Introduction

This article focuses on Nigeria and its problems of access to education and argues that it has historical challenges over access to schooling that overshadowed the need to streamline the purpose of education. Amid Nigeria’s obligation in international human rights law (IHRL), this article discusses the problem of access to education as a common denominator in all the E-9 countries. The E-9 countries are the nine most populous countries in the world with over two-thirds of the world’s illiterate adult population, especially in women and girls, and over half of the world’s out-of-school children.Footnote 1 Nigeria itself has notable challenges over access to education, especially for children, girls and women, and over meeting the quality of education needed to fight illiteracy.Footnote 2 Nigeria is the focus of this article for several reasons. Firstly, it is the only sub-Saharan African state that is an E-9 country. Secondly, it has ratified most of the key international treaties on human rights and the specific treaties on education, providing, therefore, a good example of how the human rights purpose of education could be realized domestically and the corresponding treaty obligations. Thirdly, it is the most populous sub-Saharan African country, with a high proportion of children under 15 years old and, therefore, has many young citizens who require access to education.Footnote 3 Fourthly, and perhaps connected to these features, Nigeria ignored human dignity as the human rights purpose of education in the Constitution and legal mechanisms that control education and therefore is facing significant challenges in addressing the problems of access to schooling through a robust educational system.

This article endeavours to establish a clear nexus between access to education and the pursuit and achievement of human dignity as the human rights purpose of education. It will analyse the purpose of education in the legal mechanisms Nigeria adopted to comply with its obligations.Footnote 4 This will arguably reveal that while Nigeria has formally taken steps to incorporate relevant IHRL values, they are insufficient and cannot provide the leverage needed to address the problems of access to education that started in about 1842. It argues that recognizing the human rights purpose of education (human dignity) could spotlight the basic significance of access to education in determining the quality of human life as people born with inherent dignity.Footnote 5

This article, while using “education” interchangeably with “schooling”,Footnote 6 develops in three stages. Firstly, it provides the historical background of Nigeria’s problem of access to education and argues that the Constitution’s non-recognition of the human rights purpose of education has not helped tackle this perennial challenge. Secondly, it identifies Nigeria as an E-9 country, which without doubt evidences that it has considerable domestic problems of access to education and details Nigeria’s human rights responsibilities in accordance with the normative standards set under IHRL, especially its duty to promote universal access to schooling. Lastly, it critically examines the purpose of education in the legal mechanisms that control education in Nigeria and argues that these legal instruments are insufficient to address the perennial challenges of access to schooling as an E-9 country.

Access to education as a problem with historical significance in Nigeria

It is argued here that Nigeria has a historical problem of education delivery dating back to 1842, with manifestations in low access to schooling. The missionary societies brought formal education alongside the Christian religion into Nigeria’s heterogeneous society in 1842, and while the southern region embraced Christian faith-based education, the northern region, whose population is predominantly Muslim, rejected it, leading to problems of access to schooling. This marked the origin of challenges in education, and it is argued that, because of cultural heterogeneity, Nigeria could neither constitutionally nor legally recognize a purpose education will seek to achieve, which would have helped drive the trajectories of education delivery. It has been argued that human dignity is the human right purpose of educationFootnote 7 following article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and, as such, it is the responsibility of states to ensure education is directed to the achievement of everyone’s human dignity. In doing so, an efficient constitutional mechanism that explicitly stipulates the purpose of education will be advantageous. This section progresses in two stages. The first discusses the perennial challenge of access to schooling in Nigeria starting from 1842 and attempts to justify the choice of focusing on Nigeria. The second argues that Nigeria’s Constitution, from its historical development, ignored the purpose of education and in so doing could not recognize human dignity as the human right purpose of education.

Nigeria’s early challenges of access to education, 1842–1999

This subsection attempts to give a brief historical picture of educational challenges in Nigeria from 1842 to 1999 when Nigeria returned to democracy and argues that the problems of access to education remained a significant characteristic of Nigeria’s education system starting from 1842 when the missionary societies started establishing what were called mission schools. It argues that Nigeria’s inability to recognize the centrality of human dignity (the human rights purpose) in education delivery through explicit constitutional provisions may have contributed to its failed attempt as a populous and young democratic country with diverse cultural heterogeneity to address problems of access to education in 1970 through taking over education administration from the missionaries, in 1976 through the introduction of the universal primary education (UPE) scheme, in 1979 through the inclusion of education matters in the Constitution for the first time and in 1999 through constitutional codification and the launch of universal basic education (UBE). It is argued here that, because of the early education challenges and the circumstances suffusing formal education development within this period, the importance of institutionally setting a purpose education will seek to achieve became relegated and this contributed to conditions within the education sector that precipitated Nigeria’s inclusion in the E-9 countries in 1993.

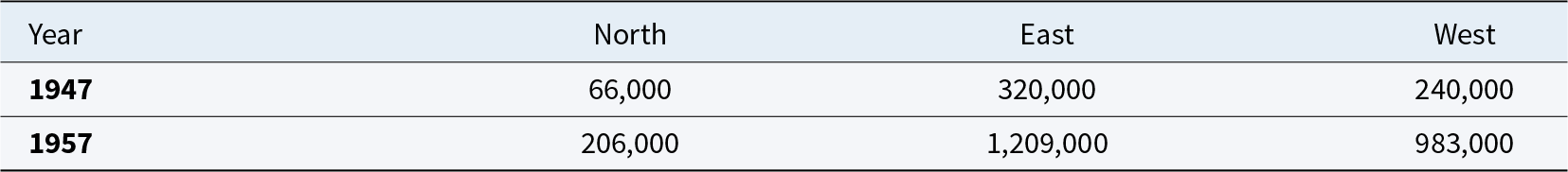

In Nigeria, formal primary education was introduced by the Christian missionaries in the mid-19th century.Footnote 8 The first of the missionary schools was founded by Methodists in 1843. The Anglican Church missionary society established schools in the early 1850s, followed closely by the Roman Catholics.Footnote 9 In 1861, the British colonial government established the colony of Lagos, and, in 1872, started giving aid grants to the missionary societies running the schools.Footnote 10 At this time, education curricula were largely mixed with the Christian faith, which marked the beginning of problems in education because the predominantly Muslim northern region rejected this pattern of education. Later, the colonial government intervened in education administration through the 1882 Education Ordinance which covered the Gold Coast (Ghana).Footnote 11 The failure of the 1882 Education OrdinanceFootnote 12 led to the 1887 Education Ordinance.Footnote 13 However, by 1914, when the northern and southern protectorates were amalgamated to form the present Nigeria, there were “fifty-nine government and ninety-one mission primary schools in the South”.Footnote 14 There are many views on the circumstances at this time, particularly regarding statistics; however, according to the leading account of Aliu Babatunde Fafunwa, a former minister of education, Hans Vischer,Footnote 15 an ex-Anglican missionary, was mandated by the British colonial government to establish a non-Christian faith-based primary education system for the northern region in 1909. By 1914 there were 1,100 primary school pupils in the protectorate of the North, which was still far below the 35,700 in the southern region.Footnote 16 37 years later, in 1951, the Macpherson Constitution created three regions (northern, eastern and western),Footnote 17 all of which tried to implement primary education schemes that appear to have worsened access to education across Nigeria.Footnote 19 There were notable problems with access to schooling and compulsory primary school enrolment disparities as illustrated in Table 1.Footnote 20

Table 1. Compulsory primary school enrolment disparities between the three regions in Nigeria, 1947–57Footnote 18

These figures show extensive challenges of access to schooling across the three regions, though each had parallel compulsory education schemes and there was no effort to stipulate the purpose education delivery will seek to achieve at this time. However, the problem of access to schooling did not abate as many children were still out of school. In 1970, because of manifest administrative shortcomings in the education sector and perennial low access to schooling, the government took over primary and secondary school management from the missionaries. In September 1976, the government in Nigeria launched the UPE programme, which was designed to promote increased access to schooling within Nigeria’s then 19 states.Footnote 21 Later, in 1979, as a result of heavy financial strains on the federal government, without robustly increased access to schooling, the Nigerian government transferred primary school administration and funding to states and local government councils, marking the decentralization of education amongst different tiers of government.Footnote 22 In a recent report, the UBE Commission noted that “[b]y 1979, the burden became too heavy for the federal government to bear alone. As a result, it ceded some of the responsibilities to State and Local Governments which also could not cope. This marked the beginning of the problems of primary education in Nigeria”.Footnote 23

The problem of very low primary school enrolment continued throughout the Federation of Nigeria.Footnote 24 Also in 1979, educational matters were for the first time made part of the text of Nigeria’s Constitution as “objectives”.Footnote 25 It provided for educational objectives under part II of the Constitution as “Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy” (FODPSP).Footnote 26 The Constitution Drafting Committee (CDC) in their report, while justifying the inclusion of the FODPSP in the 1979 Constitution, said “[g]overnments in developing countries have tended to be preoccupied with power and its material prerequisites … Such is the preoccupation with power and its material benefits that ideals as to how society can be organized and ruled to the best advantage of all hardly enter into the calculation”.Footnote 27

The CDC, in trying to explain the FODPSP, noted:

By Fundamental Objectives, we refer to the identification of the ultimate objectives of the Nation whilst Directive Principles of State Policy indicate the paths which lead to those objectives. Fundamental Objectives are ideals towards which the Nation is expected to strive whilst Directive Principles lay down the policies which are expected to be pursued in the efforts of the nation to realize the national ideals.Footnote 28

It is clear from the above explanation of the CDC that the inclusion of education under the FODPSP was only meant to be a policy objective tied to the political will of the government in power, and not to either confer any entitlement to individuals, ie an enforceable claim or right, or explicitly provide for the purpose of education. This is in tune with the dominant neo-liberal policies at this time, which rely on market solutions, and for this reason, the provisions of the FODPSP under chapter II of the 1979 Constitution were repeated simpliciter in the current 1999 Constitution.

Notably, the inclusion of education matters in the text of the 1979 Constitution could not in itself improve access to schooling across Nigeria. On 30 November 1999, the introduction of the UBE scheme marked another attempt, after the failure of the UPE plan in 1976, to increase access to schooling.

In sum, while formal education gained acceptance in the southern region, it was rejected across all the northern states that are predominantly Muslim and this became a strategic factor that overshadowed the need to have a universal purpose of education in Nigeria, even in the 1979 Constitution. That is to say, the multicultural nature of Nigeria’s society and the fear of advancing a purpose of education that will promote a particular religious belief, eg the Christian religion, became a barrier to having a universal purpose of education in Nigeria. Because of the widespread lack of access to compulsory schooling that culminated in high levels of illiteracy, particularly among women and girls, UNESCO in 1993 included Nigeria in the E-9 countries.Footnote 29 The Constitution did not help provide the legal platform to drive education delivery; in particular, it could not provide for the purpose education will seek to achieve. In what follows, the educational provision under Nigeria’s Constitution and the purpose it is meant to achieve is critically examined.

Nigeria’s Constitution ignores the purpose of education

It is argued that educational provisions in Nigeria’s Constitution could not recognize education as everyone’s human right, which is an essential prerequisite for recognizing the central significance of human dignity. Hence, this paper argues that the provisions for education in Nigeria’s Constitution, especially the current 1999 Constitution, have no clear purpose and, as such, ignore human dignity as the human rights purpose of education; this has not been helpful considering Nigeria’s status as an E-9 country. It is argued that both the 1979 and 1999 Constitutions ignored the purpose education will focus on achieving, which is standard practice under IHRL, and this may have created a constitutional lacuna. For instance, article 26(2) of the UDHR, article 13(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and article 29(1) of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) provide for the purpose of education as a standard of achievement for all states, including Nigeria. The preamble to the UDHR declared that the requirements of IHRL, especially those declared under the UDHR, serve “as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations”. Therefore, states are expected to adopt the standard set by IHRL as much as possible in all constitutional and legislative measures covering education within their domestic jurisdictions.

Nigeria regained political independence in 1960. Before this, there were a series of constitutional changes and amendments during the colonial period, which focused mainly on increasing the representation of regions in the government and other emergent political needs.Footnote 30 For instance, the Constitution was amended in 1922 (Clifford’s Constitution), 1946 (Richard’s Constitution), 1951 (Macpherson’s Constitution) and 1954 (Lyttleton’s Constitution). None of these colonial Constitutions made provisions for either human rights in general or the right to education; however, in 1960, civil and political rights were included for the first time in Nigeria’s independence Constitution to guarantee that minorities were incorporated into government affairs without discrimination.Footnote 31 This 1960 Constitution had no provisions on education.

As discussed above, in 1979, educational matters were included for the first time in the ConstitutionFootnote 32 under part II as FODPSP.Footnote 33 Arguably, the inclusion of education under the FODPSP was only meant to be a policy objective tied to the political will of the government in power, and not to confer any entitlement to individuals, ie an enforceable claim or right, which entitlement is the standard under IHRL. These provisions were repeated simpliciter in the current 1999 Constitution, thus both provisions are in pari materia. Under the Constitution, the FODPSP spans sections 13 to 24 and provides for educational objectives under section 18.Footnote 34

Section 18 demonstrates that the Constitution drafters have been influenced by dominant economic principles of human capital theory (HCT) that prioritize a focus on science and technology, and, also, could not recognize human dignity despite its significance and relationship with education. According to the report of the CDC, the “educational objectives” are expected to guide educational policy design and execution. A cursory analysis of the above constitutional provisions arguably demonstrates that they lack the nature of human rights that create entitlements in favour of individuals as is the case in IHRL. For instance, article 13(1) of the ICESCR provides that “the States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to education”, yet the word “right” was not used in Nigeria’s Constitution. As such, while there is no intention to make education a constitutionally codified human right, there is no provision on what education delivery will focus on achieving, which is the standard under IHRL.

Arguably, the inclusion of a purpose education will focus on achieving in the 1999 Constitution would have helped promote the significance of education and the need for everyone to have access to schooling since Nigeria became an E-9 country in 1993, which entails that it has substantial challenges in access to education. Therefore, not recognizing an identifiable purpose means that education delivery in Nigeria and the policies that control it could be influenced by several factors not compatible with the need for each individual to achieve human dignity.Footnote 35

Similarly, it is argued that the nature of the provisions in the 1999 Constitution could affect the contents of the provisions in the legislative mechanisms that control education in Nigeria based on constitutional supremacy, as contained under section 1(3) of the 1999 Constitution. Also, Nigeria practices constitutional dualism, which is recognized under section 12(1) of the 1999 Constitution. It provides as follows: “[n]o treaty between the Federation and any other country shall have the force of law except to the extent to which any such treaty has been enacted into law by the National Assembly”. In dualist states, international human rights treaties are not directly applicable to domestic jurisdictions. This provision clearly demonstrates that all treaties which Nigeria has ratified as a state party cannot directly apply until their enactment into municipal law by the National Assembly. For example, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the ACHPR) became applicable in Nigeria in 1983 when it was enacted into domestic law to become the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Ratification and Enforcement) Act (the African Charter Act). The status of the ACHPR in the hierarchy of laws in Nigeria was determined in the case of General Sani Abacha & 3 others v Chief Gani Fawehinmi by the Supreme Court.Footnote 36 The respondent (Gani Fawehinmi) commenced the suit before a Federal High Court and got judgment in his favour; however, the appellant was dissatisfied and appealed to the Supreme Court as the highest appellate court. The respondent relied on provisions of articles 4, 5, 6, 7 and 12 of the African Charter Act to seek remedies from the court. In its judgment, the Supreme Court, while recognizing that the African Charter Act is a statute with “international flavour”, held that the Constitution is superior to the ACHPR in the hierarchy. This means that the domesticated ACHPR merely has the status of domestic legislation and is therefore subject to the overriding provisions of the 1999 Constitution of Nigeria. Nevertheless, the obligation to provide access to education is ubiquitously on the government in Nigeria as a state party to major treaties that provide for the right to education. In what follows, I will discuss Nigeria’s obligation under IHRL and demonstrate that it is Nigeria’s responsibility to adopt appropriate measures to promote access to education that recognizes the human rights purpose of education.

Nigeria’s treaty obligations in education and E-9 countries’ membership

Here it is argued that, despite Nigeria’s E-9 status, following the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (Vienna Convention), it is Nigeria’s responsibility under IHRL to provide access to compulsory schooling for all children and to design education in a manner that focuses on the pursuit and achievement of human dignity as the human rights purpose. It equally argues that Nigeria’s vast population of children and its membership of the E-9 countries makes this obligation tighter and also indicates that Nigeria has not fared well in its human rights obligation to provide universal access to education.Footnote 37 As such, Nigeria is responsible for ensuring that every child has access to education that focuses on achieving the human rights purpose of education instead of just a vocational education that prepares learners for the labour market by instilling requisite skills and knowledge in them.

This section progresses in three stages. The first argues Nigeria’s responsibility to provide access to education under IHRL. The second section provides a broader picture of the challenges of education in states through the discussion of the formation of the E-9 countries under the supervision of UNESCO as a follow-up to the need to achieve the goals of education for all (EFA), argues what it means for access to schooling and identifies Nigeria as a member of the E-9 countries. Finally, it discusses Nigeria as an E-9 member and endeavours to provide a contextual illustration of the challenges of access to schooling.

Nigeria’s responsibility in education under IHRL

It is argued here that, despite Nigeria’s ratification of the ICESCR in 1993 as part of the demonstration of its commitment to the E-9 Declaration 1993 for the achievement of increased access to education, and the persistent challenge of low access to schooling, it is Nigeria’s responsibility under IHRL to adopt a proactive approach that promotes universal access with a further duty to adopt a broad approach in education design as an important factor for the achievement of human rights purpose. It then argues that a key weakness of this obligation is Nigeria’s discretion to adopt appropriate measures, which could promote an economic purpose that serves the development interest of the state. Treaty ratification requires Nigeria to take steps to comply with the obligation it imposes under article 26 of the Vienna Convention. For instance, Nigeria ratified the ICESCR on 29 July 1993, the UNCRC on 19 April 1991 and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights on 29 July 1993.

Article 2(1) of the ICESCR, in combination with article 2(1) of the UNCRC, is the basis of the obligation on Nigeria to ensure compliance with its international human rights responsibilities having ratified the treaties. As a follow-up, the Vienna Convention under article 26, which supports the international law principle of pacta sunt servanda, requires Nigeria to abide by its human rights obligations. Article 26 of the Vienna Convention provides “[e]very treaty in force is binding upon the parties to it and must be performed by them in good faith”.

The Vienna Convention governs the interpretation of treaties under IHRL and it requires Nigeria to abide by its treaty responsibilities. Nigeria equally ratified other treaties that impose an obligation to realize education as a human right per its human rights purpose as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview table showing treaties on the right to compulsory education Nigeria has ratified

In education, Nigeria’s obligation is to guarantee each child universal access to compulsory education in accordance with the provisions of article 13(1) of the ICESCR.Footnote 45 This is more important considering the recognition of the inherent dignity of all human beings under article 1 of the UDHR and the significance of education in promoting human dignity. As a result, this paper argues that states should design education delivery in a manner that recognizes the need to achieve human dignity. For Nigeria as an E-9 country, it is argued that domestic education delivery should be designed to promote the pursuit and achievement of human dignity; however, because of the nature of IHRL, states like Nigeria are at liberty to determine the trajectories of education delivery. As an E-9 country, Nigeria may have ignored its human rights responsibility to promote increased access to schooling, since the hallmark of the E-9 membership is the existence of adult illiteracy caused by persistent low access to learning and a high proportion of out-of-school children.

It is important to note that the acquisition of skills and knowledge and, in the case of children, basic literacy, numeracy, problem-solving and oral expression skills which the 1990 EFA Declaration emphasizes are important for each child’s full development, should however not be the focus of education delivery.Footnote 46 In accordance with the purpose of education under IHRL, it is important therefore that Nigeria adopts measures that offer access to a broad curriculum to all children. As will be recalled,Footnote 47 HCT requires a focus on specific subjects (STEM – sciences, technology, engineering and mathematics) that prepare each learner to properly fit into the labour market after school without needing additional pre-job training. However, consistent with the need to achieve the human rights purpose of education ie human dignity, there is a need to design education content to target the complete development of each learner and not just to inculcate certain vocational skills that have been adjudged necessary for the labour market. Nevertheless, whatever approach Nigeria adopts, it needs to take proactive steps to address the problems of illiteracy and limited access to schooling for children. In doing this Nigeria needs first to recognize it as its human rights obligation and then adopt the 4-A scheme (availability, accessibility, acceptability, adaptability).Footnote 48 Katarina Tomasevski as the first UN special rapporteur on the right to education, in response to persistent problems of education delivery amongst states of the UN, especially the challenge of low access to schooling in 1999, formulated the 4-A scheme as a helpful guide in states’ performance of their human rights obligations in education.Footnote 49

The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) recommend that “education in all its forms and at all levels shall exhibit the … interrelated and essential features” of the 4-A scheme.Footnote 50 This article will not discuss the 4-A scheme separately but argues that the 4-A scheme could help address some of the problems of domestic education delivery and its complexity, especially in Nigeria and other E-9 countries. In what follows, the article will discuss the E-9 countries and argue the existence of problems of access to education that has given rise to illiteracy, especially among women and girls as a common denominator, epistemically leading to educational inequalities from the standpoint of the capabilities approach.Footnote 51

E-9 countries and access to education challenge

This section endeavours to provide a wider picture of education challenges using the E-9 countries, describing how the worsening problems of access to schooling globally, especially amongst the less developed countries of the South, underscored the formation of E-9 countries under UNESCO in 1993. It argues that their core common characteristic is a challenge of access to schooling and the prevalence of illiteracy among women and girls. It equally contends that a striking feature of most of the E-9 countries is the lack of a provision on the purpose of education as a core ingredient that brings to the fore the significance of access to schooling in the quest to achieve human dignity and the dangers children without access to education are exposed to. However, Bangladesh, Brazil and China have nuanced provisions on education and its purpose which is considered economic purpose-driven. A core objective of IHRL in making education a human right is to promote equal access to schooling and reduce all forms of inequalities in school enrolment. As a result, under IHRL, it is the responsibility of states to guarantee every child within its territorial sovereignty equal access to schooling and ensure it focuses on the full personality development of each person. However, the failure of states to comply with their human rights obligation means that there will be a lack of universal access to schooling leading to adult illiteracy as a common denominator to countries grouped under the E-9, though in varying degrees.Footnote 52

After the 1990 World Conference on EFA at Jomtien, which targeted the improvement of access to learning, especially for children within the basic education age, UNESCO supported another initiative meant to promote another round of commitment amongst select states to encourage increased access to learning, particularly within the most populous but poor (low-income) countries. This led to the designation of E-9 member countries in 1993 under the supervision of UNESCO in New Delhi, India, during a summit of the heads of state of the nine most populous developing countries with the highest number of out-of-school children and illiterate adults, to further strengthen the 1990 EFA Declaration. UNESCO is the secretariat of the E-9 initiative and encourages a collaborative partnership amongst members to address existing challenges in education and future emergent educational problems. The “E” means education and the “9” represents the nine member countries, which are (in alphabetical order) Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria and Pakistan.Footnote 53 The E-9 countries are home to over half of the world’s population, two-thirds of the world’s illiterate youth and adults and almost one-half of the world’s out-of-school children and they have similar challenges, however, their dissimilarities have widened since 1993.Footnote 54 Some of the basic education challenges common to E-9 countries are “overburdened classrooms, a lack of trained teachers and high rates of out-of-school children” and members like Nigeria have been working on addressing the low rate of enrolments and the high number of out-of-school children from 1993 to date. The partnership of members focuses on pooling ideas together to tackle these problems that directly affect access to schooling.

Notably, a common denominator in E-9 countries is lower access of girls to universal schooling than boys, and this applies significantly to Nigeria – despite the epistemic truism according to the World Bank that projects girls education as “the highest return investment available in the developing world”.Footnote 55 According to UNESCO Institute of Statistics, “32% of girls in Pakistan between the ages of 6 and 11 years old are out of school compared to 21% of boys; and in Nigeria, 40% of girls are not in school compared to 29% of boys”. In a country like India, “40% of youth are out of school at the upper secondary level” and in Pakistan “nearly 70% of adolescent girls are not enrolled in upper secondary education compared to 60% of boys”.Footnote 56

From 5–7 February 2017, representatives of the E-9 countries gathered in Dhaka for the E-9 Ministerial Meeting with the UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova and the Prime Minister of Bangladesh Sheikh Hasina in attendance, to renew their commitment to addressing the challenges of universal access to education in each country and decide on a tenable approach to the realization of the Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) – Education 2030 Agenda – recognizing that the SDGs adopt a more expanded strategy to education when compared with the Millenium Development Goals.Footnote 57 This meeting, which led to the adoption of the “Dhaka Declaration”, focused on providing opportunities for states to exploit the leverage provided by EFA to forge a common ground to address the goals of SDG4 through “education legislation, policy, planning, financing, management, coordination and monitoring” and to drive increased access to schooling in member states of the E-9.Footnote 58 At the meeting, the nine member countries were encouraged to expand cooperation in subject areas such as “out-of-school children, early childhood care and education, information and communication technology in education, joint monitoring of progress towards SDG4 targets and commitments, joint advocacy and work to increase government funding for education”.Footnote 59

UNESCO recognizes that the achievement of the global education agenda may not be met if there is no progress in access to education and literacy levels in the E-9 countries. As a result, the E-9 countries have been incorporated into the Global Alliance for Literacy (GAL), which is an alliance within the Framework of Lifelong Learning that advocates the significance of youth and adult literacy. However, according to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, there has been a steady decline in the rate of out-of-school children in the E-9 countries, but this has been much slower in Nigeria and Pakistan as a result of higher numbers of children that require access to schooling and the existence of abject poverty.Footnote 60 Thus, there seems to be no doubt about the existence of challenges to access to education in Nigeria as an E-9 country, and this raises questions about the performance of its human rights obligations to provide free universal compulsory education, having ratified major treaties that provide for universal access to education for all children. In what follows, Nigeria as an E-9 country and the problems of access to schooling are examined to give a contextual picture of education problems and how they determine the level of access to learning.

Nigeria’s problem of access to education as an E-9 country

This subsection uses Nigeria as an E-9 member to demonstrate a contextual picture of problems of access to education that is a notable characteristic of E-9 countries, arguing that it has historical antecedents in Nigeria and justifies its membership of the E-9 countries, which brings into question Nigeria’s compliance with its obligation to provide universal access to education under IHRL. It argues that while low access to education is a common denominator amongst E-9 countries, it is more severe in some states than others, especially in Nigeria for contextual reasons. This article recognizes that access to education is an essential precondition for the achievement of not only human dignity as the human rights purpose but also for Nigeria’s economic development and ability to cater for the welfare of its citizens. It argues that while low access to schooling is a significant challenge in education in Nigeria and has remained a critical element and defining characteristic, there are also other problems in education.Footnote 61 These underlying problems result in persisting low access. Where necessary, this subsection will utilize statistical information to illustrate the challenges to access to schooling and illiteracy in girls and women.

In the case of Nigeria, the problem of access to schooling started from the time the missionary societies introduced formal education in 1842 as discussed above.Footnote 62 When Nigeria was divided into three regions in 1951, instead of harmonizing access to schooling through each region independently funding the delivery of education appropriate to the region, the disparity in access to schooling only increased which to a large extent increased the number of illiterates and the absolute number of children without access to education. In 1972, after analysing the magnitude of enrolment disparities in compulsory schooling, the then federal commissioner of education put the primary education enrolment ratio between the northern and the southern regions at 1:4.Footnote 63 He said: “for every child in a primary school in the Northern States there are four in the Southern States; for every boy or girl in a Secondary School in the North, there are five in the South”.Footnote 64

The above demonstrates the existence of historical antecedents of problems of access to schooling in Nigeria affecting regions, states and genders and justifies Nigeria’s classification as an E-9 country. The introduction of UPE in 1976 and the subsequent launch of UBE in 1999 have not addressed these problems of access to schooling in Nigeria. Despite the introduction of free UBE in Nigeria, through the UBE scheme, in response not only to Nigeria’s obligation under IHRL but also to its commitments under the 1993 E-9 Declaration as an E-9 member, the problem of low access to education persists. It is important to note that Nigeria’s institutional efforts targeted at addressing the problem of access to schooling as a qualifying factor to becoming a member of the E-9 countries have arguably yielded little or no success because, to date, Nigeria is still a member of the E-9 countries.

According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, the total (male and female) literacy rate among the population of Nigeria aged 15–24 years in 2008 was 66.38 per cent.Footnote 66 The primary education completion rate in 2010 was 73.763 per cent, for female pupils 68.91 per cent and for male pupils 78.449 per cent.Footnote 67 According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2010, about three million children between the ages of 6–14 years old had never been to school, ie 8.1 per cent of the child population from 6–14 years old, and about one million dropped out of school, ie 3.2 per cent of children aged 6–14 years old.Footnote 68

Similarly, according to the “Millennium Development Goals performance tracking survey 2014 report”, the literacy level in women between the ages of 15–24 (young women) in 2012 was 66 per cent and 66.7 per cent in 2014, which validates Nigeria’s membership of the E-9 countries. Table 3 shows the level of literacy amongst women aged 15 to 24 in 11 Nigerian states selected out of 36.

Table 3. Literacy level of young women aged 15–24 (adapted from “The Millennium Development Goals performance tracking survey 2014 report” published by the National Bureau of Statistics)Footnote 65

Table 3 illustrates high levels of illiteracy amongst women aged 15–24 in the northern Nigeria states of Sokoto, Bauchi and Yobe. The data above arguably shows that the UBE policy introduced by the government in Nigeria in 1999 and other programmes of action Nigeria has adopted have not yielded the desired results since illiteracy amongst young women in the northern Nigeria states of Sokoto, Bauchi, Yobe, etc remains worrying. A predictable twist to the problem of access to education amongst women and girls is the impact of the lack of literacy skills for mothers on their children’s learning given that they are unable to support their children’s schoolwork.Footnote 69 This tends to scrutinize the negative transferability of the broad dynamics of illiteracy in women. This article will not pick up this leg of argument.

The data above endeavours to substantiate the existence of challenges of access to schooling in Nigeria that formed the basis for its inclusion as an E-9 country. However, it does not foreclose the existence of other problems in education in Nigeria as a multicultural and young democratic country which this article will highlight that have perennially been sustaining low access to schooling. For instance, in Nigeria, educational problems are multifaceted and start with insufficient constitutional, legal and policy mechanisms to guarantee smooth education delivery and the lack of purpose as an important element that provides impetus. Similarly, the lack of security for pupils and staff and the destruction of schools in conflict ravaged areas like the North have exacerbated the problem of access to education in Nigeria. For example, the number of attacks on schools in Nigeria and five other African countries (Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, Cameroon and Central African Republic) increased from 303 in 2019 to 802 in 2020.Footnote 70 About 5,000 schools were shut in Western Africa in 2021.Footnote 71 Notably, despite these challenges in education, Nigeria’s responsibility, as argued above, requires that it takes all appropriate steps to ensure smooth education delivery. This includes Nigeria’s obligation to adopt legislative measures. Thus, in what follows, the legal mechanisms that govern education delivery in Nigeria, which represent the legislative measures Nigeria adopted in obedience to the requirements of IHRL, are discussed.

Domestic legislative measures in education lack explicit provisions on the purpose of education

While the analysis above focuses on the purpose of education and the relevance of the legal mechanisms in addressing the problems of access to schooling, this section argues that these legal mechanisms fell short of IHRL standards by not explicitly providing for the purpose education will seek to achieve. It argues that for Nigeria, as an E-9 country, to tackle the problem of access to schooling and illiteracy, it needs to underscore the significance of access to schooling by recognizing that human dignity accentuates the importance of access to education.

This part argues that the legislative measures Nigeria adopted in compliance with its human rights obligations are insufficient and have not helped promote increased access to schooling as an E-9 country with challenges to access to education. It is Nigeria’s human rights obligation under article 2(1) of the ICESCR to adopt appropriate legal mechanisms that will stimulate the achievement of the human rights purpose – human dignity. This may require legislative measures to identify the purpose of education and set out proactive legal and policy steps to realize it. This is in recognition of the significance of physical access to schooling and the pursuit of human dignity, which cannot be achieved without access to education, essentially underscoring the nexus between access to education and the achievement of human dignity. In what follows, three legislative enactments will be substantially discussed.

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Ratification and Enforcement) Act 2004: Education has no clear purpose

This subsection focuses on the African Charter Act and argues that it has not helped tackle the challenges of access to education in Nigeria because it could not provide a specific purpose for education, which is important as it brings to attention the significance of education and serves as a reminder to the dangers of not having access to education. It also argues that the African Charter Act does not comply with the normative standards in treaties like the ICESCR and the UNCRC, which contain core elements that underscore the centrality of human dignity in education delivery. Incorporating the African Charter Act into municipal law follows section 12(1) of the 1999 Constitution of Nigeria; however, it ignored the recognition of the purpose of education and could be regarded as a mere constitutional formality.Footnote 72

The analysis of the African Charter Act will focus exclusively on article 17 because it is the only article that provides for the right to education.Footnote 73 Therefore, based on an interpretative and contextual critique of article 17 of the African Charter Act, with reference to the purpose of education regarding the standard provisions of article 13(1) of the ICESCR, this paper attempts to demonstrate that article 17 could not provide a clear purpose education will achieve and in doing so could not recognize human dignity as the human right purpose of education. Firstly, it argues the implication of not providing for the purpose of education by the provisions of article 17 of the African Charter Act, and secondly, that the provisions of article 17 do not conform with IHRL as a normative standard.

Article 1 of the ACHPR requires member states to take statutory measures to give effect to the human rights provided under the ACHPR.Footnote 74 In compliance with article 1 of the ACHPR and section 12(1) of the 1999 Constitution discussed above, Nigeria incorporated the ACHPR into its national laws in 1983 as the African Charter Act during the democratic administration of Shehu Shagari.Footnote 75 While the African Charter Act maintained the style of the ACHPR, apart from contextual features like Nigeria’s coat of arms, short and long titles, recitals and other implied statutory contents, it is argued that the African Charter Act ignored the purpose of education and of course human dignity as the human right purpose, which is the standard under IHRL. Although the African Charter Act has three parts and 68 articles, only article 17 provides for the right to education, but without a purpose.

Thus, article 17 of the African Charter Act is a verbatim duplication of the provisions of the ACHPR. As such, the shortcomings analytically identified in article 17 of the African Charter Act apply to the ACHPR. This means that the African Charter Act ignored the purpose of education, especially human dignity, as the human right purpose, which is a vehicle that should drive domestic education delivery. As a result, it is argued that the provisions of article 17 of the African Charter Act may not be helpful in the pursuit and achievement of human dignity as it has no clear purpose.

It is argued that article 17(1) of the African Charter Act is prima facie deficient in detail for not providing the purpose of education.Footnote 76 In addition to drafting flaws identified in article 17, the African Charter Act generally has recognisable legal impediments that limit its applicability and justiciability, particularly for the second generation of human rights it provides, eg the rights to education, health, etc. This is because, in Nigeria, the Constitution is regarded as supreme, and any other law could be nullified through judicial interpretation if found inconsistent with the Constitution. It should be noted that article 17 was the basis of the case in Socio-Economic Rights Accountability Project (SERAP) v The Federal Republic of Nigeria and the Universal Basic Education Commission Footnote 77 before the Economic Community of West African States Community Court of Justice in 2009. The arguments in this case that put forward the supremacy of Nigeria’s Constitution over any other law could constitute a constitutional impediment to achieving the human rights purpose of education, where it has been statutorily recognized.

Secondly, using article 13 of the ICESCR as a reference text, it is argued that article 17 of the African Charter Act could not provide for the purpose education delivery will focus on achieving, and therefore, its provision is at variance with the standard provisions of IHRL. In IHRL, provisions on the right to education are always accompanied by their purpose and delivery focus. Article 13(1) of the ICESCR partly provides: “The States Parties … agree that education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity and shall strengthen the respect for human rights”.

The CESCR, in emphasizing the importance and need to ensure the purposes education seeks to achieve are incorporated into statutory provisions and achieved through robust legal and educational policy mechanisms in paragraph 49 of General Comment No 13 (1999), suggest that “[s]tates parties are required to ensure that curricula, for all levels of the educational system, are directed to the objectives identified in article 13(1)”.Footnote 78 The drafters of the UDHR, as the travaux preparatoires reveal, insisted on inserting a purpose for education delivery to ensure the focus on an objective purpose that does not depart from the basic intention of making education a human right – ie promoting everyone’s ability to lead a life with dignity. However, the drafters of the ACHPR did not emulate and adopt the style of the provisions for the right to education under article 13(1) of the ICESCR as a standard of achievement for all peoples, states and nations to follow. Arguably, the drafters may have ignored the purpose of education because of either the discretion allowed states under IHRL or the influence of neo-liberal and neoclassical economic ideals that have steadily diffused globally at this time, including in Nigeria.

In sum, it is argued that the provisions of the African Charter Act, and the identical provisions of the ACHPR, could neither provide for the purpose of education nor recognize human dignity as the human rights purpose of education having regard to the raison d’être for including the purpose of education as debated during the deliberations heralding the drafting of the UDHR.Footnote 79 While adopting the ACHPR, Nigeria missed the opportunity to vary article 17 to provide for the purpose of education, which would have aligned with the requirements of article 13(1) of the ICESCR. Overall, as an E-9 country, article 17 of the African Charter Act has not made any identifiable impact in either enhancing access to education or achieving literacy and human dignity.

The Child’s Rights Act 2003 omitted the purpose of education

This subsection argues that the Child’s Rights Act 2003 (CRA), which provides for the right to education and is part of the domestic legislative measures Nigeria adopted in compliance with its obligations under the UNCRC and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child 1990 (ACRWC), ignored the purpose of education. As a result, it argues that the CRA may not help address the challenge of access to education taking cognisance of its non-recognition of human dignity as a central element in education. This is because recognizing human dignity through an explicit provision on the purpose of education could help address the problems of access to schooling as an E-9 country and be the driving force controlling domestic education delivery. It then argues that the CRA is thought to have provisions that seem to have cultural implications for the predominantly Muslim North. Thus, the CRA appears to have two acceptance levels in the 36 states of Nigeria and the federal capital territory (FCT).Footnote 80 While states of the South accept the CRA but have not fully implemented it, probably because of unwanted responsibilities connected to it, the northern states ignore it because of certain provisions that may conflict with some established cultural practices, such as marrying a girl less than 18 years old.

These issues are argued in two stages. Since only section 15 of the CRA makes provisions for the right to compulsory education, the first part focuses on that and aims to systematically analyse it vis-à-vis the provisions of IHRL and argues that, while the CRA makes specific provisions regarding compulsory education of children, it ignores the purpose education will seek to achieve. The second endeavours to show that the CRA arose in compliance with obligations under the UNCRC and ACRWC, and equally traces its legislative history, highlighting the controversies that eventually watered down its ability to have a purpose that will drive compulsory education delivery.

The CRA has 24 parts and 278 sections, therefore, it is a lengthy piece of legislation, longer than the UNCRC and the ACRWC. Section 277 of the CRA which is in pari materia with article 1 of the UNCRC defines a child as a person who is not yet 18 years old. Section 15 of the CRA provides “[e]very child has the right to free, compulsory and universal basic education and it shall be the duty of the government in Nigeria to provide such education”. This means that in Nigeria, every individual not yet 18 years old is entitled to all the rights, privileges and protections that the CRA provides. This was the first domestic enactment to make direct provisions for the right to compulsory education of children in Nigeria. However, while its provisions appear to have the characteristics of the normative language and nature of human rights as evident in IHRL, it ignored the purpose of education. Section 15, instead of providing for the purpose of education as is the common standard under IHRL (for instance, article 13 of the ICESCR), merely imposed the obligation to provide universal compulsory education on the government without any provision on the purpose of education to guide educational policymaking. Under IHRL, all treaties that provide for the right to education consistently provide for the purpose of education to ensure that education delivery serves a universal purpose, despite contextual variations. It is argued that while the drafters of section 15(1) of the CRA intended to create a right to education because the corresponding duty has been imposed on the Nigerian government, it ignored the purpose education will focus on achieving. Rights correlatively give rise to obligations on another party.Footnote 81 Therefore, specifically imposing the duty to provide compulsory schooling on the government under section 15(1) of the CRA is arguably superfluous because it is customary in international law that the obligation to provide education to all children in a state is on that government as inter alia sovereignty its responsibility.Footnote 82

The implication of section 15(2) of the CRA is that the responsibility of ensuring that children enrol in compulsory education is on parents. It equally requires them to guarantee continuity and compulsory education completion, ie six years of primary schooling and three years of junior secondary education. It is important to note that because of the use of the word “shall”, the obligation of each parent or guardian under this section seems mandatory.Footnote 83 This means all parents should enrol their children in the government’s compulsory education. However, section 15(2) of the CRA does not recognize the choice of parents and children when they have the capacity, ie it does not acknowledge the right of parents to choose the type of school their children will attend nor guarantee the curriculum is in accord with the moral convictions of parents as recognized under IHRL, especially since education has no recognized purpose. It is argued that this is a significant lacuna considering the existence of a compulsory obligation on parents under section 15(2) of the CRA, particularly in a multicultural society like Nigeria.

Section 15(3) of the CRA requires parents to endeavour to guarantee the transition of children from compulsory schooling to the next stage, ie senior secondary education. Section 15(4) of the CRA gives parents the option to either ensure children continue their educational career at the senior secondary education level or encourage them “to learn an appropriate trade”.Footnote 84 It is argued that this provision has a significant import, particularly within the southern states of Nigeria, where the enrolment of girls is slightly higher than boys in compulsory schooling. It is part of the culture of people within the South region for boys who could not continue schooling to learn a trade. So, with the provision of section 15(3) of the CRA, this practice may have gained legal significance. In sum, putting the provisions of section 15 of the CRA side by side with the provisions of article 13(1) of the ICESCR and article 29(1) of the UNCRC arguably shows that the provisions of section 15 of the CRA do not provide any purpose of education, which would have been necessary to drive the trajectories of education delivery.

Secondly, as may be recalled from the arguments above, article 4 of the UNCRC requires states to take appropriate legislative measures to give effect to the rights recognized under the convention. It provides that “States Parties shall undertake all appropriate legislative, administrative, and other measures for the implementation of the rights recognized in the present Convention”. Similarly, Nigeria has treaty responsibilities under article 1(1) of the ACRWC and is expected to take appropriate statutory steps to give effect to the ACHPR.

Therefore, this paper argues that since the Child’s Rights Bill was presented to Nigeria’s National Assembly for parliamentary processes in the early 1990s when Nigeria became an E-9 country, and the UNCRC and ACRWC predate the CRA, it was probably drafted in compliance with the treaty obligations arising from them and the need for Nigeria to take proactive measures to promote increased access to schooling as an E-9 country.Footnote 85 It is important to note that while the ACRWC adopted the provisions of the UNCRC, the CRA does not refer to either the UNCRC or the ACRWC. However, the provisions of the UNCRC, the ACRWC and the CRA are similar in some respects, particularly since they have made provisions focusing only on children.

The Child’s Rights Bill stirred debates at the National Assembly during legislative proceedings because certain sections were deemed contentious, considering Nigerian society’s multicultural nature.Footnote 86 It is argued that the legislative dialectics overshadowed the need for section 15 of the Bill to provide for the purpose of education as a vector for education delivery. While accounts of the legislative history of the Bill at the National Assembly are somewhat disjointed, according to Akinwumi, several attempts were made to complete the legislative procedures with opposition anchoring on perceived religious and cultural concerns.Footnote 87 After up to ten years of legislative deliberations, the National Assembly relied on section 299(a) of the 1999 Constitution (which authorizes the National Assembly to make laws for the FCT) to pass the Child’s Rights Bill for the FCT only because of unending legislative controversies. In July 2003 the Bill passed its final law-making procedures, and in September 2003, the President of Nigeria signed it into law as the CRA.Footnote 88 The National Assembly made the CRA open to all 36 states to adopt it in their various states.Footnote 89

Despite the commendable provisions of the CRA, it became one of the most contested bills ever before the National Assembly. For instance, section 21 prohibits child marriage, section 22 outlaws betrothing a child, section 24 proscribes tattooing a child, section 27 disallows removing children from their parents and section 30(2)(a) bans using children to beg for alms. Some of these provisions are against certain accepted cultural and religious practices in some states in Nigeria, particularly in the northern region.Footnote 90 As a result, the refusal of some Nigerian states to adopt the CRA for fear of correlative commitments and other cultural concerns, particularly within the northern states, means that the provisions of section 15 may never be implemented in the states that have rejected its internal adoption. As an E-9 country, this arguably increases the number of out-of-school children across the states and largely points to the cultural divide between states of the South and North. For instance, within the northern states, children known as Almajiris, Footnote 91 may be seen begging on the streets given that they leave their parents to learn Arabic and recite the holy Quran, girls below the age of 18 can be given in marriage, etc. These are not accepted cultural practices in the southern states.

In sum, while section 15 of the CRA suffers from constitutional impediments and wants of the purpose education will seek to achieve, its provisions lack fundamental appurtenances that could support an education delivery that focuses on the pursuit and achievement of human dignity. Overall, the CRA could encourage more access to schooling if it provides for the purpose of education, and recognizes human dignity as central to education delivery, which could arguably promote its acceptance amongst the states of Nigeria.

The Universal Basic Education Act 2004 ignores the purpose of education

While the UBE Act 2004 is important for the achievement of the goals of the E-9 Declaration, which is meant to simultaneously pursue the realization of EFA goals and Nigeria’s obligation under IHRL, its section 2(1) neither provides for the purpose of education nor articulates education as a human right, both of which are necessary to underscore the significance of having access to learning. This is despite the sense of hope the UBE Act provided as an important instrument deemed essential for achieving the goals of EFA – universal access to compulsory schooling and achieving literacy. Therefore, this subsection argues that the UBE Act, especially section 2(1), is not in conformity with IHRL standards since it does not provide education as a human right, although the “marginal note” to section 2 used the phrase “right of a child to compulsory, free universal basic education”. The argument is built up through a critical analysis of section 2 of the UBE Act concerning the purpose education is designed to achieve vis-à-vis the provisions of IHRL, chiefly, article 13(1) of the ICESCR as a reference instrument.

It was launched on 30 September 1999 (before the third E-9 ministerial review meeting for EFA 2000 assessment at Recife, Brazil from 31 January to 2 February 2000) as a second attempt to harmonize compulsory school enrolments and bring uniformity to the fragmented compulsory education system. It was after the fifth ministerial meeting of the E-9 countries held in Cairo, Egypt from 19 to 21 December 2003, which marked the tenth anniversary of the formation of E-9 countries that the enabling law was completed, ie on 26 May 2004.Footnote 92 This meeting focused on children’s education and early childhood care and education while reviewing the policy objectives of EFA in E-9 countries and the results achieved so far. These are the areas of education covered by the UBE Act.

The UBE agenda reflects Nigeria’s expression of its commitment to the goals of EFA, the Delhi E-9 countries declaration of 1993 and a means to fight widespread poverty,Footnote 93 having been launched ahead of the Dakar framework of action and the MDGs.Footnote 94 Thus while EFA is an international initiative to increase access to compulsory school enrolments and literacy levels, the UBE agenda at its inception was a domestic version of EFA needed by Nigeria as an E-9 member country. That is Nigeria’s strategy to achieve EFA, and it incorporated the educational goals of the E-9 countries declarations, especially those agreed at the fifth ministerial meeting at Cairo, the Durban Statement of Commitment 1998, the MDGs and the OAU Decade of Education 1997–2006.

The UBE scope comprises six years of formal primary schooling, three years of junior secondary education and four years of senior secondary education.Footnote 95 Section 2 of the UBE Act covers compulsory education of children and has four subsections. While subsections (1)-(3) impose duties, subsection (4) deals with offences. Section 2(1) imposes the responsibility to provide free universal compulsory education on the government and section 2(2) imposes the duty on parents to ensure that children enrol in compulsory education. Therefore, parents are expected, in the educational interest of children, to ensure that each child enrols in compulsory education. To ensure that this important duty on parents is discharged, section 2(3) requires stakeholders in the education sector within each local government area to ensure that each parent complies with this obligation. Given the importance attached to compulsory education by the drafters of the UBE Act, and considering Nigeria’s membership of the E-9 countries, it is a criminal offence for any parent to ignore the duty of enrolling their children in school. This means that there is a profound obligation on parents. In addition to the duty imposed on parents under section 2(2) of the UBE Act, the provisions of section 4(1) further mandate parents to endeavour, in the best interests of children, to ensure each child receives full-time education that suits the child’s age, ability and aptitude, particularly through sustained regular school attendance.

In contrast, a cursory analysis of the provisions of section 2(1) of the UBE Act vis-à-vis the standard provisions of IHRL, eg article 13(1) of the ICESCR, manifestly suggests that the provisions of section 2(1) could not provide for the purpose of education and, as such, jettisoned IHRL benchmarks. This means that section 2(1) of the UBE Act ignored recognizing human dignity as the human rights purpose of education. Article 26 of the Vienna Convention requires states to fulfil ratified treaties in good faith. As such, drafting domestic provisions on the right to an education that explicitly provides for the purpose education will focus on achieving, which is consistent with IHRL standards, arguably indicates that the state may comply with its treaty obligations based on the principles of pacta sunt servanda.Footnote 96 It is argued that recognizing human dignity as the human rights purpose of education in an E-9 country like Nigeria would serve the purpose of emphasizing the significance of education and the need to acquire learning through sustained access to schooling and thereby promote increased access to education. However, deviating from the way the right to education under IHRL is structured when couching domestic legislative measures appears to be an indication that the state may have decided to derogate from its treaty responsibilities. While states have the flexibility to determine the structure of domestic statutes, this paper argues that substantially complying with the provisions of IHRL in domestic legislative measures is harmless to the state and may help heed to treaty obligations, especially in recognizing human dignity’s centrality in education delivery.

It is argued that since the marginal note to section 2 of the UBE Act states “the right of a child to compulsory, free universal basic education, etc” and section 2 itself does not provide education as a human right, it appears contradictory considering the actual intent of the lawmakers. Although section 2(1), the operative part, takes precedence over the marginal note, it does not provide education as a right. Arguably, the UBE Act would have been a more useful education enactment if it provided for the purpose of education as a way of recognizing human dignity as the human rights purpose of education and, most importantly, mainstreaming education as a human right. Taken together, this section attempted to critically examine the purpose of education in the African Charter Act, the CRA and the UBE Act in Nigeria as an E-9 country and argues that they ignored the purpose education will focus on achieving and as such could not recognize human dignity. As a result, these legal mechanisms and the constitutional provisions in education have not helped address the challenges of access to schooling and adult illiteracy in Nigeria as a member of the E-9 group.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article argues the existence of a nexus between access to education and the achievement of human dignity as the human rights purpose of education. Given that the problem of access to education is a key characteristic of E-9 countries, which from the perspective of the capabilities approach nurtures educational inequality, this article contends that Nigeria’s membership epistemically evidences the existence of substantial problems of access to education on the back of its obligation to provide access to education under IHRL. It argues that Nigeria’s membership in the E-9 countries seems to illustrate its failure to provide access to education in obedience to the requirements of IHRL. This article equally argues that the lack of an explicit purpose education will achieve in the constitutional and legal mechanisms that guide education delivery, which this article argues to be a critical element that should drive education delivery and promote the achievement of human dignity, appears to contribute to the challenges of access to schooling. The educational policy mechanisms must be designed to promote both access to education and the pursuit and achievement of human dignity as the human rights purpose of education.

Competing interests

None