A few months after his parents decided to take the remigration premium and move their family back to Turkey, seventeen-year-old Metin Yümüşak took a sixteen-hour bus ride from Istanbul to the West German Embassy in Ankara and begged for permission to return. But this time, “returning” meant the opposite: leaving Turkey and going back to West Germany. Born and raised in Germany, Metin was barely familiar with Turkey. He struggled to speak Turkish, and he knew the country only from his summer vacations. Though he had hoped to attend one of Turkey’s several elite German schools, he had been rejected amid the surge in applications during the mass exodus of Turkish families in the summer of 1984. After waiting two hours at the embassy with all his documents, however, Metin’s “world collapsed” when his request for a residence permit was categorically denied. “A permanent return to Turkey is permanent,” snarked the consular official. Perhaps, she insisted, Metin should have thought about that before he made his remigration decision. “It was never my decision!” Metin cried.Footnote 1

Outside the embassy, Metin had many supporters on his side. Not only did his German principal and teachers write him glowing recommendations, but the donors of his school in Bochum agreed to pay all his living expenses.Footnote 2 With his teachers’ lobbying via letters and phone calls, Metin’s case made it all the way up the governmental hierarchy. Karl Liedtke, a member of the federal parliament from Bochum, implored Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher to grant an exception.Footnote 3 Upon glancing at Metin’s file, one of Genscher’s staffers marveled that the boy spoke “excellent German” and had a “good report card” with especially high grades in German, mathematics, physics, politics, and sports.Footnote 4 A higher-ranking official agreed, praising Metin as “overwhelmingly integrated into the German environment,” but admitted that his hands were tied: the law was the law.Footnote 5 The only way to make an exception might be to classify Metin as a professional trainee rather than a student, but even so, both the municipal Foreigner Office of Bochum and the Interior Ministry of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia would need to grant permission. The paper trail ended there, leaving Metin caught in “the eternal back and forth” and worried that he would “screw up” his life in Turkey.

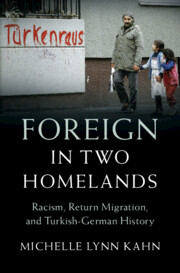

For Metin and the thousands of children and teenagers who returned to Turkey with their parents during the mass exodus of summer 1984, the very concept of “return” was fraught. Though labeled “return children” (Rückkehrkinder; kesin dönüș çocuğu) in both countries, many viewed this category as frustratingly inaccurate. At stake in the notion of “return” was not only the physical direction in which they were traveling but also the very meaning of “home” and the fundamental question of identity (Figure 6.1). Whereas children who had spent most of their childhood in Turkey typically viewed the journey as a homecoming, those born and raised abroad like Metin often considered West Germany their home. Turkey, by contrast, was the faraway homeland of their parents, which they knew only from family stories and their limited experiences on their summer vacations. With this variety of experiences, the rigid categories used to describe migration fall apart: for many children of guest workers, leaving West Germany in the 1980s was not a return or a remigration, but rather an immigration to a new country as emigrants from West Germany.

Figure 6.1 A young Turkish child in West Germany waves the Turkish flag – a symbol of his identity and connection to his home country, 1979. © Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy Stock Foto, used with permission.

The struggle of these archetypical “return children” was especially pronounced because they also bore the burden of another label: “Almancı children,” or “Germanized children.” As over 100,000 children set foot in Turkey in 1984, abstract anxieties about their cultural estrangement and Germanization became concrete. The Turkish media regurgitated exclusionary tropes with new vigor, reporting with both indignation and sympathy on the rowdy, undisciplined, and sexually promiscuous “lost generation” who barely spoke Turkish and had abandoned Islam. The Turkish government, having spent a decade opposing guest workers’ return migration and doing next to nothing to promote “reintegration,” was utterly unprepared to deal with the influx of Germanized children. To “re-Turkify” them, the Turkish Education Ministry scrambled to haphazardly implement “integration courses” (uyum kursları) to prepare them both linguistically and culturally for the coming school year. By bombarding students with nationalist narratives, on the one hand, and failing to address the students’ actual needs, on the other, these courses inadvertently reinforced the very “problem” they attempted to solve.

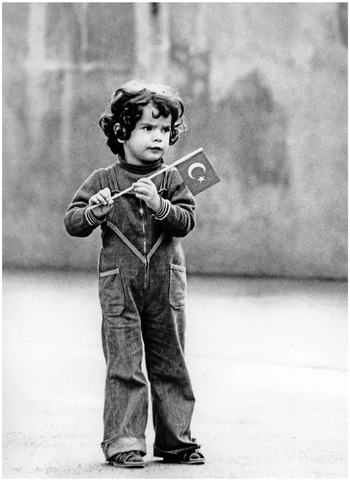

Although West German policymakers initially delighted in exporting the burden of integrating these children and teenagers to Turkey, they soon developed sympathy. Sensationalist reports of Turkish teachers’ psychological and physical abuse villainized Turkish parents for uprooting their children from comfortable lives in Germany and forcing them against their will into a dangerous unknown. Amplified amid criticism of Turkey’s authoritarianism following the 1980 military coup, these reports became new ammunition with which to condemn Turkish migrants, as they reinforced the binary assumption that West Germany was “free,” “liberal,” and “democratic,” while Turkish culture was “authoritarian,” “backward,” and “incompatible” with Europe. Though often twisted in the service of racism, expressions of sympathy for the children’s plight compelled a rare relaxation of West German immigration policy. In 1989, just five years after kicking them out, Kohl’s government permitted the children to return once again – this time, not to their parents’ homeland but to the one that many considered their own: Germany (Figure 6.2). Unfortunately for Metin, his petition to the embassy came five years too early.

Figure 6.2 Cartoon depicting a distressed “return child” (Rückkehrkind) forced to remigrate to Turkey with his parents, 1989. The division of the child’s body into black and white represents his identity conflict as both Turkish and German – or for many children, as neither Turkish nor German.

“Re-Turkifying” Germanized Children in the 1970s and 1980s

“Turkey is foreign to me,” wrote the Turkish poet Bahattin Gemici, reflecting on the collective sorrow of archetypal return children. “I couldn’t even get used to the toilets there. And haven’t you heard what they say about me? Some said that I have become irreligious in Germany. Others have laughed about the way I speak. In reality, I am a German Turk. Papa, please let me stay here. I do not want to go to Turkey.”Footnote 6 Filled with sorrow and desperation, this poem is a reminder of how deeply the everyday lives of young migrants were impacted by top-down return migration policies. Beholden to their parents’ decisions, children generally had minimal say in the difficult question of whether to stay or to leave. Yet they were often the ones hit hardest by the challenges of reintegrating.

From the 1973 recruitment stop through the mass exodus of 1984, 43 percent of the migrants who left West Germany and returned to Turkey were children and teenagers under eighteen years of age.Footnote 7 Numbering at over half a million, they either returned with their parents or, like many “suitcase children” (Kofferkinder), were sent to live with grandparents or relatives. Just like the number of returning guest workers, the annual number of children returning to Turkey peaked in 1984, since guest workers who accepted the West German government’s 10,500 DM remigration premium had to take their spouses and dependents with them, receiving an extra 1,500 DM per underage child. Although guest workers who took the early social security contributions were not beholden to this regulation, they typically returned with their entire families.

Just as there was no singular “second generation,” so too was there no singular experience for children who returned as part of the mass exodus of 1984. Their experiences differed based on their age and gender, the country in which they were born or spent most of their lives, and whether they returned to cities or villages (Figure 6.1). While these differences shaped the children’s attitudes toward and experiences of return migration, both countries’ governments and media tended to homogenize them and to perpetuate the stereotype that the children were both threats and victims in need of assistance. The Turkish government, having opposed return migration and done nothing to assist children who had returned in the previous decade, now scrambled to deal with this “threat” head-on. For the Education Ministry, the challenge was clear: reintegrating this unwanted mass of Germanized children would require re-Turkifying them – turning them back into Turks.

More than their parents’ struggles with unemployment and racism, the experiences of the children and teenagers who returned in 1984 called into question the already contested “voluntariness” of the remigration law. The vast majority of these so-called “return children” had little to no say in the decision and, in many cases, felt that their parents had forced them to return against their own will. This sense of an involuntary return was captured in a prominent 1984–1986 sociological survey of returning children and teenagers of all guest worker nationalities who had been born in West Germany or spent most of their lives there. Approximately one-quarter had wished to return to Turkey, while two-thirds reported that they had been “required” to return with their families or had “not opposed” their families’ desire to return.Footnote 8 While only two percent of respondents used the term “forced” explicitly, the West German media sensationalized the idea of a forced return and portrayed the children as victims of their parents’ decisions. Such rhetoric downplayed West Germans’ complicity in kicking out the Turks by deflecting guilt onto migrant parents for having forcibly removed or even “uprooted” their children.

For many children and teenagers, the prospect of returning to Turkey was connected not only to everyday concerns about their families, social lives, and schools, but also rooted in fundamental questions of identity: where did they feel most comfortable, and which country did they consider “home”? Those who had grown up in Turkey and had migrated at an older age to Germany sometimes considered Turkey their home and looked forward to returning. In a 2014 interview, Meliha K., who migrated to Germany as a teenager, recalled having been ecstatic when her parents decided to return to Turkey. “I hated it! I just hated it!” she exclaimed repeatedly about her life in Germany as her parents, also at the interview, erupted in laughter. “I don’t even understand how they lived there!” she exclaimed.Footnote 9 Günnür, who grew up in Ankara with her grandparents, also expressed her “antipathy” toward Germany.Footnote 10 When her parents forced her to join them in Germany upon her grandparents’ death, she even went on a hunger strike. For Günnür, the problems stemmed not only from her difficulties speaking German and getting used to a new country but also from her confrontation with “village Turks,” whom she encountered for the very first time in West Germany and against whom she harbored prejudices. “I am not a village girl, I was born in Ankara!” she complained, noting that her only friends were German. After years of isolation due to her inability to interact with Turks “like her” from the cities, Günnür was delighted to return to Ankara in the 1980s.

The experience of leaving West Germany was generally more difficult for children and teenagers who had been born and raised primarily abroad. Many of them considered West Germany “home” and mourned their return to Turkey. “It was the most bitter day of my life,” one girl sobbed, “as I had to separate myself from my friends and from the country in which I was born and raised and that I loved as my homeland.”Footnote 11 Erci E., who migrated to Berlin at age four, explained the distinction: “Germany is my homeland (Heimat), but my country of origin (Herkunftsland) is Turkey.”Footnote 12 This notion of a “country of origin” or, literally translated, “heritage land,” reflected a nostalgia for her parents’ past rather than her own individual rootedness within it. By contrast, many viewed Turkey as a “vacation country,” which had inadvertently reinforced their sense of cultural estrangement. Subject to the watchful eye of the “gossip-addicted” villagers, who chastised her for not wearing a headscarf, another girl “noticed each year more clearly how much she had already become a ‘German’ in the eyes of her countrymen.”Footnote 13

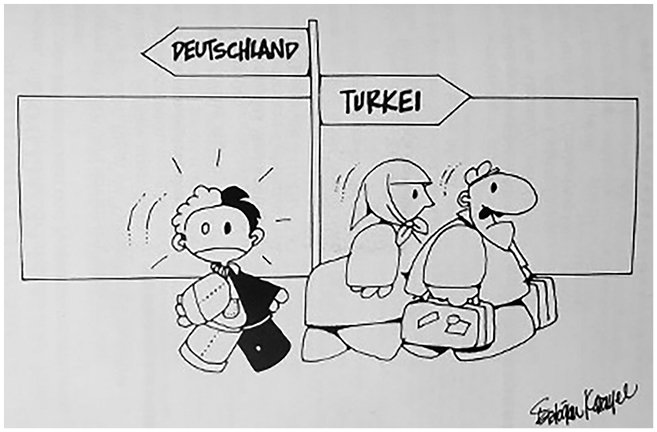

Long derided in Turkey as “Germanized” and suffering from cultural estrangement, the returning children and teenagers struggled with experiences that were as much public as personal. Amid the mass exodus of 1984, Turkish references to “Almancı children” became more frequent and disdainful, often mocking their perceived Europeanization and even Americanization (Figure 6.3). That year, production began on the satirical film Katma Değer Şaban (Value Added Şaban), starring comedic actor Kemal Sunal as a teenager named Şaban who returns to Turkey after spending his childhood with relatives in West Germany.Footnote 14 Immediately, the audience sees Şaban as an object of ridicule. He arrives at the Istanbul airport sporting an outlandish outfit influenced by the 1980s punk music scene – an uncommon sight in Turkey at the time, despite the subculture’s popularity in the United States and Europe. His hair is partially shaved and dyed in splotches of green, blue, and purple. He sports a flashy red turtleneck, tight black leather pants, knee-high boots, a metal-studded vest, a gold earring, and a Mercedes-Benz logo on a gold chain around his neck. When greeting his father, he pulls out a guitar adorned with stickers of rock bands and sings an improvised rock song whose lyrics are a mixture of German, French, and Turkish. “Hallo Papa! Bonjour Papa!” he belts, before switching to poorly accented Turkish. Neighbors’ disdainful glances and explicit criticism of him as an Almancı turn his estrangement into a joke.Footnote 15

Figure 6.3 Turkish teenagers in denim pants, mocked as “Almancı children” in their home country, mid-1980s. Behind them are posters expressing their interest in American and European popular culture: Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca (1942), Gary Cooper in the western classic High Noon (1952), the American horror film Tarantula (1955), the Bruce Lee film Fist of Fury (1972), Freddie Mercury performing in Queen’s 1977 world tour, Miss Piggy from The Muppet Movie (1979), and the German Eurodisco pop band Dschinghis Khan, which won fourth place at the 1979 Eurovision song contest.

This sense of cultural estrangement was not only a social but also a political problem, particularly in the realm of public education. Schools, in Sarah Thomsen Vierra’s words, were the primary institutional sites where Turkish children “began to learn what it meant to be German,” as they interacted on a daily basis with West German teachers, classmates, and state curricula.Footnote 16 As Brittany Lehman has shown, migrants’ home countries also intervened to varying degrees in their education, often leading to transnational tensions.Footnote 17 Brian Van Wyck has traced this involvement to 1972, when, in cooperation with the West German state governments, Turkey began implementing preparatory classes taught by Turkish teachers sent from Turkey.Footnote 18 Because guest workers were still understood as temporary residents at the time, these courses aimed less at integrating students into West Germany and more at preparing them to reintegrate into Turkey. With great leeway to develop their own lessons, teachers sent from Turkey generally highlighted the Turkish language, geography, history, and culture, and decorated their classrooms with nationalistic symbols such as Turkish flags and Atatürk portraits. Quickly, however, the teachers realized that replicating the content and pedagogy of Turkish classrooms did not work well with migrant students, who spent most of their day with German teachers. In explaining the pedagogical differences, observers noted that the disciplinary practices, rote memorization, and lecturing that prevailed in Turkish classrooms contrasted with West German teachers’ interactive and student-centered pedagogy.

By the late 1970s, however, West German officials lamented that efforts to prepare guest workers’ children for their return to Turkey were failing. The Foreign Office was particularly alarmed by a 1977 sociological survey conducted in Izmir that interviewed Turkish teachers about their experiences teaching middle school students who had returned from West Germany. Overwhelmingly, the teachers complained that the students “destroy classroom dynamics” by making rude remarks and forgetting to bring their books.Footnote 19 The problems were most apparent in German foreign language courses, where returning students allegedly acted like “little know-it-alls” and flaunted their near-native mastery of the language in the faces of their Turkish teachers, many of whom had never been to a German-speaking country.Footnote 20 Classroom conflicts were compounded by fundamental differences in the two countries’ public education structures. The Turkish government’s requirement that children graduate from a Turkish elementary school before being permitted to attend middle school (orta okul) meant that children returning with insufficient Turkish language skills were frequently held back for as long as three years.Footnote 21

One way to avoid the language barrier was to attend an elite private or special public school with German as a partial language of instruction. The most prestigious was the German High School (Alman Lisesi), a private secondary school in Istanbul’s wealthy district of Beyoğlu founded in 1868 to educate the children of German merchants, diplomats, missionaries, and cultural figures living in the cosmopolitan Ottoman city.Footnote 22 Located just three miles away was the public Istanbul High School (Erkek Lisesi), which received substantial financial and administrative support from the West German government and had taught mathematics and science courses in German since the 1910s. The latter was one option among the Turkish government’s slate of elite merit-based Anatolian High Schools (Anadolu Lisesi) that, despite their name, were located in major Turkish cities. Yet West German officials knew that such schools, with a capacity of only 1,000 students each and with a notoriously rigorous nationwide admissions exam, could not accommodate a large influx of returning students.Footnote 23 The schools’ location in a few select cities also meant that children who returned elsewhere – particularly, as most did, to villages and small towns – would remain unserved.

Motivated by these concerns, in November 1977 the West German Foreign Office reached out to the embassies of all guest workers’ home countries to ask about any projects currently in place for facilitating the reintegration of guest worker families and offering bilateral cooperation on the matter.Footnote 24 Several countries already had projects underway. Greece had made the most progress, with a designated Reintegration Center for Migrant Workers with branches in both Athens and Thessaloniki set to open a few months later.Footnote 25 Although the Greek Reintegration Center was not government operated (it was funded primarily by the Greek Orthodox Church in cooperation with the Protestant Church of Germany), it was a solid step toward studying the problems of return migrants and offering them legal and practical advice. The West German Foreign Office also touted its financial support for the Association for Greek-German Education in Athens. The association planned to implement a pilot project in a small local private school attended primarily by returning guest worker children and children from Greek-German mixed marriages, which would supplement the regular curriculum with German lessons.Footnote 26

The Turkish government, however, could not name a single organization, governmental or otherwise, that aided returning workers and their children. Turkish officials’ disinterest in assisting returning guest worker families was consistent with their concurrent lack of cooperation with West Germany’s proposals for facilitating the economic and professional reintegration of returning guest workers, owing to their financially based opposition to return migration. West German diplomats complained about a similar nonchalance in discussions of the educational reintegration of migrant children. According to one West German internal memorandum, Turkish embassy officials could provide no “reliable” information about the number of “returning children,” and a follow-up conversation at the Education Ministry revealed that “they do not even see it as a problem.”Footnote 27 To the West German government’s dismay, Turkish education officials had also rejected a proposal by the prestigious Istanbul High School, which envisioned an admissions process that ranked returning children according to their success within the West German education system. Turkish officials balked at the suggestion and, as a result, only seventeen of the ninety-three returning children and teenagers who had applied in the previous months were accepted, even though in most cases their knowledge of the language was “more than sufficient.”Footnote 28

The West German government also encountered difficulties in its quest to send German teachers to educate return migrants in Turkey’s German-language schools, a plan that both countries’ education ministries had been discussing since the mid-1970s. Although both sides had agreed to the sending of two German teachers to the Anatolian High School in Izmir for the 1979/1980 school year, the Turkish government’s “strict adherence” to the extensive review of visa application and work permit materials had made the process “exceedingly difficult” and even “impracticable.” Even though the West German government had sent the required documents six months ahead of the start of the school year, the teachers’ work and residence permits had not been granted by mid-summer. Because of the uncertainty, the West German state authorities gave up on the idea and placed the two teachers in West German schools.Footnote 29

The Turkish government’s unwillingness to develop programs for reintegrating migrant children reflected the overall shift of the late 1970s, when officials sought to prevent the guest workers’ return for economic reasons. As Turkey’s economic crisis worsened and as both countries realized that guest workers were deciding not to return to Turkey, the goal of preparing the students for their return and reintegration receded. As West German Foreign Office officials concluded, “The Turkish government, which until recently had demanded that equal emphasis be placed on the integration of Turkish children into the German school system and on their simultaneous preparation for the smoothest possible reintegration [in Turkey], is now increasingly focusing on the desire for integration.”Footnote 30 Just as in the case of guest workers’ professional reintegration, the Turkish government came under fire again for its unwillingness to assist the children. In 1978, Cumhuriyet complained that the Turkish government was only interested in the guest workers’ remittances and therefore had abandoned the children, who were “heartbroken,” unable to speak either language, and mistreated as the “stepchildren of Germany.”Footnote 31

With the September 12, 1980, military coup, the new Turkish government intensified its efforts to influence the education of Turkish children abroad, particularly in the realm of religion. This emphasis reflected the military government’s broader strategy of achieving unity and stifling left-wing and Kurdish dissidents by reframing national identity in terms of Turkish ethnicity and Sunni Islam. Reflecting this “Turkish-Islamic Synthesis,” as the government called it, religious education became part of the public school curriculum, with an exclusive emphasis on Sunni Islam and on portraying “patriotism and love of parents, the state, and army” as a “religious duty.”Footnote 32 The coup also ushered in a heightened interest in influencing Turkish citizens abroad, whom – with the exception of leftists, dissidents, and ethnic minorities – the military government considered part of the national community. This commitment was codified in the 1982 constitution, which for the first time pledged the state’s responsibility to “ensure family unity, the education of the children, the cultural needs, and the social security of Turkish citizens working abroad” and, crucially, to “safeguard their ties with the home country and to help them return home.”Footnote 33 Although the government blatantly contradicted this pledge by continuing to oppose guest workers’ return migration, its political interest in maintaining their connection to Turkey remained strong.

The Turkish government’s new prerogative, besides attempting to oust leftist Turkish teachers from their jobs at guest worker children’s preparatory schools, was to promote religious education in West Germany through Koran schools. As Brian Van Wyck has explained, Koran schools in West Germany initially existed relatively independently with little influence from Turkey’s secular-oriented government and were organized by Turkish religious groups such as the Süleymancı and Islamist political parties such as the National Salvation Party (Millî Selâmet Partisi, MSP) and far-right MHP.Footnote 34 During the late 1970s, as Europeans increasingly viewed Islam as an impediment to guest workers’ integration, West Germans began condemning Koran schools as promoting far-right Turkish nationalist ideologies, harboring ties to the MHP’s paramilitary Grey Wolves, and abusing their students through corporal punishment. Yet, after the coup, the Turkish government viewed Koran schools as venues for exporting the Turkish-Islamic Synthesis and politically influencing the diaspora. Supported by the West German government, which welcomed the intervention to regulate Islam, Turkey sent state-supported Muslim religious leaders (imams) to West Germany to lead prayers at mosques and teach at Koran schools.Footnote 35

But amid the mass exodus following the 1983 remigration law, as tens of thousands of “Germanized” children and teenagers were poised to return to Turkey for the 1984/1985 school year, the Turkish government was confronted with the reality that manipulating their education in West Germany was not enough. After years of doing virtually nothing to assist them, officials in Ankara now grappled with a question that struck at the core of the postcoup conception of national identity: How, after excessively integrating into Germany, could this “lost generation” of Almancı children – stereotyped as speaking insufficient Turkish, having little knowledge of Turkish culture, and abandoning their Muslim faith – be re-integrated into Turkey? Based on previous reports, the Turkish government knew that the children could not simply be dropped into regular classes. Instead, before they were ready to join regular classes, the children desperately needed an orientation to life in Turkey – better considered as a crash course in re-Turkification. During the summer of 1984, education officials scrambled to implement what they called “integration courses” (uyum kursları), intensive six-week summer programs for the children of returning guest workers that aimed to prepare them for Turkish schools. Though framed primarily as language classes, the courses had an ulterior motive: teaching Germanized children how to be “real Turks.”

Ideologically charged, the integration courses’ government-mandated curriculum reflected the postcoup conception of a singular national identity that was tied to Turkish ethnicity and Sunni Islam and that villainized subversive outsiders. In his analysis of the special textbook used in these courses, Brian J. K. Miller has emphasized that the Education Ministry explicitly expressed its commitment to assisting the children’s reintegration into the “genuine culture of the motherland.”Footnote 36 Glorifying Kemalism and the foundation of the Turkish Republic, the textbook began with the lyrics of the Independence March (İstiklal Marşı) and featured excerpts from nationalistic poetry and the famous speeches of Atatürk. Amid the coup government’s emphasis on militarism, patriotic lessons on Ottoman and Turkish history were sometimes accompanied by lectures on contemporary “national security” in which, as one student recalled, they were required to memorize “the different ranks of the army and the external and internal enemies of Turkey, who were many.”Footnote 37 Departing from the secular orientation of Kemalism, students also received religious education similar to that in Turkish public schools at the time. The courses also placed great emphasis on imparting cultural norms. As Murad B., a self-proclaimed “suitcase child” recalled, “They were teaching us not only the history of Turkey and rules in Turkey but also how you have to appear in Turkey, how you have to behave in Turkey, and that that is different from how you have to act in Germany.” Most vividly, he was taught to “stand up and kiss the hand of elders” when entering their presence.Footnote 38

Given the Turkish public’s longstanding curiosity about “Almancı children” and the fates of return migrants, the integration courses drew widespread media coverage. In August 1984, the Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet published two front-page, above-the-fold articles on the subject, one week apart (Figure 6.4). With forlorn photographs and quotations from returning students, the articles aimed to attract sympathy. In one article, fourteen-year-old Nuri wondered: “Am I a Turk or a German? I can read neither there nor here … Who will accept me?” Seventeen-year-old Erkan, who had been living in Germany since the age of four, felt self-conscious because everyone was staring at his blue jeans, long hair, and Converse shoes. Sixteen-year-old Oya complained that she and others had been held back for several years. “We are adults, but we are in the same class as small children,” she said. “Everyone makes fun of me.”Footnote 39 The second article attributed these difficulties to their general confusion about life in Turkey, with children rattling off lists of what they sensed as cultural differences: why people honked their car horns so frequently, why the toys broke so easily, why civil servants treated people so unkindly, why the television was so awful, why the Bay of Izmir was so polluted, why no one did their job properly and honestly, and why everyone gave commands without saying “please.” After each student’s quotation, the newspaper editorialized by printing the phrase “I am confused” (şaşırdım). The message was clear: “Germany did not adapt to their parents. Or their parents did not adapt to the Germans. Now they are to be adapted to us … For now, ‘They’re Not Adapting at All.’”Footnote 40

Figure 6.4 Front-page Cumhuriyet article on the struggles of “return children” in the Turkish government’s integration courses, August 14, 1984. The headline states: “They Grew up in Another Country and Made their ‘Final’ Return, Now … They Will Adapt to Us.”

Discussions of the integration courses also reinforced virulent stereotypes that villainized returning students. In an interview with Milliyet, a Turkish teacher who taught one of the integration courses berated them as “rude children without morals and without nationalities.” The problem, he insisted, was not insufficient integration into Germany but rather excessive integration. “They learned the German language like parrots in German schools. They learned their way of life like apes. And now they show up in front of us, scrunch their noses at everything, and look down on us and the ‘native’ peers of their age.”Footnote 41 He placed the blame on the structural discrimination the students faced in West Germany, their internal identity conflict, and their parents’ decisions to return against their will. But he did not end there – he also placed the blame, fundamentally, on the children themselves. Statements blaming the children for the problems of reintegration were even more powerful because they came from respected civil servants, including teachers and principals, who had firsthand insight into the children’s classroom behavior. Moving beyond the echo chamber of rumors into the hallowed halls of the schoolgrounds, negative stereotypes about returning students assumed an air of legitimacy, making the children’s sense of cultural estrangement more potent than ever before.

Overwhelmingly, however, the integration courses failed to accomplish their goals. Conceived and implemented at the last minute, despite ample warning about the imminent mass remigration, the courses were marred by organizational problems. During the first summer that the courses were offered, there were not enough spaces to accommodate the number of interested students. Located primarily in cities, the courses reinforced urban elitism at the expense of serving children who returned to the countryside. Although the programs continued the following summers, attendance dropped. In 1986, only 417 students participated in the courses, which were held in thirteen of the country’s fifty-four provinces. The decrease was attributable not only to the declining number of returning children but also to a lack of interest.Footnote 42 Even after attending the courses, only 43 percent of surveyed students described them as “useful,” and Murad B. had completely forgotten about his integration course until asked about it in a 2016 interview.Footnote 43 Resolving the challenge of “reintegrating” “Germanized” children into Turkish schools and society required much more than a top-down, government-sponsored, six-week crash course in what it meant to be Turkish. As Cumhuriyet put it, “It looks like the battle to ‘reintegrate’ children from other countries and other cultures, where we expect them to fit in with us, will take much longer than we thought.”Footnote 44

Liberal Children in Authoritarian Schools

The failure of the integration courses set up returning children and teenagers for a difficult transition to the 1984/1985 school year and beyond. In the ubiquitous news reports from both West Germany and Turkey, one theme remains constant throughout the 1980s: the contrast between the “authoritarian” school system of Turkey and the “free” and “democratic” school system of West Germany. This binary became the focal point of West German media coverage of the struggles of remigrant children because it reinforced West German beliefs about a seemingly “backward” and “authoritarian” Turkish way of life, ideas that had already intensified following Turkey’s 1980 military coup. When applied to the education of returning children, the liberal-authoritarian binary revealed a paradox in Germans’ attitudes toward Turkish migrants. On the one hand, the general emphasis on Turkish authoritarianism underscored the core belief that the migrants were incapable of integrating into West Germany and therefore should continue to return to their home country. On the other hand, by portraying the children’s reintegration difficulties as the result of their education in a “liberal” German milieu, it exposed the possibility that Turkish children, more so than their parents, might be considered German.

In the context of return children’s education, the liberal-authoritarian binary was fundamentally rooted in an essentialist interpretation of the two countries’ different approaches to pedagogy that was amplified following the 1980 military coup. Since the implementation of preparatory courses for Turkish students in West Germany in the 1970s, West German pedagogues had presented the two school systems as incompatible: West Germany’s preference for student-centered and discussion-based learning allegedly clashed with Turkish teachers’ lecturing and emphasis on rote memorization. Criticism of the Koran schools, though mostly detached from the state and taught by religious educators, reinforced the notion that even secular public education in Turkey emphasized discipline and rigidity to the students’ detriment. The role of education in delineating the sense of cultural difference increased following the 1980 military coup and Europe-wide criticism of Turkey’s slow return to democracy. For West German critics of Turkey, the authoritarian classroom went hand in hand with the authoritarian government. While these binaries were largely media discourses in both countries, they were also prominent in the recollections of the return migrant students themselves, of Turkish teachers and principals, and of those West German teachers who were sent to Turkey to assist in educating returning migrant students.

Following Turkey’s military coup and crackdown on leftists, West German observers harped on the idea that those returning to Turkey, especially migrant youths, were feared by both civil servants and the military as “potential agitators” or “revolutionaries.”Footnote 45 Their education in a “liberal” and “freer” education system would make them prone to ask questions critical of the government, behave improperly, and ultimately rub off on other Turkish students. This discourse was not invented by West German observers but was rather grounded in quotations from Turkish teachers and principals who complained about the students’ lax behavior, lack of discipline, and irreverence. One school director paraphrased in a news report expressed concerns that remigrant children would “shake up schools’ sacred framework of drilling and subordination” because West Germany’s “freer” education system had socialized them to express “criticism and dissent.”Footnote 46 The principal of the İnönü High School in Izmir expressed his difficulties remaining patient when dealing with returning children, who had a lax attitude toward authority figures. “I was walking through the hall, and a girl from Germany came up to talk to me. She linked arms with me and started chatting as if it were nothing. Most of them never say ‘my teacher’ (hocam). We must teach them how one speaks to a teacher. They call the teachers ‘uncle’ (amca).”Footnote 47

In both West German and Turkish news outlets, the figure of the school principal embodied these power dynamics. Equating having been raised abroad with a disease that only a proper Turkish education could cure, one school principal reportedly told the students on the first day of school: “You are from a foreign land. I will make you healthy again.”Footnote 48 In another article, Cumhuriyet reported on the students’ first encounter with the principal of a residential school near Ankara. As the students fooled around during his speech, the principal rattled off a list of restrictions: “There is nothing forbidden here, but there are rules. You are not to exit the dormitories. I am not saying that you may not stroll along the roads and parks, but there will be surveillance and supervision.” The principal emphasized clothing restrictions along gendered lines. “I do not want students wearing blue jeans and going without neckties … Female students will also wear clothing appropriate for students and will be dressed modestly … Say goodbye to your parents. Hand over your earrings and jewelry to them. Straighten up your uniforms. Separate the male and female students.” The students’ immediate reaction reveals their negative impressions of their new schools. “This much discipline is not necessary at all,” a teenage boy named Murat scoffed.Footnote 49

The restrictions on clothing and accessories were among the most controversial, with students complaining that the uniforms stifled their identities. At the time, Turkish public schools required uniforms: girls wore skirts or dresses with done-up hair and no makeup or jewelry, and boys wore suit jackets, neckties, and had very short haircuts. But, as reflected in the cinematic caricature of the Almancı named Şaban as a punk rocker, many teenage boys had grown their hair out long past their chins or shoulders or had pierced one of their earlobes. That was true of Hüseyin, who returned to Turkey from Würzburg in 1984. Despite expressing his punk rock personality aesthetically with long hair, jeans, a military-style jacket, and an earring, Hüseyin was forced to take out his earring to conform to his Turkish school’s dress code. As Die Tageszeitung put it mournfully, “Today, the small hole in his ear remains a reminder of his past.”Footnote 50

While clothing restrictions were the most visible manifestation of control, much of the controversy surrounding the liberal-authoritarian binary centered on classroom dynamics, particularly the student–teacher relationship. West German teachers sent to Turkey to teach returning children articulated the binary most explicitly. In Turkey, complained one German teacher in Istanbul, students’ role required “passively listening to the teaching authority and diligently writing down everything said, learning the content more or less unreflectively by heart, repeating it back as close to verbatim as possible in the exams, neither scrutinizing nor analyzing nor criticizing it, copying down pages from books – whether understood or not – nonetheless presenting it all proudly as accessible facts.” It was clear, she concluded, that “many years of attending a German school can disrupt the usual attitude towards learning in Turkey.”Footnote 51 After spending the 1985/1986 school year at Istanbul’s Üsküdar Anatolian High School, another teacher explained that he had needed to adapt his otherwise “liberal” teaching style. “Even I became authoritarian at this school,” he admitted, calling the school “fundamentally a ghetto”: “It would have been impossible to accomplish anything without disciplinary measures. This school system would never function if all were authoritarian and only one was liberal.”Footnote 52 Another German teacher, about to depart for a year in Turkey, worried whether he would be compatible with Turkish schools and feared aggravating his Turkish colleagues. “I do not want to change my teaching style,” he said, “but I also do not want to cause conflicts. I want to do everything to avoid provoking the Turkish side.”Footnote 53

The notion that Turkish teachers were harsh disciplinarians whereas German teachers were friendly and “liberal” was also common in West German media accounts of the time. A Der Spiegel article published at the beginning of the 1984/1985 school year, which recounted young return migrants’ nostalgia for their German schools and their regrets about returning to Turkey, was tellingly titled “My German Teachers Loved Me.”Footnote 54 Yet the West German media’s emphasis on the idea that German teachers “loved” their students was an overly rosy portrayal that failed to address far more rampant accounts of tensions and abuse experienced by Turkish students in German classrooms. In a short 1980 poem, a fourteen-year-old Turkish boy named Mehmet, who had only spent four years in Germany, complained that his German classmates called him cruel names, such as “camel jockey,” “garlic eater,” and “stinker.”Footnote 55 A sixteen-year-old girl named Nalan complained that her peers even tried to insult her by calling her “Atatürk” and were only nice to her – “for a very short time!” – when she would bring chips and candy to share with them.Footnote 56 In many cases, teachers did not stand up on the Turkish students’ behalf. Yet, by focusing on the positive rather than the negative, West German news outlets could strengthen their arguments condemning Turkish schools to reinforce exclusionary tropes about Turks in general.

Those sympathetic to returning students also assailed the public-school curriculum for reinforcing Turkish nationalism. Die Tageszeitung remarked that, compared with the cautiously muted nationalist spirit of post-fascist West Germany, the requirement to sing the Turkish national anthem at the beginning of lessons was “incomprehensible” to many students and quoted one student who dismissed Turkish schools as “total shit.”Footnote 57 The greatest disconnects occurred in history and geography courses, which touted the accomplishments of Atatürk alongside the centuries-old tales of Turkish military triumph. One student complained, “In history class, we are told only about Turkey. They portray Turkey as a country without negative aspects, as a country that lives in prosperity and affluence. I have had history classes for three years and we have only talked about Atatürk and his reforms. But we also have to know about the rest of the world!”Footnote 58 The Turkish journalist Baha Güngör, who regularly contributed to West German newspapers, concurred: “These young people do not want to know how the Turks won the Battle of Malazgırt in 1071 and why this battle should be so meaningful for Turkey today. They want to know why there is inflation, why Turkish democracy lags so far behind that in Western European states, and why Turkey is so harshly criticized by Europe in questions of human rights.”Footnote 59

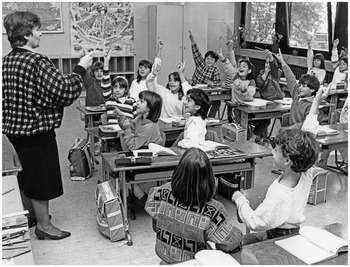

Returning students themselves complained that attempts to deconstruct nationalistic narratives, ask critical questions, and discuss or debate the lecture material were shut down. Alongside the liberal-authoritarian binary, they also invoked the language of democracy and modernity. A teenage boy interviewed for a Turkish newspaper praised the more “democratic” environment that he had experienced in West Germany, where he was allowed to raise his hand, participate, and “contradict” the teachers (Figure 6.5). “Discussion is the foundation of democracy,” he insisted. “One cannot educate through orders. One must persuade.”Footnote 60 Another boy from Nuremberg called his experience at Turkish schools “a type of slavery” and complained that the Turkish education system was “not modern.” “If I want to have a modern education,” he quipped, “I have to go to Germany.” An eighteen-year-old at the private Ortadoğu Lisesi described his school days as psychological torment that was “brainwash[ing]” him into obedience: “All nerves are under pressure … To be able to survive here, one must not speak, not see anything, and of course not hear anything.”Footnote 61 A German teacher who worked with returning children connected this stifling of discussion to the question of Turkey’s status as a democracy following the military coup: “The Turks must learn to handle criticism if they want to be a democratic state.”Footnote 62 Most egregiously, several students flipped the script on Nazi analogies by comparing Turkish teachers to Hitler.

Figure 6.5 Reflecting return migrants’ praise of West Germany’s “democratic” teaching style versus the “authoritarian” education in Turkey, Turkish children in a West German preparatory school eagerly raise their hands, 1980.

The strongest critiques, however, targeted Turkish teachers’ verbal and physical abuse of their students. Halit, a ten-year-old boy whose family came from Fetiya on the Aegean coast, explained the disciplinary differences in Turkey. “The teachers don’t know how to treat people,” he complained. “If you don’t pay attention to something, if you just fool around during the lesson, you’ll just get slapped a couple times.” In Germany, on the other hand, “the teachers would just glare at us and then we were all silent as fish.”Footnote 63 Ayşe, who attended Maltepe Lisesi, revealed that she was “still very afraid of the teachers,” who had often hit her.Footnote 64 Her schoolmate, Ayhan, corroborated her claim: “In Germany, we were always warned: ‘Be careful, when you’re in Turkey, they will make real Turks out of you.’” His fears materialized one day during a geography class. When he could not identify the name of a Turkish city, his teacher slapped him in the face as part of an apparent pedagogical technique: the name of the city, Tokat, means “slap.”Footnote 65 In another article, a Turkish teacher exposed the abuse committed by her own colleagues.Footnote 66 A fellow teacher had publicly shamed a remigrant student as a “beast” for chewing gum during class. When the student responded by calling him a “pig” in German, which required translation by another remigrant, the teacher slapped him and kicked him out of the classroom. Although the teacher had escalated the incident, the disciplinary committee blamed the student.

Often it was not only teachers but also classmates who viewed the returning children disparagingly, reiterating tropes about the migrant children’s excessive freedom and lack of discipline. Directly labeling his peers as Almancı, a student at Istanbul’s Üsküdar Anatolian High School explained matter-of-factly: “They are freer than we are, and their language is ill-mannered and rude. They just have not experienced sufficient care from their parents.”Footnote 67 Many remigrant children found themselves once again subject to their peers’ cruel name-calling – this time, however, from their Turkish classmates. A girl named Yeşim recalled times at which her Turkish classmates had called her a “Nazi.”Footnote 68 Halil, a middle-school-aged boy who had grown up in Hamburg, was taunted as a non-Muslim infidel (gâvur) for having eaten pork in Germany, even though he promised that he never had.Footnote 69 The ostracization from classmates meant that returning children often tended to congregate together and speak German among one another.

Outside school, the children faced similar difficulties that further reinforced preexisting stereotypes about Turkish culture as authoritarian and patriarchal. Reflecting ongoing West German narratives of Turkish women’s victimization at the hands of their patriarchal husbands and fathers, reports on remigrant children drew distinctions based on gender and highlighted the struggles of teenage girls. A 1985 Die Tageszeitung article reported that Turkish newspapers’ frequent criticism of the girls’ allegedly loose morals and sexual promiscuity had affected their daily interactions with men in their home country.Footnote 70 Men of all ages, the article stated, “hit on the remigrant girls in order to go to bed with them.”Footnote 71 Migrant girls’ styles of dress and their refusal to wear headscarves also raised eyebrows within local communities. In one of Gülten Dayıoğlu’s short stories about returnees, a middle-school girl named Yahya becomes the target of local gossip. “Why are her pants so short and tight around her bottom? People would even be embarrassed to wear that as underwear!” the neighbors complain. The gossip takes an emotional toll on Yahya. “I am like a prisoner in the village,” she explains. “When I go outside, everyone looks at me. There is nowhere to go, no friends. I am going crazy trapped at home.”Footnote 72

Many girls encountered harsher restrictions in Turkey since their parents wished to respect local gender norms and fit in among their neighbors. When speaking to journalists about life in their parents’ homeland, they often invoked the language of “freedom.” Derya Emgin, whose family remigrated from Heidelberg, recalled feeling very “aggressive” toward her parents. “I did not want the boys on the street to think of me as an ‘easy girl,’” she explained, and “I complained to my parents that I could have had a freer life in Germany.”Footnote 73 Zemre B. reported a similar experience: “In Germany, I played volleyball very often, and we would go to the disco at night. Here I can’t be seen with a boy at all and, if I were, all hell would break loose.”Footnote 74 Though less commonly reported, some girls experienced new freedom of mobility. Hülya, who grew up in Siegen and accompanied her parents to Gelibolu at age fifteen, quickly realized what was not permissible, such as “smoking inside a store or smoking outside in front of my parents or kissing a guy.” But Hülya’s parents did permit her to go to Turkish discos, a privilege denied to her in West Germany. She attributed the shift to her parents’ belief that their home country’s gender relations, specifically the pressures placed on Turkish men, would prevent them from making a move on her. “Here everyone knows that the girls have to be virgins. If they were to sleep with a girl, they would have to marry her immediately. So, they’re sort of afraid.”Footnote 75

Alarmed by the rise in media attention to the problems of remigrant children, some Germans traveled to Turkey to observe the situation firsthand. In 1986, a group of social workers based in North Rhine-Westphalia went on an expedition to Turkey to report on the experiences of remigrant children and compiled their diary entries and findings in a report aptly titled Almancılar – Deutschländer. The social workers expressed great sympathy. A woman named Anja described an encounter in Zonguldak with a teenager named Hasan, an only child who had lived in Germany from 1976 to 1984 and had returned, in his words, because he “did not wish to destroy his good relationship with his parents by marrying a German.” Although he soon regretted the decision, he could not return to Germany even as a visitor due to harsh visa restrictions. “His life is destroyed,” Anja wrote. “It was another one those depressing experiences that made me feel powerless and sad.”Footnote 76 The impression of the students’ treatment in Turkey was even worse for Monika Joseph, a German teacher who likewise traveled there that year as part of a three-week study trip with a group of her colleagues.Footnote 77 While she was initially excited to learn about the home country of her Turkish students, her observations made her “less tolerant than before,” since they reinforced her disdain for the poverty and religious conservatism of the countryside. A village near Hatusha, she complained, did not even have a chalkboard, and she had a “not so nice” conversation with a local religious teacher (hoca). Most appalling to her were the regulations of a school in the Central Anatolian province of Kayseri, where female students allegedly received a fine or even a short prison sentence for removing their headscarves.

Following widespread reports of the children’s difficulties, local-level initiatives began cropping up to ameliorate their plight. In 1987, Canan Kahraman, who had spent fifteen years in West Germany, founded the Istanbul-based Culture and Assistance Association for the Children of Remigrants (Kultur- und Hilfsverein für die Kinder von Remigranten). Her motivation to found the organization stemmed from the “depressive phase” that she had endured when returning to Turkey in 1975. “It was a difficult time for me,” she admitted. “No one was there to show me the way, which would have helped me very much. I at least needed someone to whom I could have told my problems.” Kahraman envisioned the organization as a space for the children, teenagers, and young adults to candidly discuss their challenging experiences and to attend film screenings, museum exhibitions, concerts, seminars, and language courses.Footnote 78 Psychologists and therapists also developed programs for the children. The first was founded in 1989 as a cooperation between the German Culture Institute (Deutsche Kultur-Institut) in Istanbul and Ali Nahit Babaoğlu, director of the Bakırköy Psychiatric Hospital, who had spent fifteen years living and researching in West Germany. The goal was to create a space where local psychiatrists could meet individually with the children and, in rare cases, prescribe medication. The Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung praised the initiative for assisting children “who have found themselves psychologically in severe distress” and who “have until now surrendered to their mostly tragic fate and therefore have ended up at emotional dead ends.”Footnote 79

The Right to Return – Again – to Germany

With all the attention to the children’s problems, it came as no surprise that the Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) chose to produce the low-budget 1990 feature film Sehnsucht (Yearning). A joint production by Turkish writer Kadir Sözen and German director Hanno Brühl, the fictional film follows the teenage Hüseyin and his younger brother Memo as they accompany their parents to a small town near Izmir after growing up in Cologne. Upon the brothers’ arrival, the townspeople treat them like outsiders. Hüseyin, who works at a small grocery store, endures the constant berating of his boss, and Memo has trouble at school. The teacher yells at him in front of the other students, complaining that he is “undisciplined” and “needs to learn respect.” Walking home from school and on the soccer field, the other students tease Memo, using the word Almancı. Relations within their nuclear and extended family are also strained. As a punishment for Memo’s poor grades and his inability to speak proper Turkish, their father sends the boys to pick cotton. Their uncle, who owns the cotton fields, screams at them for their apparently poor work ethic. “Did you learn that in Germany? Lazy twerps!” Ultimately, the brothers decide to run away, illegally cross the West German border, and reestablish their lives in Cologne.Footnote 80 Yet their plans are foiled by their lack of entry visas. Although the brothers had grown up in West Germany, the local Foreigner Office declares them illegal and orders them to return to Turkey.

Premiering at the First European Youth Film Festival in Antwerp and airing in the primetime Friday night slot on West German television, the film garnered further West German sympathy for the plight of remigrant children.Footnote 81 In the words of one reviewer, it offered an “authentic” portrayal of the children’s “inner turmoil” as remigrant youths. “For many,” she wrote, “the country that most know only from stories and the annual vacation, becomes a nightmare.”Footnote 82 The reviewer also noted that the film had a “pedagogical” function that stood to influence policy. The timing of the film’s production, the late 1980s, coincided with political debates about whether children who endured hardships after unwillingly returning to their parents’ homeland might one day be granted a “return option” (Wiederkehroption). This time, however, the return would mean going back to West Germany, the place they considered home.

The number of returning children who, like the fictional Hüseyin and Memo, yearned to return – again – to Germany was overwhelming. In a sociological survey of returning children between ages twelve and eighteen, nearly half the children said that they were “not satisfied at all” or “partly unsatisfied” with their return, that their lives in Germany had been “much better” or “somewhat better,” and that they would “definitely” or “very much like” to go back to Germany.Footnote 83 Evenly split by gender, these sentiments were especially strong among children who reported having been “forced” to return. Two-thirds cited “major school problems” due to both the language barrier and the school system itself. While this survey did not ask the students about their experiences outside school, their concerns about life in Turkey were multifaceted, involving their social lives, family conflicts, gender roles, and the overall feeling of being ostracized as Almancı. Missing their friends in Germany, with whom they now communicated only by letters or rare international telephone calls, played a major role.

For West German policymakers, a new question emerged: should these children be allowed to return to West Germany? Was there a moral or ethical imperative to alleviate the suffering of these children, whom the government had “kicked out” only a few years earlier and who considered Germany their homeland? These debates largely unfolded along party lines. Kohl’s CDU/CSU-FDP coalition, having expressly excluded a “return option” from the 1983 remigration law, ardently opposed allowing them to return. The SPD and Green Party, long more willing to express sympathy for the migrants, pushed for a return option in the late 1980s.

Discussions surrounding the return option emerged at the same time as some even more controversial debates about whether to grant migrants German citizenship. Germans’ longstanding and archaic racialized notion of citizenship, initially codified in 1913, perpetuated racism and social exclusion by legally classifying migrants as “foreigners.” Permitting them to become citizens, as the SPD and Green Party increasingly argued throughout the 1980s, would serve as an acknowledgment – at least on paper – that they had become part of German society. In 1981, however, the attempt by Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and his SPD-FDP coalition to pass a law that would provide a path to citizenship for individuals born in Germany was silenced by the increasingly vocal call “Turks out!”Footnote 84 Reports on the plight of “Germanized” children who returned to Turkey reinvigorated the debate throughout the 1980s since they opened many Germans’ eyes to the reality that many children identified – and were externally identified in Turkey – as more “German” than “Turkish.” If the children were not able to reintegrate into their own home country, and if their own countrymen treated them so poorly, then where did they belong? Perhaps these children – and maybe even migrants as a whole – not only deserved to live in Germany but also to become German citizens.

These questions were on the Green Party’s mind in the spring of 1986, when the party’s parliamentary faction pressed Kohl’s government to articulate its opinion on permitting returned guest workers – and particularly their children – to move back to West Germany after difficulties “reintegrating.” Did Kohl’s government agree, the Green Party inquired, that West Germany had a “moral responsibility” toward children and teenagers who were either born in or “experienced most of their socialization” in West Germany? What “concrete measures” would the government take to “ease” their situation? Even more controversially, the Green Party asked whether the government would be willing to grant new residence permits for reentry in exceptional cases, such as when parents realized that their decision to return to Turkey was “significantly adversely affecting their children’s future development,” and if the parents were willing to repay the 10,500 DM premium and early social security reimbursement. The Green Party also proposed another exceptional situation that cast reentry into West Germany in a way that detached the children from their parents: could new residence permits be granted to children and teenagers who had spent most of their lives in West Germany, and who before age eighteen had been “forced to leave because of their parents’ decision,” but who wished to return to West Germany after reaching adulthood?Footnote 85

On all counts, Kohl’s government responded negatively and defensively, rejecting the notion that West Germany had a “moral responsibility” toward the children. At fault for their difficulties was not the 1983 remigration law, the government insisted, but rather their home countries’ dire economic problems. Though unwilling to admit that the returning children had integrated into West Germany, the government did acknowledge that they had been passively “affected by our cultural and social environment.” The overall impression was that the government had little interest in assisting the children. As for the controversial question of permitting returnees to reenter the country, the government refused. Even doing so on a case-by-case basis would “effectively result in an unlimited possibility for return.” Flippantly, the government reminded the parliamentarians that the 1983 law had established the infrastructure for advising guest workers before they decided to take the 10,500 DM premium. Parents, in this view, were to blame since they should have been forewarned about their children’s potential struggles.Footnote 86

The push for a return option did not subside, however, and became a hot-button issue in 1988. In March 1988, the SPD parliamentary faction introduced a Law for the Permission to Return for Foreigners Who Grew up in the Federal Republic. The draft law proposed the provision of unlimited residence permits for young foreigners who had completed their education in West Germany or had spent most of their lives there between the ages of ten and eighteen, as long as they applied for the residence permit within three years of their eighteenth birthday. To justify the law, the SPD contended that one-quarter of all returned foreigners were children and teenagers under age eighteen, who were dependent upon their parents’ decisions and had encountered “great difficulties reintegrating into the societal environment of their homeland.”Footnote 87 According to SPD member Gerd Wartenberg, the law fit squarely into West Germany’s integration policy and aimed to “help solve human difficulties and individual fates.”Footnote 88 Yet given the Social Democrats’ status as the opposition party, the proposed law found little traction.

Reforms quickly began at the state level, however. In May and June 1988, the State Interior Ministers of West Berlin and North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) began granting exceptions to young foreigners wishing to return to West Germany, and Hamburg and Rhineland-Palatinate followed suit.Footnote 89 Each state imposed its own guidelines. In West Berlin, for example, foreign children could only return if they wished to complete an educational or professional training program in the state and had submitted their application within three years of their departure from West Germany.Footnote 90 In justifying the reform, NRW Interior Minister Helmut Schnoor (SPD) cited “progressive” and “humane” concerns grounded in “a Christian conception of humanity.”Footnote 91 Many of the children had suffered “tragic fates” and should be allowed to return if “Germany had become their actual homeland.”Footnote 92 The Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger praised Schnoor’s move: “Whoever knows about the tragedies that are occurring in Turkish families who are willing to return or have already returned can only welcome that Interior Minister Schnoor has implemented a liberal rule for the young foreigners.”Footnote 93 The Kölnische Rundschau concurred, noting that “the Federal Republic has a human responsibility toward these young people.”Footnote 94

The tensions between the states’ reforms and the federal government’s obstinacy resulted in a surge in media coverage in the summer of 1988, with reports highlighting individual cases of Turkish teenagers and young adults who had been denied reentry into West Germany. The Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung reported on twenty-one-year-old Tahsin Baki, who had accompanied his parents to Turkey in 1984 following their acceptance of the 10,500 DM remigration premium.Footnote 95 The newspaper explained that his strong Ruhr accent and poor knowledge of Turkish made him an “outsider” in Turkey. Two years later, Baki had returned to his hometown of Gelsenkirchen with a tourist visa and attempted to apply for a residence permit. Despite written confirmation that he had secured an apprenticeship at a pet shop, the local Foreigner Office denied his request. An appeal to the NRW state government proved fruitless, confirming the assessment that Tahsin was in West Germany illegally and faced deportation if he did not return to Turkey voluntarily. After a yearlong battle, the state of NRW finally granted him a limited residence permit in the fall of 1987.Footnote 96 Another well-publicized case was that of Hakan Doğan, who was born in a small town near Bergisch-Gladbach, and who lived there until his family returned to Turkey when he was fifteen years old. Only after public protests and the powerful endorsement of a local government official in Cologne was he permitted to return to his West German hometown. As one headline put it, Doğan was just one of many “young Germans with Turkish names.”Footnote 97

Public opinion further shifted in 1988 with the revelation that several politicians in the governing coalition had changed their stance.Footnote 98 The most prominent was Liselotte Funcke (FDP), the Federal Commissioner for the Integration of Foreign Workers and their Families. Despite having earned the nicknames “Mother Liselotte” and “Angel of the Turks” for the “tolerance and understanding” that she showed toward guest worker families, Funcke had long toed the coalition line on the issue of a return option.Footnote 99 When she visited Istanbul’s Üsküdar Anatolian High School in the spring of 1986, several children had complained to her about their inability to return to West Germany. One boy questioned: “We lived in Germany for fourteen or fifteen years. We have friends and family there. But we cannot travel to Germany. Why?” Another lamented that he required a visa to spend his vacation in the country in which he had grown up and argued that Turkish citizens who had lived in West Germany should receive preferential treatment in immigration policy: “We’re not like the other normal Turks in Turkey. There have to be exceptions for us, right?” Funcke evaded the questions and defended the restrictive policy. Instead, she urged them to use their bilingualism as an “opportunity” and to come to terms with their situation as “migrants” in a globalizing world. “Living abroad is the fate of our time,” she asserted.Footnote 100

But with all the media coverage and studies of the children’s struggles, Funcke changed her position. In October 1988, she made headlines throughout the country when she implored Federal Interior Minister Friedrich Zimmermann (CSU) to include the return option in the ongoing revisions to the Foreigner Law (Ausländergesetz), which would go into effect in 1990. Strategically, Funcke appealed not only to sympathy for the children’s plight but also to the need to standardize state and federal immigration policy. State reforms should apply to the entire country, she maintained, so that the opportunity to return would no longer depend on the state in which a young foreigner had grown up.Footnote 101 To mitigate critics’ concerns, Funcke promised that a federal return option would not lead to a “flood” (Überschwemmung) of foreign children into West German borders. As evidence, she cited a study concluding that, of the 17,000 eligible Turkish youths, only 4,000 would want to take advantage of such an offer.Footnote 102 Despite having submitted her written pleas to Zimmermann, the Interior Minister had not responded.

After nearly a year of discussion, Kohl’s conservative government finally softened its stance. In late December 1988, the Federal Interior Ministry publicized its plans to implement the return option for foreign children who had spent most of their lives in West Germany. The decision, as several news outlets interpreted it, stemmed less from Interior Minister Friedrich Zimmermann’s concern for the children’s plight than from his desire to reconcile state and federal policy and to extend a “signal of goodwill” to the FDP and to certain Christian Democrats who had expressed support. The Interior Ministry explained that it would accept applications from young foreigners who could provide a secondary school diploma (Hauptschulabschluß) or had lived in Germany for seven years, and who had remigrated to their homeland at age fifteen or older. The application for reentry had to be submitted before their twentieth birthdays or within two years after their departure from West Germany. Successful applicants would receive new permanent residence permits only if they had secured a job or a training position in West Germany and if they could support themselves without social assistance.Footnote 103

The new policy, with some alterations, was codified in the July 1990 revision of the Foreigner Law. In a section titled “Right to Return” (Recht auf Wiederkehr), the Foreigner Law allowed migrants to receive new residence permits if they had legally lived in West Germany for eight years before their departure as a minor, had attended a West German school for at least six of those years, and applied for reentry between their sixteenth and twenty-second birthdays, or within five years of their departure. To assuage concerns about the migrants draining the social welfare system, applicants had to prove that they could finance their stay either through their own employment or through the official registration of a third party who would overtake responsibility for their livelihood for five years. Despite these restrictions, the codified policy was more lenient than originally conceived.Footnote 104

The 1990 revision to the Foreigner Law went one step further, however. The inescapable realization that foreign children who grew up in West Germany were, in fact, members of the national community prompted a reevaluation of the country’s citizenship law altogether. In a section entitled “Facilitated Naturalization” (Erleichterte Einbürgerung), the law enacted two milestone changes. First, it permitted “young foreigners” between the ages of sixteen and twenty-three to naturalize under similar conditions as in the “right to return” provision: if they had continually lived in West Germany for the past eight years and if they had attended school there for six years, four of which at a public school. Second, it granted all foreigners the right to naturalize, as long as they had lived in West Germany regularly for the past fifteen years, could prove that they could provide for themselves and their families without requiring social welfare, and applied for citizenship before December 31, 1995. In both cases, the applicant could not have been sentenced to a crime and had to relinquish their previous citizenship. Although the “right to return” and the “facilitated citizenship” clauses pertained to all foreigners, the target groups were guest workers and their children from countries outside the EEC: the former Yugoslavia, Morocco, Tunisia, and, of course, Turkey.Footnote 105

*****

The hard-fought battle for the “right to return” to West Germany reflected years of both countries’ political, scholarly, and media attention to the plight of allegedly Germanized children who had endured great hardships after returning to a homeland that they did not consider their own. Although the experiences reported in the media were not representative of all guest worker children in Turkey, and although they were often sensationalized, these reports were collectively powerful enough to garner sympathy for the children’s plight. In West Germany, the archetype of the psychologically tormented “return child” was instrumentalized to reinforce preexisting discourses condemning the imagined differences between Turkish migrants’ “authoritarian,” “backward” culture and West Germans’ “free,” “liberal,” and “democratic” society. Herein lies the paradox of West Germans’ attitudes toward these children caught between two countries. Within the boundaries of the West German nation-state, Turkish migrant children seemed to be anything but German. In Turkey, however, the Education Ministry’s last-minute scrambling to “re-Turkify” Germanized children through integration courses underscored that the problem was not insufficient integration into West Germany but rather excessive integration.

The controversial 1990 revisions to the Foreigner Law marked a sea change in German ideas about citizenship. For the first time, most leading West German policymakers, even Kohl’s Christian Democrats, formally acknowledged that guest workers and their children – even if they were Muslim – deserved the opportunity to legally become German. The timing made all the difference. Back in 1981, when Schmidt’s SPD-FDP coalition government had first proposed a citizenship law, the bill was dead on arrival – drowned out by the far more vocal demand “Turks out!” Once the 1983 remigration law passed, and once West Germans increasingly realized that only 15 percent of the Turkish population had decided to leave, they had to come to terms with the reality that Turks – even when provided financial incentives – were there to stay. And, as they observed the children’s struggles to reintegrate into Turkish society from afar, Germans were forced to realize that the children really had integrated into German society, so much so that they identified – or were externally identified – as German. By eroding the rigid boundaries of national identity, Almancı children played a key role in bringing about this milestone revision.

The timing of the citizenship reform and the “right to return” further illuminates West Germany’s efforts to position itself at the end of the Cold War as reunification with socialist East Germany loomed. The Berlin Wall had fallen on November 9, 1989, less than a year before the revised Foreigner Law went into effect, and the public sphere was abuzz with heated debates about how the two Germanies, divided for the past forty-five years, would become one. Policymakers who envisioned the reunified Federal Republic as the natural heir to West German liberal democracy could flaunt their perceived benevolence toward Turkish children. Having “rescued” the children from authoritarianism in Turkey, they could now lay claim to rescuing East Germans from the shackles of socialism. But, by deflecting the children’s abuse onto Turkey and their parents rather than acknowledging Germans’ responsibility for their hardships, this line of thinking obscured the harsher reality: in both the migrants’ perspective and the perspective of their home country, West Germany had failed to uphold its reputation as a bastion of liberal democracy. Despite the 1990 revision to the citizenship law, Turks were still viewed as “foreigners,” continued to endure racism, and fell victim to a resurgence of neo-Nazi violence.