Introduction

The Republic of Serbia is a continental country located in Central and Southeastern Europe. Serbia belonged to Yugoslavia (which was made up of countries), which began to disintegrate in 1999 when the assemblies of Slovenia and Croatia declared independence. The joint state of Serbia and Montenegro was formed in 1992 and dissolved in 2006 (Todorović Reference Todorović2021). In 2008, the newly formed Serbian government emphasized European integration as a key national objective. Guided by this ideology, the government intensified legislative activity in 2009, aiming to align national laws with EU standards and meet the goal of EU accession. Serbia formally applied for WTO membership in 2005 and for EU membership in 2009. As part of the integration process, it committed to harmonizing over 22,000 EU laws and regulations, including those related to quality infrastructure.

Based on principles from the WTO and the EU, state institutions establish requirements that products must meet before entering the market, reflecting consumer expectations. An established quality infrastructure (QI) is essential for every country to achieve its social goals, influence global trade, reduce technical barriers and facilitate market access (Katsieris Reference Katsieris2024). The International Network of Quality Infrastructure has recently redefined quality infrastructure as a system comprising organizations, policies, legal frameworks, and practices necessary to ensure the quality, safety, and environmental soundness of goods, services, and processes (INetQI 2022). According to EU rules (new good package), quality infrastructure laws in Serbia represent the legal basis for the adoption and application of technical legislation consisting of (a) the Accreditation Law, (b) the Standardization Law, (c) the Metrology Law, and (d) the Law on Technical Requirements for Products and Conformity Assessment.

Based on the comparative analysis done in Ruso and Filipović (Reference Ruso and Filipovic2020), it can be concluded that Serbia, as a pre-accession country, lags behind EU states such as Slovenia and Croatia. They have established National Quality Infrastructures (NQIs), both in the institutional sense and in terms of compliance with European standards (Lovrenčić Mikelić Reference Lovrenčić Mikelić2020). Slovenia and Croatia have more stable accreditation, metrology and standardization systems, with greater integration into European and international networks (e.g. membership of EA, ILAC, IAF, etc.). On the other hand, Serbia is making progress but still has limitations in institutional capacity and the perception of the importance of NQI among policymakers. Compared with Montenegro and North Macedonia (non-EU countries), Serbia has a slightly more developed infrastructure, but the challenges are similar, especially regarding policy implementation and limited resources.

Although the common problems of the transposition of EU legislation in Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs) are widely studied, our knowledge about how public policymakers perceived quality infrastructure issues in Serbia during the EU pre-accession process is still limited. Therefore, the article is based on the research question of what MPs’ parliamentary discourse of NQI laws reveals about their understanding, priorities, and value orientations concerning standardization, accreditation, conformity assessment, and metrology. The methodological framework of the article is based on a qualitative analysis of the content of shorthand notes from the sessions of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia, which refer to the consideration and adoption of laws in the field of NQI. This analysis aims to identify the dominant narratives, attitudes and arguments that MPs put forward during discussions on laws that regulate the areas of standardization, accreditation, conformity assessment and metrology. Concrete legislative proposals in the period from 2009 were analysed, and special emphasis was placed on the frequency of appearance of the term and the type of discourse. Results show that the laws concerning quality infrastructure were adopted without engaging the public in open debate and were primarily seen as formal obligations imposed by the European Union. This perception overshadowed their potential role as strategically important reforms tailored to strengthen Serbia’s institutional framework, enhance competitiveness, and support long-term socio-economic development.

Literature Review

After the collapse of the Soviet bloc, EU accession became a key goal for CEECs. The process of aligning with EU laws (Acquis Communautaire) accompanied their transition, though differences among countries sometimes caused distortions and unfavorable outcomes (Jiroudková et al. Reference Jiroudková, Anna, Strielkowski and Slosarcík2015). The EU accession process is widely perceived as one of the most powerful tools at the disposal of the European Union for the international promotion of democracy and the rule of law (Bazerkoska Reference Bazerkoska2023). European states aiming to join the EU must undergo ‘Europeanization’, involving structural reforms, strengthening administrative capacity, aligning laws and regulations, and adopting necessary standards and policies to meet accession conditions (Balan Reference Balan2022). Nevertheless, in this process of EU accession, a substantial body of literature highlights common challenges such as ‘shallow Europeanization, Potemkin harmonization, the “rubber stamp” effect, empty shells, and the world of dead letter’ (Ruso and Filipović Reference Ruso and Filipovic2020: 277). The problem lies in the normative acceptance of EU standards, which is not followed by their actual implementation. Despite formal harmonization, national legal systems remain tied to previous value frameworks rooted in the ideologies of dominant social groups, who are often reluctant to abandon them (Nadazdin-Defterdarevic Reference Nadazdin-Defterdarevic2015).

Therefore, for instance, during the adaptation of legislation to European standardization and certification in Ukraine, policymakers’ efforts to adopt legislation in the relevant area have not yet been crystallized in the expected results at the macroeconomic and sectoral levels (Derevyanko et al. Reference Derevyanko, Neal, Lazarenko, Bolotina and Zelensky2021). Other issues are related to capacities, resources, and qualified people. In the same train of thought, Xhuvani and Mecalla (Reference Xhuvani and Mecalla2023) concluded that in Albania, better functioning of structural and administrative capacities is needed, requiring a dedicated additional budget and trained staff. Although many authors point to enormous economic, political and administrative challenges among CEECs (Ruso and Filipović Reference Ruso and Filipovic2020; Butković and Samardžija Reference Butković and Samardžija2014; VanDeveer and Carmin, Reference VanDeveer and Carmin2012), EU enlargement benefits are still reflected in financial assistance, increased competition, increased economic certainty, reduction of corruption, etc., coupled with a negative effect from harmonisation costs (Kolesnichenko Reference Kolesnichenko2009). In order to provide a benchmark for improvements, it is good to know that a regulatory system similar to that of the EU could boost bilateral trade by 12 to 18% (De Groot et al. Reference De Groot, Linders, Rietveld and Subramanian2004). A positive example of economic effects of Croation’s EU enlargement and accession was shown in article of Lejour et al. (Reference Lejour, Mervar and Verweij2009). In addition, the implementation of European norms in Ukraine and Hungary provided an opportunity to enact reforms that promote development and enhance the quality of life for their citizens (Horbachenko et al. Reference Horbachenko, Tomina, Kotviakovskyi, Khominich and Smolenko2025).

National Quality Infrastructure in Serbia

Harmonizing national legislation with global partners is crucial for integrating national quality infrastructure into the global market, with EU agreements facilitating alignment with European standards (Qorraj et al., Reference Qorraj, Hajrullahu and Qehaja2024). Serbia’s quality infrastructure regulation comprises laws, ordinances, and rulebooks governing standardization, accreditation, metrology, and conformity assessment organizations (Ruso and Filipovic Reference Ruso and Filipovic2018). Adhering to European and international rules enables Serbia to join relevant organizations and become a full member of standardization bodies. The four NQI laws, including the Accreditation Law, Standardization Law, Metrology Law, and Law on Technical Requirements for Products and Conformity Assessment, incorporate solutions from the ‘New Legislative Framework’, enhancing trade in products (Ruso and Filipovic, Reference Ruso and Filipovic2020). Quality infrastructure encompasses standardization, metrology, conformity assessment, and accreditation, supporting sustainable development, effective operations, management, regulations, and international trade (Blind Reference Blind2024; Isharyadi and Kristiningrum Reference Isharyadi and Kristiningrum2021; Rab et al. Reference Rab, Yadav, Jaiswal, Haleem and Aswal2021). However, it challenges governments, requiring them to initiate and ensure that the system aligns with political objectives and international standards (Ruso and Filipovic Reference Ruso and Filipovic2020).

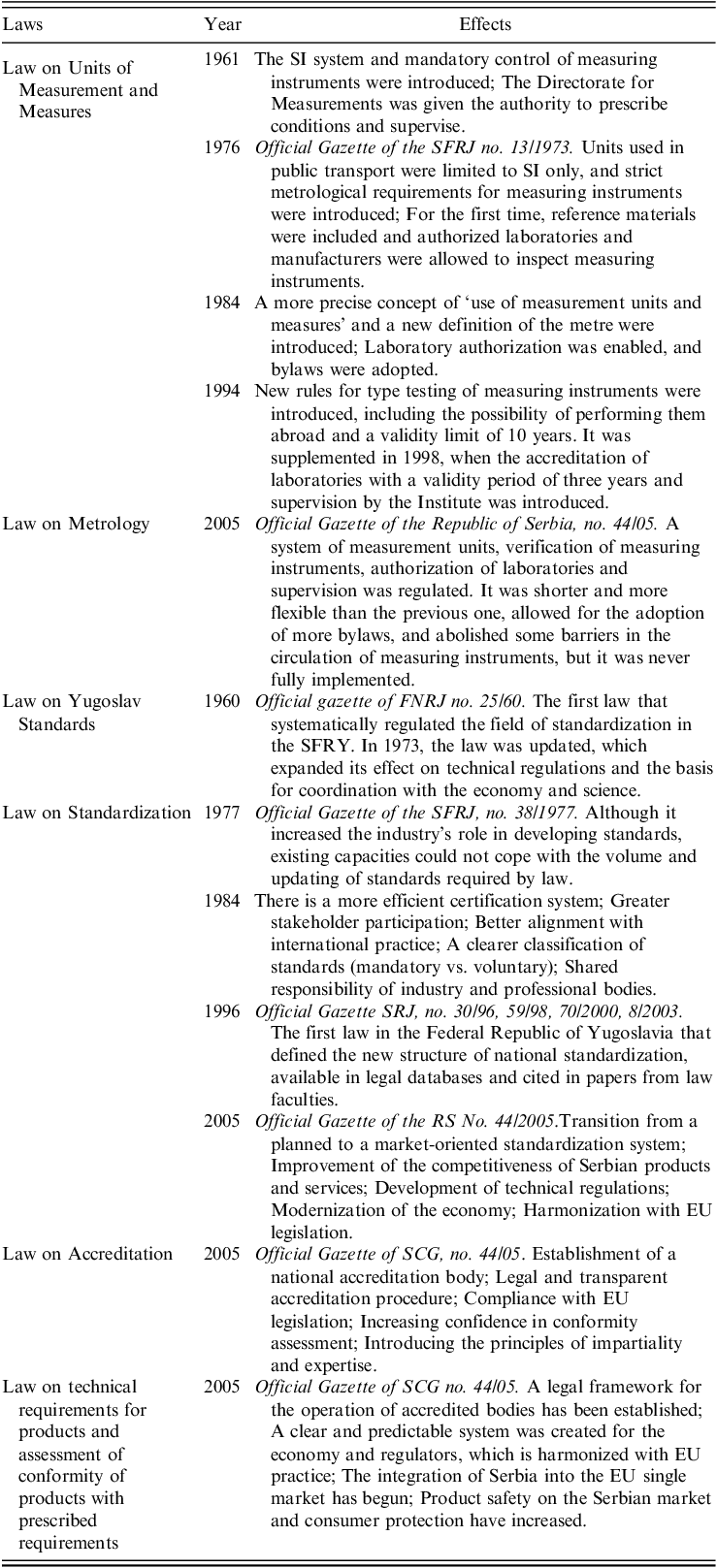

Prior to 2008, Serbia (as part of FR Yugoslavia and subsequently the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro) lacked a cohesive National Quality Infrastructure system that aligned with EU standards (Belić Reference Belić2023). Regulations on technical requirements and conformity assessment were regulated through several different laws and regulations. However, they were based on ‘old-regulatory approach’, i.e. they prescribed technical requirements for products in detail and did not apply the EU ‘new approach’ principle. When it comes to accreditation, there were no laws before 2005, but there were attempts to regulate accreditation through other acts and the formation of bodies. For example, in 1997, the government established the accreditation process based on its specific regulations (Jovanović Reference Jovanović2005). The first law that clearly and comprehensively regulated the field of accreditation in Serbia was adopted at the end of 2004 and began to be implemented in 2005. Finally, before 2008, there were laws in Serbia that regulated the field of metrology, but under different names and within a different legal framework (Belić Reference Belić2023). In 2008, the Government of the Republic of Serbia was formed by parties from the ‘For European Serbia’ list. So, the expansion of proposals and adopting laws in 2009 were expected and followed the ruling parties’ ideology. They offered the citizens a vision of ‘a better, more successful, modern, European Serbia’, and one of the basic principles of the ruling party in that period was inclusion in Europe, in which the party sees Serbia’s place. In this direction, since 2008, the Government of the Republic of Serbia has tried to harmonize as many laws as possible to open the door to the EU and achieve the then-set goal of joining the EU in 2014. Serbia officially applied for EU membership in 2009. On the way to European integration, Serbia is obliged to adopt over 22,000 European laws and regulations during the period of association and harmonization. Table 1 shows the chronology of the regulation of the QI laws before the need to fulfil the requirements for Serbia’s membership in the WTO and the EU.

Table 1. Regulation in the field of NQI before 2008 (authors’ contribution)

Methodology

In order to investigate the policymakers’ perception of national quality infrastructure, a qualitative method of analysing the content of parliamentary debates was applied. This method of content analysis is widely applied in political speeches (Rysicz-Szafraniec Reference Rysicz-Szafraniec2021) to analyse the visions, beliefs, and aspirations (Pitman Reference Pitman2012), preferences (Nefes Reference Nefes2022; Zvada Reference Zvada2022; Moilanen and Østbye Reference Moilanen and Østbye2021) and perceptions of policymakers or politicians (Morrison et al. Reference Morrison, Pons-Vigués, Díez E Pasarin, Salas-Nicás and Borrell2015). Qualitative content analysis goes deeper into the material and can reveal what is often lost in quantitative analyses, such as the meanings of metaphors or opinions (Bryman Reference Bryman2016). In addition, analysis of debates on the law topic is ‘revealing’ in terms of how quality is considered in a given democracy (Baker et al. 2015). Although interviews are a common qualitative method for exploring attitudes and perceptions (Wahyuddin Reference Wahyuddin2018), this research relied on parliamentary debates due to several practical and methodological advantages. Debates are publicly available, spontaneously expressed, and reflect views within the institutional context where NQI policies are formed. Unlike interviews, which can be influenced by bias or limited in scope, debate analysis offers a broader and more authentic perspective. Additionally, interviews with decision-makers posed challenges in terms of access and resources, while debates allow for observing changes in perceptions over time.

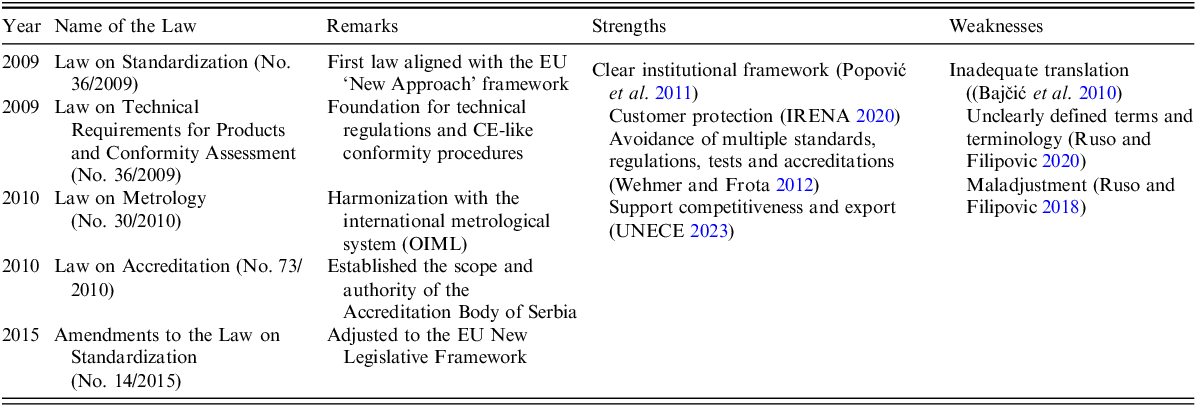

Following Serbia’s application for EU membership in 2009, there was a significant legislative overhaul, resulting in four key systemic laws between 2009 and 2010: the laws on Standardization, Technical Requirements, Metrology, and Accreditation. For analysis, data were generated in 2019 from open data sources, i.e. shorthand notes of the parliamentary debates of the Assembly from 2009 to 2015 (Table 2). The data source was the Open Parliament project website supported by the US Agency for International Development. As stated earlier, this time frame is considered because the largest number of harmonization of EU laws, as well as NQI laws, was implemented in 2009 and 2010. Later, amendments to the law were made with minor changes and without much discussion. Out of 266 speeches at the joint hearings, 35 speeches on NQI systemic laws were analysed in detail, including the speeches of law proponents, ministers, and deputies.

Table 2. Chronology of the adaptations of NQI laws in the Republic of Serbia 2009-2015

The specific research objective guided the selection of indicators in our model to explore how policymakers in Serbia perceive and debate laws related to the NQI. Given that the primary data source was plenary parliamentary debates, the indicators were derived inductively through qualitative content analysis of the most relevant and recurring themes: frequency and context of references to EU integration, quality-related terminology, technical concepts, and institutional roles. These indicators were chosen because they directly reflect policymakers’ awareness, understanding, and prioritization of NQI topics within legislative discourse.

As for the country selection, Serbia was chosen as a representative case study of a Central and Eastern European (CEE) country in EU pre-accession status. Serbia’s legislative path in the domain of NQI is particularly relevant due to its obligation to harmonize with over 22,000 EU laws and the fast-tracked adoption of technical legislation under the influence of accession requirements. Focusing on Serbia allows us to offer an in-depth analysis of the challenges and perceptions that other countries may share in similar transitional or accession processes. While this study is country-specific, the approach and findings offer a framework that can be replicated and compared across other CEE or developing countries undergoing similar legal and institutional transformations.

In order to better understand the results of the analysis of shorthand notes of parliamentary debates, it is necessary to explain all the steps in the legislative procedure in Serbia, i.e. the path of the law from the moment of initiation of the writing initiative to its entry into force. The policy proposal becomes official only after the government officially adopts it (Stančetić Reference Stančetić2013). This means that the government can choose one of the alternative policies without necessarily being the creator of that policy (Stančetić Reference Stančetić2013). Stančetić (Reference Stančetić2013) points out that only government representatives have the legally prescribed power to decide the official policy, while different participants can propose practical policy proposals. As Stančetić (Reference Stančetić2013) states, the adopted policy can be a decree, law, by-law, strategy, declaration or memorandum, and the most important decisions are made by the parliament, usually in the form of a law (Stančetić Reference Stančetić2013).

The Law on State Administration regulates law-making procedures in Serbia, which prescribes the methods and authorities involved in preparing draft laws and the conditions for holding parliamentary debates. Laws represent the most effective instrument of social regulation and the normative expression of a certain policy (Milovanović et al. Reference Milovanović, Nenadić and Todorić2012). According to the glossary of the Assembly (Glossary 2019), the law, as the main product of the parliamentary activity, is a written general legal act passed by the Assembly according to a special procedure that regulates the most important social relations. The legislative process in Serbia comprises eight stages:

-

1. Initiation: Any member of parliament, the government, the Assembly of an autonomous province, or at least 30,000 voters, the National Bank of Serbia, or the Ombudsman can propose a law.

-

2. Appointment: A body is appointed to draft the law as individuals or by forming a working group.

-

3. Preparation: Individuals or working groups prepare the working version of the law.

-

4. Adoption (Working Version): The relevant ministry adopts the working version, creating the draft law.

-

5. Parliamentary Discussion: The draft law is discussed in parliament based on the working version or draft.

-

6. Government Adoption: The government adopts the draft law, determining the proposed law.

-

7. Assembly Analysis: The bill is presented to the Assembly and analysed by deputies, including discussions and amendments in committees.

-

8. Plenary Discussion and Voting: The proposed law undergoes plenary discussion and voting, becoming a valid regulation once approved.

For the planned analysis of amendments and discussions on laws that are in any way related to quality infrastructure laws, the fifth, seventh and eighth phases are the topics of interest in this paper. After the law has been discussed in the committees, the bill with amendments is presented at the Assembly’s plenary session. Then, parliamentary groups conduct the discussion according to the predetermined order of presentation. First, there is a general debate on the proposed law, then a debate on details (amendments) and finally, on the whole.

Before explaining the role of amendments in the law-making process, it is essential to explain the principled discussion and the detailed and comprehensive discussion to analyse the parliamentary discussion in the Assembly. According to the brochure entitled ‘The Way of the Law’ and the Rules of Procedure of the Assembly of Serbia, ‘the procedure for consideration and adoption of a bill in the Assembly begins with a preliminary hearing’. Deputies discuss the proposed law, considering its necessity and underlying principles. Before the Assembly session, the relevant committee holds a preliminary hearing. If the committee and government recommend acceptance, they must specify any proposed amendments. Detailed debate follows, examining each article with proposed amendments. The competent committee conducts a similar detailed examination. Finally, a voting day is scheduled for the law as a whole.

Results

The largest number of adopted laws was in 2009 and 2010 (Smigic et al., Reference Smigic, Rajkovic, Djekic and Tomic2015), and the agenda of the Assembly most often contained proposals for laws from the so-called ‘European agenda’. According to the report of the SeConS (2013) project, from 11 June 2008, to 13 March 2012, the Assembly performed legislative activity for a total of 453 days in regular and extraordinary sessions. As a result, 807 laws and 217 other acts were passed, and 22,251 amendments were submitted and discussed. Following data from the official website of the Assembly (NSRS 2018b), the first systemic national quality infrastructure laws in the Republic of Serbia (the Law on Standardization and the Law on Technical Requirements for Products and Conformity Assessment) were adopted in 2009. The Assembly held 30 sessions for 164 days in the same year with 328 items on the agenda. The number of submitted bills was 316. The total number of submitted amendments was 11,923 from the government (70), the Assembly committees (210), deputies (11635) and others (eight). In 2010, the total number of sessions held was 21, of which the number of submitted bills was 207, and amendments totalled 4,096, of which: Government (59), committees of the Assembly (157), deputies (3874) and others (six). In the same year, the Law on Metrology and the Law on Accreditation were adopted. In the following, the activities of the policymakers in the parliament in 2009 and 2010 were analysed, starting from the content of the agenda to the shorthand notes of the parliamentary debates on quality infrastructure laws. Out of the total deputies present, most voted to adopt the attached quality infrastructure laws.

Laws and Translation Challenges

In the regulation entitled Unique Methodological Rules for Writing Laws, it is written that anyone who proposes a law and is authorized by the Constitution as a proposer is obliged to use the Serbian language and words that exist in the Serbian language for the terminology that is foreseen and used by law. However, according to the opposition’s opinion, this was not the case when the laws related to quality infrastructure were written and translated. By analysing the records of parliamentary debates, criticisms of MPs about vague terms and translations were noticed (Appendix I-1). When it comes to language barriers, Ćirić (Reference Ćirić2009), in his paper ‘Adaptation and implementation of the EU - Acquis: exchange of experience’, pointed out the problem of mechanical adoption of laws that Serbia had when translating documents into the Serbian language, due to the lack of qualified people who would work on translations and had minimal knowledge of laws and regulations. Several MPs also proposed language changes in the parliamentary debates (Appendix I-11).

Law and Conceptual Misunderstandings

Members of the Parliament proposed changing the name of the Law on Accreditation to the Law on Quality Control of Products and Services, as well as the name of the institution - Accreditation Body to the Quality Control Agency. The proposals to change the name of the Accreditation Body and the law indicate that policymakers may not fully grasp this institution’s underlying concepts or functions.

Laws and Agenda Settings

Considering the agenda of quality infrastructure laws, an illogicality was observed in unifying the discussions. Namely, the Law on Metrology was on the agenda, along with the Law on the Right to Free Shares, the Law on Privatization, and the Law on Regional Development. Also, the Law on Tourism has been merged with the Law on Standardization, the Law on Technical Requirements for Products and Conformity Assessment, and the Law on Foreign Trade. MPs in the Assembly also noticed this illogicality when the Law on Metrology was on the agenda. The following statements of MPs support these occurrences (Appendi I-2). Another surprise regarding (dis)relatedness and several laws is the new Law on Metrology from 2016, which was on the agenda with 13 other laws. The opposition MPs’ comments on the agenda are given in Appendix I-3. Within the same agenda, the number of speaking engagements on the NQI law is significantly lower than the others (35 out of 226 speeches). The limited time for discussion often leaves little room for preparation and comments by policymakers. The following comments of the MP in Appendix I-4 support this claim.

Laws and Time Limitations

In 2006, an expert of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe stated in his report on analysing the Assembly’s rules of procedure (COE 2015) that the time for discussion on a bill is minimal. He states that considering the allotted time for parliamentary groups, the number of parliamentary groups, and the number of mandates, there may be very little space for discussion on a particular law, primarily if a joint debate is held on several draft laws simultaneously. Moreover, as a rule, MPs do not know in what order and dynamics the government will submit legislative proposals. For this reason, they cannot adequately prepare for discussions. In addition to all that, there is the belief that the agenda is often not submitted on time, which is confirmed by the following statements of the deputies in Appendix I-5.

Many laws were taken from EU legislation, which left little room for adapting them to Serbia’s specifics because it was considered that something that already works in European practice should not be challenged. The statement in Appendix I-6 supports this law copy phenomenon.

Law and Fast-track Procedure

Furthermore, in communication with the professional public, the problem of the speed of passing laws arises. MPs are often physically unable to read the legislative proposal in detail, analyse it and consult with experts, or read some relevant professional or scientific analyses. Another proof of adaptation to the EU is that the Law on Accreditation was adopted under an urgent procedure (Appendix I-9). The assembly prescribes that a law can be passed under an urgent procedure representing the fulfilment of international obligations and harmonization of regulations with EU regulations. According to shorthand notes from the website of the Open Parliament, the statement of one of the MPs of the opposition reads about the enormous speed of passing laws (Appendix I-10).

Legislation as an EU Obligation

The demotivating factor for working on laws is the agenda of joining the European Union. Many laws are transferred from the legislation of EU member states, and according to the MPs, there is no room for improvements or changes. Consequently, both the law proposers and the ruling parties’ representatives first emphasize the importance of adopting these laws as a condition for entry into the WTO and the EU, and only then point to the positive effects. Statements by MPs in parliamentary debates on quality infrastructure laws also confirm this fact (Appendix I-7). However, the representative of the ruling party himself mentioned in his presentation that the need to pass this law on accreditation was imposed (Appendix I-8).

Finally, after reviewing the parliamentary debates on the four quality infrastructure laws, it is also noticed that policymakers often use the debate space to attack the Government (legislators and ministers) and call out current topics unrelated to the given topic of discussion.

Discussion

Stojiljković (Reference Stojiljković, Pavlović and Orlović2007) views MPs as mere puppets of their parties, obeying instructions from party leaders and economic elites who make crucial decisions. Similarly, Jordan and Richardson (Reference Jordan and Richardson1987) characterize parliament as a superficial display. In contrast, Krehbiel (Reference Krehbiel2010) argues that meaningful contribution to legislation necessitates the right to propose bills, engage in debate on content and consequences, offer amendments, and negotiate compromises. Policymakers’ capacity to identify flaws in existing laws often drives the need for amendments. However, the results of this research are closer to the opinions of Stojiljković (Reference Stojiljković, Pavlović and Orlović2007) and Krehbiel (Reference Krehbiel2010).

After analysis of shorthand notes, the results showed that MPs first noticed a problem in translation when taking over the EU quality infrastructure law. This phenomenon is known in the literature as ‘Europeanization of legal terminology’, where the practice of incorporating legal borrowings or adaptations from various European languages into the languages of EU member states is a common characteristic of EU law terminology (Kordić Reference Kordić2023). To improve the practicality of this issue, it could be proposed that a national bilingual terminology framework be developed (Kudashev Reference Kudashev2013), along with targeted training programmes (Al-Tarawneh et al. Reference Al-Tarawneh, Al-Badawi and Hatab2024). Additionally, implementing a process for ex ante legislative assessments that includes quality improvement specialists would help ensure accuracy in terminology and coherence in policy (Prieto Ramos and Cerutti Reference Prieto Ramos and Cerutti2021; Costa et al. Reference Costa, Silva and Soares de Almeida2012).

One of the proposals of MPs was to change the name of the law related to accreditation, where the proposal clearly shows a lack of understanding professional terminologies such as quality control and accreditation. Product quality control is typically conducted within organizations that manufacture goods or provide services, suggesting a misunderstanding of quality infrastructure concepts. Williams (Reference Williams2001) attributes this to a lack of familiarity with technical terminology or insufficient information and specialized knowledge. Moreover, the urgent adoption of the Accreditation Law may limit policymakers’ preparation time for the debate. Another ignorance of terminology and difficulties in translation is seen in suggesting that MPs replace the word ‘accreditation’ with ‘accreditation procedure’. In this case, it would be a pleonasm. Accreditation is a procedure that helps the entire process of confirming competence become reliable and transparent (Harmes-Liedtke and Matta Reference Harmes-Liedtke and Matta2021). A similar conclusion is found in the report ‘How do MPs make decisions?’ (SeConS 2013) from the Open Parliament project. It discusses challenges encountered by MPs when writing and proposing amendments. The research highlights several difficulties, including MPs’ lack of expertise in relevant professional and legal legislation matters. This often leads to misusing terms in amendments and debates, as well as misunderstandings or insufficient information (SeConS 2013).

Based on the Rules of Procedure of the Assembly, when determining the agenda, the Assembly decides to combine discussions within the same agenda. Such joint discussions are provided for in Article 140, paragraph 2 of the Rules of Procedure (2009) when several draft laws are on the agenda of the same session, and they are mutually conditioned, or their solutions are interconnected. Considering the agenda that included quality infrastructure laws, an illogicality was observed in combining the laws discussions. These statements of MPs are also confirmed by the research of the Open Parliament (Reference Parliament2013), in which it was established that the Government proposes, and the Parliament passes many laws, especially those that are part of the EU accession agenda. For this reason, debates at the plenum are often condensed and include several items on the agenda, and deputies do not have enough time to discuss each law in detail.

The results showed that the number of speaking engagements focused on the NQI law is considerably fewer compared with the others within the same agenda. The low interest of MPs and the unification of discussions within one agenda item, the solutions of which are not mutually conditional, have made quality infrastructure laws second-rate. Research conducted in Serbia by Vuković (Reference Vuković2013), based on the answers of individual MPs, clearly indicates that key political decisions, as well as concrete solutions in the domain of law and public policy, are made at party bodies and in negotiations between parties that are members of the ruling coalition. After such results, the thought arises that the goal of policymakers is to unconditionally adopt laws for the sake of integration and access to the EU and the WTO (Mendelski Reference Mendelski2015; Vidačak and Škrabalo Reference Vidačak and Škrabalo2014) by drawing attention to more ‘priority’ laws and topics. Vuković (Reference Vuković2013) claims that certain laws will be discussed at party bodies, depending on how much the party itself is interested in the law. Vuković (Reference Vuković2013: 77) believes that ‘If the relevant minister comes from the ranks of that party, then he would be more interested in dealing with the bill.’

MPs also noted issues such as limited debate time, unclear scheduling of legislative proposals, and delayed agendas hinder MPs’ ability to prepare and engage effectively in parliamentary discussions, especially during joint debates on multiple draft laws. Perhaps this is another way to unconditionally adopt EU laws, which prevents preparations for discussion and objections. The fact that the laws regulating different areas accumulate within one discussion and that the agenda is often unavailable consequently leads to the problem of maniacal adoption of laws, not providing enough space for interpretation. However, what can start a new discussion is that the MPs may be aware of their powerlessness in the process of legislative harmonization, so they give up the discussion, not wanting to waste words and time. Consequently, policymakers take uncompromising decisions on the adoption of laws. Therefore, such a comment clearly shows that the MP does not understand that the Republic of Serbia is not the same as other EU members, thereby confirming the mechanism of the ‘flow boiler’. Furthermore, this lack of critical review of the national economy, culture, language and available resources indicates a phenomenon known as the ‘nodding approval’ phenomenon.

MPs’ statements in parliamentary debates on QI laws reveal that the EU accession agenda can be a demotivating factor, as laws are largely transferred from EU member states with little room for adjustment, leading proponents to prioritize alignment with EU and WTO requirements over emphasizing potential national benefits. Through these statements, we can see that most speakers emphasize that quality infrastructure laws are necessary for accession, membership and admission to the WTO and the EU and the continuation of reforms on the way to the EU. In other words, one gets the impression that natural pressure is exerted on the decision-makers regarding adopting these laws because the EU and the world market are primacy over the domestic market, consumer protection and product safety in Serbia.

Further, the fast-track procedure was a dominant phenomenon during the EU law harmonization in Serbia. However, the large number of laws adopted by urgent procedures reduces the democratic potential of policymakers and makes it impossible for them to deal with such laws in detail. If the law is extensive, and the deputy is not from that field, he or she needs time to consult with experts to understand the matter better and prepare for the debate. The urgent procedure does not allow this because the deputies have only 24 hours to prepare, provided that they have learned that this law is on the agenda, which is often not the case. It should also be considered that the urgent procedure may allude to the intention of the proposer to quickly ‘slide’ something through the legislature without significant discussion. This observation was recognized by Walsh (Reference Walsh2013) and Rommetvedt (Reference Rommetvedt, Zajc and Langhelle2009). In such cases, as the comparative analysis of the countries of CEE showed, we can freely state that the legislative body of the Republic of Serbia works according to the system of ‘flow boiler’ or ‘well-oiled machine’ – a situation in which the process of adopting laws takes place quickly, automatically and without substantial discussion – almost mechanically (Wright Reference Wright2013; Korkut Reference Korkut2010).

Finally, after examining the parliamentary discussions regarding the four NQI laws, it is evident that policymakers frequently utilize these debate sessions to criticize the Government (including legislators and ministers) and to raise issues unrelated to the topic at hand. This tendency suggests either a diminished interest in or a lack of understanding of the significance of quality infrastructure legislation. Similarly, Akirav (Reference Akirav2014) found in his study that legislators often use One-Minute Speeches as a means to promote their policies within parliament. His findings indicated that these public speeches typically focus on critiquing current policies while proposing alternatives.

All these point to the formal satisfaction of administrative priorities, ignoring their very essence. In this way, the adaptation of European legislation to minor legal practice follows the path in which the European legal acquis follows the preferences and experiences of Western European countries, often neglecting and overlooking the characteristics of the environment to which it has yet to be applied (Nadazdin-Defterdarevic Reference Nadazdin-Defterdarevic2015). Consequently, it can result in a poor understanding of laws, significantly complicating their application in practice, especially for economic entities and consumers. Koutalakis (Reference Koutalakis2010) highlighted business actors as a crucial force in the process of legal and policy harmonization in the pre-accession negotiations phase. However, dimension is rarely analysed in the framework of public policies. Although laws are often formally harmonized with EU regulations, without clear communication and institutional preparations they remain ineffective or incorrectly applied. Dimitrova (Reference Dimitrova2002) points to the problem of formal adoption without actual implementation, while OECD (2018) and Scott (Reference Scott, Jordana and Levi-Faur2004) emphasize the importance of comprehensibility and the broader institutional context for the successful implementation of regulations. Incomprehensible laws lose their normative force and undermine trust in institutions.

The extensive legislative activity in 2009 and 2010, characterized by the rapid adoption of numerous laws, was largely influenced by external economic factors, particularly the need to align with EU and WTO standards. While this effort aimed for Serbia’s long-term integration into global economic systems, it resulted in some adverse effects on the real sector. Many of the enacted laws were complex, difficult to understand, and inadequately tailored to local economic conditions, making implementation challenging for small and medium-sized enterprises, which are crucial to the Serbian economy. Reports from chambers of commerce and professional associations indicate that legal uncertainty and the rapid pace of regulatory changes significantly hinder the business environment and investment confidence in Serbia (NALED 2017; World Bank 2020).

Moreover, the lack of effective analyses before implementing laws has led to regulatory fatigue among those expected to enforce them, including state administrations, local governments, and businesses. In terms of quality infrastructure, this is evident in the high costs associated with certification and accreditation for companies that were not adequately informed or involved in the law-making process. Parliamentary debates reveal that even political leaders often lacked a full understanding of the laws’ functions and economic rationale, complicating their real-world application. This creates an impression of legal and institutional instability that may deter foreign investors and hinder the growth of industries reliant on standardization, metrology, and accreditation.

Conclusion

This article emphasises the crucial role of a well-established national quality infrastructure in facilitating world trade, enhancing market access, improving competitiveness, ensuring product safety, and fostering consumer confidence. It underscores that functional quality infrastructure is essential for accessing regional and global markets and is vital to a country’s competitive advantage. The article highlights the responsibility of policymakers in formulating, selecting, and implementing policies to achieve these objectives. Its primary focus is to offer insight into the state of policy creation in Serbia’s quality infrastructure sector during the adoption of the NQI law.

The analysis of parliamentary debates regarding laws related to NQI reveals that aligning legislation with the EU’s legal framework faced several structural and procedural challenges. During significant legislative activity, particularly in 2009 and 2010, laws were often adopted rapidly under the ‘European agenda’. This accelerated approach frequently resulted in inadequate linguistic and conceptual adjustments to fit the domestic legal and institutional context.

Shorthand notes from parliamentary debates in the Parliament of Serbia regarding four technical laws on quality infrastructure were analysed. The analysis revealed that European solutions were hastily and mechanically adopted without sufficient room for compromise or critical evaluation of their applicability in Serbia due to time constraints, a crowded legislative agenda, opaque agenda presentation, poor translations, and insufficient comprehension of concepts. This rushed adoption, especially common in developing countries, risks incurring unjustified economic and social costs. Furthermore, the quality infrastructure laws were swiftly approved without public discussion, and the Accreditation Law was passed under emergency procedures. These observations indicate that the quality infrastructure laws were perceived merely as EU requirements imposed on Serbia rather than recognized as necessities with intrinsic value and relevance.

It was established that some policymakers who explained and defended their party’s personal views in detail in parliamentary debates did not adequately understand the concepts of NQI. Also, one cannot fail to state that policymakers often use the time for discussions to criticize the current government, which is unrelated to the aforementioned laws in terms of content. It was observed that the number of MPs who appeared on the floor was significantly higher than the ranks of the opposition, which can be explained by the favourable opportunity for speaking on various grounds.

This situation can negatively affect the economy, health, safety, and protection of consumers and the environment in the common market. Policymakers’ inadequate perception can lead to wrong decisions, which consequently stifle innovation, create barriers to trade, and risk product safety. Therefore, it can be concluded that the role of policymakers in creating quality infrastructure is of national importance for all stakeholders, emphasising the role of the end-user-citizens. In addition, the discussions in the parliament often served for political contests, and not for substantive discussion of the laws, which further can undermine the quality of adopted solutions and their applicability in practice, especially in the domain of economy and consumer protection.

Future studies could examine the real-world effects of quality infrastructure legislation at the local level, considering the perspectives of both the public and decision-makers. It’s important to consider additional elements that influence political decision-making, and the challenges faced during the implementation of these laws. An analysis of how institutions and businesses understand and enact these laws in practice would be beneficial, as well as comparing Serbia’s experience with that of other CEE countries pursuing EU accession after the analysed period. Lastly, integrating discourse analysis with interviews or surveys would enhance our understanding of the law-making and enforcement processes. While using parliamentary debates is insightful, reliance on this single source can limit the depth of analysis. Hence, the triangulation method can include broader stakeholder input (e.g., industry experts, civil society) and would provide a more comprehensive perspective. Additionally, the availability and quality of meeting minutes may vary, potentially affecting the scope and accuracy of the analysis. Finally, the analysis is time-limited to a period of intense legislative activity, and the results are not necessarily generalizable to later stages of the European integration process. Also, it should be borne in mind that parliamentary discussions often do not reflect the entire decision-making process, given that a significant part of the process (e.g. negotiations, adjustments, political agreements) takes place outside plenary sessions and without public control.

The outcomes of this study are pertinent for countries that are in the process of joining the EU and can serve as a valuable tool for policymakers tackling challenges in developing a legislative framework for NQI. The findings highlight the necessity for increased engagement from professionals in the law-making process, as well as the importance of recognizing local contexts when aligning with European regulations. Furthermore, this research can help raise awareness in Serbia and other CEE nations regarding the significance of parliamentary discussions in creating effective quality infrastructure and the need to enhance institutional capacities for interpreting, understanding, and implementing intricate technical regulations. Additionally, the findings prompt a reassessment of how European laws are integrated into national legal systems, aiming to ensure formal compliance and practical effectiveness.

Appendix

Jelena Ruso is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Quality Management and Standardization at the Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade, Serbia. She earned her BSc, MSc, and PhD from the same University and Faculty. Her research interests include quality infrastructure, quality management, standardization, metrology, accreditation, and certification.

Jovan Filipovic is a Quality Management Professor and Head of the Department of Quality Management and Standardization at the University of Belgrade, Faculty of Organizational Sciences. He earned his PhD and MSME from Purdue University (USA) School of Mechanical Engineering and BSME from Belgrade University School of Mechanical Engineering. He also earned another PhD from the University of Ljubljana (Slovenia), Faculty of Public Administration. His research interests include quality infrastructure, public administration, quality management, standardization, metrology, accreditation, and certification.