Introduction

As both a human right and an essential element for economic growth and poverty reduction, gender equality remains a constant aspiration of virtually all commitments to achieve sustainable socioeconomic development and overall enhanced societal well-being. For example, the promotion of gender equality and empowerment of women was an explicit Millennium Development Goal and remains as such in Agenda 2030, with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 urging all United Nations Member States to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls by 2030. In September 2024, the UN further affirmed this commitment through Action 8 of the Pact for the Future, which emphasises the importance of meeting the SDGs’ gender equality targets (United Nations 2024,8). Notwithstanding this global focus, gender inequality remains deeply entrenched in many societies, which is consistently reflected in the labour market. Women’s overrepresentation in vulnerable employment is a critical aspect of this inequality. Obstacles to addressing this include the large number of women, 740 million, working in the informal economy worldwide. Moreover, nowhere does the informal economy play a greater role in women’s employment than in sub-Saharan Africa, where 90% of women, alongside 84% of men, are working in informal jobs (ILO 2023).

Among the array of precarious working conditions that characterise the informal economy is limited or no access to maternity protection (COSATU 2012; Richardson et al Reference Richardson, Dugarova, Higgins, Hirao, Karamperidou, Mokomane and Robila2020). A comprehensive understanding of maternity protection consists of a number of elements, including:

-

Protections against hazardous workplace conditions that could jeopardise the health of a pregnant worker;

-

Protections against employment discrimination based on pregnancy or maternal status;

-

Paid maternity leave, which provides time to recover from birth and protects against job and income loss;

-

Cash and medical benefits during maternity leave;

-

Workplace breastfeeding arrangements that allow for the continuation of breastfeeding after the leave period; and

-

Support with childcare.

These elements collectively are critical to maternal health and employment, household income security, and child health and well-being (Richardson et al Reference Richardson, Dugarova, Higgins, Hirao, Karamperidou, Mokomane and Robila2020; Mogapaesi Reference Mogapaesi2022; Pereira-Kotze et al Reference Pereira-Kotze, Malherbe, Faber, Doherty and Cooper2022). Maternity leave, in particular, has extensive socioeconomic and health benefits, though these benefits can only be fully realised if the leave is paid, rather than unpaid (Heymann et al Reference Heymann, Sprague and Nandi2017; Earle et al Reference Earle, Raub, Sprague and Heymann2023). This evidence shows that paid maternity leave essentially reduces the economic penalties of taking time off, avoids the need for women to choose between caring for their babies and keeping their jobs, and increases the likelihood of women returning to their jobs at the end of their maternity leaves, thus reducing the disparity between men and women returning to work (Schulte et al Reference Schulte, Durana, Stout and Moyer2017; UNWomen 2019). Overall, therefore, maternity leave and other aspects of maternity protection are key components of the transformative policies called for in the 2030 Agenda and are essential to the achievement of multiple SDGs, particularly SDG 1 (ending poverty), SDG 3 (reducing maternal and infant mortality), SDG 5 (achieving gender equality and empowering women), and SDG 8 (promoting inclusive growth and decent work).

Given the foregoing, it is a critical research and policy concern that maternity protection “remains a dream” for the majority of women working in the informal economy in sub-Saharan Africa, according to advocates (Akina Mama wa Afrika n.d.). As it emerged during a panel discussion held among East African stakeholders at the 63rd United Nations Commission on the Status of Women in 2019, “poorly planned breastfeeding breaks where mothers have to choose between travelling miles to nurse their babies, which most forfeit because of the distances involved, and having to report to work immediately after a miscarriage” are some of the maternity protection transgressions that are prevalent in many parts of the sub-region (Akina Mama wa Afrika n.d). Thus, in line with the aims of this Themed Collection, this paper seeks to advance a deeper understanding of some of the obstacles to gender equality in sub-Saharan Africa by illuminating structural factors that often hamper women’s attempts to access maternity protection. The paper focuses on the informal economy, the sub-region’s largest employer for women, and draws largely on qualitative data obtained from case studies conducted in 2022 in three countries—Mozambique, the United Republic of Tanzania (hereafter, Tanzania), and Togo.

The three countries were purposively selected for the study as they are among the few that offer legislative and policy provisions for maternity protection that should reach some or all workers in the informal economy. For example, Togo is one of a very small number of countries globally (The Philippines, Nepal, Burundi, and Zambia), where legislation explicitly extends maternity leave benefits available through social security to informal workers. Other countries cover the informal economy by addressing workers who often comprise the informal economy, such as self-employed, agricultural, part-time, and domestic workers. Mozambique and Togo are among the only three low-income countries (the other being Burundi) globally that guarantee paid maternity leave cash benefits to self-employed workers while Tanzania is among the 54 middle-income countries with these guarantees in place, globally (WORLD Policy Analysis Center 2022). The three countries are also among the only 13 sub-Saharan African countries with guarantees in place to extend maternity benefit coverage to self-employed workers.

The paper begins by examining existing legislative frameworks across sub-Saharan Africa that are relevant to maternity protection. We further examine whether countries’ maternity leave policies are explicitly inclusive of women in the informal economy. Alongside regional data, we provide a detailed analysis of the relevant legislation of the three countries selected for case studies.

The paper then presents evidence from in-depth qualitative research undertaken in Mozambique, Tanzania, and Togo regarding implementation of their maternity protection laws. Drawing on interviews and focus groups with nearly 200 participants across 11 regions in the three countries, this section highlights barriers to access, sources of information, and experiences navigating maternity protection systems across these three countries. This section builds on existing evidence showing how complex and cumbersome administrative procedures can discourage both employees and employers from registering with social protection schemes or for workers to claim the benefits for which they qualify (ILO 2021,13).

Finally, drawing on recurring themes from the interviews, this paper examines the extent to which trade union membership and the financing mechanism for maternity leave facilitate or hamper access to maternity protection entitlements. Trade unions can play an important role in expanding access to social protection by informal workers at a variety of stages, from ensuring that informal workers’ voices are included in the development and design of policies to ensuring all workers know about the benefits they are eligible for, once policies have been enacted (ILO 2022,1). In terms of financing of maternity protection, ILO Convention No. 183, cognisant of the potential discrimination in the labour market if employers have to directly pay the full costs of paid maternity leave through an employer liability model, stipulates that cash benefits during maternity leave should be provided through compulsory social insurance or public funds and that contributions must be based on the full number of employees, regardless of sex (World Health Organisation 2024). While the ILO does not provide specific recommendations on thresholds for contributions from employers, employees, and public funds, it has made clear that countries should consider the feasibility of employee contributions in designing leave to reach informal workers in low-income countries (ILO 2016). This section bridges the background on the three countries’ financing structures with insights and perceptions about financing from stakeholder interviews.

In examining both explicit legal protections and individuals’ experiences with maternity benefits, this paper makes an important contribution to the literature on the expansion of paid parental leave and other maternity protections in low- and lower-middle-income countries, and in particular, the structural factors that shape the feasibility of reaching the informal economy. It has been argued that a human rights-based approach to social protection requires grounding social protection systems in a strong legislative framework that not only looks at applicable statutes, constitutional provisions, and international instruments that apply to a sector, but also establishes rights holders’ entitlements, rights, obligations, and redress procedures in a clear and transparent way. Such a framework should also avoid arbitrary or discretionary selection of beneficiaries (Holmes and Lwanga-Natale Reference Holmes and Lwanga-Natale2012; UNSRID 2015). An institutional framework, on the other hand, clearly and transparently identifies duty bearers in charge of specific roles and responsibilities at different levels of government as well as among non-state actors from various sectors such as civil society, the private sector, and development partners (UNSRID 2015). In addition to being a demonstration of political will, a multisectoral institutional framework has the potential to draw on the strengths and varied approaches of different partners. In turn, this framework can lead to the effective elimination of implementation barriers, and increase the impact that one sector or partner might have had alone (Health Policy Project 2014) as well as benefiting rights holders overall through effective delivery of social protection benefits. This paper demonstrates how each approach has relevance and applicability in the case of paid maternity leave for informal workers.

Finally, this paper provides evidence about the extent to which countries are meeting their commitments to maternity protection under global instruments including the SDGs and ILO Convention 183. In particular, this paper’s exploration of legislative and institutional frameworks is directly in line with SDG Target 5.c, which calls for the adoption and strengthening of policies and legislation to promote gender equality, as well as Target 8.8, which calls for the protection of labour rights and promotion of secure working environments for all workers, including those in precarious employment.

Examining the extent of maternity protection coverage across sub-Saharan Africa

To understand how legislated maternity protection varies across sub-Saharan Africa, the WORLD Policy Analysis Center (WORLD) systematically examined each country’s labour and social protection policies and legislation related to the following key elements of maternity protection: paid maternity leave; cash and medical benefits; job protection (the presence of explicit legislation prohibiting discriminatory dismissal during maternity leave); breastfeeding breaks for women who have returned to work; and legislation explicitly prohibiting workplace discrimination on the basis of pregnancy. All labour and social protection legislation was reviewed by at least two analysts from a multidisciplinary, multi-lingual team and coded to capture the nature of informal economy coverage. Data on paid leave, job protection, and discrimination reflect legislation as of 2022.

Among the features of paid leave examined was its duration. The most recent and current global standard and legislative instrument on maternity protection is the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Maternity Protection Convention (No. 183, 2000) and its accompanying Maternity Protection Recommendation (No. 191, 2000), which together entitle women to maternity protection including 14 weeks of paid maternity leave paid at a minimum of two-thirds of the woman’s prior wages. The scope of coverage for this Convention is all employed women, irrespective of “occupation or type of undertaking, including women employed in atypical forms of dependent work, who often receive no protection” (ILO, no date). In other words, the Convention makes specific mention of women working in the informal economy.

Accordingly, we examine whether and what duration of paid leave is available to informal economy workers. For the purpose of this study, informal economy workers comprised: agricultural workers (waged employees on farms and plantations who do not own or rent the land on which they work but are employed by farmers, companies, or agricultural contractors; domestic workers (those who performed work in or for a household or households within an employment relationship); part-time workers (those whose normal hours of work are less than those of comparable full-time workers); and the self-employed. We separately looked at each of these categories of workers because they are often treated differently in legislation, underscoring variation in leave access by women in different types of informal jobs.

Three countries were then selected as case studies, based on the strength of their legislative approaches to addressing the informal economy. We present details on these approaches alongside the regional policy data.

Findings: legislative frameworks

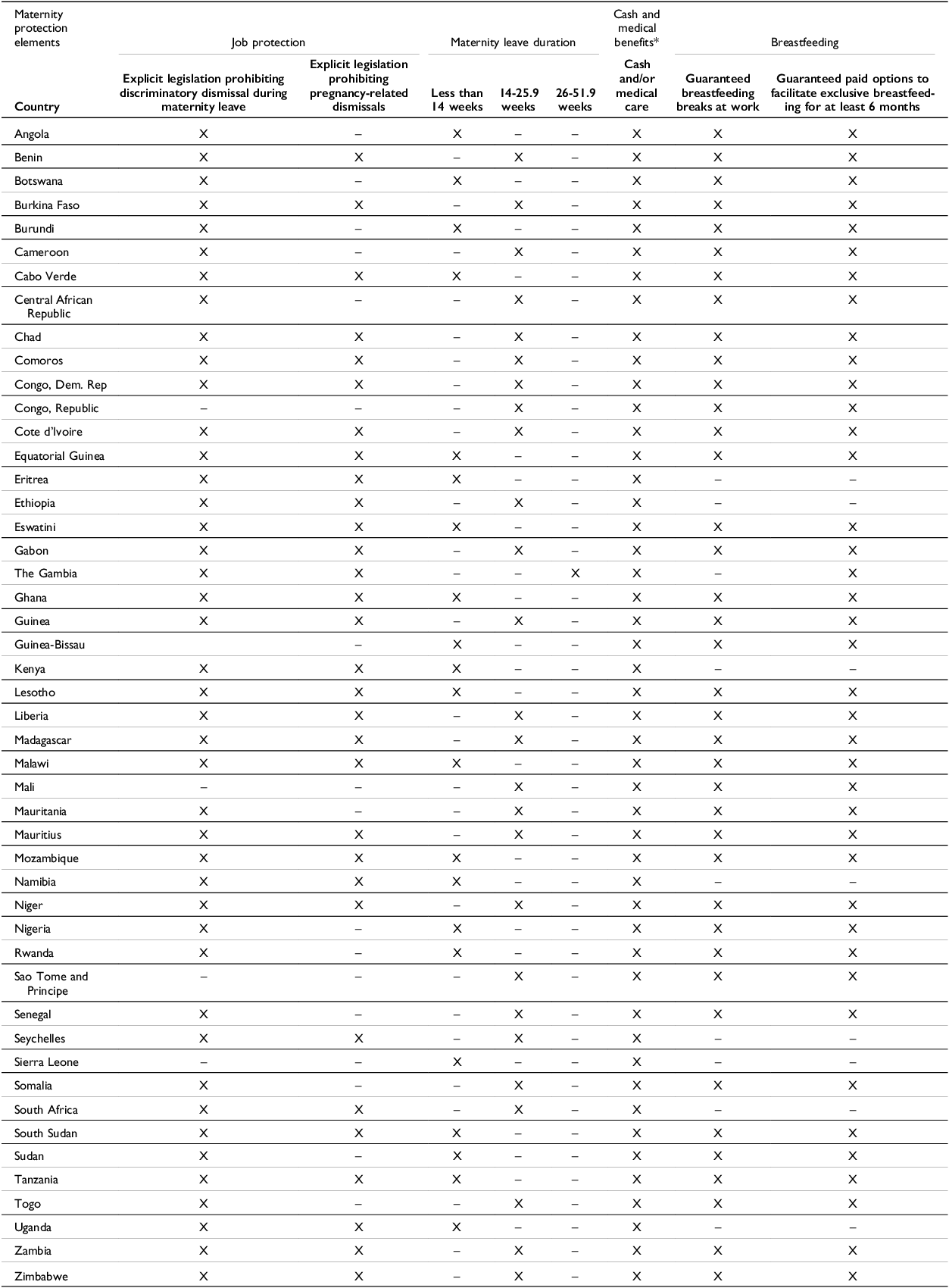

Although only five countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, and Senegal) have ratified the ILO Maternity Protection Convention (No. 183, 2000), many countries in the region have enacted laws and policies advancing some of its key provisions. As of 2022, all sub-Saharan African countries make provisions for paid maternity leave, with the majority of the countries providing at least 14 weeks prescribed by the Convention (Table 1). By the same token, all countries in sub-Saharan Africa provide either one or both of cash and medical benefits; only five do not have explicit legislative prohibitions of discriminatory dismissal during paid maternity leave (job protection); and there is widespread enactment of explicit legislation prohibiting pregnancy-related dismissal with only 17 of the 48 countries analysed having no such legislation. Table 1 further shows that it is only in eight countries that women have no guaranteed entitlement to either at least six months’ paid maternal leave or paid breastfeeding breaks at work, the minimum required to support the six months of exclusive breastfeeding recommended by the World Health Organisation.

Table 1. Presence of selected maternity protection elements, sub-Saharan Africa, January 2022

Source: Elaborated from data available at WORLD Policy Analysis Center (2022), except * which was derived from the ISSA Country profiles—Africa (2024).

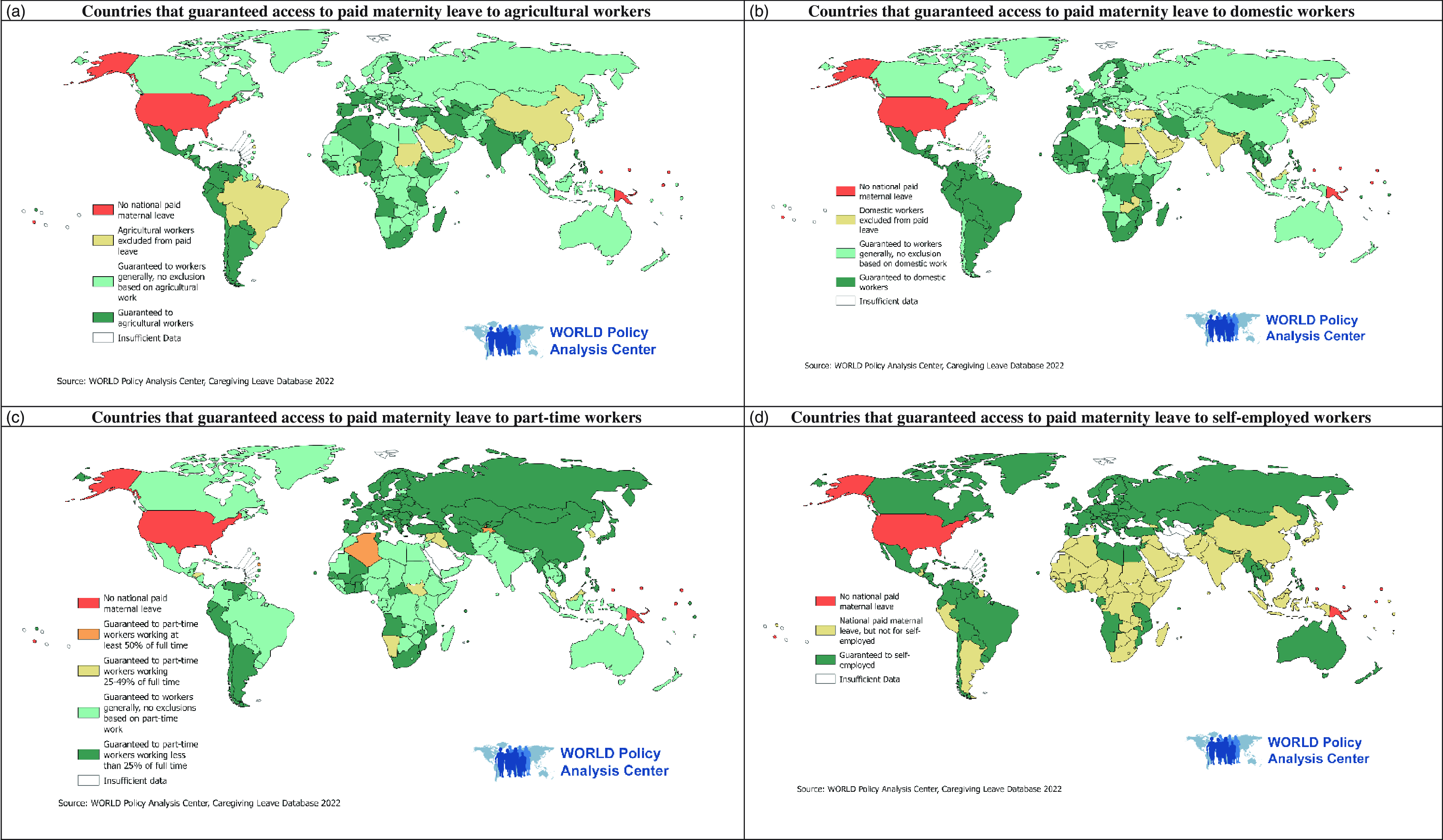

In contrast, far fewer countries take approaches to explicitly extend maternity protection to the informal economy or groups within the informal economy, the largest employer in the region. For example, only 14 countries explicitly guarantee agricultural workers maternity leave. The number of countries that explicitly guarantee this type of leave for domestic, part-time, and self-employed workers is 25, 13, and 13 respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Countries that guaranteed access to paid maternity leave to various types of informal sector workers as of January 2022.Source: https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/policies/ .

The few countries that have explicitly extended paid maternity leave to some or all women within the informal economy include Mozambique, Tanzania, and Togo. In some of these contexts, the provision of paid maternity leave stems from an enabling legislative framework that has the potential to advance maternity protection to informal economy workers more broadly. In Mozambique, for example, a universal social protection programme was established 10 years after the country’s independence through the enactment of Law 8/85 of 1985, the first law to deal systemically with social protection in the country. The Law covered themes that included health and security in the workplace, social security, female workers’ rights, unions, collective bargaining, and labour justice. In terms of labour rights relevant to maternity, the Law established that during pregnancy and after delivery, female employees should not perform tasks that are not advised in their condition; they should not work night shifts or perform extraordinary tasks and be stationed in different working sites unless expressed by the employer; they are entitled to two breaks for breastfeeding, each of half an hour without salary cuts; and should not be fired, without cause, during pregnancy and after delivery. The law also stipulates that women are entitled to 60 days of paid maternity leave, besides normal holidays, that can begin 20 days before the probable due date. To this end, this legislation coherently articulated issues of maternity protection in line with the standards set by ILO Convention 183. Subsequent laws and decrees preserved many of the principles of the former Law 8/85. These included, among others:

-

Law 5/89 on September 1989, which created the National Social Security System under which all forms of social security would be managed;

-

Decree 46/89 of December 1989, which approved the Regulatory framework to implement the social security law;

-

Decree 4/90 of April 1990, which established that workers’ contribution to social security would be 7 per cent of their monthly wage, in which the employer would be responsible for 4 per cent and the employee for 3 per cent;

-

Law 4/2007 of February 2007, which laid the foundations for the organisation of the social protection system.

All in all, the Mozambican maternity protection “legislative basket” ensures the following for workers in the country’s informal economy:

-

Maternity leave: 60 days (8.6 weeks) paid at 100 per cent wage replacement rate (WRR) through social insurance. Guaranteed to domestic workers, part-time workers (without a minimum hour requirement), and the self-employed.

-

Paternity leave: One day at 100 per cent WRR through an employer. Guaranteed to part-time workers (without a minimum hour requirement).

-

Child health leave: unspecified length of paid leave for parents to accompany children who have been hospitalised at 70 per cent WRR (paid through social insurance). Guaranteed to domestic workers on a voluntary basis, part-time workers (without a minimum hour requirement), and the self-employed.

Like Mozambique, Tanzania has enacted broad social security legislation making benefits accessible to informal sector workers. According to Lambin and Nyyssölä (Reference Lambin and Nyyssölä2022), Tanzania’s National Social Security Fund Act of 1998 represented a “pioneering” legal development in sub-Saharan Africa, in that it enabled access to formal social insurance for informal workers by allowing the enrolment of self-employed persons in the National Social Security Fund (NSSF). This was followed by the enactment of:

-

the 2008 Social Security (Regulatory Agency) Act, which urged the extension of social security to informal workers, and empowered the labour minister to introduce regulations extending social insurance access to workers operating in the informal economy.

-

the Social Security Law (Amendment) Act in 2012, which was extended to “apply to any person or employee employed in the formal or informal sector or self-employed within mainland Tanzania…”

The legal framework was further developed in 2017 when the NSSF was mandated to develop separate social insurance products for informal workers. Despite this, informal workers’ access to social insurance remains voluntary, and formal sector workers remain the primary beneficiaries of the social insurance system (Lambin and Nyyssölä Reference Lambin and Nyyssölä2022). At the same time, while the 2004 Employment and Labour Relations Act was a significant step in improving job quality and social protection for workers in Tanzania, it made no specific mention of informal workers. By the same token, the Labour Institutions Act of 2013, which regulates the payment of wages to all classes of workers, makes specific reference to agricultural workers as well as workers in the domestic and hospitality services. Taken together, this legislative framework has ensured the following for informal economy workers in Tanzania:

-

Maternity leave: 12 weeks paid at 100 per cent WRR. Two systems are available, one funded by the employer and the other funded by social insurance. Employers who are registered with the NSSF are exempted from the maternity benefit requirements under the Employment Ordinance. Guaranteed to domestic workers, agricultural workers, and self-employed.

-

Paternity leave: three days at 100 per cent WRR through the employer. Guaranteed to domestic workers, agricultural workers.

-

Leave to attend to child health: four days of paid leave for the sickness or death of the employee’s child at 100 per cent WRR, paid through the employer. Guaranteed to domestic workers, agricultural workers.

In Togo, the country’s commitment to maternity protection for vulnerable workers is explicitly addressed in Article 148 of the country’s Labor Code of 2006, which entitles women to 14 weeks (98 days) of maternity leave, including six weeks of post-natal leave. Maternity leave can be extended by an additional three weeks in the case of complications and illnesses resulting from pregnancy, childbirth, or multiple pregnancies, or for reasons related to the health of the child, duly certified by a physician. For this purpose, the period of suspension of the work contract is granted with full pay, entitling the woman to an indemnity equal to 100 per cent of the average daily wage of the insured worker during the last three months and paid up to eight weeks before and six weeks after the expected date of delivery (SSA 2019). (The benefit is paid by social security (50 per cent) and the employer (50 per cent). Other entitlements are found in Article 149 (which provides that the mother is entitled to up to one hour per workday for breastfeeding for 15 months following the birth of the child) and Article 147 (which provides that work that may harm the health of a pregnant employee or her child is prohibited).

Maternity leave was explicitly extended to the self-employed and the informal economy through a new Social Security code in 2012. In December 2021, Togo also adopted a new Labor Act (the New Code) repealing and replacing Labor Code of 2006 (the Old Code). The New Code is seen as more comprehensive than the old code in its coverage of issues (DLA Piper, 2021). In terms of social protection, the law preserved the same duration and payment structure for maternity leave and introduced the following changes:

-

Employers must provide health insurance coverage for their employees, jointly funded by employers and employees.

-

Employers have responsibility for registering workers with the social protection bodies and may face administrative and penal sanctions if they fail to comply, as stipulated by the Social Security Code.

-

All workers who have an employer have access to paid annual leave (financed by the employer).

-

Part-time workers gained eligibility for social protection, including maternity benefits.

Based on the foregoing, informal economy workers in Togo currently have access to the following:

-

Maternity leave: 14 weeks paid at 100 per cent pay (for workers with an employer)—50 per cent paid through the employer and 50 per cent through social insurance. Guaranteed to domestic workers, part-time workers (without a minimum hour requirement), self-employed workers, and informal workers.

-

Paternity leave: 2 days at 100 per cent pay through the employer, outlined in the collective agreement with broad coverage.

-

Parental leave; Child and family health leave: 10 days paid family needs leave (not specific to health needs), paid through the employer. Guaranteed to part-time workers (without a minimum hour requirement).

Examining the implementation of maternity leave for informal workers in select countries

While enacting paid leave that explicitly covers informal economy workers is a critical first step toward extending coverage, effective implementation requires that there is wide awareness of paid leave and other maternity protection benefits, that these programs are adequately funded and easy to access, and that there are avenues for recourse when employers do not meet their obligations.

To examine implementation, in the second half of this study, we undertook qualitative research focused on the three case study countries, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Togo. Data were collected from informal economy workers—including domestic, agricultural, part-time, and self-employed workers—in purposively selected urban, peri-urban, and rural localities in the three countries. Interviewees were identified with the basic inclusion criteria being that each interviewee should be a parent of young preschool-age children (0 – 5 years). This age bracket was meant to ensure that the children would have been born at a time when the relevant maternity protection legislation was in place. The interpretative phenomenological analysis approach, which aims to provide detailed examinations of personal lived experiences and how individuals make sense of those personal experiences (Smith and Osborn, Reference Smith and Osborn2015), was used to analyse the qualitative findings. Below are the brief details of the data collection processes in each country.

Mozambique

Case study data were collected in three regions: Maputo, the country’s capital and largest city; Nampula, a regional town in the north of the country; and Vanduze, a rural district of Manica located in the country’s Central Zone. Data were collected through a combination of focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with informal economy workers and employers. Key informant interviews were also conducted with government officials and representatives of agricultural unions. Of the 93 worker and employer study participants, 50 were distributed among five focus group discussions while the remaining 43 participated in in-depth interviews. Informal workers represented the following categories: agricultural, domestic, part-time workers, and self-employed street vendors.

Togo

Case study data were collected in four regions: Lomé, the capital and largest city; Plateaux, located in the southern central part of the country; Centrale, in the middle of the country; and Savanes, located in the northernmost part of the country. Data were collected through 46-key informant and in-depth interviews with informal economy workers and employers. Informal workers represented the following categories: self-employed, part-time, domestic, and agricultural workers.

Tanzania

Case study data were collected from four regions: the Kinondi district of Dar es Salaam, the country’s commercial and industrial capital; Sungwi, a rural area in the Kisarawe district; Morogoro; and Dodoma, the administrative capital city. Interviewers in Tanzania collected data through in-depth interviews of 50 workers, employers, and selected key informants. Informal workers represented the following categories: domestic, agricultural and self-employed workers. Key informants comprised government officials, representatives of civil society organisations and trade unions.

Findings: stakeholder insights on access and effectiveness

Information gaps and challenges in claiming benefits

Despite explicit legislative protections for maternity leave, informal workers across the three countries reported challenges accessing the benefits they qualified for, while many others indicated a lack of awareness that they were eligible for paid leave. Asked what maternity protection benefits she had claimed, an agricultural worker in Vanduze, Mozambique responded as follows:

“Maternity leave” in quotation marks! Why do I say in quotation marks? Because they only allowed me to continue breastfeeding for only a month after my maternity leave. However, they paid me neither during breastfeeding nor after giving birth. They said they could not pay me because they had to pay the person who would replace me when I was not able to work there. So, I spent those two to three months without pay. By then I did not know that was entitled to paid maternity leave. So I have never claimed any benefits. Maybe in the next pregnancy, I will demand them (laughs). Footnote 1

Similarly, a self-employed woman from Maputo reported that:

I did not benefit because I signed up for Social Security after I had given birth, not before. So, I still did not know of it (Social Security). Thus, I did not have the opportunity to enjoy those benefits.

Comments from a farm worker in Togo illustrated some of the information gaps about maternity protection rights, as well as their implications::

If there were laws, it would help us a lot. There are some women, for example, women in the village, when they give birth, they don’t even spend two weeks at home and they go back to the market with the baby. Often, she is not even in good shape to go back to work, but since there is no money, she has to go back to work with the child. Therefore, everyone should have the same benefits and no woman should envy the other. Currently, however, we envy working women [those in the formal economy] because they have more benefits than us (Farm worker, Togo).

According to a key informant in Togo, inadequate information on behalf of both employees and employers has limited the reach of maternity leave in the informal economy:

[The biggest challenge] is perhaps the ignorance; the ignorance of the laws by the workers and also by the employers; it is necessary that each one knows his rights; the more one knows his rights the less one makes an error, the more one knows the tests the less one creates problems.

In Dar es Salaam, one representative from the Agricultural Workers Trade Union pointed to language barriers and lack of accessible materials as one obstacle to wider awareness:

So a worker is actually entitled to be provided with these leaves [sick, maternity/paternity and accident leave]… but very sadly, the workers do not know their rights, which are actually provided for in the laws and most of our laws are in English language and most of the agricultural workers do not know the English language, even Kiswahili language itself is a problem, so also [as for those not members of workers’ organisations] they do not have a body/person to inform them [and advocate] for their rights.

Key sources of information: local governments, trade unions, and other institutions

Governments bear a key responsibility for undertaking outreach for paid leave and other benefits and social programs. Interviews made clear that all three countries had multisectoral institutional arrangements—led by government ministries or departments responsible for social protection and/or labour—to oversee the implementation of the maternity protection mechanisms as part of overall social protection provision. As the main implementing agencies of social protection laws and policies, government entities are also responsible for the monitoring and evaluation of programmes and policy implementation.

Each country’s arrangement was slightly different. In Mozambique, the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security, the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Action, the Ministry of Public Function, the National Social Security Institute, and the National Social Action Institute all play a role in implementing maternity leave and other social insurance benefits. Within the Labour Ministry, National Institute of Social Security has chief responsibility for implementing social protection, whereas the National Inspection of Labour Direction works to address violations of rights to social protection among informal workers. In Tanzania, the Social Protection Division of the Prime Minister’s Office (Ministry of Labour, Youth, Employment and Persons with Disability) has primary responsibility for implementing social protection, while the Labour Division in the same ministry is responsible for monitoring and evaluation of social protection policies. Tanzania also has a Social Protection Working Group, chaired by the Ministries of Finance and Labour, which has supported policy development and oversight of programs. In Togo, the Ministry in Charge of Financial Inclusion and Organisation of the Informal Sector, the Ministry of Civil Service, Labor, and Social Dialogue, and the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene and Universal Access to Health all bear some responsibility for the implementation of maternity protection.

In practice, interviews further revealed that in cases of disputes among entitlements, labour officers, trade unionists, and workers often resort to dialogues with employers to seek amicable resolutions. However, where an employer is defiant, these can be issued with orders and have cases instituted against them to compel them to their employees their benefits or entitlements. As a Government key informant in Tanzania explained:

If a worker is denied their benefits or entitlements, the labour officer will intervene on this matter as per Section 45 of the Labour Institutions Act, whereas the labour officer has the power to issue an implementing order to the employer to provide the worker with the rights or entitlements such as includes paid leave or any other thing a worker may be entitled to.

Alongside governments, in line with the widely documented direct link between workers’ unions and the ease of their inclusion in contributory schemes (ILO 2021), the case studies revealed the important role of informal workers’ unions and associations in increasing awareness. For example;

Labour organisations and all that … often play the role of alliances and unions. Usually, the unions are trained [and they] are good advisors who understand the laws, who explain them well. And so, the unions are there to defend the workers and their union members. So when a worker is in a difficult situation, when a worker feels wronged, they can go through a union to expose the problem and the union can accompany them in the search for a solution. … They are people who sometimes review the laws, modify them [and] distribute them. [They also] train the workers on their rights and duties and therefore in this situation, it is their duty, not only to communicate the law but also to sensitise the workers on their rights and duties and also on the procedures that they must follow to claim their rights if ever these rights happen to violated (Key informant, Togo).

It has been mainly through the monthly meetings that domestic workers are informed about their rights and benefits. These meetings are really helpful as we are able to meet up with a lot of domestic workers… at times around 200 or 300 of them would come. So, they would also get to know one another and further share information about different things amongst themselves (Representative, Domestic Workers Trade Union, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania).

It was also evident that unionised workers and those who had received some form of awareness training through labour organisations are, overall, more likely to know about their countries’ respective maternity protection laws as well as their individual entitlements. In Mozambique, for example, domestic workers affiliated with the National Domestic Trade Union demonstrated better knowledge of social security procedures and legislation due to civic campaigns organised by their union:

The paid maternity leave entitlement is important because while my employers would not pay my salary when I am on maternity leave, I will still receive my income and my monthly bills will be covered. If I fall sick and I cannot afford the treatment. I can to the National Institute of Social Security and they will pay for my treatment, provided my contribution is in order (Deputy Coordinator of Domestic Employees, Mozambique).

By the same token,

I heard about the social security benefits when I joined the domestic union. The people from the National Institute of Social Security regularly came over, or sometimes they would invite us, and we would go to them to receive information and details about how the whole social protection system works as well as what and how we can benefit (Self-employed woman, Mozambique).

The first time I heard about social security was in the union. That is when I heard about the benefits that Social Security offers to us. So, I liked it and signed up. However, before joining the union, I did not know anything (Self-employed worker, Maputo, Mozambique).

Alongside unions, schools and media emerged as notable sources of outreach and information. For example, as one domestic worker in Dar es Salaam recounted:

Some of [the laws] we have studied about in schools and others we were informed by the media channels where there have been programs discussing on the particular laws—on the employers and their employees.

Perceptions of and experiences with financing

Social security, including maternity benefits, is typically financed through social insurance where employers and employees contribute a percentage of monthly wages to a government-managed fund, from which eligible beneficiaries can apply (Pereira-Kotze et al Reference Pereira-Kotze, Malherbe, Faber, Doherty and Cooper2022).

For self-employed workers, effective coverage may require public funds to supplement the absence of an employer contribution. Key informants at all research sites in Mozambique reported that the National Institute for Social Security required a contribution rate of 7% of the employee’s salary, where 3% is directly deducted from the employee and 4% from the employer. While this rate is the same for both the formal and informal economies, employees in the latter typically pay the entire 7% rate themselves. For example:

We pay 7 per cent of the contribution for social security protection. Anyway, we are trying to look after our welfare. This is the reason why some workers are currently benefiting, from the INSS maternity leave allowance. The INSS pays for those who are making contributions … (Sub-Coordinator, domestic workers, Mozambique).

In Togo, it was not possible during the course of the case study to collect information on the cost and financing of social protection directly from the participants. However, an analysis of the legislation and existing literature revealed that employers have responsibility for paying half of maternity benefits in Togo and the other half is paid through the national social security scheme. Therefore, as much as they wish to abide by the laws, sometimes it is very expensive for employers to contribute the required proportions. This is particularly the case for the agricultural sector where the profit margin is reportedly too small for employers to afford the cost of benefits.

In Tanzania, employer contributions for all social security benefits including maternity leave range between 10% and 20% of an employee’s wages in both the public and private sector, while employees contribute up to 10% of wages. Significant reliance on employee and employer contributions may again create a particular challenge for self-employed workers who sometimes have to close their businesses when they are on maternity leave. Thus, to the extent that some businesses fail to recover after the maternity leave period, the high level of contributions is often considered an economic barrier to participating in contributory social protection schemes (ILO 2021).

Beyond leave: The importance of stronger legislative protections for all aspects of maternity protection

Key informants, particularly from civil society, recognised the critical role that an enabling legislative framework can play in ensuring that vulnerable workers are protected and their decent employment is enhanced. Some interviewees specifically noted the importance of stronger legislative provisions covering all aspects of maternity protection for informal workers, echoing prior critiques of existing legislative frameworks in the region as “underdeveloped” (Mogapaesi Reference Mogapaesi2022, 58). In essence, apart from paid maternity leave, other key elements of maternity protection (e.g. medical benefits during maternity leave, breastfeeding arrangements, and childcare support after return to work) (Richardson et al Reference Richardson, Dugarova, Higgins, Hirao, Karamperidou, Mokomane and Robila2020; Pereira-Kotze et al Reference Pereira-Kotze, Malherbe, Faber, Doherty and Cooper2022) are not explicitly guaranteed for informal economy workers. While it can be argued that these workers will be covered by the general provisions as outlined in Table 1, it is crucial to ensure that they are clearly prescribed for all categories of workers. As one key informant in Lomé, Togo stated:

… you know the world of work is a world of inequality by nature. On the one hand, there is the economically powerful employer, and on the other hand, … the worker … is in a weak position … which means that the worker is legally inferior compared to the employer who is in a superior position and therefore it is necessary to have texts that can limit the omnipotence of the employer, that’s why the labour code and all the texts that go with it, were adopted.

Similarly, holding a strong conviction that “the endorsement of these [legislative] instruments, reflects, the willingness, dedication, and commitment of the government’s agenda of improving the welfare of the workers”, a representative, of a domestic workers’ trade union in Dar es Salaam shared how they were, at the time at the time of the case studies, urging the Tanzanian government to ratify the ILO Domestic Workers Convention (No. 189 of 2011):

We are now advocating for the ratification of Convention 189 of the International Labour Organisation which we have accepted and endorsed in Geneva and which we are now supposed to ratify, and that is a Convention specifically for domestic workers. It promotes decent work for domestic workers and provides for many other things. The Convention is yet to be ratified by the government. We are now preparing a big workshop that will involve different kinds of people and stakeholders, to see why the government has not yet ratified it.

When specific aspects of maternity protection beyond maternity leave go unaddressed in legislation, workers can face further barriers to access. Indeed, insights from the case studies also illustrated how the absence of legislative provisions can lead to the provision of entitlements in an ad hoc manner and often at the convenience of the employer. For example, as a domestic worker in Morogoro, Tanzania, stated:

Because of the nature of my work, my boss did not allow me to go home to attend to my sick baby. She asked me [sarcastically] if going to the village would heal by child. She thus refused to allow me. These are some of the things that once you think of, you just accept and do nothing but wonder.

Similarly, a domestic worker in Nampula, Mozambique noted the potential consequences of taking leave without adequate and enforced protections against discriminatory dismissals:

Most of our employers … do not care about respecting the Law. However, they know about our labour rights. For instance, they know that in case of being sick or dying in our family, we have the right to get medical assistance or participate in the funeral for a few days. However, they tell us that if we go to the hospital or even if we go to the funeral, we will be replaced by another person. You see, this is because a lot of us are seeking a job.

Discussion and conclusion

With a substantial share of the world’s women working in informal employment, and with addressing caregiving fundamental to advancing gender equality in the economy more broadly, ensuring that mothers working in informal jobs have access to paid maternity leave and other aspects of maternity protection should be a high-priority issue. Alongside its implications for women’s economic outcomes, maternity protection is important to ensure that women’s and children’s health and survival are not threatened during and after pregnancy. Nowhere is action more critical than sub-Saharan Africa, which has a higher share of women in the informal economy than any other region, as well as particularly low rates of receipt of maternity benefits: just 5.9% of women who gave birth in sub-Saharan Africa received maternity cash benefits in 2023 (ILO 2024), compared to 29.6% Latin America and the Caribbean, 32.3% in South Asia and the Pacific, and a global average of 36.4%. Previous studies have attributed this poor access to maternity protection to an array of factors that include workers’ lack of or limited awareness and knowledge of maternity protection laws and/or entitlements, complicated application procedures, and other administrative hurdles. This paper both affirms these findings and expands on prior scholarship by elevating the potential roles of structural factors—specifically legislative and institutional frameworks, the role of unions and other CSOs, and the financing mechanisms for maternity protection—in expanding access for women in the informal economy.

The key finding with regard to the legislative framework is that although the vast majority of sub-Saharan African countries have not ratified ILO Convention 183, their national social protection legislations, to a large extent, have enshrined some key elements of the Convention, including 14 weeks of paid maternity leave. A major gap, however, is in relation to workers in the informal economy, the largest economy for women in sub-Saharan Africa. Only a small number of countries address paid maternity leave for informal workers, and existing laws are generally silent on other aspects of maternity protection for workers in the informal economy. By extension, this means that the largest proportion of workers in the region do not have access to requisite social protection in times of need. There is, therefore, an urgent need to recognise this important group of workers and outline laws or make explicit prescriptions in current legislation to ensure that they have access to the whole basket of maternity protection benefits as per the ILO Convention 183.

In each country, several different ministries have some responsibility for implementing maternity leave. The presence of multisectoral institutional frameworks is laudable given the potential of such a framework to harness the different partners’ strengths for more effective service provision. At the same time, while this was not a specific gap that emerged from the case studies, evidence from elsewhere (see, for example, Holmes et al Reference Holmes and Lwanga-Natale2012; Pino and Confalonieri Reference Pino and Confalonieri2014) has documented several challenges that often characterise multisectoral institutional frameworks in the area of social protection. These include inter alia weak stakeholder coordination at national and local levels; often inadequate or divergent government and partner priorities; and limited quality data for monitoring and evaluation capacity. This, suggests the need to enhance the harmonisation and alignment of stakeholders’ efforts. The latter is not only a foundation for links between partners but it can also reduce transaction costs for partners. Alignment, on the other hand, entails the building of relationships between partners to ensure that their processes and in sync (OECD-DAC, 2005). Research evidence has consistently shown how stakeholder harmonisation and alignment can enable more systematic incorporation of partner activities into decisions that can trigger systemic change; identification and addressing of capacity gaps in programming, and the capacity to address weak regulatory functions and governance mechanisms (Welle et al Reference Welle, Nicol and van Steenbergen2008).

In terms of trade union membership, it was evident that workers’ unions are effective structures in the context of the informal economy. Overall, unionised workers are more likely to know more details about maternity protection and/or entitlements. To this end, other stakeholders could also make efforts to draw good practices or lessons from unions, specifically how they teach their members about their rights, what advocacy methods they apply, and how they empower their members to ultimately position themselves to get access to the benefits. It is noteworthy, at the same time, that unions are however not a visible part of the multisectoral institutional frameworks in the countries studied. In addition, since the unions are member-based, it often becomes difficult for them to intervene when workers face challenges. Furthermore, the lack of organisation of most categories of informal economy workers makes them more marginalised, unaware of the contours of their rights, and have reduced chances of being represented in open debates (ILO 2021).

Consistent with ILO Convention 183, the three countries studied have built social insurance systems to cover maternity benefits. At the same time, financing structures that substantially rely on contributions from employees and employers may limit the affordability of leave to many informal workers in practice, particularly the self-employed, and serve as a deterrent to opting into voluntary programs. Adequate funding from general resources will be important to ensuring social insurance is affordable to more workers, taking into account both low wages in the informal economy and the potentially high-cost burden for some informal employers (Smit Reference Smit2012; Waterhouse et al Reference Waterhouse, Bennett, Guntupalli, Mokomane, Baikady, Sajid, Przeperski, Nadesan, Rezaul and Gao2022).

Finally, to the extent that social security systems are typically built sequentially, depending on countries’ national circumstances and priorities (ILO 2019), it will be worthwhile for future studies to explore the role played by countries’ political economies and histories in facilitating the provision maternity protection, and social security in general, to workers in the informal economy.

To both achieve the SDGs and meaningfully advance gender equality and decent work long term, all countries must find a way to extend basic elements of maternity protection, including paid maternity leave, to workers in informal jobs. The countries that have taken a critical first step of enshrining this commitment in legislation, including Mozambique, Tanzania, and Togo, deserve recognition for their efforts. The experiences of people within those countries can shed light on what has worked so far as well as where further work will be needed to advance implementation. As more countries follow in their footsteps, experimentation and knowledge sharing will be central to the success of collective efforts to learn and advance what works.

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of the fieldwork teams that worked in Mozambique, Tanzania, and Togo, led by Maria Judite Chipenembe, Akim Mturi, and Sethson Kassegne, respectively. We are indebted to the WORLD team members who examined in detail all laws and policies globally relevant to the informal economy, led by Amy Raub and Willetta Waisath.

Funding statement

We are grateful for the generous support of the Hewlett Foundation for this work.

Competing of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest concerning this article’s research and authorship.

Zitha Mokomane is a demographer and Head of sociology at the University of Pretoria. Her research interests are family demography, work–family interface, and social protection.

Laurel Grzesik-Mourad is a Senior Policy Analyst and Research Manager at the WORLD Policy Analysis Center with research interests that include gender inequalities and policies on discrimination in the workplace, labour, and constitutions.

Aleta Sprague is Director of Legal Analysis at the WORLD Policy Analysis Center where she examines the role of laws, policies, and constitutional rights in advancing or undermining social and economic equality across different national legal systems.

Jody Heymann is a Distinguished Professor at UCLA and Founding Director of the WORLD Policy Analysis Center (WORLD), a global initiative to improve the level and quality of comparative data on health and social policies and outcomes in all 193 United Nations countries.