5.1 Introduction

Special and differential treatment (S&DT) has a long history in multilateral trade negotiations, dating back to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) of 1947. Born as a response to the development gap among members, S&DT has evolved into a framework of rules – both substantive and procedural – intended to grant developing countries more extensive permissions and longer implementation periods than originally outlined in the GATT rules. Scholars agree that Latin American countries have played a pivotal role in shaping these rules, redefining the policy space for developing nations in the realm of trade governance (Tussie and Glover Reference Tussie and Glover1993; Peixoto Reference Peixoto2010). By “policy space” we mean “the combination of both the de jure policy sovereignty and de facto national policy autonomy” that each country possesses (Mayer Reference Mayer2009, p. 376).

How these rules manifest in preferential trade agreements (PTAs) has remained overlooked in international relations and international law studies, which have tended to focus on S&DT in multilateral agreements. This chapter aims to fill this gap by exploring how Latin American PTAs – signed among countries in the region and signed with extra-regional trade partners – have included S&DT principles and operative clauses.Footnote 1 In doing so, one of the main contributions of our study is to explore the S&DT dimension in the PTAs, tracing its reach across the different commitments and chapters. In addition, we describe the evolution of the development-related policy space notion in trade agreements recently signed by Latin American countries and the differences concerning the legal S&DT architecture across PTAs.

Our main argument is that S&DT clauses in Latin American PTAs are a diverse set of provisions dependent on the composition of negotiating parties, the purpose of the agreement, and the historical context. We find that S&DT clauses are rarely placed in ad-hoc chapters but are more frequently presented in various parts of the agreements relying on general criteria or across-the-board S&DT instruments. Our sample of PTAs shows that S&DT provisions often appear as a patchwork of exclusions, including exemptions, transition periods, and safeguards. S&DT may be found in connection with specific trade topics, considered “sensitive” to local development strategies, and thus often constitute red lines for negotiation purposes.

Among those often included are tariff exclusions, albeit with limited scope, as well as special provisions in chapters dealing with rules of origin, reliance on longer transition periods for implementing sanitary and phytosanitary regulations, the use of exemptions in services’ commitments, and, more recently, the inclusion of specific chapters devoted to capacity building. In some agreements, S&DT is reflected by the absence of a specific trade topic upon a developing country’s request. In other cases, S&DT includes clauses of best endeavor, reducing the level of ambition required in the commitments to provide for greater flexibility. Finally, in some cases, Latin American countries must accept a “less favorable” treatment under an Agreement than their developed countries’ counterparts.

The chapter is organized as follows: First, we look back at the evolution of the development dimension in the international trade system. This is followed by a discussion of our analytical framework. Third, we characterize and classify S&DT in Latin American PTAs using our framework. Lastly, we discuss findings and propose a new typology for understanding S&DT approaches in Latin American PTAs.

5.2 The Development Dimension in International Trade Agreements – Early StagesFootnote 2

Development asymmetries have been part and parcel of the international trade discussions in the negotiations leading up to GATT in 1947. In fact, of the original twenty-three Contracting Parties, ten were developing countries, including Brazil, Chile, and Cuba from Latin America.

Until then, S&DT was not considered in trade agreements (Bacchus and Manak Reference Bacchus and Manak2021). The GATT/1947 initially had only a few mechanisms to deal with and eventually to reduce the impact of asymmetries among countries. However, GATT provisions allowed many mechanisms for countries to manage their integration into world markets through some form of flexibility. For instance, signatory parties could apply antidumping measures, safeguards, and compensatory duties without having to follow strict and detailed procedures. Countries facing severe distress in their balance of payment could apply import restrictions.

Interestingly, no attempt was made to categorize any types of countries with differing obligations in the GATT/47. This absence of formal distinctive treatment for developed and developing countries in the original treaty could be explained by the dominating idea that concessions should, in principle, be reciprocal among trade partners. However, Contracting Parties faced different development needs. The United States was emerging as the leading economic power after the end of the Second World War; European Countries and Japan were undergoing recovery from the economic, social, and political effects of the war; and other countries, including some in Latin America, were following an economic policy characterized by industrialization objectives and reliance on import substitution instruments.

Based on prior experience from early GATT rounds, developing countries quickly identified that many rules of the multilateral system did not satisfactorily address the developmental asymmetries among countries. They began to question, for example, the appropriateness of applying the most-favored-nation (MFN) principle indiscriminately/or without clear differentiation between developed and developing countries (Irwin et al. Reference Irwin, Mavroidis and Sykes2008).

However, it was not developing countries’ criticism but concerns from the US and other like-minded countries that led to some changes. The US pointed to the existence of trade distortions caused by European protectionist policies in agriculture and, therefore, elevated this topic to the center of negotiations. As a result, GATT’s Contracting Parties called for the establishment of a special group to study the topic (Ingco and Nash 2014). The final report of this special group, known as the Haberler Report (1958), concluded that the regulatory framework for trade liberalization generated different effects for developed and developing countries. As a result of the discussions that followed, in 1961, the Declaration on the Promotion of Trade in Least Developed Countries was agreed upon (De Vylder Reference Vylder2007). Several of the conclusions contained in the Haberler Report were included in this legal document.

Following the Haberler Report, in 1963, trade ministers agreed to initiate negotiations to amend GATT to address trade and development concerns more explicitly. What stands out is the inclusion of Part IV in the GATT. Although recognizing the effects of asymmetries in trade, this reform imposed few, if any, concrete obligations (Jackson Reference Jackson2006). In the following years, the tensions between upholding reciprocity and addressing development needs, both in terms of gradualness and diversity, increased. Poorer countries advocated trade rules that favored the promotion of development-friendly policies, which would be potentially hampered by the direct application of the MFN principle (Hoekman Reference Hoekman2005). This was coupled with the perception that the reduction of tariff barriers was insufficient to ensure freer trade, since governments had developed other behind-the-border mechanisms that limited the potential gains from import liberalization.

As a result, the Tokyo Round (1973–1979), in addition to promoting tariff reductions, was the first trade round to address non-tariff barriers. The Tokyo Round negotiations also included the adoption of the “Understanding on Differential and More Favorable Treatment, Reciprocity and Broader Participation of Developing Countries”, known as the Enabling Clause. This clause allowed parties in the GATT to negotiate a more favorable treatment for developing countries without applying such treatment to other contracting parties. It encouraged preferential tariff schemes in favor of developing countries as well as possibilities to negotiate more flexible regional arrangements among less developed contracting parties. Lamp (Reference Lamp2015) suggests that these S&DT provisions were more the result of developed countries’ preferences rather than those of developing countries. The Tokyo Round was thus marked by tension among the so-called transatlantic powers (USA and European Community-EC) and developing countries, members of the so-called Informal Group of Developing Countries (Peixoto Reference Peixoto2010).

The Uruguay Round began in a context where many developing countries were somewhat empowered by S&DT flexibilities. However, the Marrakech package was markedly uneven in favor of developed countries and dealt a hard blow to the S&DT (Steinberg Reference Steinberg2007). There was no consensus among developing countries for the adoption of a general “umbrella” framework for S&DT provisions, although there were not many chances of fighting for that either. Developing countries were at a crossroads – would they accept all the rules and obligations resulting from the negotiation, or would they remain outside the organization? In fact, the single undertaking resulted in causing developing countries and developed countries to assume very similar undertakings based on rules commonly biased in favor of developed countries. The concept of S&DT was changed, and its scope was restricted; it was a reflection of the unwillingness of developed countries to continue granting special treatment, particularly to middle-income countries (Whalley Reference Whalley1999; Fukusaku Reference Fukusaku2000; Tempone Reference Tempone2007).

5.3 Special and Differential Treatment in a Nutshell

As noted earlier, trade agreements tend to reflect developed countries’ needs, priorities, and preferences. This holds true in both multilateral and PTA negotiations. Larger countries are more likely to be “rule-makers” and set the patterns that shape PTAs. In turn, this has been proven to have a distinctly positive effect on their exports – to the detriment of poorer countries – (Seiermann Reference Seiermann2018). As a result, everything that differs from the “template” of PTA texts built by the larger economies is likely to be considered as an S&DT demand. These demands, which result from developing countries’ industry needs, advocate for a set of protection and assistance tools in the form of special clauses (Hoekman Reference Hoekman2005; Chang Reference Chang2006).

According to Weinhardt and Schöfer (Reference Weinhardt and Schöfer2021, p. 5), S&DT can be defined as

“an ordering principle that (a) differentiates between groups of states that are understood to be in a more advantageous position than the members of the other group; and (b) stipulates that those perceived to be in a less advantageous position are given more extensive rights, and/or those perceived to be in a more advantageous position were given more extensive obligations.”

Other scholars refer to S&DT provisions in the context of providing sufficient policy space, which is often reconfigured after signing a trade agreement, owing to disparities in development among parties (Mayer Reference Mayer2009; Di Caprio Reference DiCaprio2010).

There are at least two broad discussions on S&DT provisions. The first debate is about exactly which Members can use these provisions. Weinhardt and Schöfer (Reference Weinhardt and Schöfer2021) identify three approaches by which S&DT is assigned in trade agreements: a definition of certain criteria that countries need to accomplish to access these provisions, a list with specific countries, and auto-election.Footnote 3 The second debate concerns the scope and types of S&DT provisions. Different proposals exist on how to define and categorize such provisions.

The WTO Secretariat suggests a typology of six different types of S&DT provisions. These include:

“1. Provisions aied at increasing developing countries’ trade opportunities; 2. Provisions under which WTO Members should safeguard the interests of developing country Members; 3. Flexibility of commitments, of action, and use of policy instruments; 4. Transitional time periods; 5. Technical assistance; 6. Provisions relating to LDC Members” (World Trade Organization Reference Baldwin2021).

Scholars such as Matsushita et al. (Reference Matsushita, Shoernaum, Mavroidis and Hann2015), for their part, posit that most WTO agreements contain some forms of exceptions, longer phase-in periods, or special provisions for developing countries. They argue that these provisions were designed to improve the situation of developing countries by granting lighter disciplines or increasing their “embedded expertise” on WTO-related issues. Vineet and Wouters (Reference Vineet and Wouters2021), by comparison, classify S&DT provisions in six categories “1) right to exemptions; 2) right to reduced commitments; 3) right of temporary derogation; 4) right to delayed application; 5) right of presumption; 6) duty on developed Members to refrain from litigation (Vineet and Wouters Reference Vineet and Wouters2021, p. 19).” These categories can be extended by two additional criteria “1) the duration for which the differential treatment is provided; 2) the extent to which reciprocity is exempted, i.e., whether it is a complete exemption or a partial one (Vineet and Wouters Reference Vineet and Wouters2021, p. 20).”

A special debate has also emerged around the multilateral regime’s assessment of Special and Differential Treatment (S&DT) regulation within free trade zones or custom unions. According to General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Article XXIV, Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA)s are subject to rules regarding the scope, ambition, and time schedule of tariff reductions.Footnote 4 While considered exceptions to the Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) principle, these regulations do not relate explicitly to special treatment for developing countries. In fact, only the Enabling Clause of 1979 introduced a more flexible set of conditions for south-south agreements. These differences in attention to S&DT provisions depending on the PTA composition are viewed differently by scholars and experts. For some scholars, Article XXIV limits the negotiation of nonreciprocal North-South PTAs, which excludes the use of S&DT clauses (Yanai Reference Yanai2009). Other scholars share a broader interpretation of Article XXIV, allowing more extensive use of S&DT provisions through preferential frameworks (Brusick and Clarke Reference Brusick, Clarke, Brusick, Alvarez and Cernat2005; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2010; Kuhlmann Reference Kuhlman2021). The approach taken in this chapter follows this second understanding. We also would point out that most PTAs containing different types of S&DT clauses and/or flexibilities have been notified to the WTO and have not triggered a noteworthy controversy.

While uniform S&DT clauses could be expected in multilateral negotiations, negotiating parties in PTAs do not follow a consistent approach. This allows the design of more targeted provisions that account for levels of development and power. Developing countries have displayed different strategies and instruments, leading to more heterogeneity in terms of S&DT across PTAs.

Previous research on S&DT and policy space in PTAs has focused on a variety of instruments across PTA chapters to preserve policy space: the inclusion of safeguards, nonautomatic import licenses, exports’ duty drawbacks, production subsidies, patent restriction in specific sectors, state-owned enterprises, movement of individuals, subsidized credit, local labor requirements, domestic content requirements, as well as technology transfer requirements and exceptional conditions under which some unilateral tariff increases could be allowed (Di Caprio Reference DiCaprio2010; Thrasher and Gallagher Reference Thrasher and Gallagher2010). When policy space is granted in a discriminatory manner, considering the special needs of the less developed signing parties, S&DT comes to the forefront.

Brusick and Clarke, tracing S&DT through regional trade agreements, have pointed to instruments such as “provisions safeguarding the interests of less developed partners; exceptions and exemptions; transitional time periods; technical assistance (2005, p. 167).” Kuhlman (Reference Kuhlman2021), for her part, has emphasized the role of flexibility as a component of S&DT in PTAs. In a recent publication, she observes that PTAs include broader development concerns both in preambular language and/or through operative provisions (i.e., criteria for different treatment among countries according to their needs, transitional time periods, technical assistance and capacity building, and sustainable development).

In brief, existing literature agrees on the necessity to adapt the legal texts of PTAs to accommodate the varying development levels of signatories parties. A diverse array of instruments is employed to achieve this objective, spanning the preamble section and various chapters. There is no single template to refer to S&DT.

5.4 Conceptualization, Methods, and Sampling

Drawing upon these developments on the scope of S&DT, our analytical framework includes traditional “at-the-border” policy space measures (tariff exclusions, transitional periods, rules of origin), as well as capacity-building provisions and any other horizontal or specific measures that imply a nonreciprocal treatment due to development differences.

To map S&DT provisions in PTAs, we propose the following types:

– provisions recognizing the relevance of S&DT treatment or provisions recognizing development-based differences among parties;

– longer transition periods for tariff reduction and for implementing commitments, available only to developing countries;

– provisions granting exceptions, special flexibilities,Footnote 5 and/or special considerations in rules of origin, available only to developing countries;

– provisions providing exemptions to liberalization, such as tariff reduction exclusions, available only for developing countries;

– capacity-building mechanisms and technical cooperation for developing countries or countries with development needs;

– other provisions with nonreciprocal commitments benefiting less developed countries.

Our research follows a qualitative methodology based on manual content analysis. For each agreement, we traced and coded all S&DT provisions along the preambulatory sections, chapters, and annexes. We considered whether the agreements acknowledge development asymmetries among parties and when and how the agreements’ legal texts could be mapped onto one of our categories.

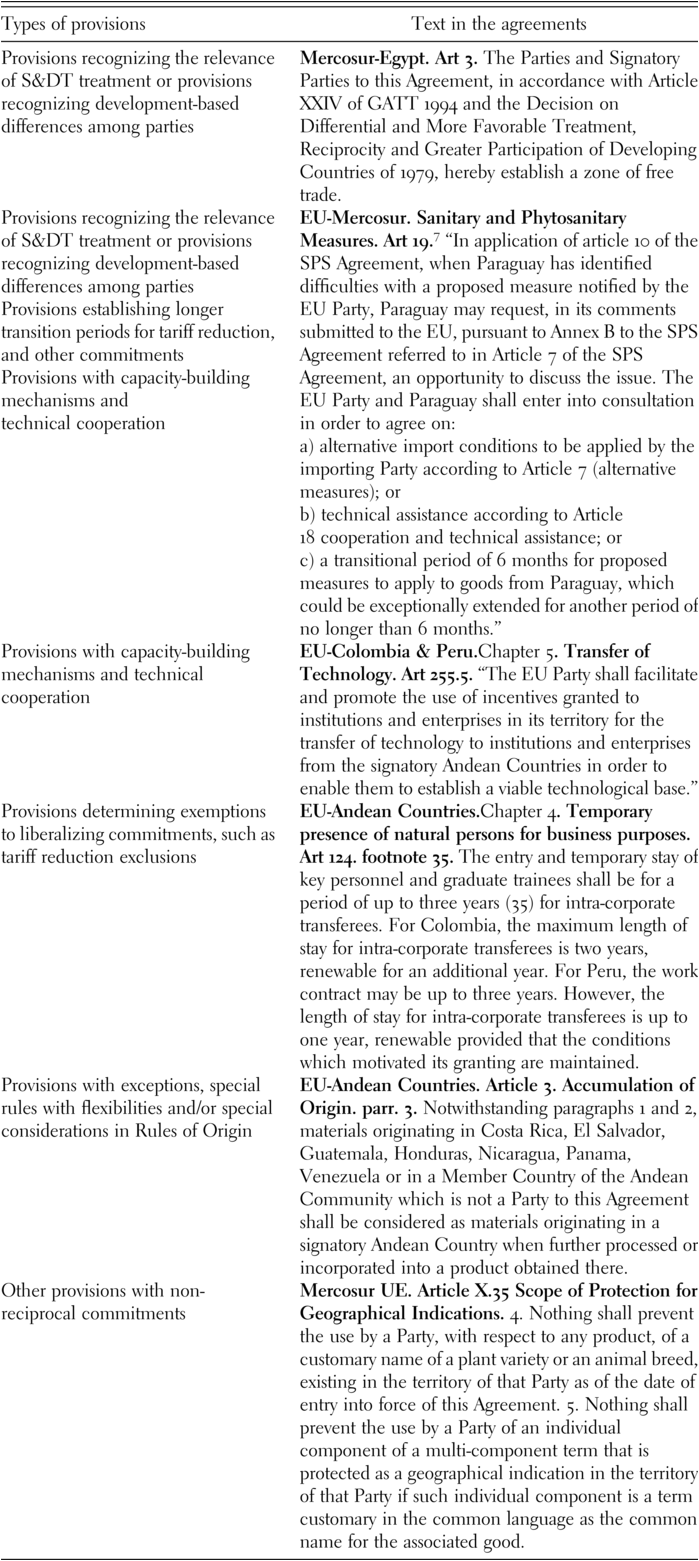

We have paid particular attention to who the beneficiaries are and how binding and legal commitments result (e.g., clauses of best endeavor, soft vs. deep commitments). In some cases, S&DT provisions are found in the body text, while in other cases, S&DT commitments are listed in footnotes or are phrased implicitly and fall into our broader “flexibilities” category. In tariff schedules, the S&DT dimension results from the interpretation of the level of ambition embraced by each party. Some examples of how legal texts are matched with our typology can be found in Table 5.1.Footnote 6

| Types of provisions | Text in the agreements |

|---|---|

| Provisions recognizing the relevance of S&DT treatment or provisions recognizing development-based differences among parties | Mercosur-Egypt. Art 3. The Parties and Signatory Parties to this Agreement, in accordance with Article XXIV of GATT 1994 and the Decision on Differential and More Favorable Treatment, Reciprocity and Greater Participation of Developing Countries of 1979, hereby establish a zone of free trade. |

Provisions recognizing the relevance of S&DT treatment or provisions recognizing development-based differences among parties Provisions establishing longer transition periods for tariff reduction, and other commitments Provisions with capacity-building mechanisms and technical cooperation | EU-Mercosur. Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures. Art 19.Footnote 7 “In application of article 10 of the SPS Agreement, when Paraguay has identified difficulties with a proposed measure notified by the EU Party, Paraguay may request, in its comments submitted to the EU, pursuant to Annex B to the SPS Agreement referred to in Article 7 of the SPS Agreement, an opportunity to discuss the issue. The EU Party and Paraguay shall enter into consultation in order to agree on: a) alternative import conditions to be applied by the importing Party according to Article 7 (alternative measures); or b) technical assistance according to Article 18 cooperation and technical assistance; or c) a transitional period of 6 months for proposed measures to apply to goods from Paraguay, which could be exceptionally extended for another period of no longer than 6 months.” |

| Provisions with capacity-building mechanisms and technical cooperation | EU-Colombia & Peru.Chapter 5. Transfer of Technology. Art 255.5. “The EU Party shall facilitate and promote the use of incentives granted to institutions and enterprises in its territory for the transfer of technology to institutions and enterprises from the signatory Andean Countries in order to enable them to establish a viable technological base.” |

| Provisions determining exemptions to liberalizing commitments, such as tariff reduction exclusions | EU-Andean Countries.Chapter 4. Temporary presence of natural persons for business purposes. Art 124. footnote 35. The entry and temporary stay of key personnel and graduate trainees shall be for a period of up to three years (35) for intra-corporate transferees. For Colombia, the maximum length of stay for intra-corporate transferees is two years, renewable for an additional year. For Peru, the work contract may be up to three years. However, the length of stay for intra-corporate transferees is up to one year, renewable provided that the conditions which motivated its granting are maintained. |

| Provisions with exceptions, special rules with flexibilities and/or special considerations in Rules of Origin | EU-Andean Countries. Article 3. Accumulation of Origin. parr. 3. Notwithstanding paragraphs 1 and 2, materials originating in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Venezuela or in a Member Country of the Andean Community which is not a Party to this Agreement shall be considered as materials originating in a signatory Andean Country when further processed or incorporated into a product obtained there. |

| Other provisions with non-reciprocal commitments | Mercosur UE. Article X.35 Scope of Protection for Geographical Indications. 4. Nothing shall prevent the use by a Party, with respect to any product, of a customary name of a plant variety or an animal breed, existing in the territory of that Party as of the date of entry into force of this Agreement. 5. Nothing shall prevent the use by a Party of an individual component of a multi-component term that is protected as a geographical indication in the territory of that Party if such individual component is a term customary in the common language as the common name for the associated good. |

We designed our sampling strategy to capture various theoretical expectations on the variety of S&DT configurations. First, we selected treaties that vary along the symmetry-asymmetry axes. Therefore, it includes both PTAs with members that are roughly similar in market size and PTAs where parties have significant differences regarding economic indicators and development status. Second, our sample further encompasses treaties that mirror the different waves in the evolving design of PTAs in Latin America, including the “open-type” agreements of the 1990s (Fuentes Reference Fuentes1994), the beyond-the-border agreements characteristic of “twenty-first-century regionalism” (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2021), and those identified as part of a “hybrid” regionalismFootnote 8 (Peixoto and Perrotta Reference Peixoto and Perrotta2018). Third, we know from past literature (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2010; Baccini et al. Reference Baccini, Dür and Elsig2015b) that US-led, EU-led, and south-south agreements tend to have different legal structures and regulatory philosophies (and therefore, different models). To take this into account, the sample includes PTAs with the US, and the EU as partners as well as south-south agreements. Fourth, we consider variation in terms of the overall PTA ambition measured by the concept of depth (Dür et al. 2014), and we allow for potential differences driven by the time dimension by selecting treaties negotiated between 2000 and 2019.

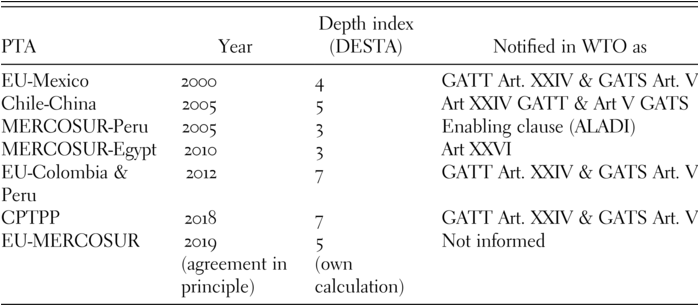

Based on the above selection criteria, we study the following agreements: MERCOSURFootnote 9-EU, Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), EU-Colombia and Peru, MERCOSUR-Egypt, MERCOSUR-Peru, México-EU, and Chile-China FTA (see Table 5.2). We cover nine Latin American countries, individually or grouped in regional integration processes; additionally, we account for both traditional and nontraditional trading partners.

Table 5.2 Selected Latin American PTAs.

This selection covers the so-called two “waves of regionalism” within the region. In effect, during the 1990s and early 2000s, Latin American countries entered several asymmetrical PTAs, following an “open regionalism” model, that is, making agreements with developed countries and abandoning import substitution policies (ECLAC 1994). The EU-Mexico agreement is part of this first group of treaties. The Chile-China FTA, MERCOSUR-Peru FTA, and MERCOSUR-Egypt FTA belong to a different type of agreement. They are part of the south-south agreements wave, a trend observed during the first decade of the 2000s: agreements among developing countries and, in the case of China, including rising emerging powers. The agreements with China and Egypt illustrate FTAs with nontraditional extra-regional partners.

In those same years of the first decade of the 2000s, “twenty-first-century regionallism” gained awareness among trade policymakers in the region. Some countries moved forward into asymmetrical trade agreements that involved beyond-the-border and WTO-plus regulations with extra-regional partners, reflecting the dynamics of global value chains (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2021). Examples include the EU-Andean countries agreement and, more recently, the CPTPP (in which Chile, Mexico, and Peru are involved). The MERCOSUR-EU agreement is considered a case of an asymmetrical trade agreement with an extra-regional partner that includes WTO-plus clauses; however, the fact that it does not include deep commitments in areas such as investment or intellectual property rights has led to its classification as a “hybrid case” (Caetano Reference Caetano2022). Table 5.2 summarizes the characteristics of the selected agreements.

5.5 Where and How Is S&DT Included in Latin American PTAs?

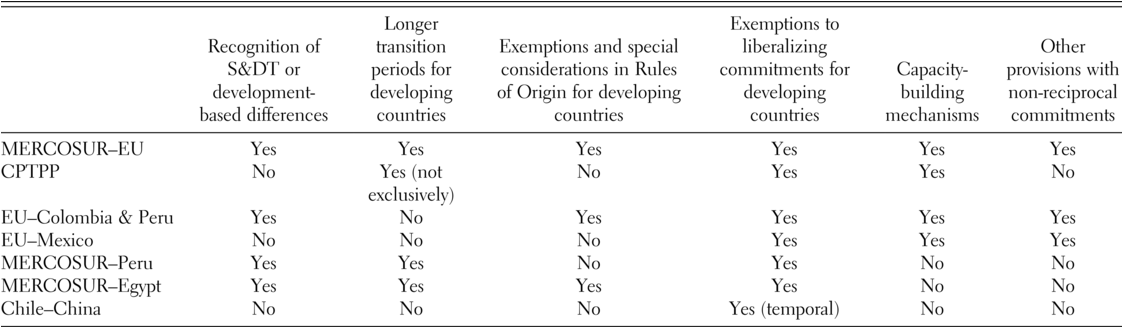

Latin American countries have a long-standing tradition of promoting S&DT at the multilateral level. When it comes to PTAs, our analysis shows interesting patterns of variation. As a first observation, it is noteworthy that all seven agreements analyzed include some form of S&DT provisions.Footnote 10 In the following, we discuss how the six types of S&DT provisions identified in our analytical framework are present in these PTAs, differentiating between asymmetrical and symmetrical (south-south) agreements. Table 5.3 summarizes our findings.

Table 5.3 Special and differential treatment provisions in Latin American PTAs.

5.5.1 S&DT in South-South Agreements

5.5.1.1 Chile-China PTA

Signed in November 2005, the Chile–China FTA was China’s first PTA with a Latin American country. At that time, China had almost no PTAs negotiated and signed, and, therefore, for some observers, one of the reasons behind this agreement was the Chinese government’s objective to gain negotiating experience (DIRECON 2009). Negotiations were short, and although China’s economy was notably larger than Chile’s, they were carried out without any specific consideration regarding leveling the playing field. The first agreement was followed by a supplementary agreement on trade in services in 2010 and by an extended Protocol in 2019.

According to the feasibility study carried out in 2004, this PTA was expected to have a positive impact on bilateral trade and economic welfare, especially in trade in goods and investments (Chilean High Level Study Group 2004). Both parties’ specialization patterns were considered potentially beneficial and complementary for each economy. Therefore, there was no perception of threats to merit the inclusion of asymmetrical in the treaty. Furthermore, from the Chilean perspective, it was expected that “the subscription of an FTA with China would contribute to minimizing trade deviations induced by agreements that Chile has negotiated with the European Union, the United States, and Korea” (Chilean High Level Study Group 2004, p. cxii). Considerations on S&DT were not a priority.

The agreement does not mention S&DT explicitly. Regarding flexibilities, it includes safeguard measures in the trade remedies chapter, and a special exception applies in case of “serious balance of payments and external financial difficulties or threats of thereof” (Art. 102). The treaty foresees cooperation in many areas, such as sanitary and phytosanitary measures, technical barriers to trade, transparency, and small and medium-sized enterprises. The 2019 Protocol added new areas with a cooperation-type clause, for example, e-commerce, competition, environment and trade, and economic and technical cooperation.

Commitments on tariff liberalization are similar for both parties. At the time of entry into force, Chile made 74.1 percent of tariff lines duty-free, representing 50.7 percent of Chile’s total imports from China. In a ten-year transition period, 98.1 percent of tariff lines were reduced to 0, reaching 96.9 percent of Chile’s total imports from China. For China, its initial commitments were smaller, with 28.5 percent tariff lines duty-free, representing 50.9 percent of China’s total imports from Chile. After the transition period, liberalization reached 97.2 percent of total lines in China’s tariff schedule, affecting 99.1 percent of Chile’s exports during 2003–2005.

Within the agreement, there is only one provision in Chapter 1 that introduces a distinct treatment between parties. This provision pertains to an exemption of the interim duty outlined in the “Regulation on Import and Export Tariff of the People’s Republic of China.” According to this provision, “If a Party reduces its applied most favored nation import custom duty rate … after the entry into force of this Agreement and before the end of the tariff elimination period, the tariff elimination schedule (Schedule) of that Party shall apply to the reduced rate.” However, it is essential to note that this obligation does not apply if the reduced rate is stipulated in the aforementioned interim duty (Article 8, Paragraph 3).Footnote 11

5.5.1.2 MERCOSUR-Peru PTA

MERCOSUR and Peru began negotiations for a PTA in the context of the Framework Agreement between the Andean Community and MERCOSUR, since Peru is a member of the Andean Community. Negotiations concluded on 25 August 2005 when parties signed the Economic Complementary Agreement No 58, which entered into force on 6 February 2006.Footnote 12

The agreement’s legal framework is strongly influenced by WTO and the 1980 Montevideo Treaty (ALADI). In fact, information on custom duties modifications among national authorities should be notified to the ALADI General Secretariat (Art. 9). GATT/94 sets a common legal basis for National Treatment (Art. III), disciplines such as antidumping, countervailing measures (Art. 14), custom valuation (Art. 21), intellectual property rights (Art. 32), technical procedures (Annex VIII), sanitary and phytosanitary measures (annex IX). GATT and ALADI also provide exceptions applicable in MERCOSUR–Peru such as the one contained in Article 50 of Montevideo Treaty and Articles XX and XXI of GATT/94 (Art. 10).Footnote 13

As any agreement legally framed within ALADI, it is open to accession by other ALADI members, and there is an obligation to notify in case of negotiations with extra ALADI partners (Art. 40). This agreement has commitments on trade in goods while trade-in services and investments contain best endeavor clauses (Art. 28 to 31). Agricultural and industrial export subsidies are forbidden according to Article 18.

At the request of Peru, the intellectual property chapter recognizes the WTO TRIPs Agreement as the applicable legal framework as well as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Also, Parties agree to develop norms and disciplines to protect traditional knowledge.

There is only one explicit (though not direct) reference to S&DT in the Agreement: Article 1 establishes, as part of its objective to achieve harmonious development in the region, to consider the asymmetries derived from the different levels of economic development. In addition, S&DT is found in the liberalization schedule, where there are more flexible deadlines for Peru in the trade liberalization schedule regarding new products and the so-called ALADI historical heritage (namely, liberalization commitments taken before the agreement).

Beyond that, there is no special flexibility for less developed partners other than specific protection built through rules of origin. However, this underestimates the true extent of S&DT because each signatory party has its own rules of origin profile to protect sectors, including Argentina and Brazil, which are the more developed countries in this trade agreement. In fact, specific transformations, national or regional content, are needed for trading dairy and agricultural products, textiles, multifiber and shoes, machinery and mechanical appliances, electrical equipment, sound recorders and reproducers, televisions, rail transport, automotive sector, and musical instruments among Argentina, Brazil, and Peru. Between Paraguay and Peru, specific transformation and/or requirements are needed for vegetable oil, original yarn for textiles and multifiber, shoes, and metal industrial products. Specific requirements are also needed for trading textiles, multifiber, and shoes between Uruguay and Peru.

5.5.1.3 MERCOSUR-Egypt PTA

MERCOSUR and Egypt started negotiating a PTA after talks held during the G-20 Meeting in November 2003. A PTA was not signed until 2 August 2010, within the framework of the XXXIX Meeting of the Council of the Common Market and the Summit of Heads of State of Mercosur and Associated States. The MERCOSUR-Egypt PTA entered into force seven years after its signature, on 1 September 2017, after the parties completed their internal procedures to ratify the agreement.Footnote 14

The Agreement is legally framed within the multilateral trade rules. It relies on the WTO to define concepts such as tariffs, countervailing measures, antidumping, and safeguards (Arts. 2, 3, and 4), and to regulate disciplines such as quantitative restrictions, national treatment, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, technical barriers to trade, restrictions to safeguard the balance of payments, customs valuation, among others (Arts. 12 to 21). The agreement has the main objective of establishing a PTA following Article XXIV of the GATT and the Decision on Differential and More Favorable Treatment, Reciprocity and Fuller Participation of Developing Countries, known as the Enabling Clause (Art. 3).

Tariff-reduction schedules proceed according to five categories, following two deadlines. The first deadline is the date the agreement enters into force. The second deadline is one year after the agreement enters into force. There is one category for which tariff-cutting does not follow any deadline and depends on the decision of the joint committee. Trade in services is a future goal for negotiations and will proceed within the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) framework.

Apart from the explicit reference in Article 3, S&DT is noticeable in two other sections: trade liberalization schedules and rules of origin. The trade liberalization schedule has a special column for S&DT for Paraguay but is reserved only for two tariff lines related to animal parts products.

Regarding rules of origin, the agreement establishes a different percentage for imported inputs in the case of Paraguay (up to 55% instead of 45% for the rest of the signatory parties). This flexibility reflects the recognition of Paraguay as the least developed country in the MERCOSUR. In addition, for trade between Uruguay and Egypt and between Paraguay and Egypt, the agreement establishes a change in tariff classification if imported inputs do not exceed 10 percent (except for textiles). It is important to note that textiles are quite a protected sector globally and do not usually include S&DT clauses. This is particularly true for Egypt, as a developing country with a long-standing tradition in the textile sector.

5.5.2 S&DT in Asymmetrical PTAs

5.5.2.1 EU-MERCOSUR PTA

The EU-MERCOSUR PTA has a long negotiating history. The Framework Agreement for the negotiation process was established in 1995 but negotiations were not launched before 1999. By June 2019, after twenty years, both parties reached an “agreement in principle” in the so-called trade pillar. Asymmetries between Europe and MERCOSUR are easily noticeable. While MERCOSUR represents barely 2 percent of EU exports, for MERCOSUR countries, the EU is one of their largest trading partners, accounting for more than 16 percent of the total export of goods from the block.

Trade patterns show that EU exports to MERCOSUR are mainly machinery and transport equipment, chemicals, and manufactured goods sectors. In contrast, MERCOSUR’s export basket is concentrated around commodities and low-value-added goods. In addition, whereas the EU is deemed as one of the largest rule makers (“Brussels Effect”), having signed around fifty trade agreements (many of which have strong or deep commitments), this was the first deep agreement for MERCOSUR.

For many years, including S&DT commitments has been a precondition to reaching an agreement strongly advocated by MERCOSUR negotiators. The resulting “agreement in principle” suggests some success in this goal since the legal text contains both substantive and procedural S&DT clauses. Although there is no specific chapter on S&DT, many chapters include some kind of provision where the parties undertake different commitments, agree on differentiated transition periods, allocate exceptions only for MERCOSUR’s members, and/or agree on capacity-building commitments. For some clauses, these considerations apply to all MERCOSUR countries, while in others, they are limited to Paraguay. Nevertheless, differential treatment is given to the EU in one case.Footnote 15

The chapter on sanitary and phytosanitary measures is the sole chapter in the whole agreement that explicitly recognizes “special and differential treatment” (Art. 19). It also includes extended transition periods for implementing sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) provisions in the case of Paraguay. The chapter also incorporates capacity-building provisions and explicitly acknowledges the different levels reached by regional integration processes within MERCOSUR and the EU. From that standpoint, it recognizes the necessity for more flexible regulation within MERCOSUR, urging it to “make its best efforts to gradually adopt, if applicable,” some rules under the agreement.

Longer transition periods are considered in trade in goods provisions, tariff elimination schedules, rules of origin, custom and trade facilitation, and the already mentioned chapter on sanitary and phytosanitary measures.

Tariff commitments reflect each party’s sensibilities: 14.1 percent of MERCOSUR custom duties are eliminated immediately, in contrast with a larger initial commitment of the EU of 74 percent of goods duty-free at the entry into force of the agreement.Footnote 16 After ten years, MERCOSUR reaches 72 percent of liberalization, whereas an additional 18.7 percent of custom duties are reduced in fifteen years, arriving at 90.7 percent of liberalized trade. Only 0.2 percent of goods are subject to quotas, and 9.1 percent of goods are excluded. The EU reaches a 92 percent liberalization in a ten-year transition process and retains partial access to 7.8 percent of goods – including 7.1 percent quotas – whereas 0.3 percent custom duties are excluded.

Notable is the chapter on intellectual property rights, which includes references to the multilateral standards. Although not specifically an S&DT clause, it merits special consideration for developing countries’ IP interests and agenda by preserving multilateral flexibility instead of moving toward a TRIPS-plus agreement. The only TRIPS-plus inclusion in the MERCOSUR-EU Agreement pertains to geographical indications, where a list of European and MERCOSUR products benefit from special protection (the EU has listed 350 and MERCOSUR 220). At the same time, it is noticeable that some capacity-building provisions have been included in this chapter.

Special provisions have been provided only to Paraguay as a less developed treaty partner in the trade defense measures chapter and in the rules of origin provisions. The protocol on Rules of Origin restricts S&DT to specific conditions provided in Annex II (Product Specific Rule of Origin). These are restricted to Paraguay, to a limited set of goods, and with a temporal period not exceeding four years. Finally, there are exceptions or specific regulations for MERCOSUR countries in areas such as government procurement, state-owned enterprises, and export duties.

5.5.2.2 EU-Colombia and Peru PTA

The European Union-Colombia and Peru comprehensive trade agreement was signed in June 2012 (entry into force in 2013). Negotiations were launched in February 2009 and concluded in 2010; later, in 2017, Ecuador joined the agreement.Footnote 17 It is worth noting that signing these PTAs implied the removal of Peru and Colombia from the European Generalized Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP +) provisions. Ecuador was excluded from the programme after reaching the income requirements established by the GSP scheme (Borchert et al. Reference Borchert, Conconi, Di Ubaldo and Herghelegiu2021).

The trade-in goods chapter has a few S&DT provisions. The agreement authorizes Colombia and Peru to apply their price band system in agricultural goods as a special flexibility. Regarding the tariff schedule, S&DT provisions are limited. Before the agreement’s entry into force, 25.2 percent of the EU’s tariff lines were duty-free in contrast to 3.5 percent of Colombia’s tariff lines and 55 percent of Peru’s. As a result of the agreement, in the case of the European Union, additional 6,714 tariff lines (69.1% of the EU’s tariff) have been liberalized for Colombian imports and 6,766 tariff lines (69.65%) for Peruvian imports. After ten years, 95.8 percent of the tariff lines are duty-free for products originating in Colombia, and 94.8 percent for Peru. Nevertheless, 4.2 percent of EU tariffs, representing 12.2 percent of imports from Colombia, remain subject to duties. Regarding EU commitments for Peru, 3 percent remain subject to duties, representing 2.8 percent of imports from Peru.

For the Andean countries, immediate tariff reductions were barely larger. After the agreement’s entry into force 61.1 percent of Colombia’s tariffs became duty-free, reaching 7,143 tariff lines liberalized over a ten-year schedule. 3.9 percent of Colombia’s tariffs remain dutiable, representing 0.6 percent of Colombia’s imports from the EU. In the case of Peru, the initial liberalization was 77.9 percent (55% MFN duty-free plus an additional 22.9%). After ten years, 98 percent of total lines in Peru’s tariff schedule have become duty-free; therefore, 151 tariff lines remain subject to duties (1.5% of Peru’s imports from the EU).

This unbalanced outcome of the tariff reduction commitments was brought up by Malaysia during the presentation of the agreement at the Committee on Regional Trade Agreements of the WTO. However, Colombia and Peru considered the outcome “satisfactory and comprehensive in terms of trade coverage and export and import interests and sensitivities” (World Trade Organization Reference Matsushita, Shoernaum, Mavroidis and Hann2015, p. 2).

In regard to the rules of origin, a notable provision is the one that establishes that goods originating in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Venezuela, or in any member country of the Andean Community which is not a Party to the Agreement shall be considered as materials originating in a signatory Andean country when further processed or incorporated into a product obtained there. There is no comparable reciprocal clause for the EU.

The S&DT principle is formally included and explicitly recognized in the Sanitary and Phytosanitary chapter. Furthermore, this chapter provides an additional six-month transition period as well as technical assistance with specific measures for trade capacity building.

In the trade in services chapter, two provisions recognize a different treatment related to the temporary presence of natural persons for business purposes. In the first one, Colombia and Peru have different maximum lengths of stay for intra-corporate employers’ transferees. In the second one, included in a footnote, both Peru and Colombia limit the application of commitments to major suppliers.

In the chapter covering current payments and movement of capital, a S&DT provision has been introduced as part of the safeguard measures. In addition, in the government procurement provisions, parties included a capacity-building commitment: The EU shall provide assistance to potential tenders from the Andean Community in the EU procurement process.

There are some S&DT provisions included in the intellectual property chapter. These include a differentiated approach to international agreements and their commitments based on the different conditions parties had before the agreements. For instance, whereas the EU “shall make all reasonable effort to comply” with the Patent Law Treaty, the Andean Countries “shall make all reasonable efforts” to accede to it. With regard to patents, the agreement recognizes different level commitments: for Colombia and the EU, data protection for biological and biotechnology products is included, while for Peru, the protection of the undisclosed information of such products shall be limited to TRIPS provisions, with a more restricted scope than for its counterparts. Lastly, the chapter considers a capacity-building commitment regarding the transfer of technology, according to which the EU shall facilitate and promote the use of incentives specific to institutions and enterprises for transferring technology to institutions and enterprises in the Andean Countries.

5.5.2.3 EU-Mexico PTA

The European Union and Mexico reached an Economic Partnership, Political Coordination and Cooperation Agreement in 1997, known as the Global Agreement or EUMFTA, mostly comprising trade in goods liberalization. The Global Agreement was the first transatlantic treaty negotiated by the European Union. Negotiations were concluded following a tight timeframe of less than a year. Both the European Council and the Mexican parliament approved it on March 20, 2000, so the treaty entered into force in July of the same year.Footnote 18

The Global Agreement covers over 95 percent of trade in goods and services. It also provides for government procurement liberalization and for rules on competition, investment, and intellectual property. Mexico agreed to commitments similar to those granted to the United States and Canada under North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), deregulating about 90 percent of cross-border trade.

There are only a few provisions that provide for different treatment in favor of Mexico, with no chapter dedicated to special and differentiated treatment as such. The Global Agreement established a transition period of ten years for all liberalization commitments. In those areas where the Agreement provided for a complete liberalization, the EU had a nine-year transition period, whereas Mexico could use up to ten years (Arts. 8 and 10). It should be highlighted, however, that both countries have excluded significant products from the liberalization schedule.

It is notable that the EUMFTA incorporates a set of social clauses governing areas as human, labor, and environmental rights demanded by the EU, potentially limiting Mexico’s internal policy space. The Global Agreement is comprehensive overall and has improved trade among its parties over the years (Zabludovsky and Lora Reference Zabludovsky and Lora2005, p. 27). However, the agreement’s text only superficially reflects the existing asymmetries between its members.

5.5.2.4 Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

Three Latin American countries are part of the CPTPP: Chile, Mexico, and Peru. This agreement was finalized in 2018 after the US left the original treaty known as Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The CPTPP adopts the TPP text but suspends the application of some clauses that were of great importance to the US. This mega-regional agreement is considered a “new generation” PTA type of agreement due to its economic relevance (regarding its partners’ economic power) and its ambitious commitments. However, on the S&DT dimension, the CPTPP is highly limited. There is no explicit mention of S&DT, and those relevant few are scattered across the treaty parts.

The CPTPP text does not have a distinct set of provisions applicable to developing countries. However, countries such as Brunei, Malaysia, Mexico, and Vietnam have longer phase-in periods before their commitments take full effect. However, the same applies to Japan. Mexico stands out with different liberalization categories for a limited number of tariff lines – those subject to country-specific tariff-rate quotas (TRQs). Furthermore, Mexico’s liberalization schedule applicable to Vietnam is delayed by one year compared to other Parties.

Focusing on services, liberalization proceeds according to negative lists. Mexico and Chile have included some nonconforming measures excluding certain sectors, industries, and practices. For instance, in the case of Chile, the aviation and maritime sectors are exempted from MFN treatment. Aviation, fishing, and maritime services will proceed according to other international treaties. Chile further exempted services related to arts and cultural industries, including audiovisual cooperation.

Concerning state-owned enterprises, the chapter provides a list of nonconforming measures. For instance, in the case of Chile, it retains the ability for national television stations to provide preferential treatment to Chilean content and receive noncommercial assistance; and in the case of Mexico, it retains the ability for the national petroleum company to make purchases on a preferential basis from national firms in its exploration and production activities.

From an S&DT perspective, there are two noteworthy chapters related to development, chapter 21 “cooperation and capacity building” and chapter 23 “development”. The chapter devoted to cooperation and capacity-building set the basis for providing financial or in-kind resources for cooperation and capacity-building activities. In our sample, this is the only agreement that includes financial support for cooperation as part of S&DT provisions. The development chapter also acknowledges the importance of implementing development policies but does not include specific commitments. It is noticeable how this provision does not create any differentiated rights for developing countries.

5.6 Conclusions

Our analysis has shown how S&DT is present in a sample of Latin American PTAs, although through different instruments. The PTA with the most S&DT provisions is the MERCOSUR-EU PTA, whereas the CPTPP and the Chile-China PTAs have the fewest provisions.

First, in relation to the broader literature on PTA design and on S&DT, our research has contributed to highlighting the idea that S&DT does not follow a single template and remains an elusive concept. Latin American countries have resorted to different ways of framing S&DT case-by-case. S&DT, regarding the traditional set of trade policy tools, has focused on excluding certain goods or services in the liberalizing commitments, agreeing on longer transition periods for tariff liberalization or for the implementation of sanitary and phytosanitary provisions. In chapters dealing with “behind the border” regulations, Latin American PTAs show some creativity in how countries sought to preserve their policy space by creating exemptions and carve-outs to regulatory commitments, such is the case in the MERCOSUR-EU PTA. In addition, Latin American cases confirm some of the expectations found in the literature (Di Caprio and Amdsen Reference Di Caprio and Amsden2004; Peixoto Reference Peixoto2010), according to which S&DT in PTAs often focus on chapters such as rules of origin. Our work shows that, at least in the Latin American PTAs we analyzed, this approach is aimed at preserving policy space for particular industrial products or regional value chains. Furthermore, we found that capacity-building mechanisms and technical assistance are a type of S&DT that takes place in asymmetrical trade agreements involving developed and developing countries but not in south-south trade initiatives.

Second, our analysis illustrates that the inclusion of S&DT clauses depends on at least two key factors: whether or not development was framed as an important issue during the negotiating process, and the level of asymmetry among parties. S&DT appears more prominently in cases where development-related concerns are part of the negotiations. Alternatively, when the parties do not frame the agreement as involving asymmetries and/or do not include development-related concerns, S&DT provisions are largely absent. It is striking to note that agreements involving developing countries appear not to take into account south-south asymmetries as much as expected.

Third, regarding who benefits from S&DT, we found that PTAs in Latin America follow a “list approach” to grant access to these provisions. S&DT was attributed to particular countries that were identified as beneficiaries in the exceptions, flexibilities, or carve-outs contained in the different chapters. S&DT did not follow a “pre-defined criteria approach”. This is a practice even in south-south agreements where S&DT applied relatively more to less developed members such as Paraguay or Peru. This way of attributing S&DT departs from multilateral S&DT definitions and other PTAs, such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).Footnote 19

Overall, S&DT remains an elusive concept. The actual practice of S&DT in PTAs looks more like a patchwork of clauses, exclusions, and text interpretations rather than a systematic, regular, consistent, and cohesive set of principles and clauses. There are no specific chapters that group these provisions together. The challenge is how to conceptualize and recognize them to allow for a proper assessment of their extent and importance. The analytical framework presented in this chapter is a first step in this direction. Our analysis can also inspire the development of automatized content analysis strategies. The next steps would be to look beyond Latin America to explore whether there are important regional differences and to evaluate the impact of S&DT clauses. We know very little about how these provisions are used and their effectiveness. Are principles more consequential than individual commitments? For instance, does the decision not to extend the duration of patent protection have a larger impact than a cooperation principle? These and other questions remain to be tackled to understand better how trade liberalization and S&DT can go hand in hand to support development.