Although not yet dead, those about to be deported had their bread and other items stolen from them by police officers.1 Those supervising deportations stole not only from those leaving the ghetto but also from those entering the ghetto:

The train came to a halt in an open field. The coupè doors were flung open. Tired, weary, suitcase in hand, rucksack on their backs, a bundle under their arms, more than a thousand human beings dragged themselves down the running board, stepping into deep sewage, morass, water. It was autumn, a Polish-Russian autumn. Gestapo in field-gray uniforms drove them on. “Move! Run! Run” the blond, well-nourished boys shouted. Unforgettable was the one with a reddish stubble beard and reddish eyebrows, stinging eyes, a rattling voice. He yelled at the new arrivals, “Run, you Jewish swine.”2

This was the way Oskar Rosenfeld, a Jewish author and journalist from Prague, described his arrival in the Łódź ghetto in October 1941, concluding that he and his fellow deportees were in such shock on arrival, “they even forgot that they had almost nothing to eat for a day and a night.”3 Deportations into and out of the ghettos were significant events that disrupted life in the ghetto. Deportations into the ghetto resulted in displaced people who needed to find housing, work, and food. An influx of deportees also created strains on ghetto resources, as the Germans often did not provide additional resources to meet the needs of the newcomers. Deportations might also affect food prices on the black market and disrupt family and social connections, including changing family support dynamics. The desire to avoid deportation out of the ghetto also played a role in people’s decisions about jobs, creating, in some cases, a balancing act between work that paid enough to eat and work that allowed one to avoid deportation.

Prior to 1942, deportations took place from the various ghettos to forced labor camps. The brutal conditions and poor survival rates of deportees meant that strategies to avoid deportation were developed before deportations to the death camps began.

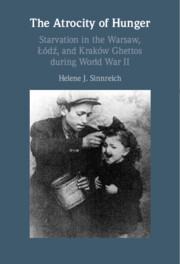

Figure 10.1 A German supervises the boarding of Jews onto trains during a deportation action in the Kraków ghetto.

During 1942, all three ghettos experienced mass deportations of nonworking individuals and individuals accused of being criminals to extermination camps. In each city, there were major deportations running from January 1942 to October 1942, which resulted in many nonworking individuals being sent to an extermination camp. In Łódź, the first wave of deportations ran from January to May, sending over 50,000 Jews or approximately one-third of the ghetto population to Chelmno extermination camp (Vernichtungslager Kulmhof ). In Kraków, the deportation in June sent one-third to one-half of the ghetto population, nearly 7,000 Jews, to Belzec extermination camp. In Warsaw, mass deportations to Treblinka began at the end of July and ended in September, resulting in the deaths of approximately 300 thousand Jews or over 75 percent of the ghetto. After this mass deportation from Warsaw, the ghetto fundamentally transformed. The remaining population of 70,000 focused on labor for the Germans, and what remained of the Judenrat was focused on supporting labor output and feeding the population. The Kraków and Łódź ghettos followed suit, with deportations that transformed them into small, labor-focused ghettos. In September 1942, a mass deportation of over 15,000 Jews, primarily children and elderly, took place from the Łódź ghetto. Known as the Szpera, the deportation left just under 90,000 people in the Łódź ghetto and significantly affected its population and character. In October 1942, approximately half of those remaining in the Kraków ghetto were transported to Belzec. Many of the Judenrat leadership were killed or deported at that time. Shortly afterward, in the final months of the ghetto’s existence, it was split into two sections, and heavy restrictions were placed not only on entering and exiting the ghetto but also on passing from one side of the ghetto to the other. In the end, people were slowly moved from the Kraków ghetto into the Płaszów concentration camp. Those not selected for Płaszów were sent to the Belzec death camp or killed. Shortly after the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto, the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto began, following a false start in January 1943 as a violent rebellion broke out, and then the Warsaw ghetto uprising of April and May. The liquidation of the Łódź ghetto came much later, in summer 1944, with deportations to Chelmno continuing until July 14 of that year, when they were halted due to the approaching Soviet Army.4 Deportations began again in August, this time to Auschwitz. Between August 15 and September 18, transports from the Łódź ghetto arrived in Auschwitz.5

Deportations into the Ghettos

Deportations of populations into the ghetto meant assimilating a large group of new people into the already crowded conditions of the ghetto and stretching food resources to feed the newcomers. Those forcibly deported from outside the city to a ghetto might face extremely difficult circumstances. New arrivals faced many hurdles when entering an established ghetto, including finding a home, a job, and a way to obtain food. Those with friends or relatives who could help them were fortunate. Those who knew no one struggled to survive and were vulnerable to being exploited. All three ghettos experienced waves of immigration, including Jews from the surrounding areas and Western Jews. New arrivals were not always able to bring with them what they wished, and a lack of valuables might leave them unable to negotiate for housing. Some became refugees in the ghettos. Warsaw ghetto survivor Edith Millman noted:

The worst off were—were the refugees from such surrounding communities because they, to start with, most of them were poor, and they could only come in with what they could carry. And they came a little bit later, so they couldn’t get rooms and apartments so shelters were established. And so people were in the shelters. And in some places, they—they couldn’t even get into a shelter. So they bedded down in basements and in attics. And these people were the first ones to really die of hunger.6

Similarly, Mary Berg commented on the stream of impoverished refugees entering the Warsaw ghetto in June 1941, noting that they “become charges of the community, which sets them up in so-called homes. There they die, sooner or later.”7

Kraków also had a population influx from outside the ghetto. Rosalie and her family were among those who, newly arrived, had to find a place to live. She described the one-room apartment they found as having “no windows and no heat. Mother, Lucy, Henry and I had one corner and eight other people divided the rest. Nobody had a job and it was too dangerous to go outside so everybody sat on the floor all day long crying from hunger.”8 Jews coming in from outside the ghetto were often in precarious situations that could lead to starvation. For example, when it came time to deport people from the ghetto to death camps, those without housing or jobs (who were disproportionately likely to be the newly arrived) were put on deportation lists.

Western Jews

Łódź, Warsaw, and Kraków all had large contingents of German-speaking Jews. Both the Łódź and Warsaw ghettos had an influx of Western Jews, including a large number of Jews from German-speaking lands. For example, in February 1941, 8,000 Viennese Jews arrived in the Warsaw ghetto.9 Kraków also had a contingent of Jews who spoke German, but these were largely Jews who had been expelled from Germany prior to the start of the war.

In Łódź, the majority of the 20,000 Western Jews came from Bohemia, Moravia, Austria, Germany, and Luxembourg and were deported into the ghetto in the fall of 1941.10 Many of the Western Jews had the advantage of coming directly from their homes, where they had not experienced the serious deprivations to which their fellow ghetto dwellers had been subjected. Despite this, they endured many difficulties in establishing themselves in the ghettos. They were in need of housing, jobs, and a means to obtain food. Although many Jews from Western Europe arrived with food and valuables, these were either taken from them or in many cases consumed quickly. For example, during April 1942, Jews from Germany who arrived in the Warsaw ghetto managed to bring only small numbers of personal items and had their gold taken from them shortly after arrival.11

The Western Jews who arrived in the fall of 1941 in the Łódź ghetto came with no more than 100 Reichsmarks, fifty kilograms of luggage, and the clothes on their back.12 Many of their valuables were confiscated. The 111 tons of food collectively brought to the ghetto by the Western Jews was confiscated for the general ghetto food warehouses. The money they brought was credited to the Jewish ghetto administration’s account for the purchase of food for the ghetto, and each Western Jew was given forty ghetto marks.13 Sometimes the items confiscated did not make their way into the ghetto administration’s coffers. In his diary entry of September 26, 1941, Szmul Rozensztajn noted that during the deportation of Western Jews into the ghetto, policemen stole bread from the newcomers’ packs.14

In Łódź, the finances for supporting the newly arrived Western Jews were maintained separately from the main ghetto population. Money for the support of the transports from Western Europe came out of workers’ salaries and money sent from abroad. Given the disproportionately advanced age of the Western Jews in the Łódź ghetto and their professional rather than blue-collar skills, they were not as widely employed as the Polish Jews in the ghetto. Furthermore, due to the bookkeeping system for collecting support funds for the Western Jews, and the debt from earlier support, most Western Jews found the majority of their salaries withheld, leaving them very little with which to support themselves.15 To avoid having to pay two-thirds of the money they received from abroad to the communal institutions that provided them with meals, many newly arrived Western Jews in the Łódź ghetto began to give false addresses for themselves, using the addresses of Jews who had been settled in the ghetto before the arrival of the transports from the West.16

Even with additional funds for purchasing food for the ghetto, new transports meant food shortages for everyone, new and old ghetto dwellers alike:

During the first five weeks following the arrival of the transports from the West, the Germans didn’t increase food allocations to the ghetto. Consequently, the same food supply was to sustain a population which had increased by 20%…. As a result, Rumkowski ordered the distribution stores to reduce the bread ration from two kilograms per six days to the same amount per week.17

The response of Western Jews to the diminished food rations was to begin to sell off their possessions in order to buy food, resulting in a radical disruption to the Łódź ghetto black market. Western Jews’ purchasing power in the Łódź ghetto drove up the price of food items beyond the purchasing power of many of the working people in the ghetto.18 The Chronicle noted that:

From the point of view of the ghetto’s previous inhabitants, this relatively large increase in private commerce has caused undesired disturbances and difficulties and, what is worse, the newcomers have, in a short span of time, caused a devaluation of the [ghetto] currency. That phenomenon is particularly painful for the mass of working people, the most important segment of ghetto society, who only possess the money they draw from the coffers of the Eldest of the Jews.19

Rosenfeld noted that in the early days of the transport, the paltry food offered in the ghetto did not yet affect the Western Jews, as many of them “still had provisions, white bread, preserves, artificial honey, canned meat, baked goods, chocolate, cakes.”20 After these provisions ran out, the German Jews began selling off their clothing items. Alfred Dube described the situation after they had consumed the food they had brought with them from Prague: “Hunger started to set in and prices of food on the black market started to climb! A single loaf of bread was selling for 10 ghetto marks.”21 Additionally, what they did bring to sell did not fetch very much in return, due to both high inflation and the desperate situation of the Western Jews. Jacob M. recalled of his arrival in the Łódź ghetto from Hamburg: “I had a new suit of clothes with me for which I had paid 350 marks in Hamburg. So you see, it was quite a piece of wealth. And I got 1 kilo of flour for it. You could purchase a pair of shoes for 100 grams of margarine and you see from these prices that objects other than food or cigarettes were worth nothing.”22

Once the possessions of the Western Jews were gone, “starvation set in.”23 Yaakov Flam, a survivor from Łódź, described the tragedy of the German Jews: “They ate what they had the moment they got it; they could not make a loaf of bread last seven days, as all the others knew how, so they ate it all on the first day, and then stayed hungry. After a short time they all died.”24 One important factor most likely affecting the very high death rate among Western European Jews, however, in addition to starvation rations and inexperience in coping with hunger, was that they were much older on average than the rest of the ghetto population. In the end, the sojourn of the Western Jews in the Łódź ghetto was rather short, as the majority were deported from the ghetto to Chelmno in May 1942, less than a year after their arrival.

The Condemned

All three ghettos had groups who were brought in during mass deportations or just before mass deportation. In Kraków, after the ghetto had been divided into A and B, there was an influx of individuals into Ghetto B, which would ultimately be liquidated. These were “Jews from the surrounding small towns” around Kraków.25 Tadeusz Pankiewicz described them as

figures in tattered garments, barefoot, hungry, infested with lice, with faces unshaven for a long time, with dazed expressions in their eyes, terrified…. The majority of them had never been anywhere outside of the villages where they were born…. They limbered like bears in a cage, continually shuffling along the barbed wire, begging for bread from passersby on side A…. The OD forbade them to leave the building. Hunger, however, proved to be stronger than any command or threat. The OD, being unable to manage them, nailed the gates and windows shut so that no one could get out into the street. Once, sometimes twice daily, they were served food like wild beasts in cages.26

Eventually these individuals were subjected to the same fate as the others in Ghetto B. Likewise, after the mass deportations from the Łódź ghetto in spring 1942, many Jews from surrounding villages were forcibly removed to the Łódź ghetto. Many would be swept up in the subsequent September 1942 deportations to Chelmno. The deportees arrived after their own ghettos had been brutally liquidated. Diarist Hersz Fogel recounted the brutal deportations from Pabianice, Brzeziny, and Zdunska Wola.27 In all three places, Jews were beaten, separated from loved ones, and subjected to long periods without food. The refugees arrived in the ghetto and soon began to suffer from hunger.

Deportations Out

In the beginning, deportations leaving the ghetto sent people to labor camps. Some volunteered for these transports for the promised food and the opportunity to support their families back in the ghetto. Often, however, these labor assignments took a deadly toll, quite literally working the person to death. Due to the brutal conditions of the forced labor assignments outside the ghettos, most ghetto inhabitants sought work in the ghetto to avoid deportation. Unfortunately, not all positions that protected against deportation also provided sufficient resources to avoid starvation; some positions were entirely unpaid, save for a bowl of soup. As a result, some people cycled between positions that paid well or provided ample food and those that gave protection from deportation.

When the deportations began to head to death camps, the lists that were drawn up tended to include those who were food insecure: people without work, people who had drawn from welfare, and people who were imprisoned for smuggling food or for selling their own food rations on the black market. Those who were food insecure were also negatively affected by the process of deportation, held in deportation sites for long periods of time as they waited for transport. In Kraków, during the June 1942 deportation actions, people were held without food and water in the square as they waited to be deported.28 Pankiewicz described how Jews being held in the Kraków ghetto awaiting deportation were denied water.29

Similarly, in Warsaw, Jews at the Umschlagplatz (deportation site) were held without food and water. Survivor Rachel Cymber recalled her brother-in-law going to get a drink of water while being held at the deportation point in the Warsaw ghetto, for which he was beaten by a German with a rifle.30 Those who tried to avoid deportation were too frightened to go into the streets even to get food, leading to days of hunger as deportations were carried out. In all three ghettos, food ration cards were regularly reissued, and those without food ration cards were also subject to deportation. In Kraków and Łódź, the Germans reissued the identification cards before and after major deportations. Some of those who hid from deportation roundups then found themselves living in the ghetto without access to rations or other licit food sources.31

The deportations had the additional danger of leaving children without parents. Warsaw ghetto survivor Anna Heilman recalled, “There were children whose parents were transported out, orphans on the streets. And you could see them from day to day sitting on the streets, getting thinner and thinner, and then suddenly getting bigger. When they were in the last stage of the hunger, they were bloated. And they used to die on the street.”32 Similarly, Kraków ghetto survivor Rosa Budick Taubman noted that after the deportations, “There were 7 year old children looking after 4 year old children, whose parents were taken away.”33 In the Łódź ghetto, Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski encouraged those in elite positions to adopt children orphaned by the deportations.

Sometimes those left behind were older children who could fend for themselves. Gusta Draenger, a resistance leader in the Kraków ghetto who broke out of jail and continued her underground activities, recorded in her diary that after one mass deportation,

Many houses in the Kraków Ghetto were missing some of their former inhabitants. Many young people found themselves alone in the world, without parents or siblings and with little property to their names. To increase their mobility, they had to convert their inheritance from deported parents into money or to liquidate it in some other way. As a result, a new fashion called “arranging a liquidation” came into vogue.34

In one such instance of “arranging a liquidation,” a group of young people met to exchange their remaining possessions with one another to meet their needs.35

The food insecure were also vulnerable to the use of food as a means to coerce people into showing up for deportation. Rosenfeld noted that people volunteered for deportation because of “insane hunger.”36 One reason for their hunger was that those who were on deportation lists had their food ration cards blocked. Later the authorities also blocked the ration cards of the families of individuals on deportation lists, so that the family did not have enough food to help the starving member until the threat of deportation had passed. Some items like ersatz coffee were available outside of rationing in the Łódź ghetto. In February 1944, Rumkowski banned the unrationed sale of ersatz coffee for thwarting deportation efforts, stating that people were subsisting on it to remain hidden.37 Food was also dangled as a lure to bring people to the deportation sites. In Warsaw, “those who reported voluntarily would receive 3 kilos of bread and 1 kilo of jam; others would be given only 1 kilo of bread and ½ kilo of jam. This enticement was clearly intended to spare the Germans some work…. The deportations began that same day, on Tisha b’Av, a fast day.”38 Warsaw ghetto survivor David Lipstadt recalled, “the hunger was unbelievable. So they offered this here bonus, three pounds of bread, for anybody who will voluntarily go to this assembly place and leave Warsaw.”39 In the Łódź ghetto, a similar tactic was used. An August 19, 1944, announcement read, “If you come voluntarily to the assembly center [for deportation], you will immediately be issued your food ration,” which was then distributed at the deportation sites.40 In the Kraków ghetto, carts of bread were baked before the deportations and wheeled into the deportation areas to be distributed to those leaving.41 In addition to feeding people at the site of deportation, the Germans tried to persuade people that they would receive work and food at their destination.42 They even received postcards to that effect from Jews who had been forced to write such lies to those still in the ghetto.

While in the barracks, all these people [who were about to be gassed to death at Chelmno Death Camp] had to write postcards to the ghetto, saying they fared well, had been given a good job, were well fed…..That’s how propaganda worked in the ghetto, and everyone wanted to leave for work, so that they would obtain good living conditions in their new place of work instead of the hunger prevailing in the ghetto. No one knew that this good job was a death sentence.43

One such postcard, received in the Łódź ghetto by a kitchen manager, said, “we laugh at your soups!”44 Kraków ghetto survivor Bernard Offen recalled:

The SS started saying that they wanted volunteers to go to another camp where there was good food and easy work. Anyone that goes is going to receive a large loaf of bread … and margarine too, and some jam. And that was such a tempting offer to people who were starving that they didn’t consider anything and went. My uncle volunteered and he was taken out of the camp.45

Jewish officials who assisted with deportations were rewarded not only with the sparing of their own lives and those of their families but also with supplemental foods. The Łódź ghetto Jewish police who engaged in deporting children and the elderly during the Szpera received one and a half kilograms of bread per day and an extra portion of sugar and sausage. Porters from Bałut Market and the Department of Food Supply volunteered for the duty for the same food ration and protection for their families.46 In the Warsaw ghetto, the police had to turn over a certain number of people to the Umschlagplatz in order to receive a receipt that they could then exchange for food.47 They could also get food and resources by accepting bribes from those trying to escape deportation. Fogel was captured in the Łódź ghetto and subjected to a medical commission to determine whether he should be deported. Writing on April 12, 1944, he noted that bread was 1,000 zloty but that one could bribe the medical commission with bread and be released from the deportation holding area.48 In the Warsaw ghetto, getting out of a street roundup cost 250 zloty, while getting out of the actual deportation site – the Umschlagplatz – ranged from 7,400 zloty plus two gold watches to 100,000 zloty.49

People sought to obtain food around the time of deportations to enable them to take food with them when they were deported.50 Cymber recalled that a man brought a giant sack of baked farfel with him to the deportation site in Warsaw.51 In the Łódź ghetto, where food was limited and smuggling difficult, this frenzy for food buying resulted in high prices for foods on the black market. Those receiving a summons sold off their belongings and poured the remainder of their ghetto currency into the purchase of food on the black market, driving up the prices.52

Prices in ghettos for food items went up with deportations not only because people wanted to buy food for their journey but also because some people decided to go into hiding and needed to stockpile food. The price of bread in the Łódź ghetto was 20–22 ghetto marks in the first half of January 1942 but rose to 30, 32, and even 35 marks in the second half of January as the deportations increased. When the deportations stopped, the price of bread fell back down to 25 marks but then rose again, back to 35 marks, on rumors of new deportations.53 Rosenfeld described the deportation from the ghetto, noting that what little household effects deportees retained were sold off to buy bread for the journey. During that time, “one kilogram of garlic was 10 ghetto marks, 1 kg potatoes 3 ½.” “A good shirt could buy 1 kg potatoes,” “bread rose to 35 marks a loaf, potatoes to 6 marks, then to 10 marks, per kg, bread rose further to 70 marks.”54 Near the central prison, where the deportees were held, the only people selling bread were the police and those who bribed them. Bread could sell for as much as 200 ghetto marks in the prison.55 On May 2, 1942, it was reported that the German police (Kripo) were taking away all possessions before deportation, resulting in wild trade in food. Food prices rose enormously. Bread went up to 700 ghetto marks, margarine to 1,000 ghetto marks, two cubes of saccharine to one mark, and three strings of chives to one mark.56 Similarly, in the Warsaw ghetto, bread prices rose tremendously around deportations out of the ghetto. Prior to the great deportation, bread was trading at around 10–21 zloty per kilogram depending on whether it was rye bread or white bread. After the great deportation began, bread prices shot up to 50–100 zloty per kilogram. By August 1942, they went up to 100–150 zloty per kilogram. By September 1942, the price of a loaf of bread had risen to 1,000 zloty.57

In order to more effectively bribe ghetto inhabitants with food to become deportee volunteers, the Germans reduced the amount of food entering the ghetto around the time of deportations. With the return of deportations at the end of February 1942, the shipments of food to the ghetto decreased. By the beginning of April, the price of bread in the Łódź ghetto had risen to 160 ghetto marks.58 This fell down to 70 ghetto marks with the announcement of an increase in food rations and the slowing of deportations, then rose back up to 110 with the announcement that the increased food allotment was meant to last through the end of May, and dropped down again to 30 ghetto marks on April 17, when potatoes were distributed. On April 18, when it was announced that nonworking individuals would be stamped, the price jumped up to 60 ghetto marks, which persisted until April 25, 1942. The price jumped back up to 160 ghetto marks with rumors of an impending deportation at the end of April.59 On May 2, 1942, however, when it was reported that the Kripo were taking away all possessions before deportation, bread went up to 700 ghetto marks.60 This initial panic subsided slightly by the next day, as Singer reported bread prices of 350 to 400 ghetto marks on May 3, 1942.61 On May 10, 1942, when the baptized Jews of the Łódź ghetto were deported, food prices on the black market increased further. Soup was 28 ghetto marks, potato peels 14 ghetto marks, potatoes 90 ghetto marks, and workshop soup 30 ghetto marks.62 In May 1942, as these prices were so wildly fluctuating, the official rations per person per day totaled approximately 1,100 calories.63 Food prices fell dramatically after the threat of deportations subsided.

Hiding from Deportation

Not everyone showed up willingly to be deported from the ghetto. In all three ghettos, individuals went into hiding to avoid deportations. While in hiding, they needed to rely on either stockpiled food or food brought to them by others. This meant that even hiding from deportation or avoiding deportation demanded food resources that were not available to many who had already expended these resources on daily survival. Those with sufficient food resources stood a better chance of remaining in hiding. In the Kraków ghetto, after the deportations to Płaszów began, groups of people went into hiding. The Germans eventually found some of these hiding spots in attics and basements: “stocked with food and water the hiders could live for months barring betrayal.”64

In the Warsaw ghetto during the great deportation, houses that had been emptied of their residents became hiding places for many avoiding deportation. One Warsaw ghetto writer recorded, “They spend their days hiding in some secret place with a secret entrance, a cubby hole or a garret and only emerge in the early morning and in the evening. They have visitors—sons, brothers, sisters—people with permission to live, who bring provisions and a few words of comfort.”65 Similarly, George Hoffman was hidden in the Kraków ghetto and relied on relatives to bring him food so he could stay in hiding.66 Additionally, individuals hiding in ghettos searched for food left behind by others. Regina Brand, for approximately the week prior to liquidation of the Kraków ghetto, went into hiding in an attic. During this time, when it was quiet at night, the men would sneak out to search for food.67

Final Liquidation of the Ghettos

In all three ghettos, sometime in 1942, the population was divided into workers and nonworkers, with the former to remain working in the ghetto, which became essentially dedicated to labor, and the latter killed or sent to extermination camps. In the end, however, all three ghettos were liquidated, with the inhabitants sent to labor camps or extermination camps. In Łódź, by the time of the final liquidation, over 90 percent of the population was engaged in work. At first, during June and July 1944, the Jews of Łódź were sent to Chelmno extermination camp. Then, after a brief lull, transports began in early August to Auschwitz, and to other labor camps in smaller numbers. The final liquidation was carried out by having whole ghetto factories deported, together with their families and equipment. This ruse, along with bribing people with food to come to the deportation site, was meant to lull the population into believing they would continue their forced labor at another location. In reality, most deportees were killed at a death camp.

In Kraków, the final liquidation involved transporting the working population to Płaszów concentration camp. This process of transferring people to Płaszów took place over time, with groups of workers being moved to the new camp. The ability to remain in the ghetto and avoid deportation was heavily tied to work permits. Eventually, a hierarchy of occupations evolved. People were divided “into three categories, marking them with signs: ‘R’: Rüstung (arms); ‘W’: Wehrmacht (army); and ‘Z’: Zivil (civilian).”68 Working for the military was perceived as providing the most protection from deportation. In October 1942, a mass deportation took much of the nonworking population to Belzec extermination camp. After that point, the ghetto was divided into Ghetto A and Ghetto B. Ghetto A inhabitants had the more secure work permits, while those in B were doomed to have their food cut off and eventually be killed. Some people in Ghetto B were able to be smuggled into A. During the final liquidation of the ghetto, those in Ghetto A were marched to Płaszów. Being in Ghetto A was not a guarantee of transfer to Płaszów, however. Many people were killed in the deportation process, en route to Płaszów, and at the camp shortly after arrival.

In Warsaw, the final liquidation of the ghetto coincided with the Warsaw ghetto uprising, which began on April 19, 1943, the first night of the Jewish holiday of Passover. The Warsaw ghetto uprising began for many Jews with a meal, the Passover seder. Many survivors reported celebrating the first Passover seder before having to find cover in a bunker. Tuvia Borzykowski recalled stumbling across a Passover seder: “The Haggadah was read by the Rabbi to the accompaniment of the incessant shooting and bursting of shells which were heard in the ghetto throughout the night.”69 Some celebrated Passover inside the bunkers.70 One survivor recalled, “Five men stand watch outside with weapons in hand. My father sits in the bunker conducting the Seder. Two candles illuminate the cups of wine. To us, it appears the cups are filled with blood. All of us who sit here are the sacrifice. When ‘pour out your wrath’ is recited we all shudder.”71

The uprising, which lasted until May 16, 1943, provided its own unique set of food acquisition challenges for fighters and those in hiding. For the fighters, the ghetto was divided into sectors run by different organizations, with uneven food availability. While some bunkers were well provisioned, most fighters had to “organize” their own food during the uprising or rotated between fighting and scouting for food. Survivor Sam Goodchild described breaking through the walls on upper floors to allow fighters passage between buildings and tearing out the staircases for the lower floors to prevent the Germans’ access.72 The fighters could then go from empty apartment to empty apartment, usually at night, to search for food left in ghetto apartments. This search for food was not without risks. Renny Kurshenbaum recalled her fear of being burned with German flamethrowers while searching for food. What they did find in ghetto apartments tended to be flour or potatoes from which they made pancakes.73 In contrast, some ghetto fighters were in bunkers that had stockpiled food.74 Marek Edelman described Mila 18 as a “luxury bunker” stockpiled with food and other necessities.75

Figure 10.2 Cooking facilities in a bunker prepared by the Jewish resistance for the Warsaw ghetto uprising.

Not everyone was a fighter during the uprising. Some people survived the uprising in hiding and had stockpiles of food, while others in hiding had limited access to food.76 Jerry Rawicki lived off rotten potatoes and apples in ghetto cellars during the uprising, which resulted in his getting sick.77 Others had to abandon food stockpiles when the building in which they were hiding was burned down. The fires consumed not only bunkers with food stockpiles but also the empty apartments with food, resulting in the displaced going for days without food. The bunkers that survived often took in more people than they had initially been prepared to support, creating food shortages even in bunkers that had been well provisioned.78 Those who were rounded up and deported during the uprising were kept under horrific conditions without food.79 Multiple survivors from that period also reported beatings, abuse, and (among the women) rapes by the guards at the Umschlangplatz.80

Conclusion

Deportations into the ghettos created food security issues for the newly arrived. Refugees in the ghetto, even those arriving with wealth, often had a difficult time finding a place with sufficient food in the ghetto. Many refugees, who arrived after having been impoverished or who experienced impoverishment and hunger in the ghetto after their arrival soon found themselves back on deportation trains, this time headed to extermination camps. A large number of refugees in all three ghettos starved to death before this transport could even happen. For those in the ghettos who were hungry, whether newly arrived or original inhabitants, food was used as a lure to bring them to the trains. Many, even some who were aware of the rumors of the trains’ destination, came to the sites of deportation so that they could eat. Others, those who felt their deportation was inevitable, spent the last of what they had to fill their stomachs before departure and to have sustenance at their unknown destination. Ultimately, those with the greatest food resources were able to put off or avoid deportation through bribery or hiding. Those who arrived in labor camps rather than death camps and who were nourished enough during the ghetto period had – assuming they were young, healthy, and childfree – a chance of surviving selections at their destination.