Do populist governments respond to market pressure against their economic policies, particularly those involving sovereign finance, and, if so, to what type of investors do they respond? Over the past three decades, populist parties have become increasingly successful electorally, in some cases becoming formal coalition partners in government or informal partners through confidence-and-supply arrangements. On rarer occasions, populist parties have commanded full control over government, granting them authority to dictate national policy.

Yet when populist parties control government, even with few institutional checks against them, they are subject to a constraint that they could conveniently ignore while serving in opposition: the influence of financial markets. Bond investors are gatekeepers of sovereign finance, which can grant them considerable sway over governments’ economic policies. A large literature in international political economy (IPE) explains why market actors have accumulated such power over sovereigns over the past five decades. As governments increasingly rely on borrowed funds, there is greater pressure for them to shape their fiscal and monetary policies around the preferences of bondholders (Andrews Reference Andrews1994; Cohen Reference Cohen, Gilbert and Helleiner1999; Kaplan and Thomsson Reference Kaplan and Thomsson2017; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2011; Strange Reference Strange1996; Streeck Reference Streeck2014). Much of this “market discipline hypothesis”Footnote 1 literature has focused on governments of mainstream parties, whose more pragmatic approach to governing has proven malleable to the concerns of market actors, particularly during times of financial panic.

In this article, we ask whether populist governments are similarly likely to bend to market pressure when investors raise concerns over their macroeconomic policies and, if they are, which type of actors are most effective in forcing government U-turns. Populist governments on both the left and right of the political spectrum should be more resistant to market pressure than mainstream parties for three reasons. First, their political modus operandi scapegoats elites, including financial and economic elites, as enemies of the people and the nation (Halikiopoulou, Reference Halikiopoulou2018; Mudde Reference Mudde2010). Second, economic malaise intensifies political support for populists (Hopkin Reference Hopkin2020). Given that populist governments champion “the people” who have been “left behind,” one would expect them to prioritize their interests over investors, particularly if these investors are foreign bondholders. Reversing course on headline policies in response to the behavior of market actors would signal the weakening and subordination of their populist policies, potentially delegitimizing their rule.

Third, a more recent literature on financial and economic nationalism (Da Silva Reference Da Silva2023; Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015; Reference Johnson and Barnes2025; Oellerich and Bohle Reference Oellerich and Bohle2024) highlights that once populists come to power, they often attempt to reengineer financial markets to reduce the influence of foreign investors and trap domestic investors (and central banks) into supporting their sovereign financing needs. Recent work has empirically documented that bond markets negatively react to far-right populists entering government (Johnston Reference Johnston2024), yet anecdotal evidence reveals that populist governments have a mixed track record in responding to market pressure by changing their policies. Some cave to market panic. For instance, Giorgia Meloni diluted her proposed windfall tax on bank profits once bank shares tumbled in Italian stock markets after the tax’s announcement (Kazmin Reference Kazmin2023). But others remain defiant, even when populist policies result in significant and prolonged economic self-harm. The populist Euroskeptic wing of the UK Conservative Party ensured Brexit was brought to fruition, even though it considerably weakened the value of the pound, the UK’s credit rating, and the country’s long-term growth prospects.

Using a most-different case study design of the populist Five Star Movement (M5S)/Lega coalition in Italy and Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz government in Hungary, we find that populists do bend to market pressure, but that this market-disciplining effect does not stem primarily from foreign investors and their threats of exit. Although governments in both countries repeatedly defied and chastised foreign investors (and in the case of Hungary, orchestrated a reduction in the influence of foreign investors through deliberate financial subordination), it was the power of domestic investors that caused these governments to reverse course on headline policies. In Italy, the M5S/Lega coalition substantially altered its “People’s Budget”—cutting €7 billion from M5S’s citizens’ income policy and abandoning both parties’ electoral promises to repeal cost-saving pension reforms made by prior governments—not in response to threats from the European Commission about the launch of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP) or foreign capital flight but rather after demand for Italian bonds from domestic investors collapsed in the November 22, 2018, BTP Italia bond auction. In Hungary, domestic bondholders’ increasing reluctance to finance the government in the face of high inflation in 2022 forced the Orbán government to renege on major election spending commitments and to compromise with EU demands on rule-of-law targets and financing for Ukraine. In other words, it was not the actions of footloose foreign investors that led to policy reversal but rather the “bowing out” of domestic investors with a vested interest in the sovereign’s solvency. Because domestic investors served as both governments’ bond “buyers of last resort,” these governments needed to maintain their favor to be able to borrow.

Our article proceeds as follows. The next two sections briefly review the IPE literature on the market discipline hypothesis and the structural power of foreign investors, as well as the recent comparative political economy (CPE) literature on the economic policies of populist governments. We then theorize under what conditions populists might bend to market discipline. Next, we present our case studies and demonstrate that, despite the considerable economic and political differences both governments faced, both the M5S/Lega coalition and the Orbán government were similarly pressured by domestic investors to alter key components of their policy agendas. We conclude with a discussion of how our findings speak to broader debates on the disciplining power of capital and the malleability of populist governments’ policy agendas.

Market Constraints on Government Autonomy: Are Financial Investors All Powerful?

Financial liberalization and the removal of capital controls since the 1980s have considerably increased the power of capital. As governments turned to financing deficits via borrowing rather than through taxation, they became pressured to orient their policies to the preferences of their investors, even if those were at odds with what voters preferred (Cohen Reference Cohen, Gilbert and Helleiner1999, 126). The logic behind this market discipline hypothesis is straightforward. As the ease of buying and selling bonds increases, fickle bondholders can shed assets that they perceive to conflict with their appetite for risk. If governments pursue policies perceived as inflationary or deficit prone (even though those policies might be electorally popular), bondholders may move the bonds of these sovereigns out of their portfolios, reducing demand and increasing yields. Hence, it is in governments’ interests not to deviate too much from what their bond investors want in order to safeguard their access to borrowing and limit rises in debt-servicing costs (Andrews Reference Andrews1994; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2011; Strange Reference Strange1996; Streeck Reference Streeck2014).Footnote 2

Others doubt whether global investors can constrain the actions of governments so easily. IPE scholars highlighted that international bond investors did not necessarily “cut and run” in response to worrisome political developments such as the election of left governments that advocated expansionary spending policies and greater state intervention, even in developing countries where financial market constraints are arguably stronger. When examining market reaction to the electoral successes of the left populist Lula da Silva in Brazil, for example, both Hardie (Reference Hardie2006) and Jensen and Schmith (Reference Jensen and Schmith2005) noted that international bond investors increased their holdings of Brazilian bonds after Lula’s electoral victory and that average returns on the Brazilian stock market were largely unchanged. Brooks, Cunha, and Mosley (Reference Brooks, Cunha and Mosley2022) similarly find that although (left) government partisanship affects volatility in bond spreads, it does not affect the average risk premia within them. Mosley, Paniagua, and Wibbels (Reference Mosley, Paniagua and Wibbels2020) show that country-specific factors have no impact on sovereign spreads after accounting for global financial market conditions like changes in liquidity.

One possible reason why empirical evidence supporting the market discipline hypothesis remains inconclusive is because this hypothesis does not fully account for who is investing in government bonds. A large literature on the structural power of finance has revealed that investors’ appetites for risk and returns are hardly uniform. Distinctions have been made in the risk appetites of different types of “bond vigilantes,” particularly regarding their domicile. Foreign investors are perceived to be more fickle than domestic investors because they face lower exit costs, demonstrate less “loyalty” to a sovereign, and hence are less likely to become a captive audience to the economic policies of governments whose bonds they hold (Cohen Reference Cohen, Gilbert and Helleiner1999; Rommerskirchen Reference Rommerskirchen2020, 5). Consequently, foreign investors often place sharper constraints on sovereigns’ policy choices through threats of capital flight and the cessation of new funding than do their domestic counterparts.

However, not all governments are so beholden to foreign bondholders. Domestic investors tend to be more patient than their foreign counterparts and have proven more willing to hold their governments’ bonds, even throughout times of economic turmoil and uncertainty (Andritzky Reference Andritzky2012; Kurzer Reference Kurzer1993). Kaplan and Thomsson (Reference Kaplan and Thomsson2017) highlight that domestic banks, in particular, have incentives to be patient with their governments, because their deep exposure to sovereign debt directly links their profitability to the government’s financial health. Through their reliance on domestic markets whose health is also linked to government solvency, domestic investors become a captive audience to governments, weakening their structural power (Culpepper and Reinke Reference Culpepper and Reinke2014).Footnote 3 Domestic and “dependent” investors, in other words, loosen the constraint of market discipline and provide governments with greater “room to move” on their fiscal policies, even when their borrowing costs rise.Footnote 4

Liberal Markets Meet Illiberal Politics: Investor Discipline in a Least Likely Case?

Most IPE scholars working on the politics–market nexus assume that governments care about market reactions and hence should respond to market pressure if it arises. But despite a vast literature that has examined how market actors evaluate governments and their policies, fewer studies document whether governments actually respond to market discipline. Rommerskirchen (Reference Rommerskirchen2015; Reference Rommerskirchen2020) and Johnston and Barta (Reference Johnston and Barta2023) found that governments do respond to market pressure, but those responses are heavily dependent on context. Rommerskirchen found that “market punishment” only caused governments to engage in austerity if they were within the Eurozone, presumably because of their exposure to the European debt crisis, (Reference Rommerskirchen2015) or if they had large foreign investor bases (Reference Rommerskirchen2020). Johnston and Barta (Reference Johnston and Barta2023) found that government responsiveness to downgrades from credit rating agencies only emerged after the 2008 global financial crisis, and, at least in the long run, was largely limited to highly indebted countries. Yet these works focus on governments led by mainstream parties, who are cognizant of the consequences of market panic because they (may) have had experience in managing public policy during times of economic/financial crisis.

Might populist governments react differently to the demands of bondholders? Before the past two decades, most populist parties enjoyed the privilege of serving in opposition, avoiding the costs of governing. Hence, they could advocate unconventional (and untested) economic policies that were unlikely to come to fruition. As these parties enter power, populists potentially encounter a Faustian bargain with markets. Populist parties must decide whether to betray their supporters and abandon policies that markets dislike to preserve privileged access to sovereign borrowing or to defy the preferences of investors at the expense of higher borrowing costs. Succumbing to market pressure, especially if it involves a reversal in policies demanded by their base, should be particularly harmful to the legitimacy of populist governments. Not only would it make these “strongmen” appear feeble but they would also appear beholden to the very elites they publicly scorn.

In contrast to their mainstream party counterparts, we expect populist governments to discount the concerns of investors over the demands of their voters. Populism has emerged in part as a reaction to economic anxiety generated by the inequalities and (geographical) disparities that advanced stages of capitalism have unleashed on electorates (Bolet Reference Bolet2020; Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2019; Hopkin Reference Hopkin2020). Although populist parties have emerged on the left and right of the political spectrum, they have a common denominator of nationalism and (for those in Europe) Euroskepticism. Halikiopoulou, Nanou, and Vasilopoulou (Reference Halikiopoulou, Nanou and Vasilopoulou2012) highlight that both left and right populists promise to challenge (and remove) external threats to the people, although they diverge on the nature of these external threats. Within Europe, left and right populists have a common adversary in the European Union; the populist left perceives the EU as an imperial neoliberal project that threatens the policy autonomy of the nation, whereas the populist right perceives it and its policy interventions as a threat to the cultural homogeneity of the nation (508–9). Because they represent the interests of those who have been left behind socially and economically, populist parties tend to champion policies—trade protectionism, economic nationalism, and welfare chauvinism—that refute neoliberalism (Johnston Reference Johnston2024; Rathgeb Reference Rathgeb2024).Footnote 5 Foreign investors should draw particular ire from populist governments, given their elite and non-native status.

All democratic governments face a tension between (fiscal) responsibility and (electoral) responsiveness while governing. We predict that populist governments would favor responsiveness over responsibility when encountering market discipline for two reasons. One is the specific pressures that come with placating their political base. On ideology, voters for populist parties are not as wedded to the doctrine of free markets as voters of more centrist parties but instead are more supportive of an authoritarian and interventionist state. Populist voters in Europe, crucially those who support the nationalist far right, support trade protectionism (van der Waal and de Koster Reference Van der Waal and de Koster2018) and a “chauvinist” welfare state that provides generous social consumption for natives, particularly for the elderly and children (see Busemeyer, Rathgeb, and Sahm Reference Busemeyer, Rathgeb and Alexander2022). The economic policy positions of populist far-right parties reflect these voter preferences (Fenger Reference Fenger2018; Johnston Reference Johnston2024, 9; Rathgeb Reference Rathgeb2024; Toplišek Reference Toplišek2020).Footnote 6 Because their voters are openly hostile to financial elites, we expect that populist governments will similarly be hostile to market discipline, especially if discipline is strongly influenced by the behavior of foreign investors.Footnote 7 On governing, populist supporters are distinctively anti-establishment and hence may scorn any political compromise with mainstream economic and political actors. In opposition, populist parties can capitalize on such voter dissatisfaction, but once they come into power they are more vulnerable.Footnote 8 Incentives to avoid compromise and stay the course on promised headline policies will be particularly acute for salient distributive economic issues, what Culpepper (Reference Culpepper2010, xv) calls “the stuff on which elections are won and lost.”

Second, populist governments may also deflect market pressure institutionally by implementing financial nationalist policies that reduce the influence of foreign investors and (external) financial liberalization. Financial nationalism, a subtype of economic nationalism, represents a worldview that is nationalist in its motivation for political action, financial in its policy focus, and illiberal in its conception of political economy (Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2025). Financial nationalists identify the use and control of central and commercial banks (in some cases through partial nationalization), state-owned and development banks, monetary policy and exchange rates, portfolio and FDI flows, taxation, sovereign debt and lending in local currency, international reserves, financial regulation (including restrictions on international capital mobility), and international financial institutions as tools through which to advance their goals (Ban and Bohle Reference Ban and Bohle2021; Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015; Reference Johnson and Barnes2025; Oellerich and Bohle Reference Oellerich and Bohle2024). This policy toolkit has been deployed by populists on the left and right (Da Silva Reference Da Silva2023). Left populists have used the reimposition of capital controls to insulate popular social policies from financial pressures resulting from (foreign) capital flight—for example, under Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner’s presidency in Argentina. Right populists have used capital controls to reduce the power of foreign banks in the domestic financial system; for instance, Orbán’s Hungary (Da Silva Reference Da Silva2023). Although their constituencies may be different, populist governments on the left and right are more likely than their mainstream counterparts to advocate for and implement unconventional policies that increase government control over the economy to favor their core supporters.Footnote 9 For the populist right, the privileging of “insider” domestic financial institutions and economic actors over foreign ones is at the core of financial nationalism (Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015; Reference Johnson and Barnes2025). Financial nationalist policies, if successful, can reduce the government’s foreign investor base and increase that of its captive domestic investors. Foreign investors’ threats of exit and the subsequent need to curtail it thus diminish, because the state is less reliant on them for its financing needs.

At the same time, reducing the power of foreign capital can make populist governments more beholden to domestic investors when issuing bonds. Although these investors may be more “patient” than foreign investors, their patience may have its limits. Cunha (Reference Cunha2024) demonstrates that because domestic investors are better able and more willing to monitor what their governments do, they can place greater constraints on governments than their foreign counterparts. We speculate that if populist governments increase their reliance on borrowing from domestic sources, this too could potentially increase the structural power of domestic investors. By concentrating their funding base in this way, populist governments that pursue financial nationalism become increasingly dependent on domestic investors for their financing needs. If domestic investors lose interest in purchasing domestic bonds because of risky policies (particularly those that could jeopardize debt repayment), populist governments will simply be unable to borrow. Moreover, this market disciplinary effect can happen passively rather than actively. Domestic investors’ decisions to bow out of domestic bond auctions can be devastating to the financing needs of government, regardless of whether these investors pursue exit and shift their portfolios toward foreign securities. In other words, inaction is an important lever of power for domestic investors, because it can force governments to change course in return for investors’ reengagement with primary bond markets.

We use a most-different case study design of the M5S/Lega coalition in Italy and Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz government in Hungary to examine the constraints that domestic investors place on populist governments. We anticipate that despite their economic, political, and institutional differences both governments should actively resist market discipline and rebuke foreign investors. At the same time, we expect these governments to be especially beholden to the preferences and needs of domestic investors, who we predict will be the most likely actors to pressure these governments into reversing policy course. The next section explains why we chose these cases from the wider (albeit still small) universe of populist governments, and the following sections trace market reaction to their headline economic policies.

Succumbing to Domestic Bond “Vigilantes”? Populist Governments in Italy and Hungary

Governments controlled exclusively by populists are few and far between, especially within high-income countries. Although they have arisen more frequently in emerging market economies due in part to historical legacies that sustain the attractiveness of populism among poorer and rural classes (notably within Latin America, see Grigera Reference Grigera2017; Hadiz and Chryssogelos Reference Hadiz and Chryssogelos2017) and to economic resentment in the wake of crises that have required deeply unpopular, neoliberal economic reforms in return for external financial assistance, their emergence in high-income countries has occurred only recently. Populist parties have served as coalition partners or minority parties upholding confidence-in-supply clauses throughout Europe but have rarely governed without a mainstream party to constrain their actions.Footnote 10

We test our predictions on whether populists renege on headline economic policies in the face of pressure from domestic bondholders using two cases of populist governments in high-income countries, because they should be least likely to bend to financial market pressures.Footnote 11 Populist governments in emerging markets are more constrained in sovereign debt financing than those in developed economies. Their economies (and sovereign borrowing) are more dependent on access to global credit markets and short-term credit lines (Kaplan Reference Kaplan2013; Roos Reference Roos2019), are less diversified (with a heavier reliance on commodities and natural resources, making them more vulnerable to changes in commodity prices), and are more exposed to volatility in capital flows and sudden stops.Footnote 12 Political economists have highlighted how bond investors use the high-income country classification, as well as EU membership (which both of our cases have), as peer-group heuristics for low sovereign risk (Brooks, Cunha, and Mosely Reference Brooks, Cunha and Mosley2015; Gray Reference Gray2009). Governments in high-income countries enjoy lower interest rates and higher sovereign credit ratings, on average, than those in middle-income countries. Although borrowing costs and credit ratings have been found to worsen when populists enter governments (see Barta and Johnston Reference Barta and Johnston2023, chap. 5; Johnston Reference Johnston2024), such penalties are smaller in high-income countries. In other words, populist governments in these countries can afford to take a financial “hit” to pursue their economic policies. If even these governments are forced to reverse policy course, this pressure should be even stronger for populists in the developing world.

What lends the M5S/Lega and Orbán governments to a most-different case study design is that both these cabinets radically diverged on a number of variables yet demonstrated similar reversals on substantial policies in the face of domestic bond market pressures. Differences in independent variables suggest that the M5S/Lega coalition would be more likely to bend to bond market pressure, whereas Orbán’s government would have been better insulated. Yet despite their significant differences, both governments were eventually “disciplined” by domestic investors.

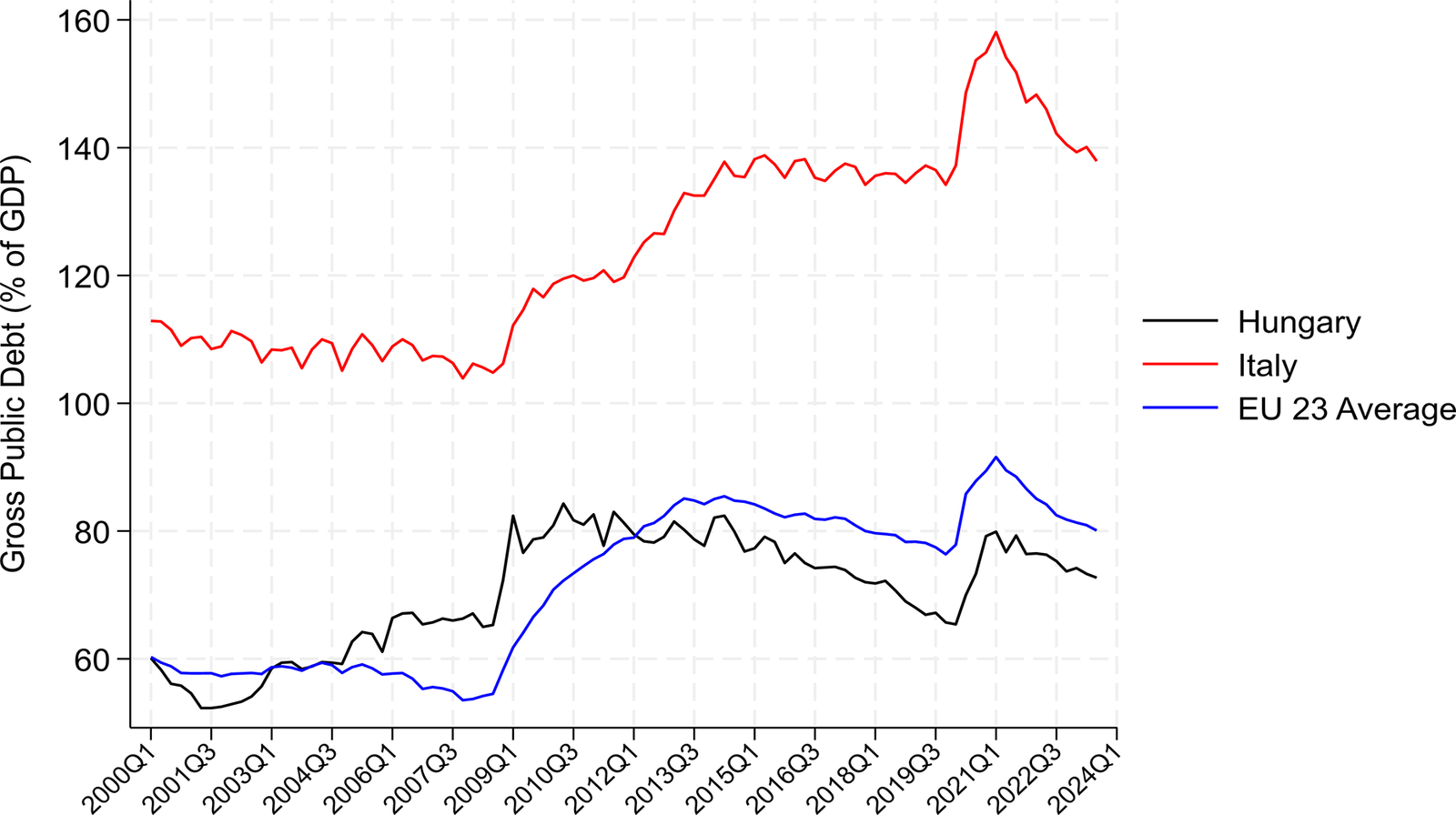

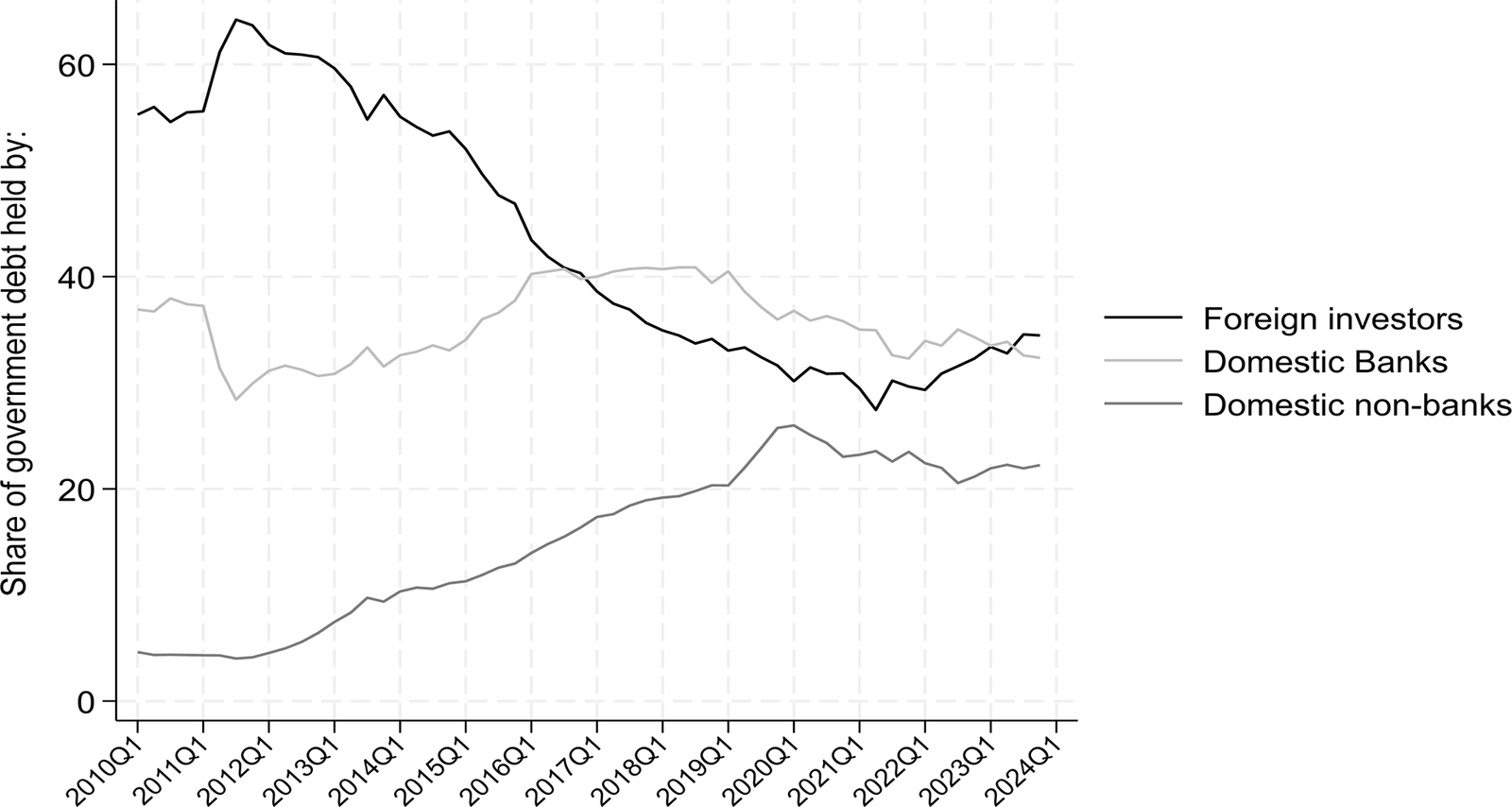

Both Italy and Hungary had radically different fiscal and financial fundamentals. Italy was one of the EU’s most highly indebted countries, both before and after the Euro crisis (figure 1). Roughly 35% of Italy’s public debt was externally held between 2000 and 2020 (IMF 2023). Public debt in Hungary, in contrast, never exceeded 85% of GDP. Although the country witnessed a jump in public debt at the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, Orbán’s II–IV cabinets successfully managed to reduce Hungary’s public indebtedness throughout the 2010s (figure 1). Externally held debt in Hungary fell from nearly 65% in 2011 to just over 30% by late 2020, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 1 Quarterly Public Debt (2000–2023)

Source: OECD (2024a) Quarterly Account. EU23 includes the original EU25 countries minus Cyprus and Malta (the OECD does not have quarterly debt data for these countries or for those that joined the EU after 2004).

Net external lending/borrowing also significantly differed between the two governments and was far more volatile in Hungary than in Italy. During the 2000s, both countries were external net borrowers but to much different degrees. Net external borrowing in Italy was 0.9% of GDP, whereas it was 7.0% of GDP in Hungary (EU AMECO 2024). Both countries became net external lenders in the 2010s, also to much different degrees (net lending in Italy was 1.0% of GDP, whereas in Hungary it was 3.4% of GDP). The size of both countries’ financial sectors was also notably different. During the 2000s and 2010s, Italy’s private credit sector as a percentage of GDP was double that of Hungary’s (80% versus 43%; World Bank 2024). Both countries also differed in their monetary autonomy, with Hungary having much greater room to maneuver when instability emerged within sovereign bond markets. As a result of its Euro-area membership, Italy lost recourse to independent monetary policy and effectively had to borrow in an international currency. In contrast, Orbán had implemented widespread financial subordination by actively undermining the National Bank of Hungary’s independence, taxing foreign banks, and reducing Hungarian debts in foreign currencies—particularly for household mortgages (see Bohle Reference Bohle2014)—while increasing issuance of forint-denominated government debt (Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015; Mabbett and Schelkle Reference Mabbett and Schelkle2015; Méró and Piroska Reference Méró and Piroska2016). These actions allowed him to resist IMF and EU pressure for financial and fiscal reform.

Both countries’ political institutions are also significantly different, affecting the ease with which their governments could withstand market pressure and steer through their preferred policies. Again, these differences suggested that Italy should be more vulnerable to bond market pressure than Hungary. The M5S/Lega coalition held a majority of seats in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate after the 2018 general election, but the government faced much higher legislative fractionalization and an effective number of parties, as well as stronger and more numerous checks and balances.Footnote 13 In contrast, Orbán’s government faced minimal checks and balances, thanks in part to Fidesz’s 2014 electoral supermajority that allowed the party to legally amend the constitution to consolidate its control of government (Armingeon et al. Reference Armingeon, Engler, Leemann and Weisstanner2023; Kelemen Reference Kelemen2017, 219).

Despite these differences, however, the market disciplined both governments, causing them to yield on their preferred policies and adopt more moderate stances. Market discipline was not a foregone conclusion, even for Italy. For months, the M5S/Lega government berated bond market investors (and the EU Commission), claiming that their People’s Budget would not be modified because of the actions of bond speculators or threats from the European Commission regarding Italy’s lack of compliance with the EU’s fiscal rules. As we outline later, when the coalition’s U-turn on its People’s Budget came in late November 2018, it was after six months of rising spreads, mass bond sell-offs by foreign investors, and the intensification of the sovereign–bank link as Italian banks were forced to purchase bonds dumped on the secondary market. Likewise, Orbán’s fiscal and financial policies were probably the most insulated from market pressure of advanced market economies, the result of more than a decade of financial nationalism (Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015; Reference Johnson and Barnes2025). But when domestic investors refused to buy enough forint-denominated debt to cover the government’s budgetary commitments and pushed up yields precipitously in the highly inflationary environment of 2021–22, the government was forced to introduce fiscal consolidation, return to forex bond markets, and capitulate to EU demands to preserve its access to EU funding.

Italy’s “People’s Budget”

Even before the March 2018 general election, it was clear to market actors that populist parties were on track to assert a notable influence on government policy in Italy. In its April 27, 2017, downgrade of Italy to BBB (placing Italian debt just two notches above junk), the credit rating agency Fitch explained that political risk had increased, as did “the possibility of populist and euro-sceptic parties influencing policy,” noting that a M5S/Lega government would “increase the pressure for fiscal loosening” (Fitch 2017).

La Lega and M5S embodied two types of populism, several features of which aligned with the populism and financial nationalism of Viktor Orbán. La Lega represented exclusionary populism, with anti-immigration sentiment and cultural discontent a major part of the party’s platform. In contrast, M5S adhered to a more inclusive populism, which channeled economic discontent and resentment toward domestic political elites (Emanuele, Santana, and Rama Reference Emanuele, Santana and Rama2022, 50). What united both parties, and concerned markets, was their Euro-skepticism and rejection of pro-market reforms that were perceived as “betraying” the average Italian to appease (foreign) financial elites during the European debt crisis.Footnote 14 Both La Lega’s and M5S’s electoral campaigns centered around hostility toward the EU and the promise to reverse crisis-induced reforms of Mario Monti’s technocratic government (Conti, Pedrazzani, and Russo Reference Conti, Pedrazzani, Russo, Bosco and Verney2022). Monti’s Fornero reform was singled out: the pension reform had been introduced unilaterally, equalized the retirement age for women and men to 66.5 years, and abolished seniority pensions, which the Lega vehemently opposed (Afonso and Bulfone Reference Afonso and Bulfone2019, 247). Lega and M5S were the only major parties that campaigned on lowering the retirement age (Maggini and Chiaramonte Reference Maggini and Chiaramonte2019, 81) and were unabashed in their criticism of the Euro and the EU’s fiscal rules, advocating for increasing deficit spending to finance their social and tax policies (Gasseau and Maccarrone Reference Gasseau and Maccarrone2023, 188). Although the 2018 Italian election yielded a hung parliament, it was clear that M5S and the Lega would either be in the new government or significantly influence it: the parties captured roughly 55% of seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 54% of seats in the Senate (Paparo Reference Paparo2018, 69).

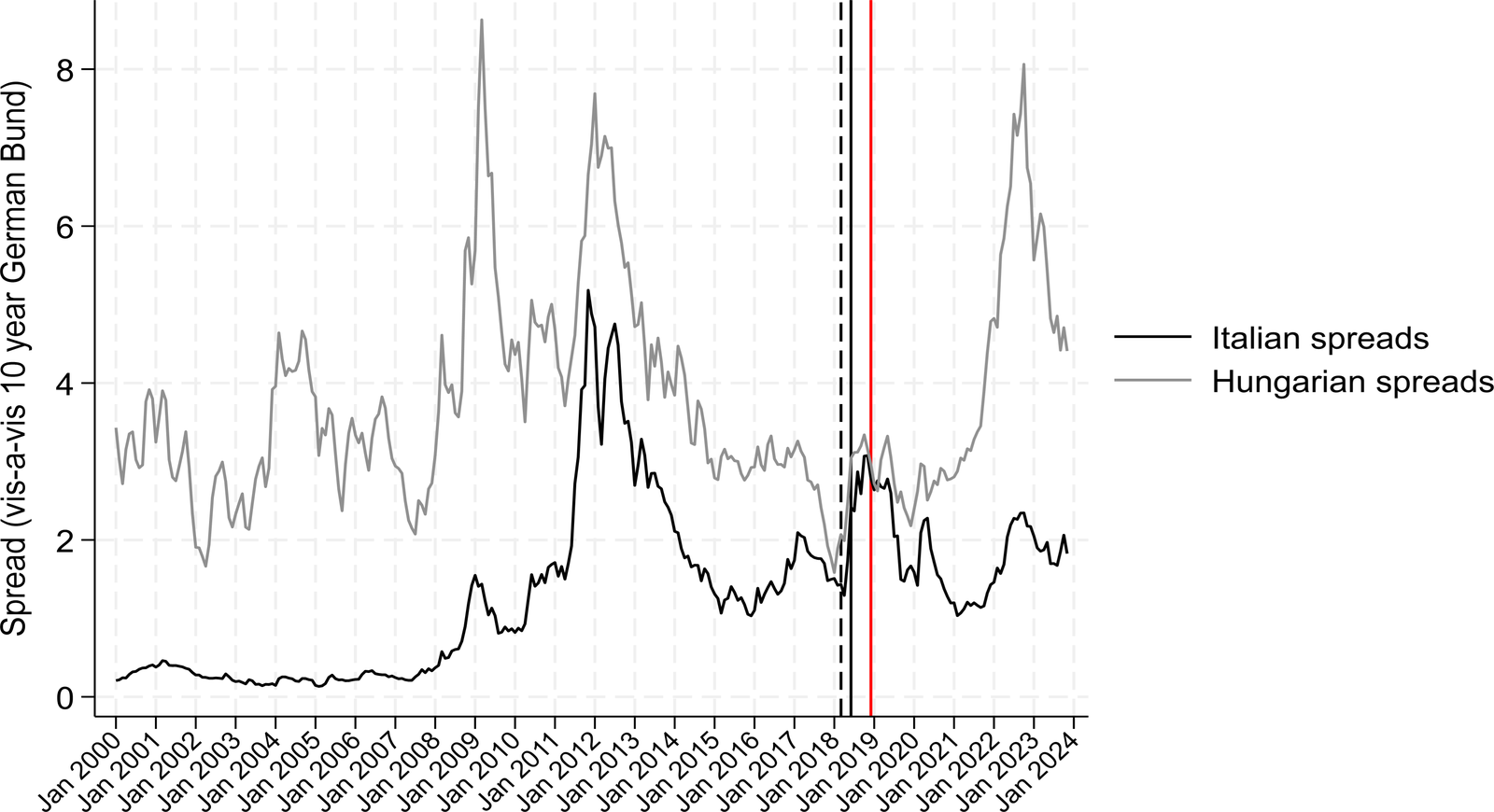

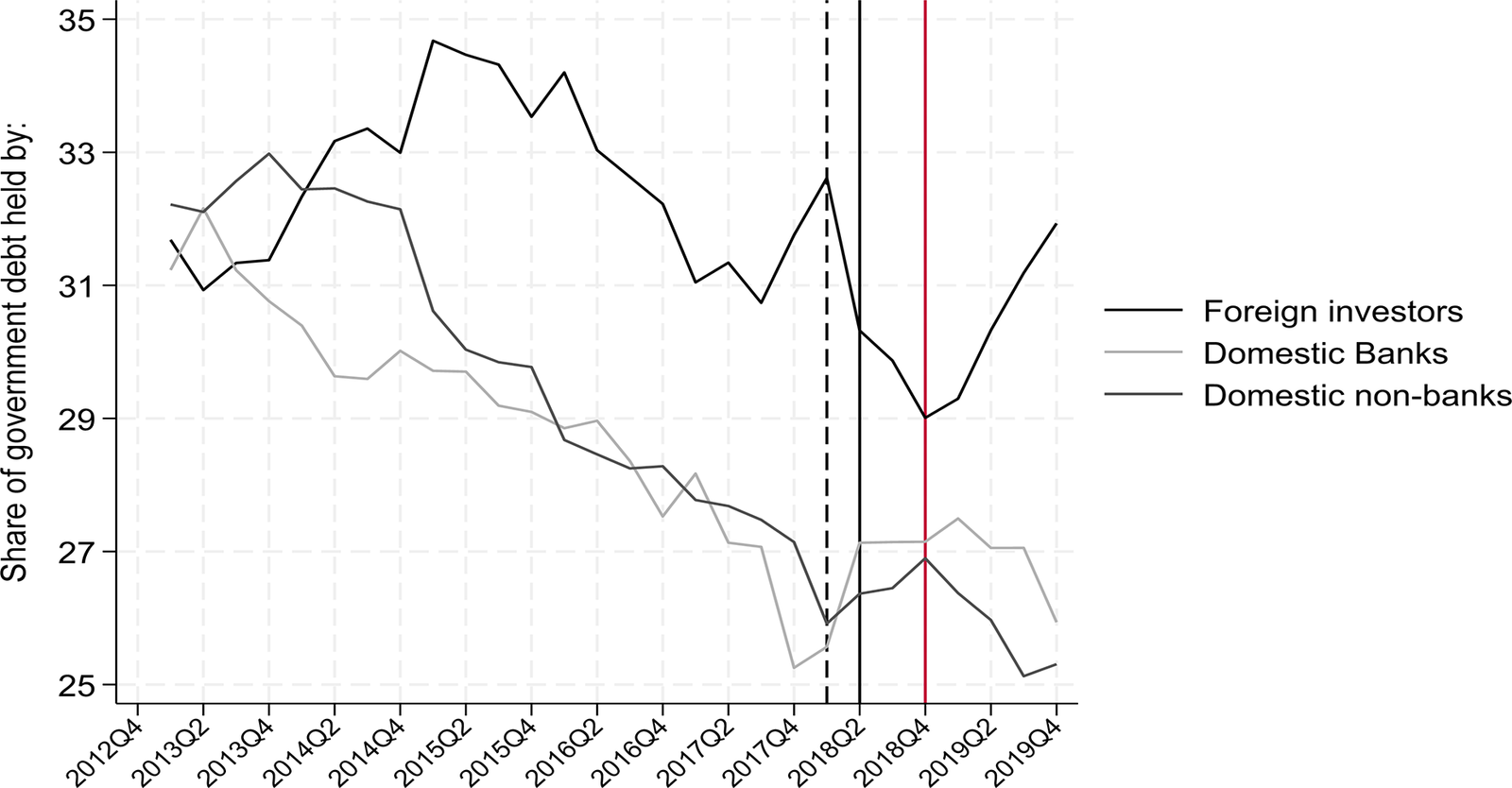

Coalition negotiations between the two parties took roughly three months to conclude before Western Europe’s “first populist government” assumed power (on June 1). Unease about Italian bonds seeped into markets after the March election: between April and June, spreads rose by more than 112 basis points (OECD 2024b; figure 2), largely driven by the portfolio decisions of foreign investors. After the election results became clear, foreigners immediately began to sell Italian securities—most of them government bonds—and domestic investors increased the shares of foreign assets in their portfolios (IMF 2019, 8). Italian banks were the domestic investors that stepped in to buy most of these bonds; by April, domestic banks had bought €45 billion in government securities (figure 3), exposing their capital ratios and funding costs to rising Italian spreads and reinforcing the sovereign–bank link.

Figure 2 Italian and Hungarian Spreads (Monthly), 2000–24

Source: OECD (2024b) monthly accounts.

Note: Dashed black line is the month (March) of the 2018 election, the solid black line marks the start of Conte’s first cabinet (June 1, 2018), and the red line is the approval of the revised budget (December 2018).

Figure 3 Holders of Italian General Government Debt (Quarterly), 2013–19

Source: IMF (2023).

Note: Dashed black line is the quarter (Q1) of the 2018 election, the solid black line marks the start of Conte’s first cabinet (Q2, 2018), and the red line is the approval of the revised budget (Q4, 2018).

Turbulence increased on May 18 when La Lega and M5S unveiled their governing “Contract.” Although both parties had toned down their anti-EU rhetoric (removing discussion of an “Italexit” from their policy agenda), the contract included the introduction of a flat tax (a key priority for La Lega), a universal basic income (a key priority for M5S), and reversal of the Fornero pension reform (a priority for both; Codogna and Merler 2019: 298–99; Conti, Pedrazzani, and Russo Reference Conti, Pedrazzani, Russo, Bosco and Verney2022). A week later Moody’s placed Italy’s Baa2 credit rating (just two notches above junk) on review for a downgrade, citing the weakening of Italy’s fiscal position in the new contract as its sole reason for doing so (Moody’s 2018a). Spreads rose, placing additional pressure on Italian banks, whose shares dove sharply: 5 of the 10 worst-performing stocks on the Italian stock exchange in May were those of Italian banks (Cornish Reference Cornish2018).

Perhaps because of uncertainty within financial markets, Conte’s government did not provoke immediate confrontation with Brussels on conclusion of the European Semester deliberations in early summer. In its June 28, 2018, meeting, the European Council (which also included Conte as Italy’s prime minister) endorsed the European Commission’s recommendation for Italy to increase its structural balance by 0.6% to comply with EU fiscal rules (Fabbrini and Zgaga Reference Fabbrini and Zgaga2019, 285). These commitments were openly abandoned several weeks later. A month before the release of the coalition’s finalized budget, M5S’s Luigi Di Maio proclaimed his commitment to electoral responsiveness over fiscal responsibility in an interview with the Corriere della Sera newspaper, saying, “If anyone wants to use the markets against the government, know that we are not blackmailable.… There is no Berlusconi in Palazzo Chigi who gave up for his companies” (Bruno Reference Bruno2024, 9). On September 27, the coalition published its Update to the Economy and Finance Document, which stated that, rather than committing to a 0.8% deficit in 2019 and a balanced budget in 2020, the government planned a deficit of 2.4% of GDP in 2019, 2.1% in 2020, and 1.8% in 2021—in blatant violation of the EU’s fiscal rules (Codogno and Merler Reference Codogno and Merler2019, 299). Government bond sell-offs by foreigners intensified: between the second and third quarter of 2018, €72 billion in Italian securities (80% of which were government bonds) left foreign investors’ portfolios, widening Italy’s Target 2 balance to its highest levels since the launch of the euro (IMF 2019, 8). By October, yields on the 10-year Italian treasury bond were more than three percentage points higher than on the 10-year German bond, a level not seen since the most intense moments of the debt crisis in 2012 (OECD 2024b; see figure 1). On October 15, fiscal loosening was further solidified as the government released the Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP), which kept intact its promises for a flat tax, universal basic income, and the reversal of the Fornero pension reform (Gasseau and Maccarrone Reference Gasseau and Maccarrone2023, 193). Just four days later, Moody’s (2018b) downgraded Italy to one notch above junk (Baa3), citing the budget and the country’s “higher susceptibility to political event risk than ever before”. Standard & Poor’s (2018) similarly cited these concerns when changing Italy’s rating (at BBB) outlook to negative on October 26.

La Lega’s Matteo Salvini and Di Maio knew the European Commission would reject the budget, and it did so on October 23—the first time it had rejected a member-state’s budget since being granted this power in 2013 (Gasseau and Maccarrone Reference Gasseau and Maccarrone2023, 193). Yet both remained defiant not only against the EU but also increasingly against financial markets, particularly against foreign investors. Di Maio claimed that the government “would no longer satisfy rating agencies and financial markets while stabbing Italians in the back” and that when faced with a choice between bond yields and the Italian people, he would “choose the Italian people” (Riegert Reference Riegert2018; see Ewing and Horowitz Reference Ewing and Horowitz2018). Similarly, just one day before the Moody’s downgrade, Salvini asked, “Should I change my policies—my agreement with Italians—on the basis of what some speculators decide in the morning? No” (Follain, Ermakova, and Totaro Reference Follain, Ermakova and Totaro2018). After the Moody’s downgrade and the European Commission’s budget rejection, Salvini became more tenacious on his commitment to the People’s Budget, claiming that “no one will take one euro from this budget” (Aljazeera 2018). Di Maio made similar claims in early November. Despite growing market panic around Italian bonds and the pressure it placed on already fragile Italian banks that increasingly had to buy them as they were sold off by foreign investors, he claimed, “The budget will not change, neither in its balance sheet nor its growth forecast” (France24 2018). In response, the European Commission (2018, 21) initiated the first step toward opening the (debt-based) excessive deficit procedure against Italy on November 21, claiming that sanctions against the government were now “warranted.”

Reversal of Fortune

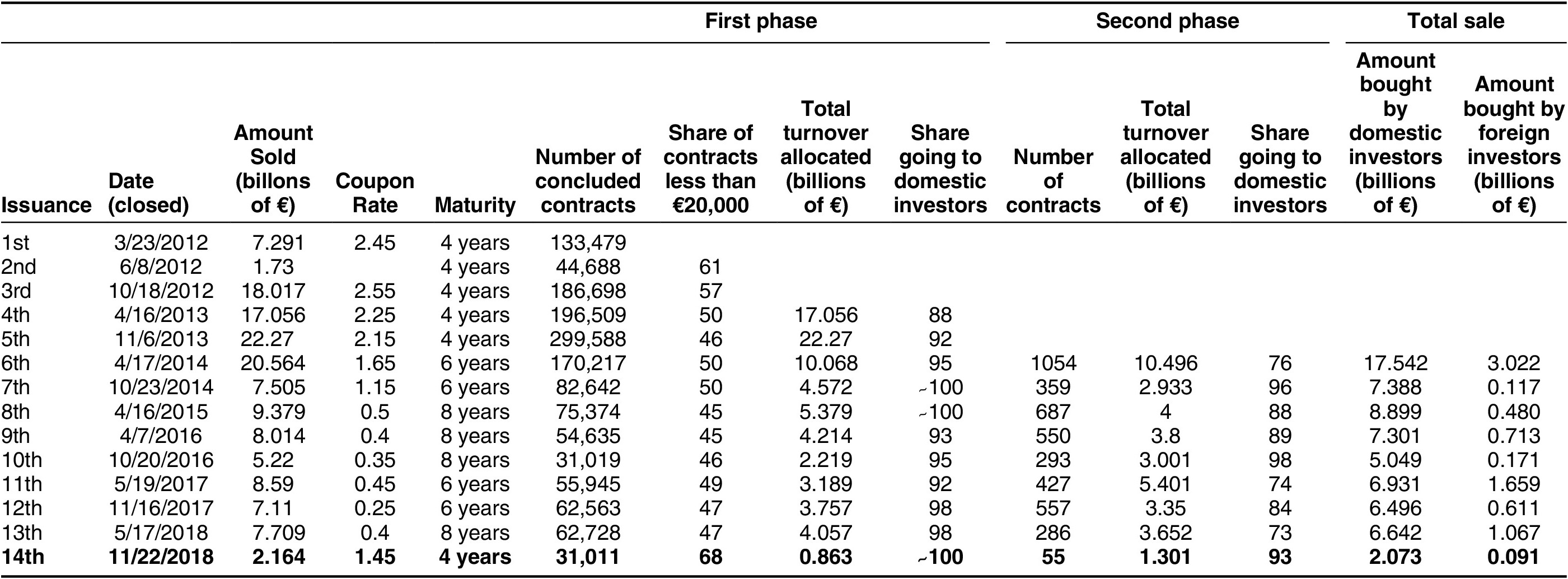

The Lega/M5S government had defined itself by opposing the EU’s fiscal rules. Yet in late November, the government changed its tone on its budget and reversed course. The coalition government had anticipated the EU actions against the budget but had not expected how domestic investors would react to these events. The November 22, 2018, bond auction of the BTP Italia sent a dramatic signal to the M5S/Lega coalition about the realities of its borrowing capabilities and domestic investors’ tolerance of their spending policies. In 2012, the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF, n.d.) introduced the BTP Italia, the first Italian government security indexed to inflation and conceived to meet the needs of retail investors. These bonds, with maturities ranging from four to eight years, are generally auctioned twice a year. In the sixth issuance (released April 17, 2014), bonds were auctioned in phases, with the first phase going to retail investors and the second to institutional investors (pension funds and asset managers). The regularity of issuance and the immediate details of their placement by the MEF allow tracking of the impact of politics on demand for Italian debt in primary markets among foreign and domestic buyers. Table 1 provides details for each issuance wave, including the total amount of bonds sold, its coupon rate and length of maturity, (for issuances after 2013) sales in its first and second phases, and the total amount of bonds in the issuance that went to foreign and domestic investors.

Table 1 BTP Italia Issuances (2012-2018)

Sources: Various MEF official communications (see Appendix A for full details)

The thirteenth issuance was auctioned on May 17, one day before the unveiling of the Lega and M5S’s governing contract. BTP’s fourteenth issuance, auctioned on November 22, was the first under the populist government at perhaps its most defiant moment in its defense of its budget. Before the fourteenth issuance, financial analysts believed that the government could sell €8 billion at the offering, close to the amount sold in the thirteenth issuance (Ainger and Hirai Reference Ainger and Hirai2018). The coalition government tried to spur interest in the auction among domestic investors, with Salvini advocating for the introduction of financial nationalist policies like tax breaks to Italians for purchasing government bonds that could limit the share of Italian debt going to “foreign investment funds” (Riley and DiDonato Reference Riley and DiDonato2018).Footnote 15 Domestic investors purchase the overwhelming majority of BTP Italia issuances (on average, more than 90%). Foreign investors rarely purchased more than a billion Euros in debt within single issuances (see table 1); thus, even if their purchases stopped, the Italian government would still be able to raise ample funds at its regular bond auctions from domestic audiences.

However, the November 22 auction proved that even Italian investors had their limit. Despite its higher coupon rate reflecting elevated political risk, the sale (€2.164 billion) was only one-quarter the amount anticipated by the government. Contract bids plummeted. Contracts from retail investors declined by 50% relative to the thirteenth issuance, with a greater share requesting smaller bond amounts: 68% of contracts in the first phase were for €20,000 or less, compared to only 47% in BTP Italia’s May 17 auction. Contracts from institutional investors declined by 80% (see table 1). Crucially, domestic purchases declined by almost 70% from the previous auction and were a mere quarter of the average of domestic purchases from the prior eight auctions. The “People’s Budget” would not be viable unless the coalition government could raise sufficient funds from domestic investors—and the November BTP Italia auction indicated they might not be able to do so.

Di Maio and Salvini could not ignore the implications of being shunned by domestic bond investors, particularly given Italy’s high indebtedness and rising debt-servicing costs resulting from the budget standoff. The day after the fourteenth BTP Italia auction, Di Maio announced that he saw “room for dialogue” on Italy’s budget plans with the European Commission. In response, Italian bond sales in the secondary debt market rallied (Ainger and Hirai Reference Ainger and Hirai2018). After a meeting with Commission officials, the Conte government scheduled a budget law on December 12 that reduced the deficit from 2.4% to 2.04%, which would avoid the excessive deficit procedure and comply with the EU’s fiscal rules; the law was approved by the Italian parliament on December 29 (Fabbrini and Zgaga Reference Fabbrini and Zgaga2019, 286; Gasseau and Maccarrone Reference Gasseau and Maccarrone2023, 195). Cuts to the budget—€7 billion in total (Fortuna Reference Fortuna2018)— largely came from M5S’s universal basic income proposal and abandoning the proposed reversal of the Fornero pension reform (Tondo and Giuffrida Reference Tondo and Giuffrida2018).Footnote 16 With the approval of the budget, Italian bond spreads fell, and holdings of Italian debt by foreign investors rose (see figures 2 and 3), indicating that markets had regained confidence in government securities. Crucially, however, this recovery in confidence among foreign investors was only made possible by the severe implications of the loss of confidence from domestic investors a month earlier.

Did La Lega and M5S voters penalize these parties for eventually choosing fiscal responsibility over electoral responsiveness? Although the next Italian parliamentary election would not happen until 2022 (when memory of investor panic in response to the People’s Budget was overshadowed by Italy’s exposure to the COVID pandemic), the 2019 EU Parliament elections in Italy shed light on voters’ confidence in both parties. The elections occurred in May, before the collapse of the coalition in August, allowing one to observe whether these populist parties incurred costs for “responsible governing” in an election that is typically considered a second-order contest where populist parties perform well (Schulte-Cloos Reference Schulte-Cloos2018). Given their compliance with the EU’s fiscal rules, neither party could legitimately claim to challenge the EU Troika. Domestic policy dominated the electoral campaigns of both parties (Newell Reference Newell2019). Of the two coalition partners, La Lega had less to lose electorally from its budgetary U-turn in the May 2019 elections. M5S’s universal basic income, not the Lega’s tax cuts, saw the biggest change in the People’s Budget, and La Lega could pivot from economic issues toward its nativist immigration policies (Jones and Matthijs Reference Jones and Matthijs2020, 73). La Lega emerged as the major victor of the 2019 EP elections, winning 34.3% of the popular vote (up from 6.2% in the 2014 EP elections), but its coalition partner did not fare so well (Chiaramonte, De Sio, and Emanuele Reference Chiaramonte, De Sio and Emanuele2020). Although M5S’s share of the popular vote (17.1%) was down only 4.1% from the 2014 EP elections, it was a far cry from the 32% vote share it secured in national elections one year earlier. This hemorrhaging of votes between the 2018 and 2019 elections was driven by demobilization (more than one-third of M5S’s voters in 2018 failed to turn out in the 2019 EP elections) and party-switching to its populist coalition partner (in some Italian regions in the north, 20–30% of M5S’s 2018 voters went for La Lega 2019; Chiaramonte, De Sio, and Emanuele Reference Chiaramonte, De Sio and Emanuele2020, 10–11). As a populist party championing the plight of the poor in Italy’s south, M5S could not rely on continued voter enthusiasm after producing a budget that placated the concerns of (domestic) capital.

Hungary: The Limits of Financial Repression

The Hungarian government has pursued financial nationalist policies ever since Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz Party came to power in 2010, creating a “financial vertical” that consolidated state control over the central bank, credit provision, and domestic financial institutions (Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015; Karas Reference Karas2022). As Orbán boasted in his February 2014 “State of the Nation” address, “We have had enough of the politics that is forever concerned with how we might satisfy the West, the bankers, big capital and the foreign press… . Over the past four years we have overcome that … subservient mentality” (Orbán Reference Orbán2014).

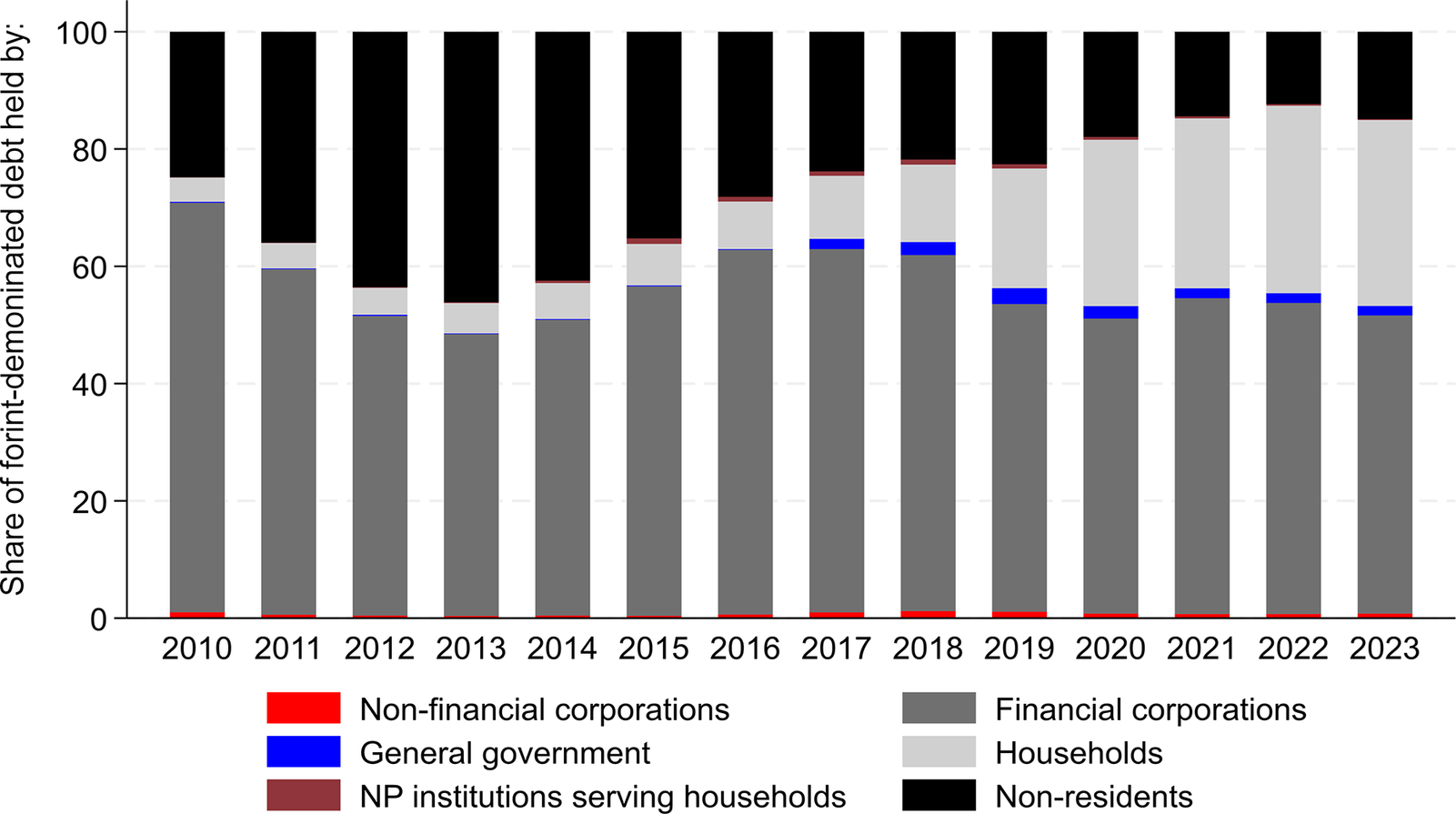

As a key part of this strategy, the Orbán government significantly increased domestic ownership in the banking sector, shifted its government debt into forint, and relied increasingly on domestic financial institutions and households to finance that government debt. When Fidesz came to power, more than 85% of the Hungarian banking sector was foreign owned; that percentage had fallen below the government’s 50% target by 2014 through a combination of foreign exit and domestic acquisition. Although foreign bond investors continued to finance Orbán’s heterodox economic policies in the 2010s despite Hungary’s bond ratings falling below investment grade from 2011–15, the Orbán government felt that empowering domestic bondholders would give it greater policy control and free it from the threat of foreign “bond vigilantes.” Forex-denominated government debt fell precipitously from more than 50% of the total when Orbán took power to around 15% by 2020 (Kiss Reference Kiss2024). Although foreign investors held nearly 65% of Hungary’s total government debt in 2011, this had fallen to just over 30% by late 2020 (National Bank of Hungary 2024; see figure 4). Moreover, although nonresident investors held 44% of Hungary’s forint-denominated government debt in 2012, this percentage steadily declined to only 14% by 2021 (figure 5).

Figure 4 Holders of Hungarian Total General Government Debt (Quarterly), 2010–23

Source: Authors’ calculation using data from the National Bank of Hungary (2024).

Figure 5 Holders of Forint-Denominated Hungarian Government Securities (over 1- Year Maturity), 2010–23

Source: Authors’ calculation using National Bank of Hungary data (2024). NP indicates nonprofit.

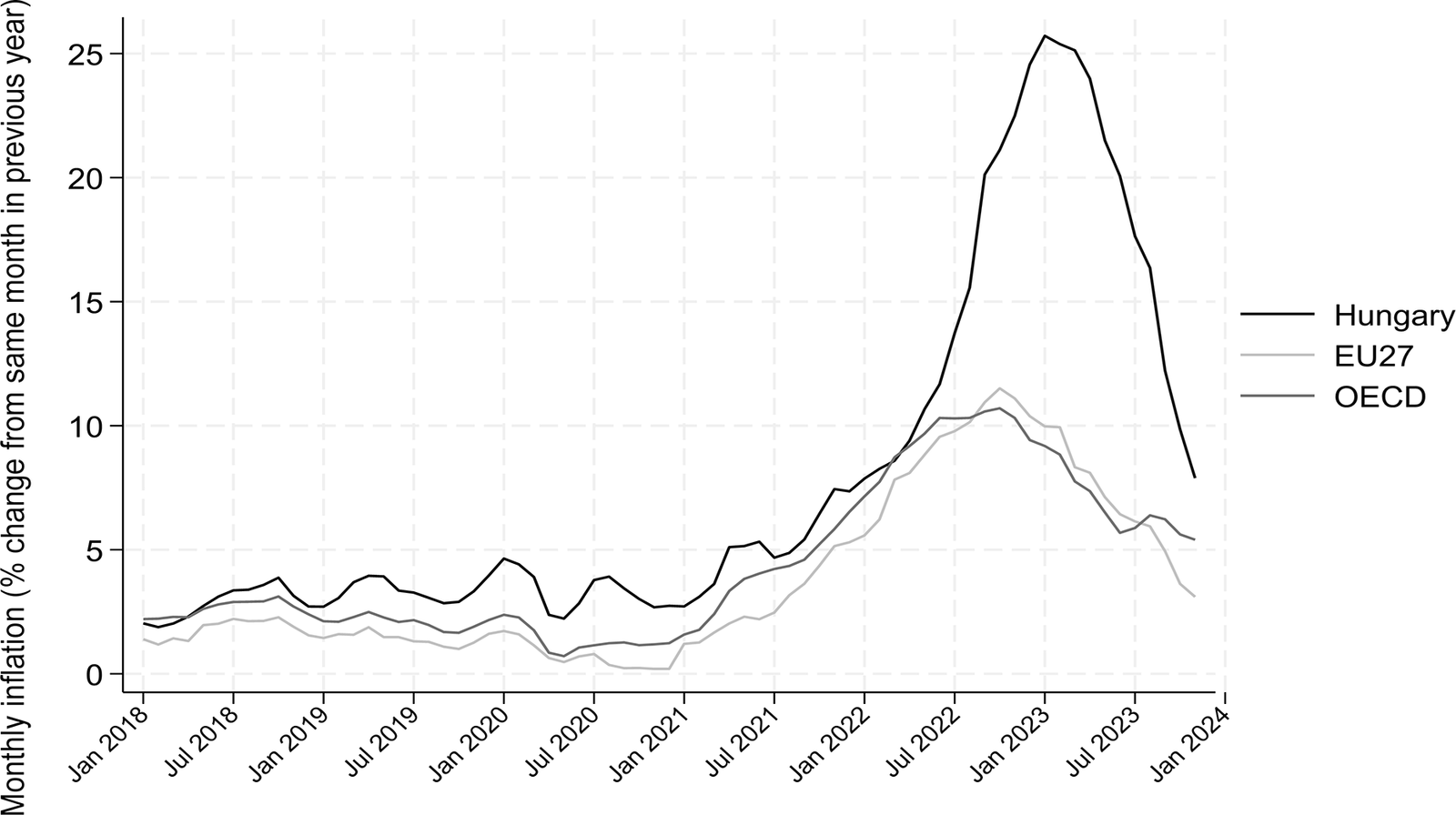

Over the course of two decades, the Orbán government transformed Hungary’s government debt structure from one heavily reliant on foreign investors and currencies to a forint-centric domestic base, substantially increasing the structural power of domestic finance in Hungary. But even though domestic bondholders may typically be more patient than foreign ones, they too have their limits. As inflation (figure 6) and government financing needs rose in Hungary in 2021–22, domestic investors facing unpredictable returns lost their appetite for forint-denominated bond holdings even as yields rose significantly (see figure 2). As a result, the Orbán government was forced to pull back on key election spending promises, return to foreign bond markets, offer more attractive inflation-linked forint bonds to lure domestic investors, and attempt to secure endangered EU funds by agreeing to implement rule-of-law reforms and support EU financing for Ukraine. Notably, Hungary’s international bond ratings remained investment grade throughout this crisis, and foreign investors exhibited relatively strong support for Hungarian forex bonds. Once inflation began to subside in 2023, the government punished recalcitrant domestic investors through financial repression policies intended to force banks and households to invest in government bonds.

The Looming Crisis

Hungary’s failure to control inflation and the government deficit after the 2020 COVID shock and in the leadup to April 2022 parliamentary elections made the Orbán government’s heterodox economic model vulnerable for the first time since its consolidation more than a decade earlier. Although COVID-driven inflation hit countries around the world, Orbán’s preelection spending added significant fuel to the fire. This spending included tax breaks representing 3–4% of GDP, wage hikes, an extra month of pension payments, and bonuses for armed forces personnel, among other extravagances (Csonka Reference Csonka2022). At the same time, the EU finally began to criticize Hungary’s rule-of-law deficiencies by delaying disbursement of funding tranches, rather than with mere words. Despite Orbán’s bitter criticism of the EU, Hungary has long been a leading per-capita recipient of EU funding, which represented an important government revenue source. Orbán insisted that Hungary’s strong economy would enable it to rebound quickly from these setbacks.

The Hungarian government turned to bond markets to help meet its precipitously rising funding needs, raising its planned domestic bond issuance by nearly a trillion forint (roughly $2.8 billion) in 2021 (ÁKK 2021). But domestic investors were not on board, with commercial banks reducing their government bond holdings in 2021 and households reluctant to increase their purchases to anywhere near the government’s desired rate. As the ÁKK government debt agency noted in its 2021 annual report, rather than rolling over their debt, “the redemption of retail securities and domestic bonds exceeded the original plan by 28–39 percent due to higher buybacks during the pandemic in the Hungarian State Treasury and retail banks,” with total debt redemption 11% over the ÁKK’s target (19). The National Bank of Hungary’s (MNB) quantitative easing program initially propped up the domestic bond market, and its balance sheet exploded, with its debt holdings rising from 42.2 billion forint in 2020Q1 to 3,618.6 billion in 2022Q1 (23). But with its bond purchase program ending in late 2021, the government could no longer rely on this support.

The ÁKK noted that “the year 2021 was again an extraordinary year.… During the year government securities’ yields increased substantially in all maturities. Long-term yields went up due to increasing inflation rates and expectations in developed economies and phasing out the government bond purchase program of the National Bank of Hungary, while short-term yields increased following the policy rate hikes of MNB from June 2021” (ÁKK 2021). Before the crisis the ÁKK had a target band for forex debt of only 10–20% of the total and had not issued new forex debt since 2018. It had also targeted domestic retail holdings of forint-denominated securities to reach 11 trillion forint by 2023, buoyed by an incentive program introduced in June 2019 that made income from government securities tax-free for households. In the face of the COVID crisis, neither of these targets would hold. The government was forced to turn to foreign markets because domestic investors were reluctant to finance the government in the quantities necessary to meet its spending plans. After a single euro issue in 2020, the ÁKK had not planned to issue forex bonds in 2021 but in the end issued four of them for a total of 2.7 billion euro (in USD, euro, and renminbi), in great part to “pre-finance” 2022 government spending. For the first time since 2011, the share of government debt held by foreign investors rose, rather than fell (see figure 4).

This pressure from domestic bond markets led the Orbán government to announce in December 2021 that it would reduce its 2022 deficit target to 4.9% of GDP from 5.9%, postpone its purchase of Budapest’s international airport, and freeze $1 billion in other planned investments. Analysts observed that “with tax cuts and big state expenditure due in the first quarter ahead of an election in April, the government is likely trying to mute pressure on the local government bond market where yields have increased in past weeks … [Because of unfavorable market pressure] the ÁKK has reduced planned forint-denominated bond sales at auctions [in 2022] substantially” (Than Reference Than2021). Earlier in the fall, the government had also announced that it would introduce price caps on fuel and six basic food items to shore up public support and administratively reduce inflation, which was more than 7.5% per annum by the end of 2021 (see figure 6).

The Russian Invasion and Runaway Inflation

Russia’s February 24, 2022, invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent market panic and energy price spikes came at the worst possible time for the Orbán government, right before the April parliamentary elections and as it was attempting to get its fiscal situation under control. The forint fell to record lows against the euro, and the MNB hiked interest rates by 1% in March. This began a cycle of forint depreciation, MNB interest-rate hikes, and accelerating inflation that saw the Hungarian inflation rate diverge significantly from that of the EU as a whole, rising sharply after the invasion and reaching a peak of more than 25% annually by January 2023 (see figure 6).

Hungary’s domestic bond market did not react well to these developments. At its March 7, 2022, auctions, the ÁKK had to lift the mandatory market-making requirements for Hungarian primary dealers, with ÁKK head Zoltan Kurali saying, “It would be useless to let primary dealers punish one another by pushing yields higher and higher by trying to fulfill their obligations” (Szakacs and Than Reference Szakacs and Than2022). The domestic bond market was rocked again in early April after the European Commission announced a new disciplinary procedure against Hungary for its rule-of-law failures, with the ÁKK forced to reduce its already low offerings of its benchmark 10-year forint bond by one-third (EmergingMarketWatch 2022a). Although sales somewhat recovered in volume, yields exploded (see figure 2). In May, rising inflation prompted households to sell off government securities, and the MNB temporarily resumed its purchases to prop up the market (EmergingMarketWatch 2022b). The ÁKK introduced a new inflation-linked bond in June to attempt to lure investors back to the market. Nevertheless, despite increasing government spending needs, by July 2022 retail investors held 64 billion forint less in government bonds than at the end of 2021 (bne Intellinews 2022).

The Hungarian government was forced to react to this market pressure. At a press conference after Orbán’s Fidesz Party retained its supermajority government in the April 2022 elections, Orbán insisted that he stood behind his spending promises and that Hungary would not need to engage in fiscal consolidation (Csonka Reference Csonka2022). This bravado faded quickly. On May 24 Orbán pleaded economic woes as justification for extending the pandemic-era state of emergency in Hungary, allowing him to rule by decree (Emerging Markets Monitor 2022). A few days later the government introduced spending cuts and new “windfall taxes” of more than $2 billion on banks and other major companies (Komuves Reference Komuves2022). Hungarian bankers complained bitterly about this revenue grab, and the markets were not sufficiently impressed to firm up substantially. As Economic Development Minister Márton Nagy lamented, “These announced steps strengthen further our shock absorbing capacity. This is not properly reflected by the financial market reactions, like government bond and foreign exchange market movements in the last days” (Reuters 2022a).

With domestic bond markets reacting poorly to Orbán’s windfall taxes and EU funding increasingly in question, in July the Orbán government introduced more serious fiscal measures that required reneging on core electoral spending promises. These tax hikes (including on small businesses) and cuts in energy subsidies, ministry spending, and investment amounted to a reduction of 10% in the original 2022 budget. Demonstrations rocked Budapest in late July in response to the announcements. The Financial Times cited a mechanic complaining that “I thought [Orbán] had our best interests at heart. For him to turn around and just slap us with higher taxes and energy bills and pretend it’s business as usual, that told me he is not the defender of the people” (Dunai and Wheatley Reference Dunai and Wheatley2022).

In its search for funding, the Orbán government once again had to turn to foreign bond markets, despite its ideological aversion to doing so. The European Commission’s 2023 Country Report–Hungary noted, “Due to decreasing domestic demand for government securities in 2022, debt management had to rely increasingly on foreign borrowing” (5). In June the ÁKK raised its original 2022 forex borrowing target and issued $3.8 billion worth of USD and euro bonds (Reuters 2022b). At the same time, it affirmed that it would keep the total forex debt ratio below 25% and that this would be the last forex bond offering for 2022 (Budapest Business Journal 2022). International investors reacted enthusiastically, with the bonds oversubscribed and yields reasonable (MTI Daily Bulletin 2022). Meanwhile, as the domestic bond market continued to stall, in late September 2022 the Orbán government introduced two domestic bonds that it hoped would more effectively attract subscribers: the Bonus Hungarian Government Security (BMÁP) with an initial annual interest rate of 11.32% and a revised inflation-linked bond (PMÁP) with an initial interest rate of 11.75% (EmergingMarketWatch 2022c; Erste Group 2022a). The ÁKK also went back on its claim that its June 2022 forex offering would be the last of the year, floating both a green euro bond and a privately placed bond (its first ever) in November (Euromoney Institutional Investor 2022).

Although the Orbán government had previously asserted that it could press on and raise money on the market to replace lost EU funds if necessary, the government’s rhetoric changed markedly over the course of the year as both domestic and foreign investors began to focus on the increasingly precarious state of Hungary’s EU funding. When forex and domestic bond yields spiked in the latter half of the year in response to increasing indications that the EU would suspend Hungary’s Cohesion funds and that Hungary might lose access to EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) funds, the Orbán government had to make formerly unthinkable compromises with the EU. The government verbally committed in September to meeting all 17 of the rule-of-law targets required to access EU Cohesion funds (Reuters 2022c). The RRF funds remained of special concern, because failing an EU agreement on its Resilience and Reform Plan by the end of the year, Hungary would irrevocably lose access to 70% of the funds (Erste Group 2022b).

Under extreme market pressure, the Orbán government agreed on December 12 to a package deal under which Hungary accepted EU financing for Ukraine and a global minimum corporate tax in exchange for approval in principle of Hungary’s Resilience and Reform Plan, paving the way for Hungary to receive RRF funds of more than 5.8 billion over five years (Szakacs and Komuves Reference Szakacs and Komuves2022). Although this deal avoided a potentially catastrophic bond sell-off, much of Hungary’s Cohesion funding and the RRF funds themselves would remain frozen until Hungary met stringent EU-defined targets, most importantly those involving rule-of-law issues (European Commission 2023). The Orbán government could thus not immediately count on EU funding to fill its budgetary holes. An ÁKK announcement the following week reconfirmed that the government would maintain its fiscal discipline in 2023 to reduce inflation and satisfy bond markets, while also admitting that it would miss its 11 billion target for retail securities volumes and would raise the forex debt target cap to 30% (EmergingMarketWatch 2022d).

Reluctant Investors and Financial Repression

Despite the EU deal and the government’s reluctant fiscal conservatism, domestic bond investors still shied away from government markets in early 2023 as inflation was peaking. Although the ÁKK successfully floated $4.25 billion of USD bonds on January 5 (Reuters 2023), it had to reduce the issuance of its benchmark domestic bonds in its January and February auctions because of low demand (EmergingMarketWatch 2023a; 2023b). Fed up with the recalcitrance of domestic investors, the Orbán government turned to its financial nationalist playbook to engage in more comprehensive financial repression, this time involving more sticks than carrots. On May 31 the government announced a series of measures to both cajole and force domestic banks and households to invest in Hungarian state debt instruments. Money sitting idle in savings accounts would now be subject to a 13% “social contribution tax,” households could buy bonds without fees, and banks would be required to inform customers regularly about the potential returns on government bonds as opposed to deposits. Investment funds would be required to hold a significant proportion of their assets in government securities. Banks that increased their government bondholdings could earn a partial break on the windfall tax levies that had been introduced the previous year (bne IntelliNews 2023a).

With these measures, the government expected to raise 1.8 million forint in new investment and lower bond yields, which in turn would reduce the government’s interest-rate burden. Economic Development Minister Márton Nagy claimed in relation to the new rules on bank deposits, “We are steering the population toward forms of saving where money retains its real value. There is also the issue of self-financing as a strategic objective” (Szumski Reference Szumski2023). As for the banks, Nagy noted that to be eligible for their windfall tax obligations to be halved, some would need to increase their government securities holdings by 40–50%. Not surprisingly, the Hungarian bankers’ association bitterly protested (EmergingMarketWatch 2023c).

The measures were successful inasmuch as they quickly led to yield declines (see figure 2) and an increase in household ownership of government bonds (bne IntelliNews 2023b). In October the Economic Development Ministry declared that its financial repression strategy had been “extraordinarily effective,” generating demand for 1.2 billion forint of government securities from households (Daily News Hungary 2023), although market analysts noted that this was well under the 1.8 billion originally anticipated (EmergingMarketWatch 2023d). But the ÁKK once again had to turn to foreign investors to fill the domestic funding gap, issuing its largest-ever euro bond in September 2023 and raising its 2023 foreign financing plan (GlobalCapital 2023). In continuing efforts to mobilize household savings, Finance Minister Mihaly Varga announced in November 2023 that the government would preemptively create a securities account for each Hungarian citizen (bne IntelliNews 2023c). Having been disciplined by its domestic bondholders in 2021–22, the Orbán government responded by disciplining its bondholders in return.

Despite their entrenched control over Hungarian politics, Orbán and his Fidesz Party paid a political price for their backtracking. In early July 2022 polls had indicated more than 60% support for Fidesz, an even higher percentage than the party had received in the April elections. But after the government raised taxes and reneged on its populist spending promises later that month, protestors took to the streets, and the party’s poll ratings immediately began a steady slide downward (Politico 2025). Amidst economic malaise and corruption scandals, former Fidesz official Péter Magyar led the center-right Tisza (Respect and Freedom) Party to a strong showing in the 2024 European Parliament race, holding Fidesz to under 50% in an election for the first time since it had come to power in 2010. Fidesz continued its slide. By late 2024 Tisza had not only pulled ahead of Fidesz in the polls (Gergely Reference Gergely2024; Politico 2025), but more people also reported trusting Magyar with the Hungarian economy than Orbán (Körömi Reference Körömi2024).

Conclusion

The rise of populism has led to a shift toward illiberal democracy, even in high-income countries (Mudde Reference Mudde2021). Populists-turned-autocrats have radically altered political institutions, eliminating checks on their power (such as in Orbán’s Hungary or Erdoğan’s Turkey). Although these efforts have enabled populists to deliver on their policies, we argue and demonstrate that financial markets remain an important constraint on populist governments. In line with the market discipline hypothesis, we find that markets do constrain populists’ macroeconomic policies, but that these constraints do not work through foreign capital flight or through the EU’s fiscal rules—indeed, populist governments in both Italy and Hungary have in the past openly flouted the EU when it threatened disciplinary action against their budgets. Instead, populists are most directly constrained by inaction from domestic investors, an audience their policies are designed to privilege and, in extreme cases, hold captive.

Our findings have implications for a large literature in IPE on the government–market nexus within an increasingly globalized and financially integrated world. IPE scholars focusing on the influence of foreign investors emphasize that bondholders’ power comes from exit, voice, and loyalty (Cohen Reference Cohen, Gilbert and Helleiner1999). Our findings suggest that strategic inaction can be a surprisingly powerful use of voice. Domestic investors (largely banks and households) in Italy and Hungary exerted their power over populists’ economic policies through the deliberate refusal to purchase more government bonds. Foreign investors used the option of exit (willingly in Italy, coercively in Hungary), but populists did not bend to this capital flight. Rather, it was a loss of appetite for bonds among domestic audiences that forced these governments’ hands. Our findings complement recent work from Raphael Cunha (Reference Cunha2024), who draws attention to the “underappreciated role” (and underappreciated power) of domestic investors in an era of globalized capital and asset managers.

Our findings also have implications for an emerging literature in CPE on the economic policies of populist parties and the rise of economic and financial nationalism (Johnson and Barnes Reference Johnson and Barnes2015; Reference Johnson and Barnes2025; Oellerich and Bohle Reference Oellerich and Bohle2024; Rathgeb Reference Rathgeb2024). These works have meticulously dissected the content of populists’ economic policies, how they are shaped by domestic institutions, and how international actors can unwittingly enable them, but they have not explored how markets might discipline them in practice. Empirically there is good reason for this lack of attention because few populist parties have managed to obtain full control over government and fully implement their policy agenda. In examining two of the few cases of Europe’s truly populist governments, we can observe the pathways that market discipline takes in bending economic nationalists into submission. Ironically, populists in these countries were not forced to change course because of the behavior of the outsiders that they so disparage but because of the loss of confidence among insiders whose interests they champion.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592725000817.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dorothee Bohle, Ben Braun, Charlotte Rommerskirchen, Dóra Piroska, participants at the 2024 Council for European Studies conference in Lyon, France, four anonymous reviewers, and the editors for their helpful feedback. We also thank Stepan Verkhovets for his invaluable research assistance. Any errors are attributed solely to the authors.