theology. In its structural configuration, it coheres with both the architectural hierarchy of church building and functional requirements of East Syrian liturgical practice. Meanwhile, traces of iconography and bilingual inscriptions point to a visual and textual synthesis shaped by intercultural currents, revealing how the Gaochang Uyghur context reinterpreted established Christian forms within a pluralistic religious landscape.

Far from being a passive recipient of Christian forms, the Gaochang Uyghur Kingdom, and sites such as Tangchaodun in particular, actively reinterpreted and localised the tradition of the bema. Its synthesis of the Syriac liturgical structure with regional material culture resulted in a sacred architectural language that was at once orthodox in theology and adaptive in form. In this sense, the Tangchaodun bema does not merely preserve a fading tradition from the Mesopotamian heartland but reanimates it at the cultural frontier, affirming the vitality of Christian expression in the medieval East.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my immense gratitude to Dietmar Winkler and Li Tang for allowing me to present an initial version of this article at the 7th Salzburg International Conference: Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia in 2023, Samarkand. The article also owes a great debt to Erica Hunter and Mark Dickens, as well as two anonymous reviewers, whose suggestions and comments helped clarify the structure and strengthen the argument. In addition, I sincerely thank Valerii Kolchenko for providing me with important archaeological materials on Christian remains in Central Asia, which have supported part of the key arguments in this article.

Conflicts of interest

None.