11.1 Introduction

In 2012, the United Nations Conference for Trade and Development (UNCTAD) proclaimed that a new generation of investment policy was emerging, one in which governments recognised the need to harness foreign investment in ways that better promoted sustainable and inclusive development. A key challenge for governments, they observed, was the need to bring international investment agreements (IIAs) into line with these objectives. As it stood, IIAs were ‘focused almost exclusively on protecting investors and [did] not do enough to promote investment for development’ (UNCTAD 2012, 7). Efforts to reform investment protection standards have grown rapidly in national and multilateral institutions since the report. These reforms range from incremental modifications to the wording and scope of key provisions to paradigm-shifting changes that aim to transform the way foreign investment is governed.Footnote 1 Investment chapters in preferential trade agreements (PTAs) have come to the forefront of reform efforts amid the declining popularity of bilateral investment treaties (BITs). What do they represent to the future of investment protection?

This chapter examines trends in the formulation of PTA investment chapters in South America, where governments were some of the first to experience the costs of BITs. Until recently, South America was the most litigated region by foreign investors under BITs, having since fallen behind Europe. As the number of BIT claims brought against South American governments grew, so too did public pressure for reform. Governments responded to these pressures differently. Ecuador, Bolivia and Venezuela took the unprecedented move of terminating BITs and/or withdrawing from enforcement mechanisms like the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Dispute (ICSID) Convention (although Ecuador since rejoined). Colombia, Chile and Peru stayed the course and expanded their investment protection commitments. Examining the political economy of international investment law reform through the formulation of South American PTAs can help us understand the role and capacity of capital-importing countries in reshaping investment protection standards in the new reform era.

This chapter makes two primary arguments. One is that domestic factors matter in shaping the articulation of investment protection commitments, even in countries that have traditionally been seen as rule-takers in trade and investment negotiations. Arguably, the legitimacy crisis now confronting international investment law has created more political space for domestic actors and institutions to shape investment lawmaking, which has contributed to experimentation with new reforms. However, the epistemic and political influence of extra-regional trade partners continues to weigh heavily on treaty-making programmes in all but Brazil, where officials are seeking to change foreign investment governance. The second argument this chapter makes is that increased variation in PTA contents may exacerbate the challenges governments face in promoting sustainable and inclusive development. On one hand, incremental reforms incorporated into investment chapters may help governments preserve greater policy space. On the other hand, increased diversity in the IIA universe can reduce the clarity of governments’ investment protection commitments and increase compliance problems. This lack of clarity may pose significant risks, especially for Peru, Chile and Colombia, which have expanded investor access to investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS).

The next part of this chapter provides contextual background by discussing the rise of PTA investment chapters amid the declining popularity of BITs. Section 11.2 focuses on the post-2012 ‘reform era’ and details the kinds of reforms reflected in South America’s PTA investment chapters. Section 11.3 discusses the drivers of these reforms, focusing on the formation of countries’ reform preferences and the role of domestic norms and actors. The final section concludes.

11.2 The Rise of Investment Chapters

In the post-war era, most South American countries fiercely opposed the standards of investment protection then championed by the United States (US) and Europe. Suspicion of foreign investors and the predominance of state-led development models favoured more protectionist management of domestic investment markets. The tide began to turn by the 1980s. Much of South America warmed to the idea that foreign investment could bring economic growth. As a result, governments looked for quick and efficient means of attracting it. Signing IIAs became the method of choice, due in part to their endorsement by influential capital-exporting countries and international organisations (Poulsen Reference Poulsen2015; Usynin and Gáspár-Szilágyi Reference Usynin, Gáspár-Szilágyi, Amtenbrink, Prévost and Wessel2018; Berge and St. John Reference Berge and St John2021). Almost 300 IIAs were concluded by South American governments in the 1990s, a leap from the handful of agreements that existed in the previous decade (UNCTAD 2005, 15). Most of these agreements took the form of BITs that were similar in nature and scope. They were short in text with broad definitions (e.g. of investors and investment) and vaguely worded standards of treatment that included most-favoured nation, national treatment, fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security. They also included compensation requirements for expropriation, all of which were backed by ISDS (Polanco Lazo Reference Polanco Lazo, Tanzi, Asteriti, Polanco Lazo and Turrini2016, 82).Footnote 2 Under ISDS, governments agreed to arbitrate investment disputes through third-party institutions, enabling investors to bring legal claims against them directly.

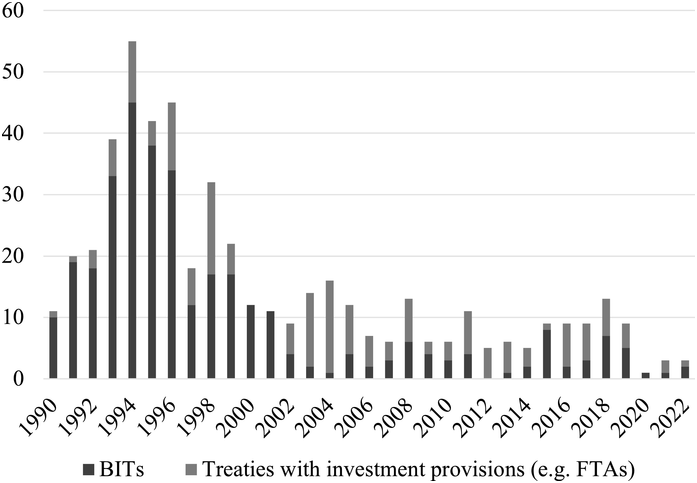

Yet, the wave of treaty signings was short-lived. Fewer than ten BITs were concluded annually after 2001, a sharp drop from the mid-1990s when forty-five agreements were signed in one year alone (see Figure 11.1). A common explanation for the declining popularity of the BIT pertains to the rise in ISDS cases. Most South American governments had experienced at least one investor claim by the early 2000s, just as treaty formulation began to slow. Scholars argue that investor claims delivered clearer and more salient information about the potential costs of BITs, leading governments to be more cautious in their treaty-making programmes (Poulsen Reference Poulsen2015), and generating demands for reform (Haftel and Thompson Reference Haftel and Thompson2018).Footnote 3 The decline in BIT signings, therefore, reflected a process of political learning whereby governments and civil society groups became more aware of the major design flaws in BITs and the potential costs they might impose.

Indeed, criticism of BITs and the ISDS system by civil society groups, academics and practitioners grew quickly in the early 2000s, leading some to proclaim a legitimacy crisis in international investment law (cf Franck Reference Franck2005; Penhardt and Wellhausen Reference Peinhardt and Wellhausen2016; Landford and Fauchauld 2018). Critics expressed concern over the ambiguity and breadth with which investment rules were written, which allowed, they argued, foreign investors to challenge a wide range of government measures as a violation of their treaty rights. This ambiguity also bestowed on international arbitrators considerable interpretative power, which some feared they would use to the benefit of investor claimants (Franck Reference Franck2005; Spears Reference Spears2010, 1040; Schill Reference Schill2017, 653). That most international arbitrators are trained in commercial law and come from a handful of prestigious (Western) institutions generated the risk that arbitrators would favour commercial interpretations of investment rules without assigning adequate significance to public interests (like human rights) and the unique challenges faced by low- and middle-income countries when interpreting the facts of a dispute (Franck Reference Franck2007; Sornarajah Reference Sornarajah, Sauvant and Chiswick-Patterson2008; Waincymer Reference Waincymer, Dupuy, Petersmann and Francioni2009; Nunnenkamp Reference Nunnenkamp2017). The practice of double hatting – when one person serves as an arbitrator in one case and corporate counsel in another – established direct incentives for international arbitrators to favour investors in their judgements (Kapeliuk Reference Kapeliuk2012, 274; Puig and Shaffer Reference Puig and Shaffer2018, 366).

Other concerns pertained to the single-liability principle and forum-shopping. The single-liability principle refers to the fact that under BITs, states assume all the obligations with very narrow grounds upon which they could hold investors liable for their own wrongdoing (Yazbek Reference Yazbek2010, 104–105; Alschner Reference Alschner2018, 240). Forum-shopping, the practice of locating operations in a country with a wide array of, or more stringent, BITs, meant that investors could exploit the patchwork of BITs to enhance their power over host-governments. Critics cautioned that these factors, combined with the exorbitant costs of ISDS proceedings would contribute to regulatory chill whereby governments fail to introduce or amend policies for fear of a costly and protracted legal battle (Spears Reference Spears2010; Tienhaara Reference Tienhaara2018; Thakur Reference Thakur2021).

Ecuador, Bolivia and Venezuela famously reacted to these concerns by terminating BITs and/or withdrawing from the ICSID Convention. Other governments continued to deepen their commitments to investment protections, albeit in a different form. Indeed, bucking the decline in BIT signings was a rise in the number of investment chapters concluded as part of broader PTAs. Between 2001 and 2011, South American governments signed thirty-four PTAs with reciprocal commitments, more than 60 per cent of which contained an investment chapter. And all but two of these chapters contained ISDS provisions. It seems somewhat contradictory that PTA investment chapters grew while BITs declined. Yet, as illustrated in Table 11.1, only a minority of countries – namely Chile, Colombia and Peru – were responsible for the growth.Footnote 4 Bolivia and Mercosur member countries continued to exclude them from their PTAs, while Ecuador and Venezuela abstained from trade agreements entirely.

2010 Bolivia-Mexico 2002 Chile-EU (1997 BIT w Austria; 1992 Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union; 1994 Croatia; 1995 Czech Republic; 1993 Denmark; 1993 Finland; 1992 France; 1991 Germany; 1996 Greece; 1997 Hungary; 1993 Italy; 1998 Netherlands; 1995 Poland; 1995 Portugal; 1995 Romania; 1991 Spain; 1993 Sweden; 1996 United Kingdom) 2003 Chile-European Free Trade Association (2003 Chile-Iceland BIT; 1993 Chile-Norway BIT; 1999 Chile-Switzerland BIT, all (i)) 2003 Chile-Korea*(i) 2003 Chile-US*(i) 2005 Chile-China (followed by 2008 supplementary agreement on investment)*(i) 2005 Chile-New Zealand, Singapore and Brunei Darussalam (1999 New Zealand BIT) 2006 Chile-Colombia*(i) 2006 Chile-Panama (1996 Chile-Panama BIT) 2006 Chile-Peru*(i) 2007 Chile-Japan*(i) 2008 Chile-Australia*(i) (1992 Chile-Malaysia BIT) | 2009 Chile-Turkey (1998 BIT signed but not in force) 2010 Chile-Malaysia 2011 Chile-Vietnam (1999 BIT signed but not in force) 2006 Colombia-US*(i) 2007 Colombia-Northern Triangle*(i) 2008 Colombia-EFTA* 2008 Colombia-Canada*(i) 2005 Mercosur-Peru 2007 Mercosur-Israel 2010 Mercosur-Egypt 2003 Peru-Thailand (1991 Peru-Thailand BIT) (i) 2006 Peru-US*(i) 2008 Peru-Canada*(i) 2008 Peru-Singapore*(i) 2009 Peru-China*(i) 2010 Peru-EFTA* 2010 Peru-Korea*(i) 2011 Peru-Costa Rica*(i) 2011 Peru-Japan (co-exists w 2008 Peru-Japan BIT) (i) 2011 Peru-Mexico*(i) 2011 Peru-Panama*(i) 2003 Uruguay-Mexico*(i) |

Note: *contains investment chapter; (i) provides for ISDS.

In some ways, PTA investment chapters signed in this period represented an early phase in the reform of international investment law. For the most part, they were written with greater detail and clarity than first-generation BITs and incorporated a limited recognition of social objectives. In some instances, investment chapters replaced BITs that were increasingly seen as outdated. Chile replaced its 1997 BIT with Korea with the 2003 Chile-Korea PTA investment chapter, which contains more precise definitions of key terms and standards. For instance, it stipulates investment characteristics and narrows the treaty’s scope and coverage.Footnote 5 The treaty also recognises environmental concerns. Article 10.18 on Environmental Measures stipulates that:

1. Nothing in this Chapter shall be construed to prevent a Party from adopting, maintaining or enforcing any measure otherwise consistent with this Chapter that it considered appropriate to ensure that an investment activity is undertaken in a manner sensitive to environmental concerns.

2. The Parties recognise that it is inappropriate to encourage investment by relaxing domestic health, safety or environmental measures.

The 1997 Chile-Korea BIT made no reference to the environment or related concerns in its vaguely worded nine-page text.

Yet, most PTA investment chapters also deepened government commitments to investment liberalisation. Investment chapters provide pre- and post-establishment rights to national treatment and most-favoured nation status, while BITs typically provide only post-establishment rights. Pre-establishment rights increase the onus placed on governments for investment liberalisation. For instance, pre-establishment rights to national treatment require that governments provide foreign investors equal access to the domestic market even before an investment is made, which affects foreign investment admissions and vetting processes. This prevents governments from imposing approval requirements or sectoral caps on the quantity of incoming foreign direct investment (FDI). Investment chapters also more often prohibit the use of performance requirements, such as those related to export volumes and technology transfer, tools that advanced economies used to promote development in the past (Chang Reference Chang2004). Therefore, while PTA investment chapters afforded governments more precision in their investment protection commitments, they also demanded greater liberalisation of domestic investment markets.

Extra-regional partners, particularly in North America, had a large impact on the contents of these chapters. For instance, the 2003 Chile-Korea PTA mentioned above shares 80 per cent of its text with an earlier PTA signed between Chile and Mexico (1998) and 75 per cent of its text with the 1996 Chile-Canada PTA. Both of these investment chapters were modelled after the 1992 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which itself heavily reflected US preferences.Footnote 6 NAFTA’s chapter 11 on investment set a new precedence in its scope and coverage, particularly in relation to investment liberalisation. It was also written with greater detail and clarity than most BITs at the time. The Chile-Korea PTA article on environmental measures is virtually identical to that of NAFTA’s chapter 11, which the US pushed for as a means to ensure that Mexico did not lower environmental standards to attract FDI. Canada, Mexico and the US used their bargaining power to push chapter 11 standards southwards through the negotiation of PTAs with South American partners. Yet, South American treaty signers were not unwilling adherents. Chile embraced the NAFTA gold-standard model, integrating into its own treaty-making programme.

The US also diffused some of the incremental reforms it adopted to its own model BIT post-NAFTA. The 2006 Peru-US PTA and the 2003 Chile-US PTA share 92 per cent of their text and carried forward NAFTA’s gold-standard, but with key changes that later appeared in the 2004 US model BIT. For instance, a key innovation of the 2004 US BIT model was the incorporation of a qualified fair and equitable treatment standard (see Schwebel Reference Schwebel and Schwebel2011).

In some countries, the decline of the BIT was met with the rise of the PTA investment chapter. The question is: why were government officials in Chile, Colombia and Peru less responsive to the emerging legitimacy crisis in international investment law than their counterparts elsewhere? And, to what extent has their stance on PTA investment chapters changed in the new reform era?

11.3 PTA Investment Chapters in the Reform Era

Since 2012, South American governments have signed twenty-one PTAs, including bilateral and mega-regional agreements. Chile and Colombia continued to lead PTA signings, followed by Peru. Mercosur countries and Ecuador signed fewer agreements while Bolivia and Venezuela abstained completely. As Table 11.2 illustrates, slightly over half (11) of the agreements contain investment chapters, down from 60 per cent in the previous decade. Of the eleven PTAs with an investment chapter, ten contain ISDS provisions. Therefore, among those countries that continue to include investment chapters in their PTAs – namely, Chile, Peru and Colombia – there continues to be a loose consensus on the merits of retaining the ISDS system. However, it should be noted that twenty-four per cent of the PTAs concluded in this period do not contain an investment chapter nor co-exist with a BIT. This is an uptick from the 15 per cent of PTAs without investment protections between treaty partners signed in the previous decade, suggesting that trade liberalisation may be becoming disentangled from the issue of investment protection.

2018 Brazil-Chile* 2012 Chile-Hong Kong (2016 Chile-Hong Kong BIT) 2013 Chile-Thailand 2016 Chile-Uruguay (2010 Chile-Uruguay BIT) 2017 Chile-Argentina*(i) 2017 Chile-Indonesia 2020 Chile-Ecuador 2021 Chile-Paraguay (1995 Chile-Paraguay BIT) 2012 Colombia-Peru-Ecuador-EU** (2009 Colombia-Belgium-Luxembourg BIT; 2014 Colombia-France BIT; 2007 Colombia-Peru BIT; 2021 Colombia-Spain BIT; 2014 Pacific Alliance Protocol; 2005 Peru-Belgium-Luxembourg BIT; 1995 Peru-Germany BIT; 1995 Peru-Finland BIT; 1994 Peru-Denmark BIT; 1994 Peru-Netherlands BIT; 1994 Peru-Spain BIT; 1994 Peru-Portugal BIT; 1994 Peru-Italy BIT; 1994 Peru-Czechia BIT; 1993 Peru-France BIT) | 2013 Colombia-Costa Rica*(i) 2013 Colombia-Israel*(i) 2013 Colombia-Korea*(i) 2013 Colombia-Panama* (i) 2017 Colombia-Mercosur 2019 Colombia-Ecuador-Peru-UK (2010 Colombia-UK BIT; 1993 Peru-UK BIT) 2018 Comprehensive and Progressive Transpacific Partnership*(i) 2018 Ecuador-European Free Trade Association 2014 Pacific Alliance*(i) 2022 Pacific Alliance-Singapore*(i) 2015 Peru-Honduras*(i) 2018 Peru-Australia*(i) |

Note: *contains an investment chapter; ** Ecuador joined in 2017; (i) provides for ISDS

The year 2012 did not mark a historic juncture in international investment law amongst treaty signers. Most treaty drafters did not depart in substantial ways from traditional investment protection standards. Rather, most PTA investment chapters continued the trend towards incremental reform. Like pre-2012 PTAs, they encompass more precise definitions of key terms than first-generation BITs, such as investment and investor, and clarify substantive protections, including those related to fair and equitable treatment and indirect expropriation. It is noteworthy however that there are strong similarities between some agreements concluded after 2012 and those concluded before it. For instance, the 2013 Colombia-Korea PTA shares 76 per cent of its content with the 2003 Chile-US PTA (Alschner et al. Reference Alschner, Elsig and Polanco2021).

More generally, though, the degree of similarity across PTA investment chapters has declined slightly over time. No PTA signed after 2012 shares more than 76 per cent of its content with another agreement, and the vast majority of agreements are closer in content to other PTAs signed after 2012. This is likely because the kinds of incremental reforms that governments are experimenting with have grown, and their usage and wording vary across agreements. For instance, Colombia’s recent PTA investment chapters with Costa Rica and Korea use an asset-based definition of investment, while the Colombia-Panama PTA investment chapter adopts a slightly more restrictive enterprise-based definition. The Colombia-Costa Rica PTA and the Colombia-Panama PTA exclude matters of taxation from the substantive scope of the treaty, but the Colombia-Korea PTA does not (although it does exclude subsidies, grants and government procurement).

It is now common for investment chapters to include procedural amendments that reduce coverage over sensitive policy areas or economic sectors and increase the transparency of arbitral proceedings. Yet, procedural reforms also vary. The Colombia-Korea PTA establishes an alternative dispute resolution mechanism alongside ISDS and disallows the submission of arbitral claims concerning disputes of a certain nature, for instance, involving measures ‘appropriate to ensure that investment activity … is undertaken in a manner sensitive to environmental concerns’ (Article 8.11). The Colombia-Costa Rica PTA does neither of these things, but it does contain stronger transparency requirements, including the public release of arbitral documents.

Another key change pertains to the incorporation of language concerning corporate social responsibility (CSR) and social objectives. Arguably, this is also where we see the greatest variation across investment chapters. The first South American PTAs to include explicit articles on CSR were the Colombia-Canada PTA and the Peru-Canada PTA, both signed in 2008. Eight of the eleven investment chapters concluded post-2012 contain such articles, suggesting South American governments have adopted them as commonplace.Footnote 7 It should also be noted, however, that CSR standards continue to depend on voluntary compliance by investors. As such, recent investment chapters do not necessarily revise the single-party liability principle. Whether they expand the grounds upon which host-states can bring successful counterclaims has yet to be seen. New provisions related to the right to regulate, environmental protection and sustainable development feature widely in post-2012 investment chapters. These provisions are meant to empower arbitral tribunals to decide case details in light of their impact on public interest matters in the hopes that governments will preserve more policy space. Yet, there is strong variation in the use of these provisions. For instance, the Colombia-Costa Rica PTA references labour standards and CSR but does not reference governments’ right to regulate beyond the treaty preamble. The Colombia-Korea PTA does not reference labour standards nor CSR but explicitly recognises the right to regulate outside of the treaty preamble.

One of the most notable changes in the post-2012 reform era is the conclusion of mega-regional PTAs with investment chapters. Investment chapters of both the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Pacific Alliance Additional Protocol share important similarities, which is perhaps unsurprising, given that the founding countries of the Pacific Alliance include two CPTPP members. They carry forward the trend towards incremental reform, but there are also some notable differences between them. For instance, the agreements differ in the restrictions placed on the use of performance requirements,Footnote 8 in their articles on expropriation,Footnote 9 and in provisions on CSR.Footnote 10 Unlike the Pacific Alliance protocol, the CPTPP investment chapter also includes an article on subrogation (Article 9.13) and explicitly provides for counterclaims in ISDS proceedings (Article 9.19.2). In broad strokes, these agreements represent the consolidation of existing investment protection standards, given they largely preserve existing norms.

Variation in the wording and scope of incremental reforms suggests that international investment law has entered a phase of experimentation as governments seek to strike the right balance between investment protection and promoting sustainable development. However, this variation may reduce the overall clarity of governments’ investment protection commitments and create new compliance problems (and greater costs). Slight changes in the wording of investment rules can generate different arbitral outcomes. For instance, Ecuador lost a US$ 75 million ISDS case to US-based Occidental after changes it made to the system of tax credits given to oil companies. It won a favourable judgement in an almost identical ISDS case brought by Canada-based EnCana. The different outcomes were due to the fact that Article XII(I) of the Canada-Ecuador BIT had more explicit language exempting matters of taxation from treaty coverage than the US-Ecuador BIT, under which Occidental brought its claim. The impact of these variations on arbitral outcomes means that governments have slightly different obligations to investors according to the IIA under which a claim is brought. In the context of limited resources, governments may struggle to monitor and enforce their compliance with their different commitments at the national level.

A second notable departure from pre-2012 trends are IIAs signed by Brazil, as in the 2017 Intra-Mercosur Investment Facilitation and Cooperation Protocol (herein referred to as ‘the Mercosur Investment Protocol’) and the 2018 Chile-Brazil PTA investment chapter. These agreements closely follow the Cooperation and Facilitation Investment Agreement (CFIA) model released by Brazil as the cornerstone of its treaty-making programme in 2015. Brazil’s CFIAs are explicitly focused on investment facilitation as opposed to investment protection and liberalisation. They exclude standard investment protections, including the highly controversial ‘fair and equitable treatment’ and ‘full protection and security’ standards, in favour of provisions aimed at encouraging cooperation between contracting parties on investment-related matters, the establishment of institutions that enhance communication between investors and host-governments (i.e. national focal points or Ombudspersons), and the implementation of dispute prevention mechanisms. CFIAs also reference CSR and forgo ISDS, providing for state-to-state dispute settlement instead.

The Mercosur Investment Protocol and the Brazil-Chile PTA investment chapter possess many of these characteristics. Article 4 of the Mercosur Investment Protocol explicitly excludes the standards of fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security and the pre-establishment phase from the agreement. The same standards are absent from the Brazil-Chile PTA. Against the rising number of PTA investment chapters with incremental reforms are, therefore, a select number of IIAs that incorporate paradigmatic change. Roberts (Reference Roberts2018) defines paradigmatic reforms as those which establish a new framework for resolving foreign investment disputes as an alternative to the ISDS system. Both treaties meet this criterion in excluding ISDS provisions, but they also surpass it in shifting the policy debate over foreign investment governance from one of investment protection to one of creating a conducive business environment through enhanced transparency and cooperation. The latter approach arguably preserves greater policy space for governments to use domestic mechanisms that aim to attract and govern foreign investment in ways that promote sustainable and inclusive development.

That Chile agreed to Brazil’s preferred investment rules as the basis for the 2018 PTA investment chapter bodes well for Brazil’s ability to scale up its CFIA model. However, Chile has pursued international rules on investment facilitation alongside its focus on investment protection and tends not to see them as competing. The Chilean government has been a keen advocate of a Multilateral Agreement on Investment Facilitation for Development inside the World Trade Organisation. Chile has also been particularly flexible towards the preferences of its treaty partners, having recently agreed with Canada to ISDS in the context of the CPTPP while also accepting the EU’s proposed multilateral investment court in the context of the EU-Chile Advanced Framework Agreement. While most of Colombia and Peru’s PTAs include investment chapters (67 per cent and 71 per cent of PTAs, respectively), 55 per cent of Chile’s PTAs do not and instead restrict investment rules to matters of trade in services and government procurement.Footnote 11 The exclusion of investment chapters in Chilean PTAs reflects the fact that investment flows between Chile and many of its post-2012 partners are covered by a co-existing BIT, some of which were concluded in the run-up to the PTA negotiations.Footnote 12 However, Chile also signed three of the five PTAs that did not include an investment chapter nor co-exist with a BIT. The only Colombian and Peruvian PTAs to exclude investment chapters are those concluded with Ecuador and Europe (i.e. the Peru-Ecuador-Colombia-EU PTA and the closely associated Peru-Ecuador-Colombia-UK PTA),Footnote 13 but Colombia and Peru already have BITs in force with the UK and major capital-exporting EU member countries.

It should be noted that South American governments also pursued systemic reforms that aimed to further institutionalise the ISDS system. South American governments announced their intention to construct an alternative ISDS system under the banner of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) in 2010 that would rival ICSID. Their proposal included a new centre for investor–state arbitration, a code of conduct for arbitrators and mediators and a counselling centre for investment disputes. The arbitration centre was to include an appellate tribunal through which member states could submit arbitral judgements to review in the hopes that it would add greater consistency and predictability to the application of investment rules (Fiezzoni Reference Fiezzoni2011). UNASUR representatives met to finalise the agreements in January 2016; however, momentum behind the initiative faded as political support for UNASUR waned amongst key member states. The initiative has since been shelved entirely, suggesting that governments have moved away from the idea of finding a regional answer to the reform question.

Post-2012, the IIA network in Latin America, looks increasingly diverse. First-generation BITs have been layered and sometimes replaced with second- and third-generation PTA investment chapters that encompass a wide range of reforms. Most IIAs now reflect a dominant preference for incremental reform, but paradigmatic reforms are appearing at the margins. Reforms of any degree may help governments better preserve public interests with promising results for sustainable and inclusive development given the significant limitations of first-generation BITs. However, they also threaten to further fragment an already complex area of international law. The danger then is that reform efforts are exacerbating – not alleviating – the very challenges that may hamper governments’ abilities to meet development goals. What is driving these trends is the subject of the next section.

11.4 The Drivers of Reform

In accounting for PTA trends, we can differentiate between what governments want (their preferences) and what they agree to (treaty outcomes). Trade preferences are the set of rules that governments believe will generate the greatest economic and political benefits. They are informed by interest groups, political leadership (e.g. ideology and societal linkages), and beliefs about trade and investment liberalisation. Treaty outcomes are often an amalgam of country trade preferences, inter-state power politics and efficiency-seeking behaviour. All governments tend to sacrifice some of what they want to secure higher-order preferences. How much a government sacrifices is the result of uneven bargaining power (Putnam Reference Putnam1988). At the same time, the complexity of trade and investment rules and scarce government resources creates incentives for governments to rely on ‘boilerplate’ provisions found in their own IIAs or in those of treaty partners (Peacock et al. Reference Peacock, Milewicz and Snidal2019).

The similarities across many post-2012 PTA investment chapters suggest that governments continue to rely on standardised language in their treaty drafting, even as these standards slightly change. Peacock et al. (Reference Peacock, Milewicz and Snidal2019) argue that this kind of behaviour stems from efficiency-seeking behaviour as governments seek to lower negotiating and drafting costs, and incorporate accumulated knowledge into an increasingly complex and nuanced set of agreements. Bargaining power dynamics also continued to shape the content of most South American PTAs, with the exception of those signed by Brazil. Post-2012 saw several instances in which these governments negotiated PTA investment chapters in a position of weaker bargaining power. In the TPP negotiations, Chile and Peru were disadvantaged relative to wealthier trade partners like the US, Australia, Canada, Japan and New Zealand.Footnote 14 The US, in particular, had a strong influence over that agreement, having used its bargaining power to shape the investment chapter after its own model BIT.Footnote 15 After the US withdrew in 2017, the CPTPP investment chapter went relatively unchanged. Exceptions include slight modifications to the definition of covered investment and a narrower scope to ISDS coverage.Footnote 16 Colombia was also arguably at a disadvantage when it signed agreements with Israel and Korea in 2013, which favoured incremental reform and preserved ISDS.

Yet, Chile, Colombia and Peru were not pulled towards more stringent investment protection standards that they otherwise did not support. That Chile, Peru and Colombia themselves supported these standards (albeit in a modified form) is evidenced by South-South PTAs and BITs signed in this period. Stark differences in development status and market size did not characterise other PTA negotiations where incremental reforms were included. They were also included in investment chapters where South American governments arguably had the advantage, as in the case of the Peru-Honduras PTA and the Colombia-Costa Rica PTA. Chile may have had an advantage in PTA negotiations with Uruguay and Paraguay, but the parties addressed investment protection in stand-alone BITs with incremental reforms. That all three countries negotiated a stringent investment chapter with incremental reforms as the basis of the Pacific Alliance agreement further illustrates this point. Bargaining power and efficiency seeking therefore helped shape the content of many South American PTAs in the reform period, but they do not explain why governments were willing to negotiate these agreements in the first place nor their continued support for standard investment protections. Here, it is necessary to consider other factors.

Another explanation for incremental reform preferences in these countries pertains to their experience in ISDS. As illustrated in Table 11.3, the countries vary in the timing and frequency of investor claims. Peru faced its first ISDS case in 1998, and it has been sued relatively frequently. As of January 2023, at least thirty-one ISDS cases have been brought against the country under IIAs. Chile faced its first claim in 1998, but it has faced fewer total claims overall (seven). Colombia experienced its first ISDS case in 2016, but claims against the country grew quickly, reaching twenty ISDS cases by 2023. All three governments have won more cases than they lost, and the awards rendered against them have been relatively small.Footnote 17 Peru has won six cases (with costs) and lost two, settling or having discontinued four additional cases. Chile lost its first case, but the US$ 10 million paled in comparison to the US$ 515 million sought by the investor in that dispute. In total, Chile has won three cases and lost two, with two more cases pending. Colombia has won five of the cases, lost one and the others are pending.

| Country* | Cases as respondent | Cases as home-state | Year of first claim against (outcome) | Wins | Losses | Settled or discontinued | Pending |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 62 | 5 | 1997 (investor win) | 6** | 19 | 28 | 9 |

| Bolivia | 17 | 1 | 2002 (settled) | 0 | 3 | 10 | 4 |

| Chile | 7 | 9 | 1998 (investor win) | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Colombia | 20 | 4 | 2016 (investor win) | 5 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| Ecuador | 24 | 0 | 2002 (settled) | 6 | 8 | 4 | 7 |

| Paraguay | 3 | 0 | 1998 (State win) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Peru | 31 | 3 | 1998 (settled) | 6 | 2 | 4 | 19 |

| Uruguay | 5 | 1 | 1998 (State win) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Venezuela | 53 | 1 | 1996 (investor win) | 12 | 17 | 10 | 14 |

The incremental reforms adopted by governments suggest a degree of policy learning about the dangers of overly broad and ambiguous treaty provisions (Haftel and Thompson Reference Haftel and Thompson2018). According to Rivas (Reference Rivas and Brown2013, 195), who headed Colombia’s treaty model drafting and Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiations in the Ministry of Trade, updates to Colombia’s 2017 model BIT were in part a result of the wave of treaty claims brought against it. A positive track record in ISDS proceedings may confirm for officials the overall benefits of their investment protection commitments and the impartiality of ISDS, in turn generating preferences for incremental reforms that retain the perceived benefits of the existing system. Countries that have terminated BITs (as in Ecuador) or withdrawn from ICSID have poor track records in ISDS proceedings.

Yet, investor claims do not alone explain the extent or timing of government reform preferences. It does not explain why Colombia updated its BIT model in 2006, 2008 and 2011, well before its first ISDS case. Outside of Peru, Chile and Colombia, governments that have not lost an ISDS case prefer systemic or paradigmatic reform. For instance, Indonesia refused to renew BITs with a host of partners despite having never lost an ISDS case.Footnote 18 Australia announced a ban on ISDS provisions under its Labour government in 2015, having only faced one claim, which it won (Calvert and Tienhaara Reference Calvert and Tienhaara2022). Other governments like Argentina, which lost several costly ISDS cases, did not pursue paradigmatic reforms. Reform preferences, therefore, do not map neatly onto countries’ arbitral records.

Another explanation for reform preferences pertains to countries’ domestic landscapes and pressures. That government officials in Peru, Colombia and Chile held similar reform preferences after investor claims suggests that they may have been responding to similar domestic factors. One of these factors pertains to the normative beliefs held by the policymakers themselves.

Normative ideas – for instance, about the merits of economic liberalism and the appropriateness of IIAs in attracting FDI – serve as the filter through which individuals determine what they want to see in the information that confronts them. As such, they are key drivers of confirmation bias. In theories of bounded rationality, the habit of individuals to assign greater significance to information they ‘want’ to believe is referred to as confirmation bias or motivated reasoning (Poulsen Reference Poulsen2015, 26). The key here is that different normative priors can orient confirmation bias in different ways, leading to competing interpretations of the same information (Calvert Reference Calvert2022). This is why two countries that win in ISDS proceedings may view their investment protection commitments in a different light. That Chile, Colombia and Peru continued to expand their investment treaty commitments while other countries with positive track records in ISDS proceedings did not reflects the potential influence of different normative belief systems.

That government officials across all three countries shared a normative commitment to investment protections, and international arbitration, is evident in the statements made by officials in relation to ISDS cases. Here, state discourse across the countries bears striking similarities. Namely, state officials tended to affirm the state’s commitment to extant international legal obligations and praised the authority of arbitral tribunals while highlighting the countries’ positive track records in ISDS proceedings. For example, in response to Colombia’s loss in an ISDS case brought by mining giant Glencore, officials from the National Agency for the State’s Legal Defense, which manages the state’s response to investor claims, stated that the Agency ‘respects and recognises the powers of international institutions and is convinced of the use of [these] dispute resolution mechanisms that resolve cases more promptly’ (El Tiempo Reference Tiempo2020). The statement was made even while the Agency sought annulment of the award.

When Chile was presented with a new ISDS claim in 2021, government officials emphasised Chile’s ‘undisputed track record as a country that offers its investors a treatment consistent with its international obligations’, a claim that was ‘supported by the fact that [Chile] has faced a very low number of investment arbitrations as defendants and has been victorious in all but one of the cases’ (Peña Reference Peña2021). In response to Peru’s loss in an ISDS case brought by Canadian mining company Bear Creek, former Minister of Economy and Finance Alonso Segura dismissed criticism of the award, arguing that: ‘In reality, [the losses] are healthy because it is part of the rules of the game of being a country with strong investment. These cases in which we have effectively lost were those where there were arguments to lose, but we won the majority. That’s the way it works’ (Lozano Reference Lozano2019).

These statements can be interpreted as an effort by government officials to reduce the reputational fallout resulting from ISDS cases. However, the fact that officials felt beholden to these pressures suggests they continued to see value in foreign investment attraction and believed that the current system of investment protection was the most appropriate means of attracting it. While they are sensitive to criticism of IIAs and the ISDS system, their belief overall in the merits of investment protections as enshrined in international law means that they are more likely to view the problem as a need to ‘fine-tune’ the existing system. In other countries, like Ecuador, government officials emphasised the sovereignty costs associated with IIA commitments in their calls for systemic and paradigmatic reforms (cf Calvert Reference Calvert2022).

This is not to say that normative beliefs are a causal driver of treaty outcomes, rather that they play a role in determining policymakers’ first-order preferences and, in doing so, make them more or less susceptible to supporting incremental reforms in the context of PTA investment chapters. However, for particular beliefs to acquire significance in policymaking processes, they require favourable actors and institutions (Béland Reference Béland2009). The political economy of trade and investment policy in Peru, Colombia and Chile differs in important ways, but each country provides (at least until recently) a conducive environment for the dominance of pro-market belief systems.

In Chile, there has historically been a broadly held consensus between mainstream political parties on the merits of IIAs and the ISDS system. This consensus formed in the 1990s in the wake of the dictatorial and right-wing government of Augusto Pinochet. Pinochet initiated a process of rapid economic liberalisation, restructuring economic sectors and state institutions to facilitate market-led development. Following Pinochet’s defeat in a 1988 plebiscite, left- and right-leaning political parties converged on a set of norms that would guide democratic renewal. The ‘Chilean consensus’ was formed around a belief in the sanctity of the rule of (international) law and the idea that electoral democracy was best complemented by free-market economics (Fermandois Reference Fermandois, Gardini and Lambert2011, 37). Pose (Reference Pose2019) attributes the consensus to the initial success of structural adjustment under Pinochet and to pro-market technocrats, who helped embed support for free-market economics in key bureaucratic institutions. Business associations were initially lukewarm towards government plans to negotiate PTAs, but over time those who won out from trade liberalisation became fervent supporters of the integrationist agenda, leaving the consensus unchallenged.

Support for trade and investment liberalisation remained strong within the political class over time. Two decades of centre-left leadership under the Concertación failed to generate substantive departures in foreign economic policy despite its strong ties to labour and other left-leaning groups who were critical of PTAs. Heading into the reform period, Chile was led by the centre-right coalition of Sebastián Piñera (2010–2014, 2018–2022), a keen advocate of economic liberalisation. Piñera was replaced by the centre-left government of Michelle Bachelet (2006–2010, 2014–2018), which continued the pro-trade agenda even while moderating neoliberal measures in areas of social policy.

Recently, it appeared that Chile would fail to ratify the CPTPP agreement and complete negotiations with the EU on a modernised trade agreement due to opposition from civil society and smaller left-leaning political parties who opposed ISDS. Critics feared the agreements would empower multinational corporations while disadvantaging indigenous groups and workers. Gabriel Boric, who firmly opposed the CPTPP as a member of the Chamber of Deputies, promised to veto the agreement if elected president. Once Boric came to power in 2022, he retracted his promise out of respect for the democratic process, which saw the CPTPP agreement pass through two legislative bodies.Footnote 19 Boric’s decision to ratify the agreement confirms the normative link between electoral democracy and free-market economics that has been embedded in Chilean political institutions. As first observed by Polanco Lazo (Reference Polanco Lazo, Tanzi, Asteriti, Polanco Lazo and Turrini2016, 133), the Chilean legislature has continued to ratify all PTAs with support across mainstream political parties.

In Peru, economic elites and technocrats have a stronger hold over the reform debate than elected politicians. Politicians in Peru tend to be more inexperienced than their counterparts in Chile and Colombia and they often lack the backing of an institutionalised political party. The dominance of foreign economic policy by technocrats and economic elites in Peru reflects the historic influence of the Fujimori model of market-led development. In the 1990s, the semi-autocratic government of Albert Fujimori adopted a sweeping and rapid programme of economic reform in what became known as the ‘Fujishock’. Fujimori reformed state institutions to ease his agenda, appointing outward-looking elites trained in prominent Western institutions and previously employed in international financial institutions to key bureaucratic and political posts. Technocratic elites and economic advisors defended the model over changes in government while entrenching economic integration as a cornerstone of Peruvian foreign policy. Technocrats had strong ties to Peru’s business community, in particular the domestic representatives of foreign-owned companies, who influenced trade and investment policy through corporatist and personalist linkages.

As a result, Peru’s support for traditional investment protection standards remained stable despite the election of political leaders who were themselves critical of trade and investment liberalisation. Ollanta Humala (2011–2016), a left-leaning candidate of indigenous descent, denounced the TPP negotiations in his presidential campaign. Over time, the Humala government embraced the TPP negotiations and signed onto the Pacific Alliance agreement. Centre-right presidents deeply committed to trade and investment liberalisation were also elected, rotating power with left-leaning figures. Notable was Alan García (2006–2011), who was backed by the American Popular Revolution Party (APRA), Peru’s oldest and most institutionalised political party. The point, however, is that Peru demonstrated remarkable consistency in its reform preferences across changes in the executive branch due largely to the influence of bureaucratic and economic elites and weakness in the political party system, which meant opposition parties did not form an effective veto point in legislative debates on investment policy (see Calvert Reference Calvert2022).

A slightly different constellation of actors and institutions dominates reform debates in Colombia. Colombia too embarked on a period of economic and bureaucratic reform, which escalated in the 1990s according to neoliberal dictates. As in Peru and Chile, bureaucratic modernisation empowered pro-market technocrats in foreign economic policy circles who promoted economic integration (Villaveces-Niño and Caballero-Argáez Reference Villaveces-Niño, Caballero-Argáez, Sanabria-Pulido and Rubaii2020). For the most part, technocrats saw willing proponents of trade and investment liberalisation in the executive branch. Post-2000, Colombian elections saw to power right-leaning governments whose foreign policy was closely aligned with that of the US (although to varying degrees).Footnote 20 That government officials took inspiration from US trade agreements in their redesign of Colombia’s model IIA reflects a broader and more historic deference to US foreign policy. Rivas (Reference Rivas and Brown2013, 195) notes that trade negotiators learnt the importance of more detailed provisions during the Colombia-US FTA negotiations, which inspired changes in Colombia’s 2006 model BIT. However, Colombian officials did not blindly follow the US. The impetus for BIT model updating also came from a bureaucratic impulse to keep up with international trends in PTA investment chapters. Model drafters also reviewed ICSID awards and decisions and consulted closely with UNCTAD officials concerning the incremental reforms made by other governments. More recently, the Constitutional Court has also weighed into the reform debate in demanding the issuance of interpretative statements to enhance the compatibility of certain substantive investment protections with the Colombian constitution (see Suárez Ricuarte Reference Suárez Ricuarte2019).

Interest groups have influenced the country’s trade agenda and its IIA programme, but they have sometimes served as roadblocks. For instance, opposition from influential interest groups to a proposed PTA with China in 2012 led to the demise of that agreement. As a substitute, the executive branch focused its efforts on pushing forward the ratification of the Colombia-China BIT, which had been left outstanding since 2008 (Long et al. Reference Long, Bitar and Jiménez-Peña2019). Generally, investment liberalisation is less contested by interest groups, which may have reinforced support for BITs. The executive branch is, therefore, not isolated from interest group pressure, but political leaders exert more independent influence over the reform debate than in Peru insofar as it is their preferences that matter. This was most recently illustrated by changes to Colombia’s IIA programme after the 2022 election of Gustavo Petro. Petro, a left-leaning economist and former guerrilla fighter, has called for the renegotiation of Colombia’s PTAs with a focus on rewriting investment protection clauses that threaten the environment.

In 2023, the Petro government signed a BIT with Venezuela despite international condemnation of the Maduro regime. It is likely that that agreement was the result of political strategising by Petro, given the need for Venezuelan cooperation in Colombia’s ongoing peace talks with the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN, National Liberation Army). Most importantly, the BIT provides for ISDS despite the previous rejection of that system by the Maduro government. However, the treaty substantially modifies key protections by emphasising the limits of those protections and the parties’ regulatory powers. It also excludes several traditional substantive protections, that critics identify as the most problematic, such as fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security and most-favoured nation treatment. Who dominates reform processes therefore varies in important ways across Peru, Colombia and Chile. However, the common factor is that all of these actors had subscribed, until recently, to the merits of strong investment protections.

The impact of domestic beliefs on IIA reform is also evidenced by the case of Brazil. Brazil is one of the few countries that has never ratified a traditional IIA. Although it signed a swath of BITs in the 1990s, legislators voted against the agreements for fear that they would constrain national policy space and favour foreign investors over their domestic counterparts. Concern for the equal treatment of national and foreign investors is an enduring legacy of the Calvo Doctrine, a nineteenth-century doctrine which held that foreign nationals should not be given privileged access to supra-national institutions through which to resolve legal disputes with their hosts since domestic investors had been given no such privilege. Brazilian officials have long rejected ISDS on this basis. The national treatment norm largely persisted in the political class. One explanation for its endurance pertains to FDI attraction. FDI inflows to Brazil accelerated over time despite the country’s failure to ratify BITs. According to Vidigal and Stevens (Reference Vidigal and Stevens2018, 486–487), success in attracting FDI likely confirmed for political elites the BITs were not necessary to secure an economic advantage.

Brazil launched a new treaty-making programme in 2015 under the leadership of Dilma Rousseff (2011–2016) based around the CFIA. The launch of Brazil’s CFIA model appears to have been driven by interest group pressure and a growing preference for regional and global integration. Brazil’s business community expanded rapidly over the past two decades, particularly in the areas of agriculture and natural resources. As a result, Brazil became a significant exporter of FDI, particularly to other global South economies. By the 2010s, Brazilian investors had begun pushing the government for rules that would ease their outward investment. Domestic norms continued to have a strong impact. Namely, the CFIA model avoids infringing on the national treatment norm by focusing squarely on the issue of investment facilitation and forgoing investment protection and ISDS entirely. According to Moraes and Cavalcante (Reference Moraes and Cavalcante2021), much of the business community accepted the principle of equal treatment and did not press for BIT-like investment protections. They instead sought frameworks that would encourage governments to strengthen their business environment for investment and reduce the transaction costs associated with navigating bureaucracies and opaque regulation.

Arguably, the legitimacy crisis in international investment law has created more space for policy experimentation in South America as governments face less pressure to adhere to a one-size-fits-all set of investment protections. The bargaining power of extra-regional players and their epistemic influence in leading incremental reform continues to weigh heavily in treaty-signing countries. However, the domestic politics of investment policy continues to change, and it will have important ramifications for the future of international investment law.

11.5 Conclusion

Momentum towards the reform of international investment law has grown since 2012. Governments are seeking ways to better protect their policy space and prevent frivolous investor claims. Yet there appears to be little consensus on the extent of reforms required. In Colombia, Peru and Chile, governments tend to view IIAs as consistent with their development goals, at least until recently. As such, they have favoured incremental reforms and advanced them in a new generation of PTAs. But they have also been responsive to the demands and institutional realities of regional and extra-regional partners. As a result, PTA investment chapters vary in their contents (although, in most instances, to slight but significant degrees), and a growing number of PTAs exclude them entirely. Outside of these countries, reform preferences range from systemic to paradigmatic. Brazil’s CFIA model poses the most successful example of paradigmatic reform in the region. To date, it is the only alternative IIA model to inform a PTA investment chapter, but it appears to be overlapping with – not displacing – traditional investment protection standards.

The spaghetti bowl of IIAs looks more complicated and incomplete now than ever before. And recent developments in Chile and Colombia suggest that reform preferences may be subject to change in the short term. Moreover, the impacts of incremental reform on government regulation and, in particular, their ability to promote sustainable and inclusive development has yet to be understood. It is likely that they will not be known until further ISDS judgements are rendered. Governments continue to operate in an arena of high uncertainty, given that a significant degree of interpretative power remains in the hands of arbitrators in a system that continues to be decentralised and ad hoc and where governments lack powers of review. In this circumstance, ISDS cases will continue to deliver important information. However, the lessons governments draw from these opportunities will depend on who dominates reform debates and the beliefs they hold about the relationship between investment protection and sustainable development.

For now, PTA investment chapters present both challenges and opportunities for current reform efforts. On the one hand, PTA investment chapters have provided governments with the opportunity to update investment protection standards and procedures for resolving investment disputes. For weary governments favouring reform, replacing an existing BIT with a PTA investment chapter poses fewer reputational risks than terminating or renegotiating a standing treaty. On the other, investment chapters appear to be contributing to fragmentation in international investment law, which will increase the hurdles for governments in seeking to comply with their investment protection commitments. PTAs may also slow the pace of future reform since they are more difficult and cumbersome to renegotiate than BITs (or CFIAs) once they are put in place. PTA investment chapters, therefore, may generate new challenges for governments seeking to reform their investment protection commitments in the future.