Introduction

Through a focused case study, this article uncovers the intersection of two trends in East Asian studies: the study of local history in China, particularly northern China, and the study of Tangut history, especially after the fall of the Tangut Xia State (1038–1227). This convergence is somewhat expected, as the Tanguts did not disappear with the collapse of their state, but remained a distinct ethnic group in northern China for at least three more centuries. Their continued presence suggests that their unique social organizations endured through the Yuan and well into the Ming dynasty, offering valuable insights for scholars employing the local history paradigm.

Since Robert Hymes,Footnote 1 this paradigm has become essential for studying Middle-Period Chinese history. By focusing on local trends, one can observe how historical developments unfolded in ways that either complement or challenge national dynamics. Local history also provides a crucial framework for the social historian, as local societies offer an ideal entry point into social structures that remain elusive when viewed solely as aspects of national history. However, most studies to date have concentrated on southern China after the year 1000, where plentiful sources have made extensive research possible. Only a few works, such as Tomoyasu Iiyama’s monographs,Footnote 2 have applied the local history model to northern China. Another limitation is that these studies have often centered on local literati, who constituted the social elite after the Northern Song, leaving other social groups largely uninvestigated.

Jinping Wang’s workFootnote 3 represents a significant effort to overcome both of these limitations. Focusing primarily on Shanxi, her research on northern China has highlighted the shifting power dynamics within local society during the Jin–Yuan transition. It has revealed that clerics—first Daoists and then Buddhists—gradually gained influence, whereas local literati declined to a secondary status. Beyond her contribution to changing the research paradigm, her use of epigraphical materials is an important source of methodological inspiration. The scarcity of local historiographical sources in northern China has long posed a major challenge, but Wang’s study has demonstrated that epigraphical materials can provide a crucial alternative. The value of this approach is reinforced by Iiyama’s study of genealogical steles.Footnote 4 Mainly because of northern China’s environmental and climatic conditions, historical records were commonly presented as steles, epitaphs, and the like; these have been better preserved than those in the south, making them a valuable resource for research.

An important question, however, concerns the extent to which Wang’s conclusions can be generalized to other regions of northern China. This issue is particularly pressing because Shanxi has historically been much more religious than the eastern parts of northern China, such as Henan and Hebei. In particular, Dingxiang County, the focus of Wang’s study, is home to Mount Wutai, one of the most significant sites for both Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism after the Yuan dynasty. Given this context, it is hardly surprising that its local society was led by monastics. Therefore, while Wang is confident in her generalization,Footnote 5 it cannot be taken for granted.

This article partly addresses this question; it also uses Buddhism as a key entry point, but situates its case study in Baoding, Hebei. More importantly, it introduces another factor scholars using the local history paradigm must consider: ethnicity.Footnote 6 Previous studies, which predominantly focused on Han Chinese, have rarely examined the roles that Inner Asian ethnic groups played in local societies. However, northern China fell to the Jurchens in 1127; they were later succeeded by the Mongols, so that it remained under non-Han rule for over two centuries. Even after the Ming dynasty was founded, non-Han inhabitants were not simply expelled from their lands. By examining the Tanguts in Baoding and explicitly introducing this ethnic angle, this article aims to offer a fresh perspective.

The primary material for this study—two Tangut dhāraṇī pillars, erected in 1502—is well known in Tangut Studies, as it represents the latest datable Tangut material in existence. The earliest philological examinations of the inscriptions on the two pillars were conducted by a number of Chinese scholars.Footnote 7 The most recent study, by Nie Hongyin,Footnote 8 has corrected some crucial errors in previous scholars’ interpretations and provided insightful new ones regarding the identities of some of the figures the inscriptions document. Numerous other studies, too many to examine here, have explored these pillars over the years. However, most research has focused on the marvel of the fact that a local Tangut community existed in the mid-Ming period, without situating it within the broader framework of northern China’s social history. The religious context of the dhāraṇī inscriptions and the pillars themselves remains somewhat understudied, and there is still no detailed examination of the social status of the many patrons the pillars record.

This article revisits the Tangut pillars to explore the interactions and dynamics of this local community within the conceptual framework of northern China’s local history. The following sections first introduce the key historical information the pillar inscriptions record. The discussion then turns to Tibetan Buddhism’s role in sustaining the Tangut community. It next examines the dhāraṇīs and the pillars themselves, highlighting their significance in Tangut Buddhist practice, then investigates the inscriptions on the pillars which list their patrons’ names. Before concluding, the article analyzes the relationships between the local community’s three central elements—religion, ethnicity, and social structure—to offer a perspective on their interconnections.

The erected, the erector, and those for whom the pillars were erected

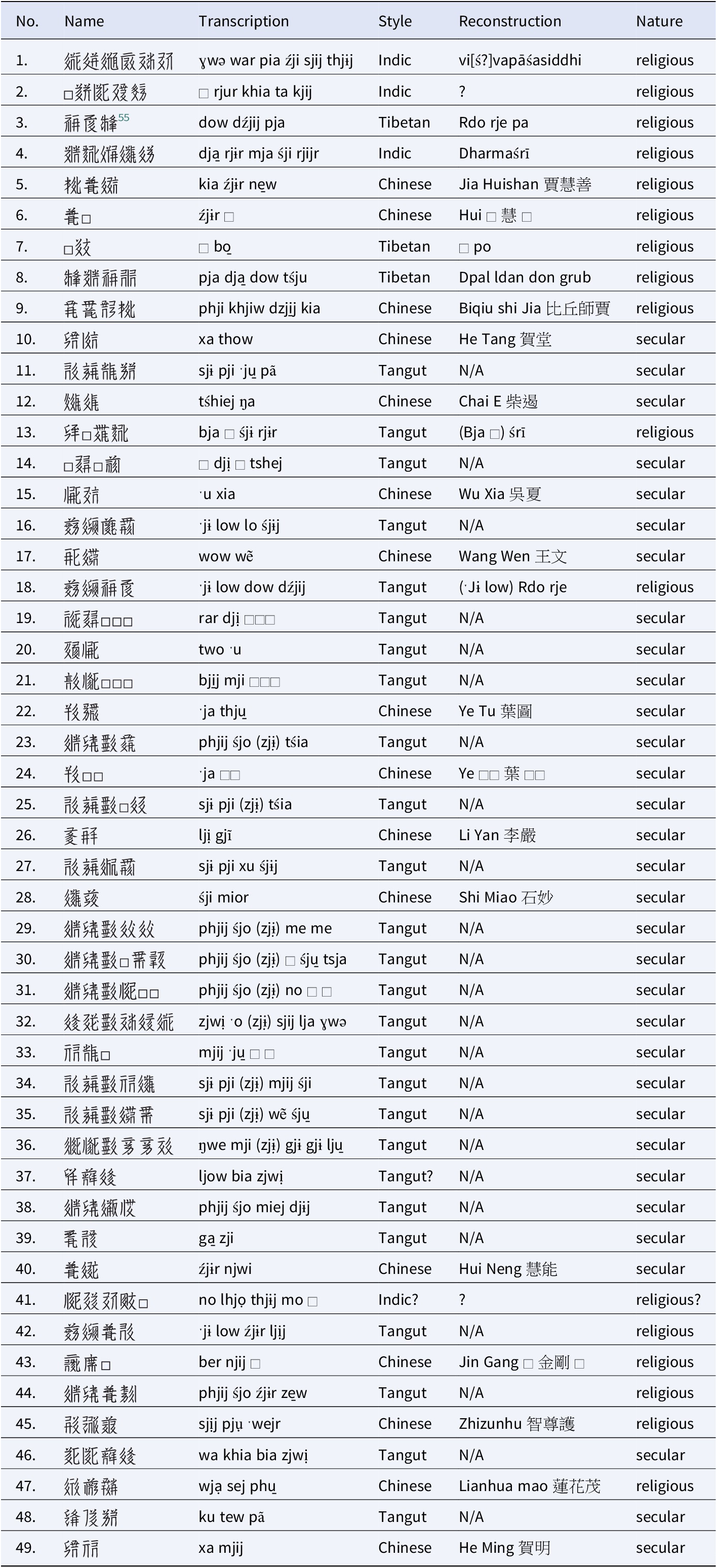

The two pillars were excavated in 1962 in Hanzhuang Township, Baoding City. The archaeological site was reportedly the former location of a monastery with a white stupa, which had been destroyed in the early twentieth century.Footnote 9 Each pillar consists of three octagonal parts: a top cover, a body with eight panels, and a base. Tangut inscriptions are carved onto the panels of each pillar body. Pillar One, standing at 263 cm, is slightly taller than Pillar Two, which measures 228 cm. Both pillars are now housed in Lianchi Park in Baoding (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Tangut Dhāraṇī Pillars (right: Pillar One; left: Pillar Two), 1502. Lianchi Park, Baoding. Photo by Andrew West. September 19, 2017.

The inscription on each pillar consists of three main parts: a commemorative inscription, the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī in a Tangut phonetic transcription, and a list of patrons. For scholars documenting the pillars’ historical background, the commemorative inscriptions are the most significant parts. The commemorative inscription on Pillar One states the following:

In the fourteenth year of the HongzhiFootnote 11 reign of the Great Ming,Footnote 12 at the Xji śji sə monastery, śia mji Pja dja̱ dow dźjij died on the twenty-fourth day of the fourth month. In the fifteenth year, the pillar was erected, and the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī inscription on it was completed. Erector of the pillar: Phjij śjo Tśia śji rjijr dźji̱j.

Pillar Two states the following:

Now, in the fifteenth year of the Hongzhi reign of the Great Ming, at the Xji śji sə monastery, in the graveyard of its stupa courtyard, two li north of the city wall, the phji Footnote 13 khjiw master passed away on the sixth day of the second month. In the ninth month, the pillar was erected, and the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī inscription on it was completed. Erector of the pillar: Phjij śjo Tśia śji rjijr dźji̱j.

On the leftmost side of the first panel of Pillar Two, there is also a line of Chinese script:

大明弘治十五年十月 日, 住持吒失領占建立。

Erected by the abbot Zhashi Lingzhan on a dayFootnote 14 of the tenth month of the fifteenth year of the Hongzhi reign of the Great Ming.

The dates recorded in all three passages are consistent. Both pillars were erected in the fifteenth year of the Hongzhi reign, which corresponds to 1502. The erector is also the same—Phjij śjo Tśia śji rjijr dźji̱j, as the Tangut inscriptions state. Phjij śjo is a well-known Tangut surname, while Tśia śji rjijr dźji̱j is his religious name. Zhashi Lingzhan is evidently the Chinese rendering of this Tangut religious name. The Chinese passage further states that he was an abbot, presumably of the Xji śji sə monastery mentioned in the Tangut inscriptions. Both pillars were dedicated to deceased monastics: Pillar One to a śia mji (Ch. sha mi 沙彌, Skt. śrāmaṇera) named Pja dja̱ dow dźjij, and Pillar Two to a “phji khjiw [Ch. bi qiu 比丘, Skt. bhikṣu] master” whose actual name is not given. Notably, the “stupa courtyard” mentioned in Pillar Two’s inscription appears to correspond exactly with the excavation site of both pillars, in light of reports that a white stupa once stood there.

Xji śji sə Monastery evidently followed the Tibetan Buddhist tradition at least partially. Tśia śji rjijr dźji̱j is a Tangut phonetic rendering of the Tibetan religious name Trashi Rinchen (Tib. Bkra shis rin chen), while Pja dja̱ dow dźjij corresponds to Penden Dorje (Tib. Dpal ldan rdo rje). The white stupa, a distinctive feature of Tibetan Buddhist architecture, became especially prominent after the establishment of the Yuan dynasty, so this detail further reinforces the monastery’s connection to Tibetan Buddhism.

Xingshan Monastery and Tibetan Buddhism

As previous scholars have rightly noted,Footnote 15 Xji śji sə monastery is most plausibly identified with Xingshan Monastery, with xji śji sə being a phonetic transcription of the Chinese xing shan si 興善寺.Footnote 16 The only known historical source providing information about this monastery is a short text titled A Brief Account of the Renovation of Xingshan Monastery” (Chongxiu xingshan si jilue” 重修興善寺記略, henceforth the Account). Written in 1671 by Guo Fen 郭棻 (1622–1690), a Baoding native and a Qing official, it offers valuable insights into the monastery’s history. The full text is as follows:

郡城東南隅之有興善寺者, 不知創自何時。明永樂、宣德間碑皆記重修也。元時碑沒滅不可讀, 厯今三百年矣 。風雨損之, 鳥鼠害之。苔繡香臺, 蠨綱佛座, 瓴甋棟宇, 缺落摧圮。輜衣者流, 望之卻步。寺有棗數株, 異於他種, 每秋熟時, 兒童摘食之。乃有人履迹過此, 則狐兔窟也。嗟乎! 佛教盛于中國已久, 獨此寺衰廢, 一至於此。地為之乎, 人為之乎, 抑時為之乎?

At the southeastern corner of the prefectural city stands Xingshan Monastery, though when it was originally founded is unknown. Stele inscriptions from the Yongle and Xuande eras of the Ming all record its renovations. The Yuan inscriptions have been worn away and are no longer readable—it has been three hundred years since then. Over time, wind and rain have eroded it, birds and rodents have damaged it. Moss has embroidered the incense platform; spiderwebs now veil the Buddha’s throne. The tiles and bricks of its halls have crumbled, with sections collapsing into ruin. Even those with ragged clothes hesitate to step inside. There are several jujube trees in the monastery, different from those found elsewhere. In autumntime, when the fruits ripen, children come to pick and eat them. When people walk by, they see only fox and rabbit dens. Alas! Buddhism has flourished in China for so long, yet this temple alone has declined into such desolation. Is it the deed of the land? Is it an act of the people? Or is it simply the work of time?

我朝定鼎之十年, 郡置防守官兵有分得撥什庫哪杜者, 蒙古人也, 性明敏而好善, 與人謙以和。時四方督兵大率掠也而獲之, 氓也而俘之, 且株連, 且羅織。茹苦者吞聲。公獨潔己而嚴, 其部丁人感德之。公駐節處密邇興善寺, 恆顧而嗟歎焉。遂捐資募眾, 躬率經營。常於烈日塵土中手運木石, 刻期告竣。復延僧清濡為住持, 置園田五畝五分五厘供苾蒭。所修殿三楹、配殿六楹、鐘鼓兩樓、禪堂六間。且高其門以莊觀, 杆其旗以表盛。而丹堊金碧之功, 罔弗備焉。

In the tenth year after the founding of our dynasty, the prefecture stationed defensive troops. Among them there was a Deputy Banner CaptainFootnote 17 named Nadu, a Mongol. He was intelligent, virtuous, and kind, always humble and harmonious in his dealings with others. At that time, most military commanders from all directions pillaged and took captives, seizing commoners as prisoners, implicating others, and fabricating charges. Those who suffered could only endure in silence. Yet, this lord alone remained pure and strict, earning the gratitude of his subordinates. He was stationed near Xingshan Monastery and would often look upon it with sighs of lamentation. Eventually, he donated funds, gathered workers, and personally led the renovation tasks. Under the scorching sun and amidst the dust, he carried timber and stones with his own hands, determined to complete the work by the set deadline. He invited the monk Qingru to serve as the monastery’s abbot and allocated five acres, five tenths, and five hundredths of an acre of land to sustain the monks. What was renovated included three main halls, six auxiliary halls, two bell and drum towers, and six meditation rooms. The entrance gate was elevated to enhance its grandeur, and banners were raised to signify its prosperity. From red paints to golden embellishments, there was no decoration that was not completed.

嗚呼!天下事蓋有地、人與時之相。須數百年而一際者, 有如此舉也。讀明碑所記, 當日重興此寺, 卓錫者則班丹端竹也, 焚修者失![]() 堅參與其徒班丹朵爾只也, 檀越則達官柴武也, 莫非西土人。今哪杜公亦西土人, 相去三百載而重修之, 懓懓乎若有所感而動者, 其非時至則然乎?地之靈也, 佛之靈也, 吾不能不為深感焉。時康熙十年三月。Footnote

18

堅參與其徒班丹朵爾只也, 檀越則達官柴武也, 莫非西土人。今哪杜公亦西土人, 相去三百載而重修之, 懓懓乎若有所感而動者, 其非時至則然乎?地之靈也, 佛之靈也, 吾不能不為深感焉。時康熙十年三月。Footnote

18

Alas! The affairs of the world are characterized by place, people, and time. Some events require centuries before they align and come to fruition—such is the case with this endeavor. Reading the inscriptions on the Ming stele, I find that in days past, when this temple was renovated, the abbot was Bandan duanzhu, while the ones who engaged in daily practices were Shilai jianzan and his disciple Bandan duo’erzhi. The benefactor was High OfficialFootnote 19 Chai Wu—all of them were Inner Asians. Now, Lord Nadu is also an Inner Asian, and after three hundred years, he has renovated it once again. Isn’t it a fact that he was moved by some unseen force because the time had come? This is the spiritual power of the land; this is the spiritual power of the Buddha. I cannot help but be deeply moved. Written in the third month of the tenth year of the Kangxi reign.

None of the steles that Guo saw in the early Qing have survived, making Guo’s second-hand report the only source that allows us a glimpse of the monastery’s history. The last paragraph is particularly relevant to our discussion. The names of the three monastics it mentions—Bandan duanzhu, Shilai jianzan, and Bandan duo’erzhi—are clearly Chinese phonetic transcriptions of Tibetan religious names: Penden Döndrup (Tib. Dpal ldan don grub), Shérap Gyentsen (Tib. Shes rab rgyal mtshan), and Penden Dorje. Nie identifies the Penden Dorje in this account as none other than the deceased Penden Dorje mentioned in Pillar One’s inscription, suggesting that the renovation these three monastics led must have taken place between 1489 and 1501, the year of Penden Dorje’s death.Footnote 20

This identification is further supported by the dates of Chai Wu, the benefactor, who was active in the late fifteenth century (see discussion below). However, one lingering inconsistency remains: Guo Fen explicitly states at the beginning of his Account that “stele inscriptions from the Yongle and Xuande eras of the Ming all record its renovations.” If the renovation the latter part of the text describes occurred in the late fifteenth century, it must have been distinct from the Yongle (1403–1424) and Xuande (1425–1435) renovations. This raises a question about the internal consistency of Guo’s Account, making his narrative appear somewhat unnatural or ambiguous.

Nevertheless, there is little doubt that the Xji śji sə Monastery mentioned in the pillar inscriptions is Xingshan Monastery, which thus links the two sources. By the time Penden Döndrup oversaw its renovation, Xingshan Monastery was already following the Tibetan Buddhist tradition; this connection most likely dates back to the Yuan dynasty, when the monastery was probably first established. The renovations during the Yongle (1403–1424) and Xuande (1425–1435) eras were also not coincidental, as both emperors were known supporters of Tibetan Buddhism. One remaining question concerns the ethnicity of the three monastics mentioned in Guo Fen’s account. While they could certainly be ethnic Tibetans, they could also be Tanguts, as Nie suggests, since Tangut monastics often adopted Tibetan religious names.Footnote 21

Dhāraṇī and Tangut Culture

Tibetan Buddhism began to exert a significant influence on Tangut religious culture in the early twelfth century. However, the earliest datable Tangut translation of a Tibetan Buddhist scripture, the Aparimitāyurjñānasūtra, was published earlier, in 1094. Despite being titled a sūtra, this text primarily consists of dhāraṇīs associated with Buddha Amitāyus. In fact, various dhāraṇī scriptures were among the first to be translated as Tibetan Buddhism gained prominence within the Tangut state;Footnote 22 notable examples include the Pañcarakṣā and the Sitātapatrā. The Uṣṇīṣavijayā, which is inscribed on both pillars, was translated from Tibetan sometime before 1149,Footnote 23 when the Tangut court convened a grand religious assembly to distribute officially printed copies to the public as an act of merit accumulation.

It is no coincidence that the Tangut state decided to prioritize the translation of dhāraṇīs which were available in Tibetan. A defining feature of Tangut Buddhism during the Xia period was the state’s strong involvement in religious affairs. The government was particularly concerned with how Buddhist practices could contribute to state welfare. Reciting dhāraṇīs, in particular, was believed to have powerful transformative effects: good fortune, protection from disasters, extended lifespans, and the warding off of evil spirits. To safeguard both the royal family and the broader population, it was therefore logical for the Tangut state to prioritize the translation and institutionalization of dhāraṇī practices at the state level.

The Tangut state’s inclination toward dhāraṇīs is reflected in the Legal Code of the Tiansheng Era that Revises the Old and Ascertains the New (Ŋwər ljịj kjwi ljij sjiw djɨj kie dzjɨ̱ ![]() ), issued in 1150. One article requires monastics to recite a specific set of Buddhist scriptures, the majority of which were dhāraṇīs. Notably, certain scriptures were designated exclusively either for Tangut and Tibetan monastics or for Chinese monastics. The Uṣṇīṣavijayā was among the few required scriptures for all three ethnic groups, underscoring its significance.Footnote

24 The state’s sponsorship of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā is also evident in its material culture, as Linrothe has shown.Footnote

25 Its fascination with the Uṣṇīṣavijayā persisted into the Yuan period. In 1345 the dhāraṇī was inscribed in six scripts, including Tangut, on the walls of Juyong Pass, a strategically vital section of the Great Wall.

), issued in 1150. One article requires monastics to recite a specific set of Buddhist scriptures, the majority of which were dhāraṇīs. Notably, certain scriptures were designated exclusively either for Tangut and Tibetan monastics or for Chinese monastics. The Uṣṇīṣavijayā was among the few required scriptures for all three ethnic groups, underscoring its significance.Footnote

24 The state’s sponsorship of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā is also evident in its material culture, as Linrothe has shown.Footnote

25 Its fascination with the Uṣṇīṣavijayā persisted into the Yuan period. In 1345 the dhāraṇī was inscribed in six scripts, including Tangut, on the walls of Juyong Pass, a strategically vital section of the Great Wall.

While the Tangut state played a central role in promoting dhāraṇī practices at the national level, they must also have been widespread at local and personal levels within the state, although historical documentation on this aspect is limited. Postscripts in printed dhāraṇīs from the Xia period suggest that certain editions were privately produced rather than government-issued. Some of them also indicate that the dhāraṇīs were so popular that the original print blocks quickly wore out, necessitating new copies.Footnote 26

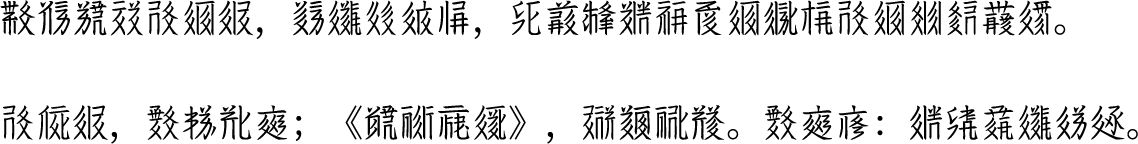

The Uṣṇīṣavijayā was no exception. A Tangut manuscript of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā from Kharakhoto (Or.12380/323; see Figure 2) contains the following postscript:

Now, I have heard the following: The Revered One is compassionate, rescuing all beings of the four births; the excellent Teaching is vast in its merits, spreading across the six realms. Among them, this dhāraṇī is supreme among all secret spells, embodying the protuberance atop the Tathāgata’s head. It was universally spoken by the Buddhas and widely revered by both the manifest and the hidden. If one sees its form or hears its sound, one will be freed from the inferior realms; if one encounters even its shadow or touches a single particle of it, one will attain rebirth in heaven. The highest enlightenment is granted as if bestowed upon one directly, while long life and freedom from illness arise naturally, without the need for cultivation. Recognizing such profound merits, I, Tśhjiw ˑo Sjwɨ̱ tjɨ̣j, a devoted follower, have made a firm resolution to carve the printing blocks and produce these copies with my own hands, distributing them among my brothers. With this virtuous scripture, I humbly offer the following aspirations: May the noble emperor live for ten thousand years, strengthening the foundation of the state. May the ministers live for a thousand years, deepening their loyalty. May all sentient beings throughout the universe attain Buddhahood together. A certain day and month of the seventeenthFootnote 27 year of the TianshengFootnote 28 reign, a ljịj dźjwow Footnote 29 year.

Figure 2. Manuscript of the Tangut Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī, 1165. Kharakhoto. British Library, Or.12380/323.

This date corresponds to the year 1165, not long after the Uṣṇīṣavijayā was translated into Tangut and published by the government. The words of the Tangut author, Tśhjiw ˑo Sjwɨ̱ tjɨ̣j, reflect his deep reverence for this this dhāraṇī and how profoundly impressed he was by its extraordinary efficacy. His printed edition is thus a valuable testament to its widespread acceptance among the Tangut people. Notably, the version under examination is not Tśhjiw ˑo’s original print but a manuscript copy of it. This further attests to the popularity of his private print, which evidently became the version most readily available to the scribe who produced our manuscript.

The Tanguts’ reverence for the Uṣṇīṣavijayā at both local and personal levels is also evident in their art. Two images of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā maṇḍala, painted on wood, were discovered in Kharakhoto (see Figures 3 and 4). Goddess Uṣṇīṣavijayā, the personification of the dhāraṇī, appears at the center of each painting, flanked by her two attendants and surrounded by various deities associated with her. Though somewhat difficult to discern, the complete Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī in Tangut is inscribed in the background. Both paintings depict a benefactor in the lower right-hand corner—one male and one female. Their appearance indicates that they were likely Tangut aristocrats and possibly a husband and wife. Both the artistic style and the Buddhist ritual framework the maṇḍala suggests are clearly Indo-Tibetan rather than Chinese.Footnote 30 This demonstrates how Tibetan Buddhism’s underlying influence helped to sustain Uṣṇīṣavijayā worship within the Tangut state.

Figure 3. Uṣṇīṣavijayā Maṇḍala, ca. late twelfth century. Kharakhoto. Hermitage Museum, XX-2406.

Figure 4. Uṣṇīṣavijayā Maṇḍala, ca. late twelfth century. Kharakhoto. Hermitage Museum, XX-2407.

A distinctive function of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī in Chinese Buddhism is its use in delivering the deceased from the risk of falling into hell. This tradition of employing this dhāraṇī in funerary rites dates back to the early Tang dynasty, following the scripture’s translation into Chinese. The practice of inscribing this dhāraṇī on pillars dedicated to the dead emerged shortly thereafter; the earliest known case is from 732.Footnote 31

While this practice became widespread in medieval China, what remains unclear is how widely the Tanguts embraced this tradition and to what degree they modeled their practices on the Chinese precedent. A woodcut from Kharakhoto depicts a Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī pillar (see Figure 5) whose goddess is iconographically almost identical to that of the maṇḍala paintings shown above. However, whether this pillar was specifically dedicated to the deceased remains uncertain. A more relevant example, discovered in 1977, is a miniature wooden stupa (Figure 6) from a Xia-period tomb in Wuwei, which was then known as Liangzhou. This stupa has four parts: base, body, top cover, and tip. Like the 1502 dhāraṇī pillars, its body consists of eight panels, each 35 cm tall. These panels are inscribed with dhāraṇīs in Pāla script. These inscriptions include several dhāraṇīs from different scriptures, and Wang Rongfei recently identified a mantra at the end of the text: oṃ bhrūṃ svāhā,Footnote 32 which is the distinct inceptive mantra of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī in the Tangut tradition.Footnote 33 The stupa is hollow, and the inside of its top cover features the following inscription (see Figure 7):

故考任西經略司都案劉德仁, 壽六旬有八, 於天慶五年歲次戊午四月十六日亡歿。至天慶七年歲次庚辰□夏十五日興工建緣塔, 至中秋十三日入課訖。Footnote 34

My late father, Liu Deren, who served as Inspector-General of the Western Circuit, lived to the age of sixty-eight and passed away on the sixteenth day of the fourth month in the fifth year of the Tianqing reign, a wuwu year. In the seventh year of the Tianqing reign, a gengchen year, construction of the memorial stupa was initiated on the fifteenth day of the … summer month, and by the thirteenth day of the mid-autumn month, the work was completed.

Figure 5. Woodcut of Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī Pillar, ca. late twelfth century. Kharakhoto. Hermitage Museum, XX-2536.

Figure 6. Wooden stupa, 1200. late twelfth century. Wuwei. Wuwei Museum, G32·002. After Ningxia daxue xixiaxue yanjiu zhongxin et al., Zhongguo cang Xixia wenxian, 260.

Figure 7. Inscription inside the top cover of the wooden stupa.

This inscription reveals that the stupa was dedicated to the tomb’s occupant, Liu Deren, and that he passed away in 1198. While this object is not a stone pillar, its function is identical to that of the 1502 dhāraṇī pillars. Notably, Liu Deren was not a monastic but an Inspector-General (du’an 都案), an official responsible for handling government documents. His name also suggests that he was Han Chinese rather than Tangut. This indicates that, though their promotion was initially a governmental effort, by this time dhāraṇīs in general, and the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī in particular, were widely practiced by different social and ethnic groups within the Tangut state.

In many ways, the 1502 dhāraṇī pillars represent a continuation of Tangut social and religious culture from the Xia period. The local community that produced them, much like the people of the Tangut state, demonstrated reverence for the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī, the Tibetan Buddhist tradition that sustained it, and the funerary practice of erecting pillars. The dhāraṇī text inscribed on the pillars closely follows the 1149 edition, with only minor errors; in terms of textual accuracy, it is of even higher quality than the Uṣṇīṣavijayā inscription on the walls of Juyong Pass,Footnote 35 a project sponsored by the Yuan government. While the Juyong Pass inscription is more elegantly engraved, it contains significantly more textual errors and inappropriate renderings of the dhāraṇī than this local, mid-Ming production. This suggests that local Tangut religious traditions may have had a more stable foundation, and greater resilience against changing political and cultural forces at the national level.

Patrons of the Pillars

But who were the individuals supporting this tradition? The names recorded at the end of each pillar provide an invaluable source of answers. However, interpreting these names presents significant challenges. Many characters are illegible due to wear and erosion. The small size of the patrons’ names compared to the dhāraṇī text further complicates the task, and it is sometimes unclear how characters should be grouped to form a single name. This issue is particularly critical for Tangut names; their structure did not follow a fixed convention, as in other naming systems. To date, only Shi Jinbo has made a comprehensive effort to transcribe all the names,Footnote 36 and even that study did not include a detailed analysis. My renewed attempt to engage with this portion of the pillar inscriptions is therefore far from final or definitive. Nevertheless, it contributes to the ongoing exploration of the social history surrounding these inscriptions.

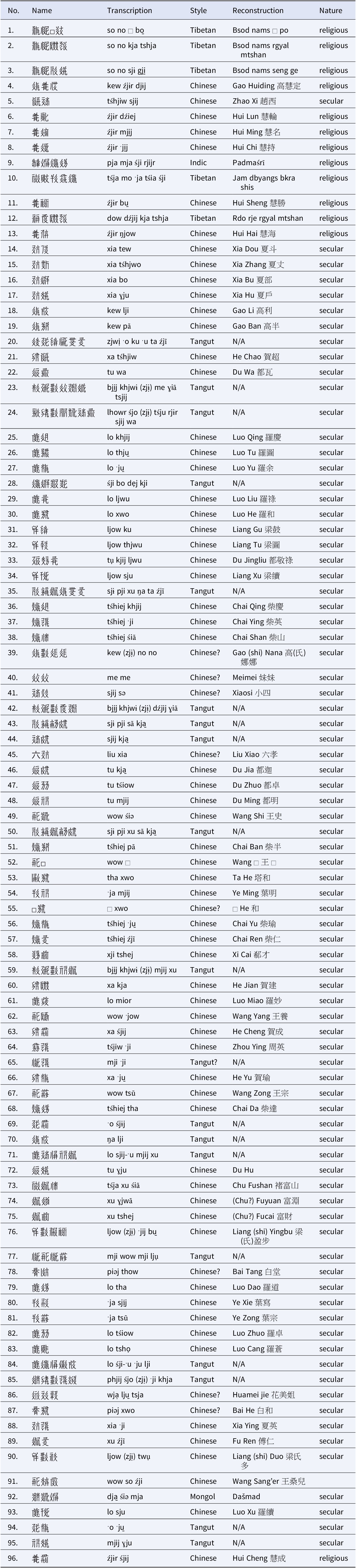

The Appendix provides a complete list of the patrons’ names. Pillar One contains ninety-six names, while Pillar Two has forty-nine. Notably, no name appears on both pillars. This could mean that different patrons were connected to each of the two deceased monastics, but it is hard to imagine that all those who supported the building of Pillar One had no interest in supporting Pillar Two, and vice versa. An alternative possibility, given that both pillars were erected at almost the same time, is that each patron was considered a supporter of both pillars, not just the one on which their name appears.

Each name is analyzed according to a “style,” a classification based entirely on how the name is presented, without implying anything about the individual’s actual ethnicity. For instance, the “Tangut style” generally refers to names that include a Tangut surname.Footnote 37 Similarly, Chinese-style names typically consist of Chinese surnames, phonetically transcribed into Tangut. Tibetan names, such as Sönam Gyentsen (Tib. Bsod nams rgyal mtshan; Pillar One, no. 2), are recognizable due to their phonetic transcription. Additionally, there are several Indic-style names, including Padmaśrī (Pillar One, no. 9), as well as one clearly Mongol name, Dašmad (Pillar One, no. 92). For non-Tangut-style names, I have provided reconstructions to aid in interpretation. This approach does have inherent limitations, particularly for Chinese names, as a single Tangut syllable can correspond to multiple Chinese syllables and various Chinese characters. Despite this, I believe the method remains empirically useful for readers who wish to engage with the names. The final category, “nature,” distinguishes between religious and secular names.

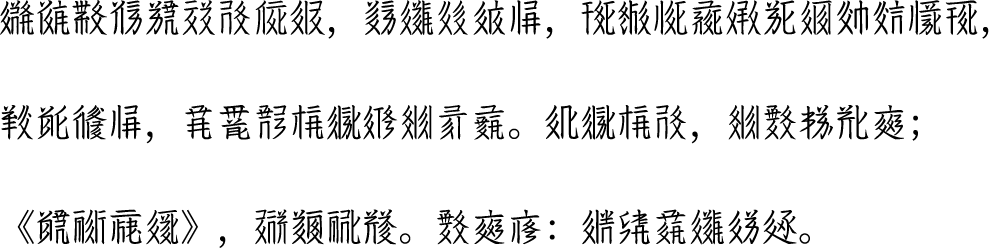

Table 1 presents a statistical breakdown of the names. One category not included in the appendix is gender. The approach to determining gender is necessarily approximate: any surname suffixed with zjɨ̣ ![]() (Ch. shi 氏) is classified as female.

(Ch. shi 氏) is classified as female.

Table 1. Statistical breakdown of the patrons’ names

Since the style of a name does not directly indicate its bearer’s ethnicity, what insights can we still uncover about their ethnic backgrounds? First, it seems highly reasonable to suppose that individuals with Tangut-style names were indeed Tangut, as there is no known historical case of non-Tanguts’ adopting Tangut names.Footnote 38 Conversely, many Tanguts did take Chinese names, a practice already observed during the Xia period. For example, Pillar One contains five Chinese-style names with the surname Liang 梁. Though a Chinese surname, it was also associated with a powerful and aristocratic Tangut family during the Xia period. Similarly, the Luo 羅 family, whose surname appears sixteen times, was influential in the Xia period. While this family may originally have been Chinese, intermarriage with Tangut aristocrats led to their gradual Tangutization. Other Chinese surnames, such as Ye 葉 (five instances) and He 賀 (six instances), were also adopted by Tanguts in the Xia period.

Individuals bearing Chinese-style religious names (thirteen instances) could be either Chinese or Tangut. As previously discussed, some Tanguts also adopted Tibetan religious names. Likewise, the one recorded Mongol name may have belonged to a Tangut who adopted a Mongol name, a common practice during the Yuan period. Taking all these factors into account, the percentage of ethnic Tanguts among the pillar inscriptions’ name-bearers is likely close to fifty percent.

The presence of four Indic names does not necessarily indicate that all these individuals originated from the Indic world. However, at least one seems to have had a direct connection: the first figure listed on Pillar Two, who is explicitly identified with the title “Indic master from the Western Heaven” (![]() ). Some of these figures may have been Uyghurs, who often adopted Indic religious names. It would have been unusual for a Chinese individual of this period to take a Tibetan name, even in a monastic context. However, Mongols, like Tanguts, may have adopted Tibetan names as well. At the other extreme, it is difficult to believe that no ethnic Tibetans were present at all. As the previous section demonstrated, Xingshan Monastery clearly adhered to Tibetan Buddhist traditions, and the presence of at least one Indic master shows that the monastic community did not have to be entirely local. Hence, it is reasonable to assume the presence of some ethnic Tibetans.

). Some of these figures may have been Uyghurs, who often adopted Indic religious names. It would have been unusual for a Chinese individual of this period to take a Tibetan name, even in a monastic context. However, Mongols, like Tanguts, may have adopted Tibetan names as well. At the other extreme, it is difficult to believe that no ethnic Tibetans were present at all. As the previous section demonstrated, Xingshan Monastery clearly adhered to Tibetan Buddhist traditions, and the presence of at least one Indic master shows that the monastic community did not have to be entirely local. Hence, it is reasonable to assume the presence of some ethnic Tibetans.

A religious name does not necessarily indicate a monastic identity. For example, the name ˑJɨ low dow dźjij (Pillar Two, no. 18) is religious in nature, as dow dźjij is a phonetic transcription of the Tibetan rdo rje (“vajra”). However, a monastic’s religious name usually has more than one semantic component. Since ˑJɨ low is a Tangut surname, this individual may have been a layperson whose given name was religious in form but not an indication of monastic status. Nevertheless, there are strong reasons to believe that most individuals with religious names were indeed monastics. The majority of these names are grouped together at the beginning of the lists, suggesting a hierarchical ordering that reflects their superior monastic status in a religious context. Pillar Two features another cluster of religious names at the end, possibly a later addition, yet still arranged as a distinct group. In contrast, ˑJɨ low dow dźjij appears as a single religious name within a sequence of secular names, further supporting the interpretation that this individual was a layperson.

It is difficult to identify female names within the secular category, apart from those containing zjɨ̣. Women who entered the monastic order under Chinese-style names also cannot be identified with certainty. Female names are predominantly Tangut in style, with only three exceptions. Two of these include the surname Liang (Pillar One, nos. 76 and 90), while the other (Pillar One, no. 39) is of uncertain reconstruction, making it unclear whether it was a Chinese name. The presence of female Tangut names in this context is not surprising, as women were already active participants in religious activities during the Xia period. Several prominent women, such as Empress Dowager Liang (d. 1099), were known for their strong patronage of religious assemblies.Footnote 39 Buddhist paintings from the Xia period often depict female worshippers (see Figure 4), further attesting to their involvement in religious life.

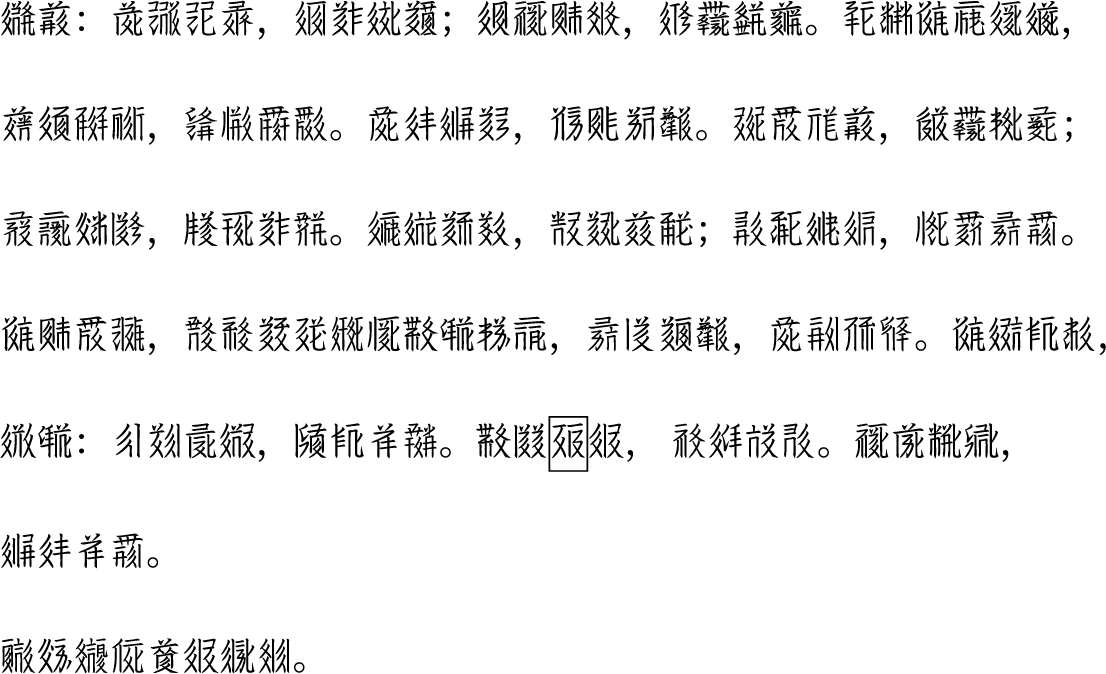

One significant piece of information about the patrons comes from the lists’ use of official titles, affixed to personal names. On Pillar Two, three Tangut names—ˑJɨ low lo śjɨj (no. 16), Bji̱j mji □□□ (no. 21), and Sjɨ pji xu śjɨj (no. 27)—are preceded by a title, inscribed in a relatively larger size: źju lo thej xu ![]() (see Figure 8, upper circle). This title is a phonetic transcription of the Chinese ronglu dafu 榮祿大夫, “Grand Master of Honor and Emolument,” an honorary title (Ch. sanguan 散官) of the junior first rank. Below these names, another title appears: tu tśjĩ xwej

(see Figure 8, upper circle). This title is a phonetic transcription of the Chinese ronglu dafu 榮祿大夫, “Grand Master of Honor and Emolument,” an honorary title (Ch. sanguan 散官) of the junior first rank. Below these names, another title appears: tu tśjĩ xwej ![]() , (Figure 8, lower circle), a phonetic transcription of the Chinese du zhihui 都指揮, “Commandant.” This was a functional official title (Ch. zhiguan 職官), granted to head officers of the Regional Military Command Office (Ch. du zhihuishi si 都指揮使司)—a second- or senior third-rank military position. This suggests that these three individuals simultaneously held both an honorary title and an actual official title,Footnote

40 and that they served at a Regional Military Command Office—possibly that of Daning 大寧, whose headquarters at that time were in Baoding.

, (Figure 8, lower circle), a phonetic transcription of the Chinese du zhihui 都指揮, “Commandant.” This was a functional official title (Ch. zhiguan 職官), granted to head officers of the Regional Military Command Office (Ch. du zhihuishi si 都指揮使司)—a second- or senior third-rank military position. This suggests that these three individuals simultaneously held both an honorary title and an actual official title,Footnote

40 and that they served at a Regional Military Command Office—possibly that of Daning 大寧, whose headquarters at that time were in Baoding.

Figure 8. Rubbing of Pillar Two (Detail). After Du and Deng, Dangxiang yu Xixia beike tiji, 2:411.

A Tangut’s holding a high-ranking military position was not unprecedented in Ming history. A Tangut version of the Scripture of the High King Avalokiteśvara (Ch. Gaowang Guanshiyin jing 高王觀世音經), likely printed in 1432,Footnote

41 records its principal patron as Zjwị ˑo ˑJi-r[jɨr] kja̱ tha-ˑjij ![]() . His surname clearly identifies him as Tangut, yet his given name, which can be reconstructed as Irgetei,Footnote

42 is Mongol, reflecting a partially Mongolized identity under the influence of the previous dynasty. His name is followed by the title tu tu

. His surname clearly identifies him as Tangut, yet his given name, which can be reconstructed as Irgetei,Footnote

42 is Mongol, reflecting a partially Mongolized identity under the influence of the previous dynasty. His name is followed by the title tu tu ![]() , a phonetic transcription of the Chinese du du 都督, “Military Commissioner.” This was an even higher-ranking title than Commandant, corresponding to a military position of the first or senior second rank. His status within the Ming military hierarchy is consistent with that of the Commandants who supported the 1502 dhāraṇī pillars.

, a phonetic transcription of the Chinese du du 都督, “Military Commissioner.” This was an even higher-ranking title than Commandant, corresponding to a military position of the first or senior second rank. His status within the Ming military hierarchy is consistent with that of the Commandants who supported the 1502 dhāraṇī pillars.

Pillar One provides another important clue: the title tśjĩ xwej, which straddles two lines of names. It corresponds to the Chinese zhihui 指挥, “Garrison Commander” (see Figure 9). A Garrison Commander was one of the head officers of a garrison (Ch. wei 衛)—the largest military unit under a Regional Military Command Office. However, it remains unclear to which specific names this title applies. Since it is positioned precisely between two lines of names, it seems likely that the four names below it (nos. 64, 65, 78, and 79) should be prefixed with this title—or at the very least, the top two names (nos. 64 and 78). I have been able to identify the individual who bore the first name, Tśjiw ˑji. In the register of the Baoding Left Garrison (Baoding zuo wei 保定左衛), which was under the jurisdiction of the Regional Military Command Office of Daning, the following record appears:

周英, 昆山縣人。曾祖周阿孫吳元年充軍, 老疾。祖周成補役, 三十二年陞小旗, 滄州陞總旗。三十四年滹沱河等虜, 陞實授百戶, 三十五年方順橋陞副千戶, 病故。父周![]() 優給, 宣德貳年襲職, 正統十四年西直門外并易州五郎诃節次殺賊有功, 景泰元年以西直門外功陞正千戶, 易州五郎河功陞指揮僉事, 老疾。英係嫡長男, 成化九年替本衛指揮僉事。十七年, 欽與世襲。Footnote

43

優給, 宣德貳年襲職, 正統十四年西直門外并易州五郎诃節次殺賊有功, 景泰元年以西直門外功陞正千戶, 易州五郎河功陞指揮僉事, 老疾。英係嫡長男, 成化九年替本衛指揮僉事。十七年, 欽與世襲。Footnote

43

Zhou Ying 周英 was a native of Kunshan County. His great-grandfather, Zhou Asun 周阿孫, was conscripted into military service in the first year of Wu (1367), but later suffered from illness due to old age. Zhou Ying’s grandfather, Zhou Cheng 周成, served in place of his father and was promoted to Junior Banner Officer (Ch. xiaoqi 小旗) in the thirty-second year (1399). He was later promoted to Senior Banner Officer (Ch. zongqi 總旗) in Cangzhou 滄州. In the thirty-fourth year (1400), during military engagements along the Hutuo he 滹沱河, he was promoted to the official rank of Hundred-Household Commander (Ch. baihu 百戶). In the thirty-fifth year (1401), after the battle at Fangshun qiao 方順橋, he was further promoted to Deputy Thousand-Household Commander (Ch. fu qianhu 副千戶), but later died of illness. Zhou Ying’s father, Zhou Yao 周![]() , was granted preferential treatment due to his family’s service. In the second year of Xuande (1426), he inherited his father’s position. In the fourteenth year of Zhengtong (1449), he demonstrated merit in battles outside Xizhi men 西直門 and in the engagement at Wulang he 五郎河 in Yizhou 易州, killing enemy forces. In the first year of Jingtai (1450), for his merits outside Xizhi men, he was promoted to Thousand-Household Commander (Ch. zheng qianhu 正千戶), and for his merits in Wulang he, Yizhou, he was further promoted to Assistant Garrison Commander (Ch. zhihui qianshi 指揮僉事). He later suffered from illness due to old age. Zhou Ying, as the eldest legitimate son, replaced his father as Assistant Garrison Commander of this garrison in the ninth year of Chenghua (1473). In the seventeenth year (1481), he was granted hereditary succession by imperial decree.

, was granted preferential treatment due to his family’s service. In the second year of Xuande (1426), he inherited his father’s position. In the fourteenth year of Zhengtong (1449), he demonstrated merit in battles outside Xizhi men 西直門 and in the engagement at Wulang he 五郎河 in Yizhou 易州, killing enemy forces. In the first year of Jingtai (1450), for his merits outside Xizhi men, he was promoted to Thousand-Household Commander (Ch. zheng qianhu 正千戶), and for his merits in Wulang he, Yizhou, he was further promoted to Assistant Garrison Commander (Ch. zhihui qianshi 指揮僉事). He later suffered from illness due to old age. Zhou Ying, as the eldest legitimate son, replaced his father as Assistant Garrison Commander of this garrison in the ninth year of Chenghua (1473). In the seventeenth year (1481), he was granted hereditary succession by imperial decree.

Figure 9. Rubbing of Pillar One (Detail). After Du and Deng, Dangxiang yu Xixia beike tiji, 2:413.

On the same page, there is also the following record:

弘治十七年九月——周堂, 昆山縣人, 係保定左衛故世襲指揮僉事周英嫡長男。Footnote 44

The ninth month of the seventeenth year of Hongzhi (1504)—Zhou Tang 周堂, a native of Kunshan County, was the eldest legitimate son of Zhou Ying, the late hereditary Assistant Garrison Commander of Baoding Left Garrison.

It seems highly reasonable to identify Tśjiw ˑji with Zhou Ying—and not merely due to their similar pronunciations.Footnote 45 Zhou Ying was appointed Assistant Garrison Commander in 1473, and was stationed in Baoding. He likely passed away in 1504, at which point his son, Zhou Tang 周堂, inherited his position. These details align perfectly with the information recorded on the 1502 dhāraṇī pillars.

The Zhou family was not originally from Baoding. Their ancestor, Zhou Asun, began his military service in southeastern China, as a soldier in Zhu Yuanzhang’s army. However, by Zhou Cheng’s time the family was already stationed at the Regional Military Command Office of Daning, whose headquarters were then located not in Baoding but outside the Great Wall, in present-day Inner Mongolia. Zhou Cheng apparently joined Zhu Di’s army during the Jingnan Campaign, and was promoted as a result of its victories. In 1403, following Zhu Di’s ascension as the Yongle Emperor, the Command Office was relocated to Baoding; this was likely the beginning of the Zhou family’s history in the prefecture. Zhou Yao earned significant military merit in 1449 during the defense against the Oirat Mongols, and was ultimately promoted to Assistant Garrison Commander. He did not inherit his father’s position immediately after his father’s death; this suggests that before taking office he still had to reach adulthood, normally sixteen years of age. This means Zhou Yao likely came of age in 1426, which in turn suggests that he was already a Baoding native, possibly born around 1411. Zhou Ying, then, already represented the second generation of the Baoding-based Zhou family.

Unlike the head officers in a Regional Military Command Office, who obtained their positions by appointment, the head officers in a garrison could inherit their posts. These positions were passed down within military households, as the case of the Zhou family exemplifies. In particular, since the Zhou family stood with Zhu Di in the Jingnan Campaign and served meritoriously, they were regarded thereafter as the “New Officials” (Ch. xin guan 新官) within the garrison system,Footnote 46 entitling them to a rich hereditary emolument. This further solidified their continuing local presence. In fact, their position of Assistant Garrison Commander in Baoding Left Garrison remained within the Zhou family until the death of Zhou Shangde 周尚德 in 1636. His son, Zhou Zhizhen 周之禎, was then only four years old but continued to receive the emolument until 1647, even after the Ming dynasty fell. This system of fixed stationing and hereditary succession made military households like the Zhou family a significant social force in areas such as Baoding, where multiple garrisons were concentrated.

A similar lineage is that of the Chai family, whose members appear eight times in total across both of the 1502 dhāraṇī pillars. Xu Cheng has examined the Chai family in Baoding and identified Chai Wu, the benefactor who helped renovate Xingshan Monastery (discussed above), in the register of Baoding Left Garrison.Footnote 47 Chai Wu became Deputy Garrison Commander (Ch. zhihui tongzhi 指揮同知) in 1476, inheriting the position from his nephew, who had died prematurely. Chai Wu passed away in 1501, just before the construction of the dhāraṇī pillars, which explains the absence of his name from the list of patrons. His career closely overlapped with Zhou Ying’s; the two served together as colleagues and head officers in the Baoding Left Garrison for nearly three decades.

Unlike the Zhou family, the Chai family was granted the additional title “High Official.” However, the Chinese term da guan 達官 could also mean “Tatar Official” (鞑官), a title frequently bestowed upon nomads—primarily Mongols—who became officers of the Ming military. Indeed, according to the military register, the Chai family originated from Ta Tan 塔灘; this geographical designation generally refers to the northern part of the Hetao region. The family’s early patriarchs retained Mongol names as part of their given names, further indicating their nomadic ancestry. Therefore, the Chai family members listed on the dhāraṇī pillars were most likely from the same lineage as Chai Wu, and their Mongol heritage remained an integral part of their identity.

Now, let us piece the puzzle together and reconstruct a picture of the local community that sustained Xingshan Monastery’s activities in Baoding. This was a multiethnic community: approximately half Tanguts, some Chinese, a few Mongols, several Tibetans and Indic figures, and possibly one or two Uyghurs. Monastics made up only about a fifth of the population, but within this religious setting they held a higher status. Most laywomen were Tanguts, while all men with official titles were military officers; these included Tanguts, Chinese, and Mongols. Some of these officers belonged to hereditary military households, permanently stationed in Baoding due to their garrison assignments. This fixed military presence ensured their long-lasting local influence, shaping both military and religious affairs in the region.

Religion, ethnicity, and social structure

The existence of local Tangut communities in the post-Xia era is well-known among scholars. A typical example is the Yang family of Puyang, which has been widely studied by researchers such as Iiyama.Footnote 48 However, these Tangut-descended communities largely followed the broader social trends of Chinese society, particularly the rise of localized literati and gentry. Over time many of them, including the Yang family, immersed themselves in Chinese literary culture, sidelining their Tangut traditions. What makes the Baoding Tangut community unique is that they not only continued to use the Tangut language and script until the early sixteenth century, but also preserved the religious traditions that had developed during the Xia period. This is most evident in two distinct features of Tangut Buddhist practice: their worship of the Uṣṇīṣavijayā dhāraṇī and their reverence for Tibetan Buddhism. While it remains possible that Chinese literary traditions also existed within their community, their continuation of Tangut Buddhist practices undoubtedly played a key role in preserving their distinct cultural identity.

The local Buddhist tradition clearly influenced non-Tanguts as well. Although the Zhou family was Chinese, not Tangut, during their long residency in the Baoding area they had been acculturated into Tangut Buddhist traditions. The Chai family’s support for Xingshan Monastery is even less surprising, given their Mongol ancestry. Since the Mongols had inherited a strong interest in Tibetan Buddhism from the Tanguts as early as Köden’s time,Footnote 49 the Chai family’s religious alignment with the local Tangut community was quite natural. Xu suggested that the Chai family may have originally been Tanguts, and later became Mongolized during the Yuan dynasty.Footnote 50 In that case, the alignment would be even more reasonable.

While continuing their religious traditions played a crucial role in preserving their distinct ethnic identity, the Tanguts also had pragmatic motivations for maintaining it. Unlike the Kitans and Jurchens, the Tanguts were classified as Semu 色目 people under the Yuan dynasty; this placed them just below the Mongols in the ethnic hierarchy, so preserving a strong Tangut cultural identity helped them to retain privileges under Mongol rule. These motivations did not suddenly disappear once the Ming dynasty was established. During the Yuan period, many Tanguts, including the Yang family of Puyang, had served in the Mongol army and held high-ranking military positions. As a result, their military identity had become closely intertwined with their ethnic identity. As David Robinson has noted, the early Ming military system inherited many traditions from the Yuan,Footnote 51 and consequently numerous recruits were former Yuan officers. This policy is reflected in an imperial decree which Zhu Yuanzhang issued in 1368: “Since the Mongols and Semu people have settled in my land, they are my children. Those with talent shall be equally appointed to office.”Footnote 52 The opportunity for a military career within the Ming government helped sustain the Tanguts’ military identity, even as the civil examination system was revived.

It is therefore unsurprising that all the post-Xia Tangut officials discussed in this article were military officials. The military tradition provided strong resistance against assimilation into literary culture, and the institutions of military households and hereditary military posts, which persisted through both the Yuan and the Ming, further reinforced this identity. The military household system and the garrison structure also played a key role in integrating these military individuals into Baoding’s social milieu, contributing significantly to the formation of a local society composed of distinct ethnic minority groups. Military officials served as colleagues within the same garrison unit, and this fostered their professional and institutional ties; their households too were often situated in close proximity, further strengthening social bonds. These factors enabled military families to develop long-lasting local networks, shaping the ethnic and social landscape of their communities.

These social bonds fostered the cultivation of a shared religious culture. Xingshan Monastery clearly did not depend on a single family, but on the local community as a whole. Whereas the monastics of Mt. Wutai during the Yuan dynasty derived much of their power directly from imperial sponsorship, the monastic–lay relationship in Baoding was entirely shaped by local dynamics. This ensured that Baoding’s religious traditions were sustained through local support networks rather than state patronage. Although this Buddhist tradition had eventually died out by the time of Guo Fen in the early Qing, his observations reveal an important historical reality: Inner Asians and their cultural influence played a critical role in initiating, maintaining, and reviving local Buddhist traditions, which were integral to their Inner Asian identity.

Conclusion

This article has explored the intricate dynamics of the local community that supported the Tangut dhāraṇī pillars which were erected in 1502. In this context, ethnic identity emerges as a key nexus, weaving together the many aspects of the local socio-religious landscape. The distinct Tangut identity was a unifying framework that allowed Buddhist and military traditions to intersect and shape local developments. While the Tanguts were an absolute ethnic minority, numerically insignificant within the broader trajectory of Chinese social history after 1227, these Tangut communities, distinguished by their unique traditions, were like pinpoints on the map of northern China—small but significant. From the perspective of the local history paradigm, such groups were not marginal but crucial, offering valuable insights into regional dynamics and cultural continuity.

Ethnic identity in post-Jin northern China was, of course, not limited to the Tanguts. The region was a hub of diverse ethnic groups, each contributing to its cultural landscape. As this study has briefly highlighted, many Mongols also developed distinct local cultures. Another group deserving attention is the Huihui 回回, whose presence, as Zhao Shiyu has noted, was particularly significant within the garrison system.Footnote 53 Much as the Tanguts preserved their Buddhism, Muslims too must have worked to preserve their religious traditions within the military and social structures of the time. Interactions between these minority groups and the Han Chinese majority also merit investigation; Baoding provides the compelling example of how the Zhou family became deeply involved in Tangut cultural traditions despite being ethnically Chinese, likely due to the military background they shared with local Tangut households. The Tangut community this article has examined is only one of those which endured after the fall of the Tangut state; Nie has briefly introduced other Tangut communities in Hebei,Footnote 54 all of which warrant further investigation from a local history perspective.

This article has uncovered an intersection between the local history paradigm in Chinese historiography and Tangut studies, but it is only a starting point. With the ongoing development of Tangut scholarship and the continued discovery of new Tangut materials, more intersections of this sort are certain to emerge. The 275 years from 1227 to 1502 undoubtedly hold many fascinating moments like the one revealed by the Baoding dhāraṇī pillars, and most are still waiting to be explored.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to Andrew West, who generously shared with me his experiences from his field trips to the Baoding pillars, and to whom I had promised to send the published article. It is with great sadness that he passed away before it could be published. This article is dedicated to his memory, in recognition of his being one of the few scholars in the West who actively engaged in Tangut Studies and made outstanding contributions to the field.

Competing interests

The author declares none

Appendix: Names on the Dhāraṇī Pillars

Pillar One

Pillar Two