Introduction

An independent judiciary places an important check on the power of leaders, a fact which makes pinnacle courts a high-profile enemy of incumbents who would prefer to enact their agenda without the encumbrance of judicial review (Vanberg Reference Vanberg2000). As recent episodes of democratic backsliding show, constitutional courts around the world are targets of incumbent attacks which undermine high court power and institutional legitimacy (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018; Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020). Although it has long been assumed that public support for judicial institutions might safeguard courts from incumbent interference, recent research casts doubt on the public’s willingness and ability to come to the rescue of a court. Whereas public support is essential to the vitality of democracy and democratic institutions – and acutely so for courts – understanding how citizens in hostile versus hospitable environments form their preferences for judicial independence is essential. Such insights may inform our comprehension of the broader processes of democratic backsliding and autocratic consolidation, and identify scope conditions under which the public’s support may work to safeguard judicial institutions from incumbent interference.

Public awareness is a longstanding correlate of public support for courts–indeed it was famously claimed that “to know courts is to love them” (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998, 345). Despite the centrality of awareness as an explanation for the public’s wellspring of institutional support, we have only a nascent understanding of how awareness fosters good (or bad) public evaluations of judicial institutions, and how both individual and contextual factors combine to inform the public’s attitudes regarding courts and judicial power.

The purpose of this research is to understand how awareness, national context, and the public’s evaluation of executive influence informs the public’s demand for judicial independence. We examine a question that is central to our understanding of public support for judicial institutions: Under what conditions does being more aware of a court foster a demand for independent judicial review? Previous theoretical accounts would suggest that awareness brings with it increased exposure to judicial symbolism that cultivates public support for judicial power and independence (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009b; Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2017), especially in contexts where incumbents’ meddling is minimal, adherence to judicial decisions is widespread, courts are powerful, and interbranch relations are generally hospitable (Aydın-Çakır and Şekercioğlu Reference Aydin-Çakir and Şekercioğlu2016; Garoupa and Magalhães Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021). To summarize the previous research we aim to expand, we have a good theoretical understanding of how awareness might function to foster support for judicial power, but really only under the best of circumstances.

We bring some additional evidence to bear on this important question, to tease out what it is that increased awareness brings to foster support, not only in hospitable environments where institutional assaults on courts are rare or do not occur, but also in hostile environments where executives actively interfere with high courts to erode judicial independence. Our argument posits that the association between awareness and attitudes about judicial independence is shaped by incumbents’ interference with courts, as well as citizens’ perception of said interbranch dynamics. In particular, we argue that recalcitrant elite behavior influences what highly attentive citizens know and learn about judicial institutions, and although perceptions of executive meddling might undermine the public’s trust, it also corresponds to preferences for limiting executive influence within high courts, which we conceptualize as greater demand for judicial independence.Footnote 1

We draw on nationally representative surveys fielded in two hospitable contexts, the US and Germany, and two hostile contexts, Poland and Hungary. Our surveys contained questions regarding the public’s awareness and knowledge of their national high courts that have not been asked on comparative surveys in many decades, despite the theoretical centrality we outline below. Our surveys also include original questions which probed the public’s perception of executive influence on the national constitutional court, as well as their demand for judicial independence in these same institutions – questions that go beyond the standard battery of survey items regarding national courts. This more extensive set of questions that gauge public support for courts, combined with the paired comparison research design of cases selected for their variance on national context (hostile vs. hospitable), gives us an opportune moment to revitalize a well ensconced theoretical inquiry that has long been hamstrung due to the lack of empirical measures.

To preview the results, we first document a robust positive association between awareness and perceptions of executive influence in courts in hostile (but not hospitable) environments, suggesting that awareness in these contexts reflects exposure to incumbents’ court-curbing attempts. Moreover, we find a positive correlation between awareness and demand for judicial independence only in hospitable environments, but we also show that this association depends on citizens’ perceptions of executive influence. These findings are consistent with the work of previous comparative research (Staton Reference Staton2010; Aydın-Çakır and Şekercioğlu Reference Aydin-Çakir and Şekercioğlu2016; Garoupa and Magalhães Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021), indicating that awareness’ positive influence on public support for judicial power is conditional on other individual and contextual factors. As such, of the famous adage about knowing and loving courts, we would add that it largely depends both on individuals’ knowledge, as well as on the court (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Garoupa and Magalhães Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021).

This article is organized as follows. In the next section, we discuss the literature on public support for the judiciary, especially when faced with executive interference. Next, we describe our four cases – the US, Germany, Poland, and Hungary – which, while all democracies, differ in whether the executive has made institutional changes to curb the high court. We then develop our argument and derive several hypotheses which we will test. From here, we provide descriptive evidence to demonstrate that context matters when determining evaluations of executive interference with the court.Footnote 2 Finally, we discuss our empirical strategy, and present the results from our analysis. We end with a discussion of the implications of our findings for judicial independence, and the conditions under which the public might be a bulwark against undue executive encroachment.

Awareness, Executive Interference, and Public Support for the Judiciary

Widespread public respect for courts and judicial institutions, under the best of circumstances, can substitute for courts as both a shield and sword.Footnote 3 Public support may provide a modicum of protection – safeguarding judicial institutions against attacks from incumbents or other branches who may face a penalty of loss of public support for attacking judicial independence (Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2023b). Public support is also theorized as a critical precondition to enforcement of judicial decisions – ensuring faithful implementation of court decisions and judicial directives (Vanberg Reference Vanberg2001, Reference Vanberg2005; Staton Reference Staton2006, Reference Staton2010; Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel2016).

Our understanding of public backing of judicial institutions has long been shaped by Easton’s distinction of specific and diffuse support (1965, 1975), which has generated a long and vibrant stream of research into the foundations of public support for judicial institutions (Caldeira and Gibson Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992; Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013, Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Christenson and Glick Reference Christenson and Glick2015; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2023b). Per Easton’s typology, specific support is associated with citizens’ evaluation of institutional policy outputs and performance, while diffuse support (also known as institutional legitimacy) refers to individuals’ commitment to the institution, independent of its outputs, and is characterized by a general intolerance of structural changes to the institution or its powers.Footnote 4

Much of what we know about these two sorts of supports is grounded in analyses of a well-vetted battery of survey items on nationally representative samples, such that these two dimensions of public support can be empirically differentiated in ways that are comparable both across contexts and over time (Caldeira and Gibson Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992; Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira1995, Reference Gibson and Caldeira1996; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003; Gibson Reference Gibson2007; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2015, Reference Gibson and Nelson2016, Reference Gibson and Nelson2017; Nelson and Tucker Reference Nelson and Tucker2021; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2023a, Reference Driscoll and Nelson2023b; Nelson and Driscoll Reference Nelson and Driscoll2023; Driscoll, Krehbiel, and Nelson Reference Driscoll, Krehbiel and Nelson2025). Since a fundamental condition for public support to serve as a protective mechanism for judicial institutions is that the citizenry is aware of courts and their decisions (Vanberg Reference Vanberg2001; Staton Reference Staton2006; Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel2016), existing research has long studied the relationship between public awareness of judicial institutions and citizens’ support for the court.

Early scholarly entrées into the connection between awareness and institutional support was the scrutiny of Dahl’s (Reference Dahl1957) famous hypothesis concerning courts’ ability to legitimize controversial policy (Murphy and Tanenhaus Reference Murphy and Tanenhaus1968; Adamany and Grossman Reference Adamany and Grossman1983; Driscoll, Krehbiel, and Nelson Reference Driscoll, Krehbiel and Nelson2025). Seeking to understand the attitudinal foundations of compliance with the rule of law (Caldeira and Gibson Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992), US-based survey research documented that increased knowledge of political affairs and awareness of the court are associated with increased support therefore (Kessel Reference Kessel1966; Adamany and Grossman Reference Adamany and Grossman1983).Footnote 5 Scholars generally understood this correlation to reflect a more thorough childhood socialization around political affairs and institutions, leading the politically sophisticated to prioritize order versus conflict, be accepting of the status quo of the political regime, and to value political institutions as an end unto themselves (Easton and Dennis Reference Easton and Dennis1969; Caldeira Reference Caldeira1977).

A prominent model of this relationship is Positivity Bias Theory by Gibson and colleagues, who have famously argued that “to know courts is to love them” (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998, 345). According to this view, as citizens know more about courts, they are also exposed to the “legitimizing” symbols of the judiciary. Such exposure leads citizens to develop a strong loyalty to judicial institutions and a tendency to subscribe to the “myth of legality” (Scheb II and Lyons Reference Scheb and Lyons2000). These preexisting, positive attitudes are activated each time courts become salient to individuals, reinforcing both the idea that judicial institutions are “non-political” and that court decisions were reached by following impartial or neutral procedures (see Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009a; Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014). Empirically, cross-sectional studies report a strong positive association between awareness of courts and support for these institutions (Caldeira and Gibson Reference Caldeira and Gibson1995; Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Benesh Reference Benesh2006).Footnote 6 According to this literature on Positivity Bias, awareness influences public attitudes about courts through a socialization process by which greater exposure to judicial institutions and their outputs leads citizens to hold courts in high public regard.

Yet comparative scholars have more recently demonstrated that this (positive) relationship between public awareness of judicial institutions and support for courts is highly contingent on contextual factors. This literature has shown that, under certain institutional conditions, increasing public attention to courts can in fact become detrimental to public support for the judiciary. For example, Aydın-Çakır and Şekercioğlu (Reference Aydin-Çakir and Şekercioğlu2016) argue that highly aware citizens in developing democracies are less supportive of courts, as these individuals are able to recognize that the judicial system does not function well (see also Salzman and Ramsey Reference Salzman and Ramsey2013). Their analysis of forty-nine countries reports that individual-level measures of political awareness (education, political participation, and political interest) are positively correlated with public confidence in the judiciary, but only among advanced democracies. As democracy levels decrease to those of developing or non-democracies, awareness has a negative effect on respondents’ support for judicial institutions (Staton Reference Staton2010, Ch. 6). Garoupa and Magalhães (Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021) tell a similar story. The authors suggest that the institutional properties of the judicial branch moderate the effect of awareness on support for judicial institutions: awareness is positively correlated with trust in the judiciary only where judicial institutions are both independent and accountable; where courts lack such institutional attributes, awareness should have a negative effect on trust in the judiciary.

Together, this research suggests that the particular features of the institutional environment in which courts exist will shape the effect of awareness on public evaluations of judicial institutions. As Staton (Reference Staton2010, 153) puts it, “The relationship between awareness and judicial legitimacy is likely conditioned by the kind of information to which people are exposed as they become familiar with their high courts.” According to this view, then, being more aware of judicial institutions provides citizens with information about the performance or functioning of courts, and where these institutions do not perform as expected, greater awareness leads to more negative evaluation of courts.

Much of this research has been hamstrung by lack of consistent measurement across cases and studies, making it difficult to know how to interpret what we see. The well-vetted battery of questions that can differentiate between diffuse and specific support are rarely available on cross-national surveys (Driscoll and Gandur Reference Driscoll and Gandur2023); accordingly, comparativists use available metrics, leaning mostly on survey questions of institutional “trust” or “confidence” which appear on international surveys.Footnote 7 Cross-national surveys most commonly query respondents about their trust or confidence in judicial institutions, but the focal institution in question varies broadly across applications and over time, from the “legal system” (European Values Survey 1981, 1990, 1999, 2008; Eurobarometer 2008), to “courts” (European Social Survey 2010), the “judiciary” (Latinobarómetro 1995–1998, 2000–2011, 2013, 2015–2023), or the “Supreme Court”, “Constitutional Tribunal” and “Justice System” (Americas Barometer 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2021, 2023).Footnote 8 Although Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003) have shown that these items most closely correspond with specific, rather than diffuse support, the dearth of measures that resemble the institutional commitment concept implies that many researchers must work with what they have. Accordingly, these low levels of trust are often interpreted to mean that courts are fundamentally lacking in legitimacy, which implies the public might be either unable or unwilling to punish incumbents who undermine or ignore high courts, or even that the public’s distaste for courts is at the root, serving as a primary cause of interbranch conflict observed throughout the world (Helmke Reference Helmke2010a, Reference Helmke2010b; Clark Reference Clark2011).

This lacunae between theoretical concepts and empirical measures is important for our interpretation of that data we observe, and what lessons we derive to inform our theoretical models. If on the one hand, low trust is indicative of a fundamental lack of institutional legitimacy and a willingness to tolerate fundamental changes to (or even doing away with!) a court, then this low trust from political sophisticates might be a driving cause for the hostile environment, rather than the result thereof. Indeed, prominent models of interbranch conflict suggest that it is diminished public support for the courts that drives incumbent attacks on courts in the first place (Clark Reference Clark2009; Helmke Reference Helmke2010b). If instead we interpret the lack of trust amongst more informed members of the public as a reflection of the institutional environment itself, then this inverse correlation between awareness and trust does not reflect a willingness to disregard the court out of hand, but instead a dissatisfaction with the status quo, and a desire to see changes not in the fundamental institutions, but in the institutional environment in which courts exist.

We bring a bit of data to bear on this question, relying on original surveys fielded in the US, Germany, Poland, and Hungary in June and July of 2021.Footnote 9 These four countries were selected into our study due to their divergent environments as it relates to interbranch politics: in two cases (the US and Germany) the high courts are independent, powerful, and broadly revered as such by the public. Coincidentally, they are insulated from incumbent interference and institutional reforms; they are what we characterize as “hospitable” environments. In Poland and Hungary, although the constitutional tribunals enjoy a full portfolio of institutional powers and formal independence, they have in recent years been the subject of high profile government hostility and capture; they are generally viewed as being co-opted by the ruling coalition, and are not held in high regard.

Importantly, our surveys included several items that move beyond standard measures in courts and public opinion research to interrogate these dynamics more closely. These original surveys are some of the most comprehensive comparative studies of public support for the rule of law and of judicial institutions to date (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Driscoll, Krehbiel, and Nelson Reference Driscoll, Krehbiel and Nelson2020; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2021), which contain information on the public’s support for the incumbent governments, evaluation of and support for institutions, and support for democracy and the rule of law.Footnote 10 In addition to the well-vetted metrics of specific and diffuse support for pinnacle courts with constitutional review (Caldeira and Gibson Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003), our surveys included an original question that tapped into the evaluations of executive influence within high court decision-making.

Using these novel data to address questions on awareness of judicial institutions is all the more important given the changes in the media environment since pioneering cross-national studies in the 1990s. Citizens have a richer media environment than they did decades ago, and recent research in the US shows that such environment matters for public attitude formation about high courts (Johnston and Bartels Reference Johnston and Bartels2010; Zilis Reference Zilis2015; Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018; King and Schoenherr Reference King and Schoenherr2024). Although a full interrogation of the media environment across contexts is beyond the scope of this study, the global shifts in media consumption underscore the importance of (re)examining this critical link between public awareness and support for courts, in both hostile and hospitable contexts (cf. Driscoll, Aydın-Çakır, and Schorpp Reference Driscoll, Aydın-Çakır and Schorpp2024).

Hostile vs. Hospitable: Putting Courts in Context

Citizens throughout the world reside in countries where the relationship between the executive and high court is either hostile or hospitable. While there are many ways to conceptualize hostility toward the judiciary (or the lack thereof) (e.g., “narrow vs. broad” court curbing (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020), verbal attacks to intimidate the judiciary (Bright Reference Bright1997; Clark Reference Clark2009), or “formal vs. informal” (Aydın-Çakır Reference Aydin-Çakir2023)), we conceptualize hostile environments as countries where the executive has made institutional changes to the high court which reduce its judicial independence. In contrast, hospitable environments include countries where few or no institutional reforms have been made.Footnote 11 Insofar as the institutional environment has been shown to be impactful for public opinion and preference formation relating to courts (Aydın-Çakır and Şekercioğlu Reference Aydin-Çakir and Şekercioğlu2016; Garoupa and Magalhães Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021; Driscoll, Aydın-Çakır, and Schorpp Reference Driscoll, Aydın-Çakır and Schorpp2024), we can now theorize the ways in which contextualizing courts’ environments in this way may inform citizens’ awareness and their subsequent demand for judicial independence.

Our cases represent divergent political contexts, from fully consolidated democracies like the US and Germany to backsliding democracies like Poland and Hungary. Nevertheless, these four countries are comparable cases. We focus on the public’s evaluation of each country’s highest constitutional court – the US Supreme Court, Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court, Polish Constitutional Tribunal, Hungarian Constitutional Court – and which all have the power to rule on whether national laws violate the constitution (Central Intelligence Agency n.d.a). While there are structural differences in each court, such as their jurisdiction, judge selection process, and legal system (Central Intelligence Agency n.d.a, n.d.b), we expect the mechanisms driving public opinion to be the same within similar national contexts – an expectation that is backed by previous research (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998). For example, despite the structural differences in each country’s judicial system, Aydın-Çakır and Şekercioğlu (Reference Aydin-Çakir and Şekercioğlu2016) utilize surveys from forty-nine countries and show that the public’s awareness of courts correlates with their confidence in the judiciary in systematic ways (cf. Driscoll, Aydın-Çakır, and Schorpp Reference Driscoll, Aydın-Çakır and Schorpp2024; Garoupa and Magalhães Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021). In democratic systems, awareness has a positive relationship with confidence in the courts, whereas in non-democratic systems, this relationship is reversed.

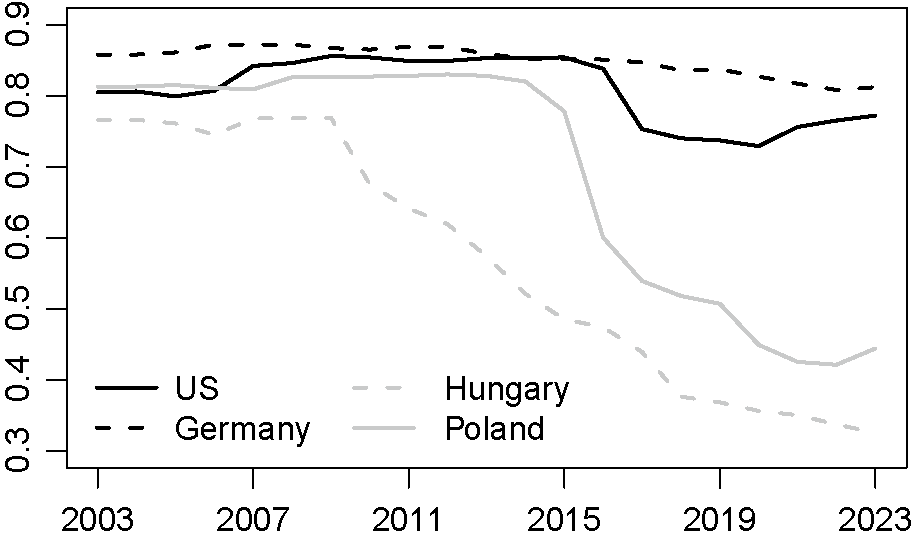

Figure 1 shows each country’s liberal democracy score from 2003–2023 using data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, God, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Krusell, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Paxton, Pemstein, Pernes, Rydén, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig, Wilson and Ziblatt2023; Pemstein et al. Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Medzihorsky, Krusell, Miri and von Römer2023).Footnote 12 During this time period, Germany’s score is consistently democratic without much temporal variation. The US measure aligns closely with Germany until 2016, when at the beginning of Donald Trump’s presidency, the US liberal democracy score dips and gradually declines before beginning to recover in 2020. Poland and Hungary, by contrast, show clear signs of democratic retrocession over this period of time. Beginning in 2009 for Hungary and 2015 for Poland, each country’s liberal democracy score begins to decline from their relatively high levels following their accession to the European Union in 2004. Poland’s steep decline corresponds with the Law and Justice (PiS) party taking control of the presidency and both parliamentary houses in 2015, while in Hungary, much of the democratic backsliding has occurred under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and the Fidesz party, who won a constitutional majority in parliament in 2010, and have enacted reforms to consolidate power ever since (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018, 190).

Figure 1. Liberal Democracy Index (V-Dem).

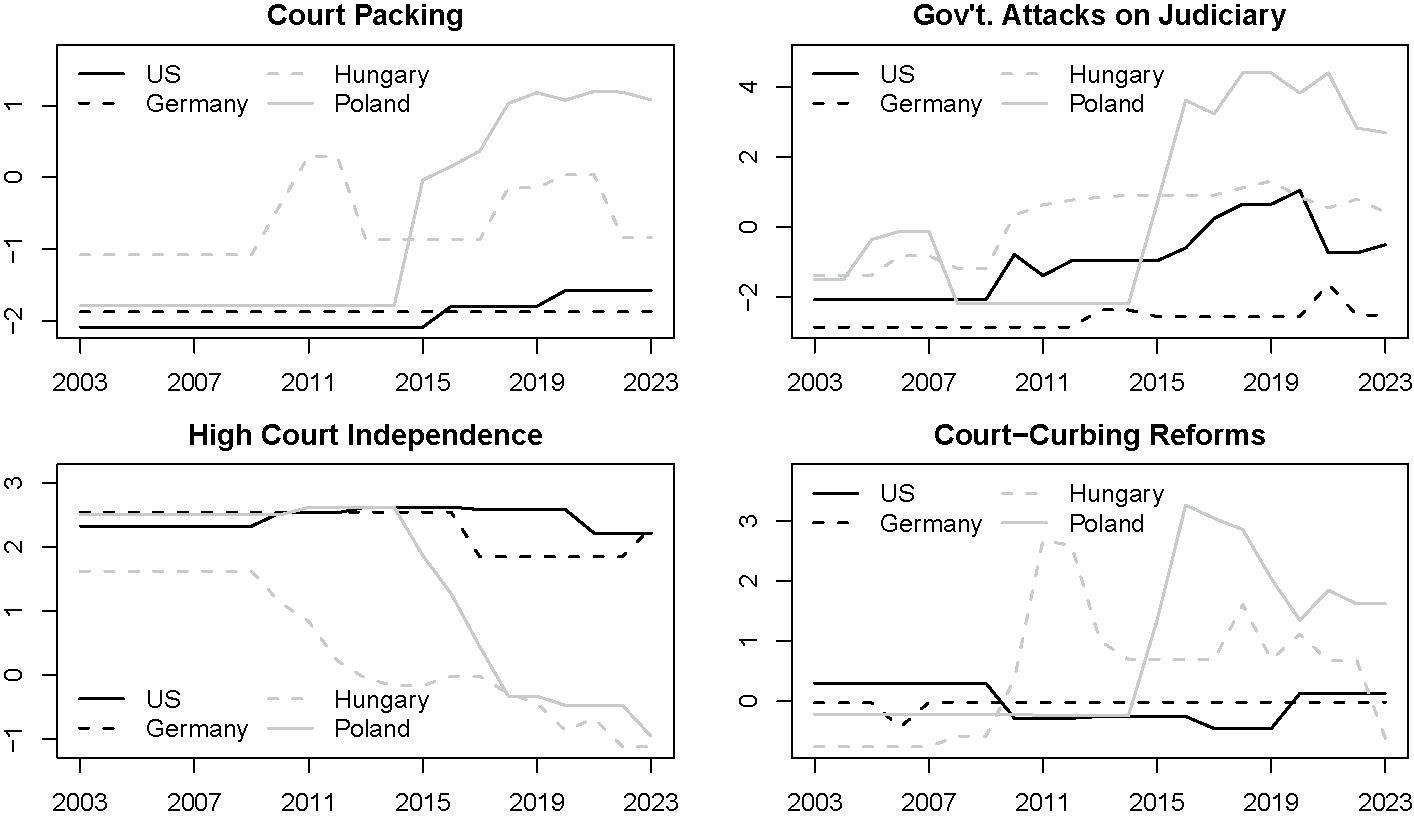

Figure 2 plots select V-Dem indicators related to the judiciary for the US, Germany, Poland, and Hungary from 2003–2023.Footnote 13 Although Figure 2 plots four democracies, there is substantial variation across their scores for the judicial indicators. Across these countries, residents have experienced a wide range of incumbent behavior toward the judiciary from exhibiting respect for the high court’s decisions in Germany, to reforming the judicial system’s institutional structure in Poland. Notably, the countries also differ in the severity of government attacks on the judiciary. Although ranking highly democratic on most judicial indicators, the US has experienced an increasing number of attacks on its judiciary, whereas Germany, the other consolidated democracy, has not. Overall, this descriptive evidence shows that, objectively, the countries differ in their levels of executive influence on the high court and judicial system. We exploit this contextual variation to explore the effect of our independent variables on citizens’ perceptions of the level of executive influence on the high court. Before we turn to our empirical analysis, we offer a brief discussion of each case below.

Figure 2. Select Judicial V-Dem Indicators (2003–2023).

The United States and Germany

The US and Germany are consolidated democracies with independent judiciaries, and thus represent hospitable contexts (Figures 1 and 2). In many ways, these countries represent archetypal cases of an independent court placing a credible check on the government’s power. The highest US court is the Supreme Court, which consists of nine justices who are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate; Supreme Court justices hold their position for life and have the power of judicial review (United States Courts n.d.). The highest constitutional court in Germany is the Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) (i.e., Bundesverfassungsgericht). The duty of the FCC is to “ensur[e] adherence to the Basic Law” especially when it comes to protecting fundamental rights (Bundesverfassungsgericht n.d). The FCC is comprised of two Senates composed of 16 justices total who serve a single 12-year term with forced retirement at 68 years (Bundesverfassungsgericht n.d). Formally, the Bundestag and Bundesrat are each responsible for electing half of the justices (Bundesverfassungsgericht n.d).

While partisan politicking certainly colors the nomination processes of the Supreme Court and FCC justices, once in office, jurists on both high courts enjoy a very high level of functional independence (Figure 2). While the Supreme Court justices enjoy life tenure, the judges serving on the FCC hold office for twelve years (no re-election permitted). Such long tenures indicate that the justices of both courts are quite insulated from pressures relating to their professional ambitions. More broadly, the V-Dem data in Figure 2 shows that both governments have generally refrained from implementing judicial reforms or packing the court – all practices that may undermine judicial independence. The main difference between the US and Germany lies in the number of government attacks made on the judiciary: while government attacks have been rare in Germany, Figure 2 shows that the US judicial system has seen an increase in the number of government attacks on the judiciary in recent years, and especially during 2015–2020. However, and despite these attacks and threats, the US, like Germany, remains a consolidated democracy with an independent Supreme Court.

Poland and Hungary

In contrast to the US and Germany, Poland and Hungary represent political environments that are hostile to the high court. Both countries have experienced democratic backsliding in recent years due in no small part to the drastic institutional changes to the judiciaries, which impede their ability to check the power of the executive (Figure 1). In Hungary, the Fidesz party, led by Prime Minister Orbán, won a two-thirds majority of Parliament, granting the Fidesz party the power to change the constitution; in Poland, the PiS party won the presidency and both houses of Parliament (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018). Once in power, both governments began successful campaigns to strip their constitutional courts of their independence, while “[c]laiming they were enacting the ‘will of the people,’ who felt betrayed by liberal democracy” (Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020). There are striking similarities across these cases as Poland adopted many of Hungary’s strategies to neutralize their judicial system’s ability to check the government’s power (Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020). Figure 2 illustrates the judicial democratic backsliding that first occurred in Hungary followed by Poland. Schemes to enhance the government’s power through court packing, judicial reform, and attacks on the judiciary abounded while the independence of the high court fell.

After winning a constitutional majority in Parliament, the Fidesz party immediately began undermining the Hungarian Constitutional Court’s independence (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018). An early step was to change the appointment process of justices: by bypassing consultation with the opposition, the power to appoint was placed solely in the government’s hand (Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020, 215). Other constitutional amendments increased the number of justices from eleven to fifteen; as these new positions were filled with pro-Fidesz justices, by 2013, these changes ultimately led to Fidesz’ capture of the Court (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018; Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020). Further amendments stripped the Court’s jurisdiction of certain financial decisions and constitutional amendments, and nullified the Court’s previous case decisions to be used as legal precedents (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018). These practices resulted in the stripping away of the Hungarian Constitutional Court’s judicial independence.

Years later, the PiS Polish government followed in Hungary’s footsteps, utilizing similar practices to undermine the judicial independence of its high court (Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020). The Polish Constitutional Tribunal, which consists of fifteen justices who serve a singular nine-year term (The Constitution of the Republic of Poland, arts. 187 and 194), was at the forefront of the PiS government’s attacks and reforms (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018; Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020). While it was the PiS party that was responsible for most of the democratic backsliding, their predecessors took the first strike (Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020). Following their electoral defeat to PiS, the Civic Platform unconstitutionally changed the power of Parliament to elect new justices ahead of an actual opening (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018). The Civic Platform government selected three justices in the old manner and two in the new manner. This attempt to rig the Tribunal “politici[z]ed the Court, weakened its legitimacy and prompted its eventual destruction by PiS, equipped with the argument that the Court is not impartial anymore” (Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020, 215). Indeed, upon assuming office, President Andrzej Duda refused to swear in the justices, opting instead to pack the court with five PiS justices (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018). The President of the Constitutional Tribunal refused to acknowledge the three illegal PiS justices, and in response, the PiS government enacted six laws which further undermined the Tribunal’s independence (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018). Following the term-limited exit of the President of the Constitutional Tribunal, the PiS cemented its capture of the Tribunal by placing one of its judges as the new President through a dubious election (Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018).

As these case studies demonstrate, the governments of both Hungary and Poland have taken systematic steps to undermine the independence of their pinnacle courts, which has been a defining feature of the consolidation of executive powers to the detriment of liberal democracy and the separation of powers. Indeed, these actions, along with other anti-rule of law policies, led the European Union (EU) to withhold billions in funding from both countries until their policies are brought into compliance with EU standards (Riegert Reference Riegert2023; Tamma Reference Tamma2023).Footnote 14

Theory and Hypotheses

Now that we have described our conceptualization of hostile versus hospitable contexts for judicial independence and categorized our cases, we turn to our theory. “Positivity Theory” argues that familiarity with courts exposes citizens to the so-called “legitimizing symbols” of justice, such as judicial objectivity and impartiality, and that this exposure leads individuals to regard judicial institutions as legitimate. Using cross-national data, work by Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998) documents that “generally there is a fairly strong tendency in most countries for the more aware to be more supportive of their national high court” (350).Footnote 15

Comparative research has largely underscored that context might matter to public perceptions of the court. Researchers have shown that individual political sophistication (as a proxy for awareness) is inversely related to confidence in judiciaries and judicial institutions outside the US and Western Europe (Salzman and Ramsey Reference Salzman and Ramsey2013; Aydın-Çakır and Şekercioğlu Reference Aydin-Çakir and Şekercioğlu2016). Scholars have reasoned that in these contexts, those among the public who are more aware of courts are also more likely to evaluate courts’ performance as deficient, and therefore more likely to express their skepticism through lower confidence. Garoupa and Magalhães (Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021) further argue that awareness should, in turn, moderate the relationship between institutional performance and public support: increases in awareness should strengthen the effect of judicial independence on public support, for example, be it positive or negative.

This paper aims to unpack the relationship between awareness and preferences for more judicial independence, considering the effect of individual-level predictors in diverging contexts where executives either do or do not reform the high court to suppress its judicial independence. We examine the conditions under which increased public awareness correlates with citizens’ demand for judicial independence. We expect that awareness informs public attitudes about judicial independence as well as citizens’ perceptions of such executive influence, but this effect will differ depending on the context.

We begin our argument by noting that, if the beliefs that aware citizens have about judicial institutions depend on the political and institutional environment (cf. Staton Reference Staton2010; Aydın-Çakır and Şekercioğlu Reference Aydin-Çakir and Şekercioğlu2016), then we should expect that awareness will correlate with different factors across different contexts. In particular, where courts frequently become the target of recalcitrant leaders, public awareness is more likely to be positively and strongly associated with perceptions of executive influence, despite the inclusion of other well-known correlates of citizens’ awareness of courts. In contrast, in environments where interbranch dynamics are more hospitable to courts, more aware individuals will know that executive interference is not the norm, such that awareness will be negatively correlated with perceptions of executive influence.Therefore, our first hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): In hostile political environments, awareness will correlate positively with perceptions of executive influence. In hospitable environments, awareness will correlate negatively with perceptions of executive influence.

Our theoretical framework and data also allow us to examine the determinants of public attitudes about courts’ independence from the executive. We are interested in how public demand for judicial independence correlates with both awareness and perceptions of executive influence across contexts. We first focus on the association between perceived incumbent influence and demand for judicial independence. We expect that as citizens’ perception of executive influence increases, they will demand more judicial independence, and more so in contexts where incumbents’ meddling is widespread.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Perceptions of executive influence will correlate positively with demand for judicial independence, but this correlation will be stronger in environments where environments are hostile.

Next, we examine the relationship between awareness and public demand for judicial independence. In more hospitable environments, where judicial institutions are less likely to be the target of court-curbing reforms, we expect that awareness will be positively correlated with demand for judicial independence – even when we control for perceptions of executive influence on courts’ decisionmaking (H2). It is precisely in these contexts that what more-aware citizens learn about courts is unlikely to be influenced by leaders’ tampering with judicial institutions. These are also the environments in which previous research has suggested that this Positivity Bias is likely to hold (Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014).

In contrast, where courts are frequently the target of incumbent meddling, increased awareness should not correlate with demand for judicial independence once we control for citizens’ perceptions of executive influence. We expect this is so because the information that aware citizens are exposed to in these contexts is shaped by unfavorable interbranch dynamics. That is, in environments particularly hostile to judicial institutions, court awareness begets more knowledge about incumbents’ interference with the judiciary. We expect that in such hostile contexts, citizens’ awareness of the court increases in tandem with their perceptions of the political executive’s influence. Thus, once we account for the latter (perceptions of executive influence), awareness should not be independently correlated with public demand for judicial independence. This logic motivates the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): In hospitable political environments, awareness will correlate positively with demand for judicial independence, even when controlling for perceptions of executive influence. However, in hostile environments, awareness will not correlate with demand for judicial independence after accounting for perceptions of executive influence.

Finally, we hold expectations about how perceptions of executive influence moderate the relationship between awareness and public demand for judicial independence across contexts. In environments more hospitable to courts, Positivity Bias Theory suggests that more-aware citizens hold more positive beliefs about judicial institutions and therefore demand more judicial independence (H2). Yet, we argue that such preferences are conditional on individuals’ perception of executive influence on the court. That is, the loyalty that more-aware citizens develop toward judicial institutions will strengthen as they perceive greater incumbent influence. Similarly, if aware individuals do not perceive executives to influence courts’ decision-making, the effect of awareness on demand for judicial independence will be smaller.

In contrast, we expect that where courts are frequently the target of incumbent interference, any association between awareness and demand for judicial independence will not depend on public perceptions of executive influence. The logic for this expectation is related to our discussion of H2. If being more aware in these hostile environments implies that citizens have formed their beliefs about courts mainly on the basis of observing court-curbing by incumbents, then the effect of awareness on demand for judicial independence should not vary across perceptions of executive meddling. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): In hospitable environments, perceptions of executive influence will moderate the correlation between awareness and demand for judicial independence: this correlation will be stronger amongst those who perceive greater incumbent influence on the court. In hostile environments, by contrast, the association between awareness and demand for judicial independence will not depend on perceptions of executive influence.

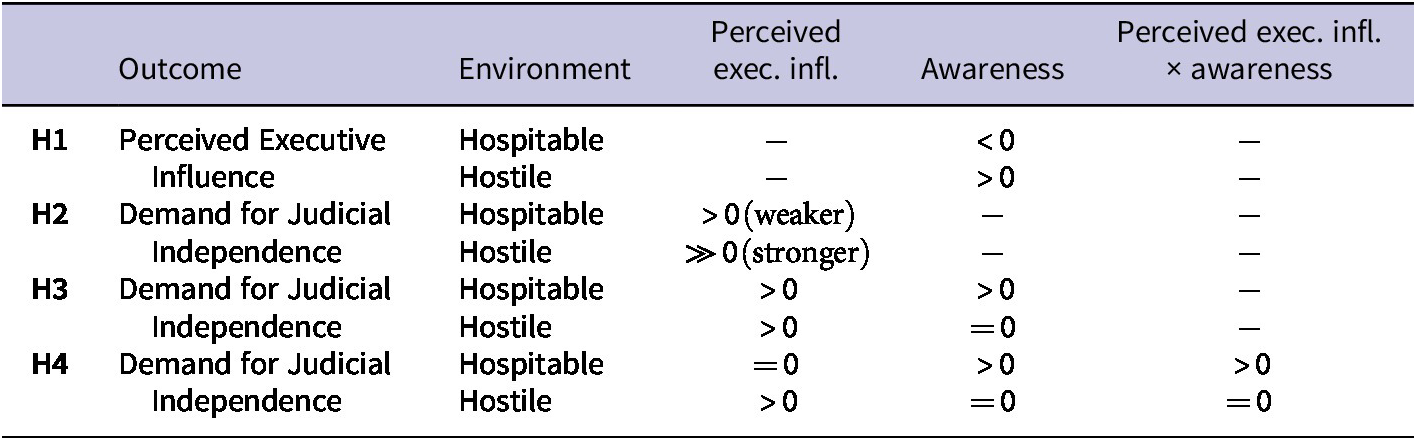

Table 1 summarizes our hypotheses.

Table 1. Summary of Hypotheses

Descriptive Evidence

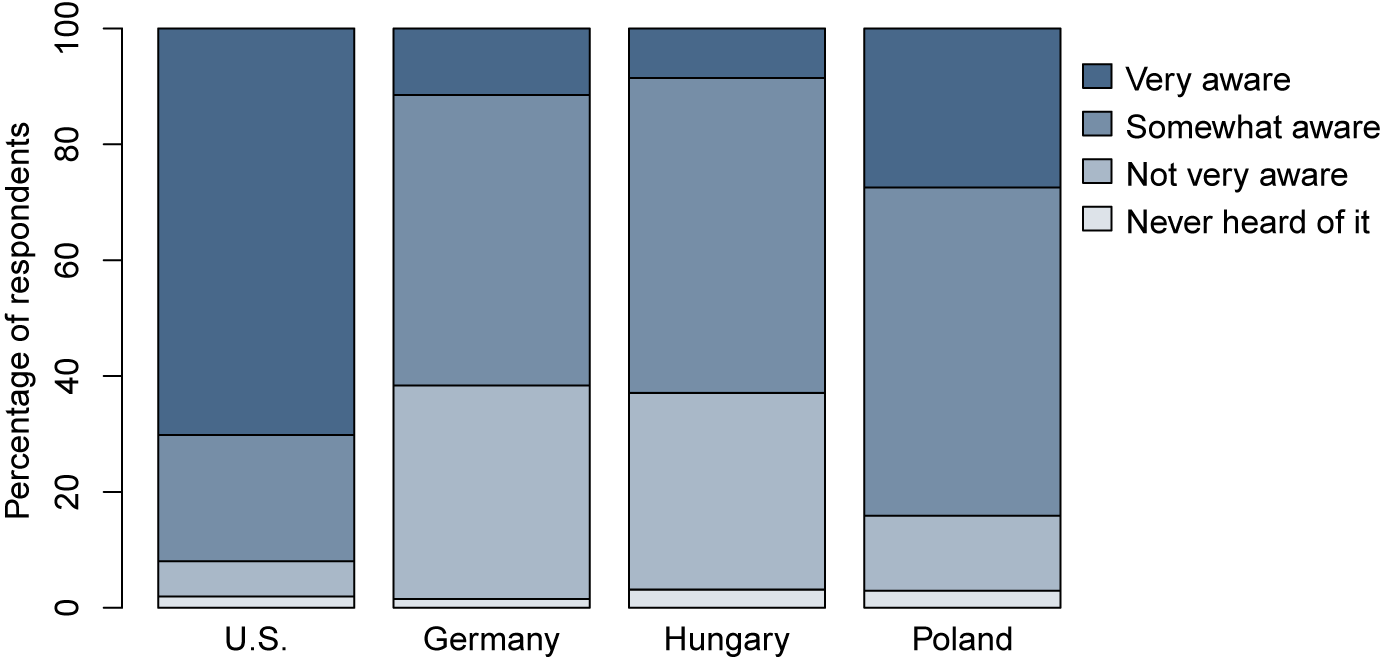

We start by considering the descriptive variance across our four countries in light of the theoretical expectations outlined above. Following extant work (i.e., Gibson Reference Gibson2007), we operationalize this important concept using a well-established survey item (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003), which directly queries subjects “To what extent are you aware of the [proper name of the high court]?” Respondents’ self-reported awareness is measured on a four-point scale, ranging from “very aware” to “have never heard of.”Footnote 16

Figure 3 shows the distribution of awareness across the four countries, with several sources of interesting variance. First, we do not observe a clean correlation between awareness and the institutional environment: although the German court is a quite prominent player in the constitutional order of that country, still nearly 50% of Germans describe themselves as not very aware of the FCC. In Poland, by contrast, the hostile institutional environment may well have bolstered awareness of the court – with more than 80% of respondents expressing they are somewhat or very aware. Second, the US public is unusual in its level of awareness, with an absolute majority of Americans reporting they are very aware. This finding cements this case as atypical in this regard (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998), but also likely rooted in the timing of our survey, which was fielded in the final days of June and the first week of July of 2021, following the announcement of the Court’s highest profile cases for that term.Footnote 17

Figure 3. Awareness of High Court by Country. Note: Distribution of answers to the question “Would you say that you are very aware, somewhat aware, not very aware, or have you never heard of the [High Court], that is, one of the [Country] courts?”

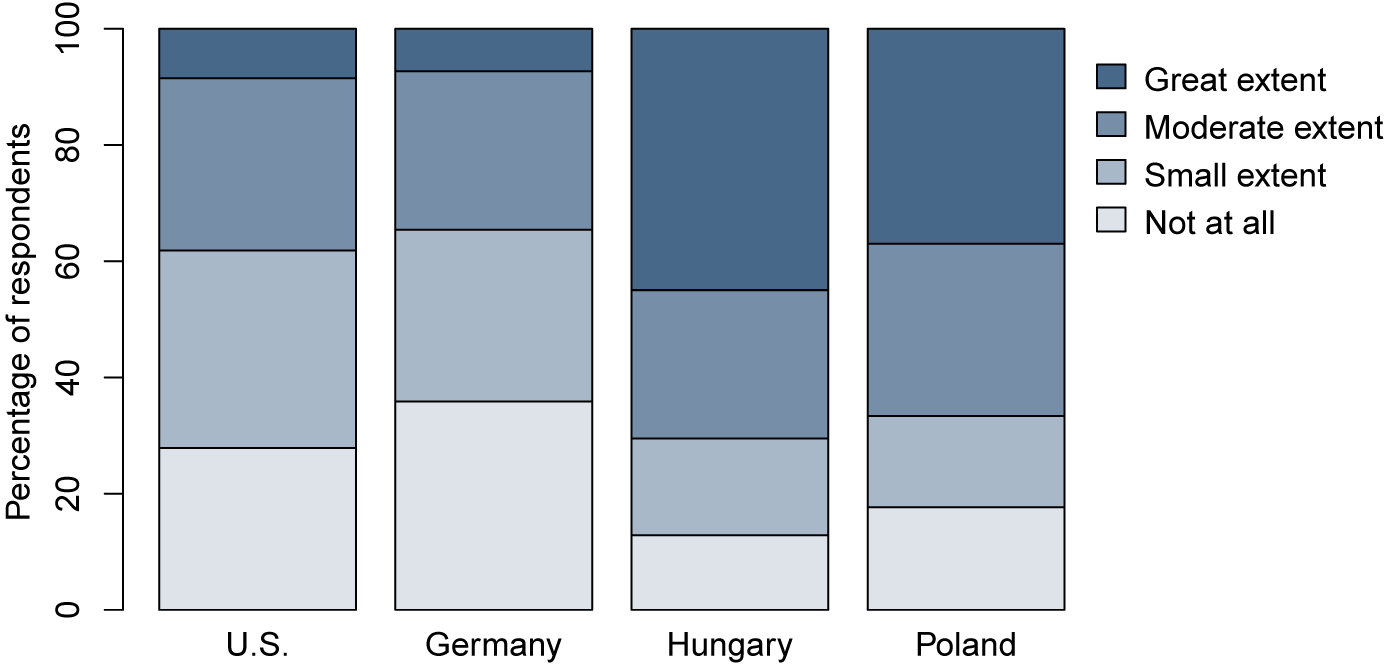

We now turn to the distribution of our two variables of particular interest. Perceived Executive Influence measures citizens’ perception of the level of executive influence on the high court. In the US context, for example, this is measured by a survey question which asks, “To what extent do you think the president influences the rulings that the US Supreme Court makes?” where respondents answered “A great extent,” “A moderate extent,” “A small extent,” or “Not at all.” When looking at the distributions of this variable (Figure 4), immediately evident are the differences in public perceptions regarding executive influence that comports with the case descriptions and the V-Dem data described above.

Figure 4. Perceived Executive Influence by Country. Note: Distribution of answers to the question, “To what extent do you think the [Executive] influences the rulings that the [High Court] makes?”

Whereas approximately one-third of Germans and Americans (35.9% and 27.9%, respectively) report no executive influence in their respective high courts, these percentages are nearly halved in Hungary and Poland (17.7% and 12.9%, respectively). About 60% of German and American respondents reported minimal (a “small extent” or “none”) executive influence in the high court decision-making. Conversely, an absolute majority of Hungarians (70.5%) and Poles (66.6%) describe executive influence of their constitutional courts to be considerable (either “moderate” or a “great” extent), thus a wide plurality of respondents in both cases suggest the executive is very influential in the high courts’ work. In the US and Germany, by contrast, less than 10% of respondents reported a great extent of executive influence in the high court’s functioning. These individual-level diagnoses of executive influence align with the objective measures of judicial indicators from V-Dem, and the case studies which document the degree of executive interference on the courts.Footnote 18 As Germany and the US have experienced less, if any, executive interference on the high courts, it is not surprising that their citizens perceive the court to be freer from influence than Hungarians and Poles, who have witnessed years of executive tampering.

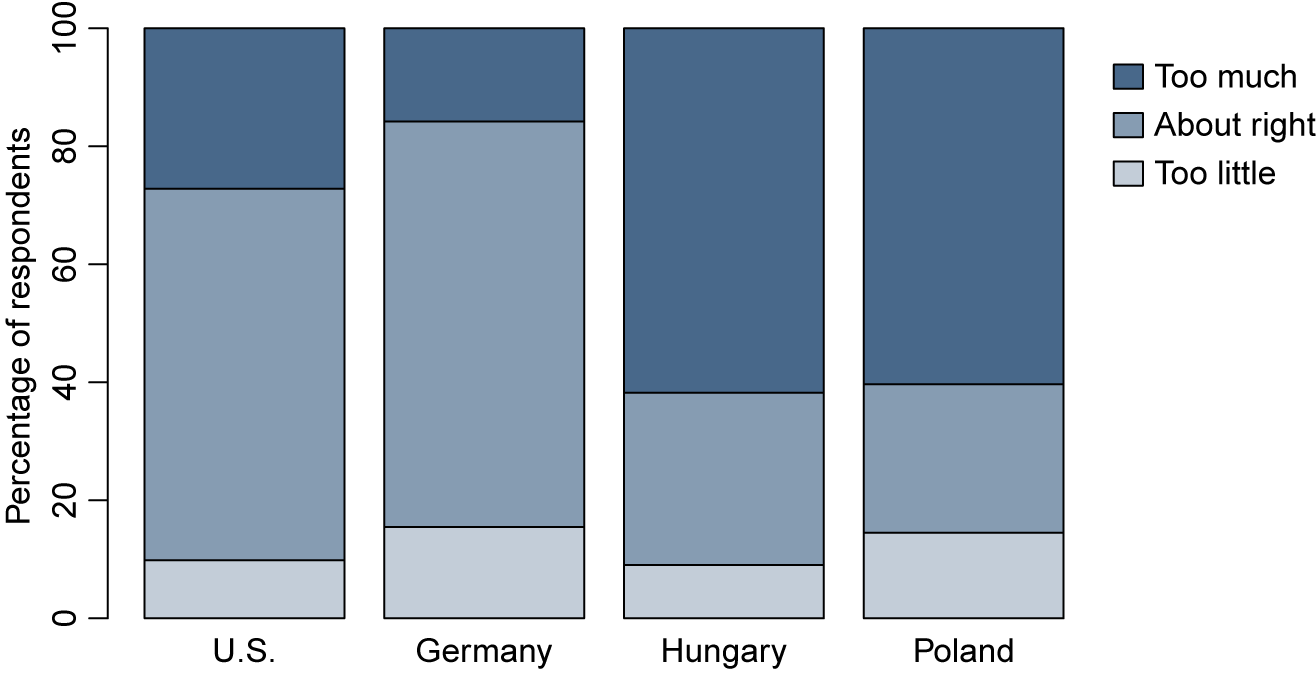

Our second original survey question asks respondents about their preferred level of executive influence – a measure that shifts away from the public’s assessment of their political environment to what they believe should happen.Footnote 19 Returning to the US context, this is measured by the survey question, “Do you think the president has too much, too little, or about the right amount of influence on the US Supreme Court?” We conceptualize this measure as Demand for Judicial Independence, where responses indicating that the executive has “too much influence” correspond to higher values of this variable (and thus greater demand for judicial independence), responses indicating that the executive has “about the right amount of influence” correspond to middle values, and responses indicating that the executive has “too little influence” correspond to lower values.Footnote 20

Turning now to Figure 5, we visualize the distribution of the public’s demand for judicial independence. Again, the effect of national context is immediately apparent in this outcome. 68.7% and 63% of Germans and Americans, respectively, are less demanding of judicial independence, reporting that the level of desired executive influence is “about right” in their opinion. This is compared to only 29.2% and 25.1% of Hungarians and Poles, respectively. The absolute majority of respondents in these countries report that there is “too much” executive influence. However, how we interpret respondents’ demand for judicial independence is context-dependent and warrants further scrutiny. As the majority of Hungarians and Poles perceive executive influence (Figure 4), it is possible that the same absolute majority who perceive executive influence in the judicial context are those who demand less judicial independence and therefore are complicit supporters of executive influence on the court; these may be those among the public whose lack of faith in judicial institutions prompts elites to attack the court in the first place (Clark Reference Clark2009). Conversely, it may be that those who perceive executive influence are also those who demand greater judicial independence. As for Americans and Germans, a large proportion of respondents are satisfied with the status quo level of executive influence, irrespective of whether they see the executive as influential or not. As such, we have more to unpack to understand how the public’s perception of executive influence informs their attitudes about what should happen in practice.

Figure 5. Demand for Judicial Independence by Country. Note: Distribution of answers to the question, “Do you think the [Executive] has too much, too little, or about the right amount of influence on the [High Court]?”

Clearly, the diverging distributions of the outcome variables across these four cases underscores that the hostile versus hospitable nature of the national context matters when examining public support for judicial institutions. The outcome variables we interrogate here give previously inscrutable insights into what the correlations between awareness and public support for courts actually mean. We now turn to the individual-level analyses of these data.

Research design and results

We test our hypotheses using linear regression models. First, to test H1, we regress Perceived Executive Influence on Awareness. We report the bivariate relationship as well as models that include a vector of control variables: Knowledge, Diffuse Support, Specific Support, Partisanship (Gov. Supporter), Ideology, Political Interest, support for a Strong Leader, as well as Age and Gender. Footnote 21 Table 2 presents the results.

Table 2. Determinants of Perceived Executive Influence

Note: Robust (heteroskedasticity-consistent) standard errors in parentheses.

+ p

![]() $ < $

0.1; * p

$ < $

0.1; * p

![]() $ < $

0.05; ** p

$ < $

0.05; ** p

![]() $ < $

0.01; *** p

$ < $

0.01; *** p

![]() $ < $

0.001

$ < $

0.001

Recall that H1 expected that increased awareness would correlate positively with respondents’ perception of executive influence in contexts where executive interference is commonplace, as those who are more aware of the court in such environments are more likely to be exposed to such interbranch dynamics. The coefficient on Awareness in Table 2 provides evidence in support for this hypothesis. For both Poland and Hungary (models 5–8), this estimate is positive and statistically different from zero (p < 0.001), even when controlling for a large set of predictors of attitudes about judicial institutions. This finding implies that awareness goes hand in hand with perceptions of executive influence in these environments.

Yet importantly, the results are mixed in the US and Germany. H1 suggested that awareness would correlate negatively with perceptions of executive influence in these hospitable environments. The bivariate estimations (models 1 and 3) support this expectation, indicating a negative, statistically significant correlation between awareness and perceptions of executive influence. However, in the models with controls (models 2 and 4) these estimates are positive, weaker, and statistically insignificant at conventional levels (p ≈ 0.07 in the US and p ≈ 0.34 in Germany).Footnote 22

These strong positive correlations in Hungary and Poland – and negative or weak-to-nonexistent correlations in the other two countries – suggest that contextual factors shape what it is that more aware people “learn” about when they are more attentive to courts. More specifically, this finding provides consistent evidence that in hostile environments, incumbents’ unruly behavior toward courts forms the impression (among those most aware) that the courts are subject to executive influence. In environments more hospitable toward courts, bivariate models suggest that respondents are less likely to perceive executive influence – yet this association becomes positive (although insignificant at conventional levels) when we include other predictors of attitudes about judicial institutions.

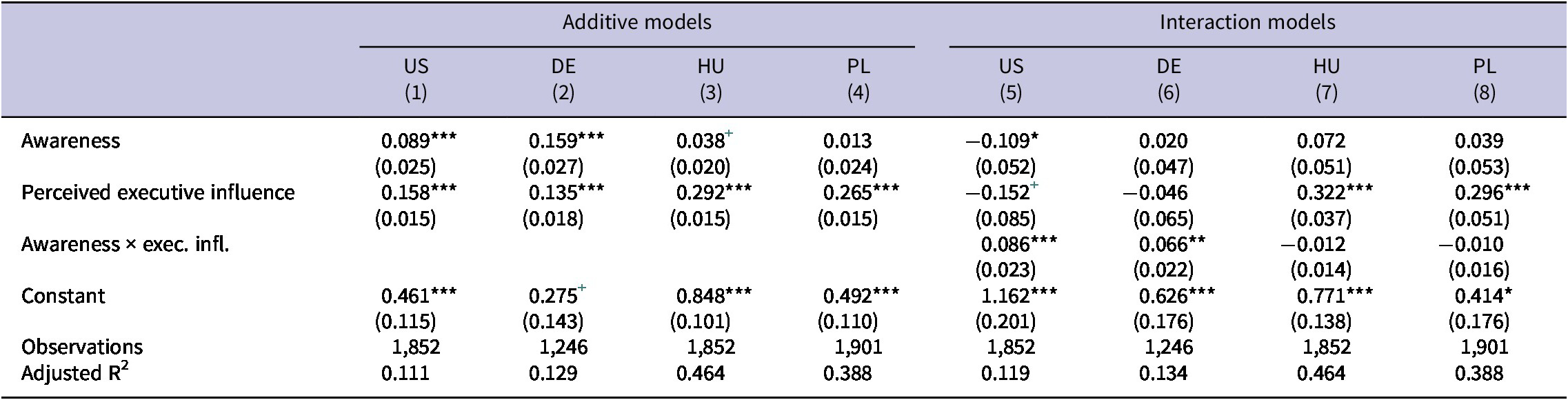

We turn now to H2 and H3. In models 1–4, we fit linear models that regress Demand for Judicial Independence on Awareness and Perceived Executive Influence as well as controls. To test H4, we additionally estimate models that include an interaction between our main predictors (models 5–8). The results are shown in Table 3.Footnote 23

Table 3. Determinants of Demand for Judicial Independence

Note: Controls: Diffuse Support, Specific Support, Partisanship (Gov. Supporter), Ideology, Political Interest, Strong Leader, Knowledge of the Court, Age, and Gender. See Appendix Table C1 for full regression results. Robust (heteroskedasticity-consistent) standard errors in parentheses.

+ p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

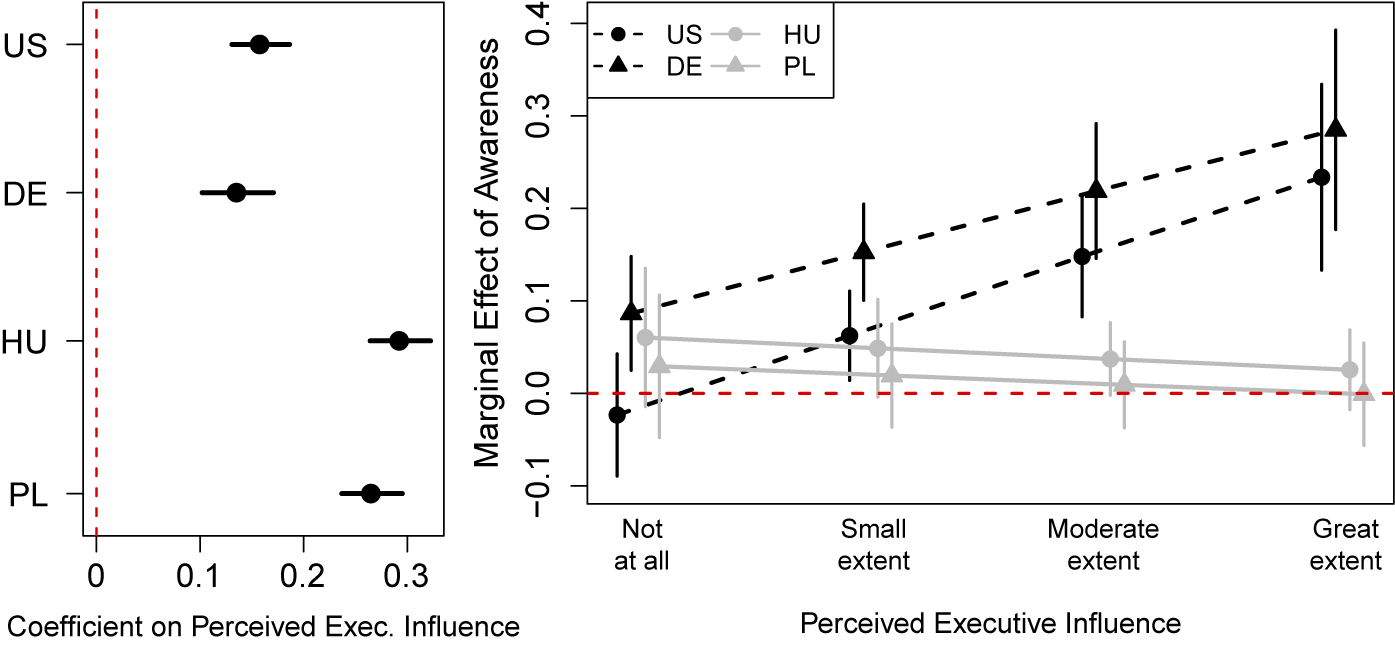

We start by discussing models 1–4, which support our theoretical expectations with respect to H2 and H3. First, the coefficient on perceived executive influence is positive and statistically significant in all countries (p < 0.001), all other factors constant. This result is consistent with H2 and suggests that, as individuals perceive greater executive influence on their high court, they are more likely to demand more judicial independence from the executive. Moreover, also in line with H2, this association is nearly twice as strong in Poland and Hungary as it is in the US and Germany. This is also shown in the left panel in Figure 6, which plots coefficient estimates for perceived executive influence and corresponding confidence intervals.Footnote 24

Figure 6. Effect of Perceived Executive Influence and Awareness on Demand for Judicial Independence. Note: The left panel plots the coefficient estimate on Perceived Executive Influence (Table 3, Models 1–4). The right panel shows the marginal effect of Awareness across values of Perceived Executive Influence (Table 3, Models 5–8). Lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Second, the coefficients on awareness provide further evidence of context-driven differences, as expected by H3. Indeed, models 1–4 indicate that, once we control for perceptions of executive influence, the association between awareness and demand for judicial independence is weak and not statistically significant at conventional levels in Hungary (p ≈ 0.08) and Poland (p ≈ 0.61), but is positive and significant in the US and Germany (p ≈ 0.001). This suggests that, in political environments hostile to courts, increased public awareness is at best only weakly associated with attitudes about judicial independence. Instead, in those countries, citizens’ perception of executive interference is the stronger predictor of demand for judicial independence. In contrast, where citizens are not exposed to incumbent interference with courts (as in the US and Germany), increased public awareness is correlated with greater demand for judicial independence.

Finally, models 5–8 in Table 3 provide further evidence in support of our expectations. Recall that H4 suggested that perceptions of executive influence would moderate the association between awareness and preferences for judicial independence, but only in environments more hospitable for courts. The interaction coefficients in models 5–8 show exactly this dynamic: the interaction, Awareness × Exec. Infl., is positive and statistically significant in the US and Germany – suggesting that the correlation between awareness and demand for judicial independence is increasing on perceived executive influence – but not in Hungary and Poland – indicating that the effect of awareness does not change across perceptions of incumbent influence. The right panel of Figure 6 graphically visualizes this conditional relationship.

Discussion

We advance the study into the contextual conditions under which awareness might influence public attitudes about judicial institutions in positive, legitimacy enhancing ways. Previous research has consistently observed that where courts function as they are supposed to, individuals that are more aware of judicial institutions lend greater levels of support. In turn, where judicial power falters or is directly under threat, greater public awareness is associated with a general skepticism toward pinnacle courts, and a loss of trust and confidence in judicial authorities. Those who come before us have suggested that this increased awareness (and increased political sophistication) “works” in different contexts owing to citizens’ differing ability to accurately evaluate the institutional qualities and performance of their courts (Staton Reference Staton2010; Aydın-Çakır and Şekercioğlu Reference Aydin-Çakir and Şekercioğlu2016; Garoupa and Magalhães Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021).

In line with some of this previous research, we find that awareness correlates with preferences for more judicial independence where executives do not frequently meddle with courts (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014). Yet, in contrast to most prior work, our results indicate that both perceptions of executive interference and increased awareness can in fact boost citizens’ support for judicial power, by evoking an increased demand for more judicial independence. This effect is pronounced in – and arguably most important in – hostile contexts where existing research predicts public support is faltering: where incumbent attacks are frequent, the public is skeptical of judicial authorities, and judicial legitimacy is most imperiled. Although in these hostile contexts, executive interference may foster the public’s mistrust of courts (Aydın-Çakır and Şekercioğlu Reference Aydin-Çakir and Şekercioğlu2016; Garoupa and Magalhães Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021), we show here that this coexists with a demand for increased judicial independence, and a reduction of executive influence. This is consistent with other work that has argued that public attitudes about courts are a result of court-curbing and interbranch antagonism (Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2023b; Driscoll, Aydın-Çakır, and Schorpp Reference Driscoll, Aydın-Çakır and Schorpp2024), rather than being a fundamental cause thereof (Clark Reference Clark2011).

Our research can also inform discussions about the determinants of support for judicial independence in the most hospitable environments. In such contexts, perceptions of executive influence play a role in explaining greater demand for judicial independence. Specifically, we provided evidence that the association between awareness and demand for judicial independence depends on the extent to which the public perceives executive interference: when citizens are queried about the proper level of judicial independence, they articulate this opinion with reference to their beliefs about leaders’ meddling with courts – even if such influence is objectively minimal, as it is in contexts like Germany and the US.

Finally, in terms of research design, our paper makes several contributions to the study of public support for and evaluation of the judiciary. Using a pair of original survey questions, we shift the focus beyond extant measures of diffuse support to bolster our understanding of public opinion on interbranch conflict, particularly whether executive interference in the high court is tolerated by the public. As others have done before us (Achury et al. Reference Achury, Casellas, Hofer and Ward2023; Bartels, Horowitz, and Kramon Reference Bartels, Horowitz and Kramon2023; Krewson and Masood Reference Krewson and Masood2024), we move beyond the standard battery of diffuse and specific support, and in contexts that have long been neglected in public opinion research regarding judicial power. Our research aimed to fill these gaps by introducing novel measures and studying public tolerance for court-curbing by the executive across four countries which vary greatly in their hostility versus hospitality to the institutional power of courts. We certainly hope that continued scholarly inquiry in this realm will continue to better understand the public’s evaluation and support for judicial institutions as it varies across time, contexts, and individuals.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2024.20.

Data availability statement

All replication materials are available on the Journal of Law and Courts Dataverse archive at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OXYBS5.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maureen Stobb and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Financial support

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. SES-2027653, SES-2027671, and SES-2027664. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. We thank the Rapoport Family Foundation and FSU Department of Political Science for their financial support.

Competing interest

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.